Two early 20th century Korean women breastfeeding their babies while working

The history and culture of breastfeeding traces changing social, medical and legal attitudes to breastfeeding, the act of feeding a child breast milk directly from breast to mouth. Breastfeeding may be performed by the infant's mother or by a surrogate, typically called a wet nurse.

Breastfeeding is the natural means by which a baby receives

nourishment. In most societies women usually nurse their own babies,

this being the most natural, convenient and cost effective method of

feeding a baby. However there are situations when a mother cannot suckle

her own baby. For example, she may have died, become unwell or

otherwise cannot produce breast milk. Before the availability of infant formula, in those situations, unless a wet nurse was found promptly, the baby might die, and infant mortality

rates were high. Wet nurses were a normal part of the social order,

though social attitudes to wet nursing varied, as well as to the social

status of the wet nurse. Breastfeeding itself began to be seen as

common; too common to be done by royalty, even in ancient societies, and

wet nurses were employed to breastfeed the children of royal families.

This attitude extended over time, particularly in western Europe, where

babies of noble women

were often nursed by wet nurses. Lower-class women breastfed their

infants and used a wet nurse only if they were unable to feed their own

infant.

Attempts were made in 15th-century Europe to use cow or goat

milk, but these attempts were not successful. In the 18th century, flour

or cereal mixed with broth were introduced as substitutes for

breastfeeding, but this was also unsuccessful. Improved infant formulas appeared in the mid-19th century, providing an alternative to wet nursing, and even breastfeeding itself.

During the early 20th century, breastfeeding started to be viewed

negatively, especially in Canada and the United States, where it was

regarded as a low class and uncultured practice. The use of infant formulas increased, which accelerated after World War II.

From the 1960s onwards, breastfeeding experienced a revival which

continued into the 2000s, though negative attitudes towards

breastfeeding were still entrenched up to 1990s.

Early history

Old-Babylonian plaque of a sitting woman breastfeeding her infant, from Southern Mesopotamia, Iraq

Moche ceramic vessel showing a woman breastfeeding. Larco Museum Collection. Lima-Perú

Princess Sobeknakht Suckling a Prince, ca. 1700-after 1630 B.C.E Brooklyn Museum

In the Egyptian, Greek and Roman empires,

women usually fed only their own children. However, breastfeeding

began to be seen as something too common to be done by royalty, and wet nurses

were employed to breastfeed the children of the royal families. This

was extended over the ages, particularly in western Europe, where noble women often made use of wet nurses. The Moche artisans of Peru (1–800 A.D.) represented women breastfeeding their children in ceramic vessels.

Shared breastfeeding is still practised in many developing countries when mothers need help to feed their children.

Japan

Traditionally, Japanese women gave birth at home and breastfed with the help of breast massage. Weaning was often late, with breastfeeding in rare cases continuing until early adolescence. After World War II Western medicine was taken to Japan and the women began giving birth in hospitals, where the baby was usually taken to the nursery and given formula milk.

In 1974 a new breastfeeding promotional campaign by the government

helped to boost the awareness of its benefits and its prevalence has

sharply increased. Japan became the first developed country to have a baby-friendly hospital, and as of 2006 has another 24 such facilities.

Islam

In the Qur'an it is stated that a child should be breastfed if both parents agree:

Mothers may breastfeed their children two complete years for whoever wishes to complete the nursing ... And if you wish to have your children nursed by a substitute, there is no blame upon you as long as you give payment according to what is acceptable. (parts of Surat al-Baqarah 2:233) ... and his gestation and weaning [period] is thirty months ... (part of Surat al-Ahqaf 46:15)

Islam has recommended breastfeeding for two years till 30 months,

either by the mother or a wet nurse. Even in pre-Islamic Arabia

children were breastfed, commonly by wet nurses.

18th century

Painting of a woman breastfeeding at home, Netherlands

In the 18th century male medical practitioners started to work on the

areas of pregnancy, birth and babies, areas traditionally dominated by

women. Also in the 18th century the emerging natural sciences argued that women should stay at home to nurse and raise their children, like animals also do.

Governments in Europe started to worry about the decline of the

workforce because of the high mortality rates among newborns. Wet

nursing was considered one of the main problems. Campaigns were launched

against the custom among the higher class to use a wet nurse. Women

were advised or even forced by law to nurse their own children. The biologist and physician Linnaeus, the English doctor Cadogan,

Rousseau, and the midwife Anel le Rebours described in their writings

the advantages and necessity of women breastfeeding their own children

and discouraged the practice of wet nursing. Sir Hans Sloane

noted the value of breast-feeding in reducing infant mortality in 1748.

His Chelsea manor which was later converted to a botanic garden was

visited by Carl Linnaeus in 1736.

In 1752 Linnaeus wrote a pamphlet against the use of wet nurses.

Linnaeus considered this against the law of nature. A baby not nursed by

the mother was deprived of the laxative colostrum. Linnaeus thought

that the lower class wet nurse ate too much fat, drank alcohol and had

contagious (venereal) diseases, therefore producing lethal milk.

Cover of Linnaeus' Nutrix Noverca (1752)

Mother's milk was considered a miracle fluid which could cure people

and give wisdom. The mythical figure Philosophia-Sapientia, the

personification of wisdom, suckled philosophers at her breast and by

this way they absorbed wisdom and moral virtue.

On the other hand, lactation was what connected humans with animals.

Linnaeus – who classified the realm of animals – did not by accident

rename the category 'quadrupedia' (four footed) in 'mammalia' (mammals).

With this act he made the lactating female breast the icon of this

class of animals in which humans were classified.

19th century

Historian Rima D. Apple writes in her book Mothers and Medicine. A Social History of Infant Feeding, 1890–1950 that in the United States of America most babies got breastmilk.

Dutch historian Van Eekelen researched the small amount of available

evidence of breastfeeding practices in The Netherlands. Around 1860 in

the Dutch province of Zeeland about 67% of babies were nursed, but there

were big differences within the region.

Women were obliged to nurse their babies: “Every mother ought to nurse

her own child, if she is fit to do it (...) no woman is fit to have a

child who is not fit to nurse it.”

Mother's milk was considered best for babies, but the quality of

the breastmilk was found to be varied. The quality of breastmilk was

considered good only if the mother had a good diet, had physical

exercise and was mentally in balance.

In Europe (especially in France) and less in the USA it was a practice

among the higher and middle class to hire a wet nurse. If it was too

difficult to find a wet nurse, people used formula to feed their babies,

but this was considered very dangerous for the health and life of the

baby.

Decline and resurgence in the 20th and 21st centuries

Breastfeeding in the Western world declined significantly from the late 1800s to the 1960s.

By the 1950s, the predominant attitude to breastfeeding was that it

was something practiced by the uneducated and those of lower classes.

The practice was considered old-fashioned and "a little disgusting" for

those who could not afford infant formula and discouraged by medical

practitioners and media of the time. Letters and editorials to Chatelaine from 1945 to as late as 1995 regarding breastfeeding were predominantly negative.

However, since the middle 1960s there has been a steady resurgence in

the practice of breastfeeding in Canada and the US, especially among

more educated, affluent women.

In 2018, Transgender Health reported that a transgender

woman in the United States breastfed her adopted baby; this was the

first known case of a transgender woman breastfeeding.

Canada

A 1994

Canadian government health survey found that 73% of Canadian mothers

initiated breastfeeding, up from 38% in 1963. It has been speculated

that the gap between breastfeeding generations in Canada contributes to

the lack of success of those who do attempt it: new parents cannot look

to older family members for help with breastfeeding since they are also

ignorant on the topic.

Indigenous women in Canada are particularly affected by their loss of

traditional breastfeeding knowledge, which taught mothers to breastfeed

for at least 2 years and up to 4-5 years after birth, as a result of

settler colonialism; Indigenous mothers now initiate breastfeeding and

exclusively breastfeed for at least 6 months at significantly lower

rates than non-Indigenous mothers in Canada. Western Canadians are more likely to breastfeed; just 53% of Atlantic

province mothers breastfeed, compared to 87% in British Columbia. More

than 90% of women surveyed said they breastfeed because it provides more

benefits for the baby than does formula. Of women who did not

breastfeed, 40% said formula feeding was easier (the most prevalent

answer). Women who were older, more educated, had higher income, and

were married were the most likely to breastfeed. Immigrant women were

also more likely to breastfeed. About 40% of mothers who breastfeed do

so for less than three months. Women were most likely to discontinue

breastfeeding if they perceived themselves to have insufficient milk.

However, among women who breastfed for more than three months, returning

to work or a previous decision to stop at that time were the top

reasons.

A 2003 La Leche League International study found that 72% of Canadian mothers initiate breastfeeding and that 31% continue to do so past four to five months.

A 1996 article in the Canadian Journal of Public Health found

that, in Vancouver, 82.9% of mothers initiated breastfeeding, but that

this differed by Caucasian (91.6%) and non-Caucasian (56.8%) women.

Just 18.2% of mothers breastfeed at nine months; breastfeeding

practices were significantly associated with the mothers' marital

status, education and family income.

Cuba

Since 1940, Cuba's

constitution has contained a provision officially recognising and

supporting breastfeeding. Article 68 of the 1975 constitution reads, in

part:

During the six weeks immediately preceding childbirth and the six

weeks following, a woman shall enjoy obligatory vacation from work on

pay at the same rate, retaining her employment and all the rights

pertaining to such employment and to her labour contract. During the

nursing period, two extraordinary daily rest periods of a half hour each

shall be allowed her to feed her child.

Developing nations

In many countries, particularly those with a generally poor level of health, malnutrition is the major cause of death in children under 5, with 50% of all those cases being within the first year of life. International organisations such as Plan International and La Leche League

have helped to promote breastfeeding around the world, educating new

mothers and helping the governments to develop strategies to increase

the number of women exclusively breastfeeding.

Traditional beliefs in many developing countries give different advice to women raising their newborn child. In Ghana

babies are still frequently fed with tea alongside breastfeeding,

reducing the benefits of breastfeeding and inhibiting the absorption of

iron, important in the prevention of anaemia.

Publicity, promotion and law

In

response to public pressure, the health departments of various

governments have recognised the importance of encouraging mothers to

breastfeed. The required provision of baby changing facilities

was a large step towards making public places more accessible for

parents and in many countries there are now laws in place to protect the

rights of a breastfeeding mother when feeding her child in public.

The World Health Organization (WHO), along with grassroots non-governmental organisations like the International Baby Food Action Network

(IBFAN) have played a large role in encouraging these governmental

departments to promote breastfeeding. Under this advice they have

developed national breastfeeding strategies, including the promotion of

its benefits and attempts to encourage mothers, particularly those under

the age of 25, to choose to feed their child with breast milk.

Government campaigns and strategies around the world include:

- National Breastfeeding Week in the United Kingdom

- The Department of Health and Ageing Breastfeeding Strategy in Australia

- The National Women's Health Information Center in the United States

- World Breastfeeding Week

However, there has been a long, ongoing struggle between corporations

promoting artificial substitutes and grassroots organisations and WHO

promoting breastfeeding. The International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes

was developed in 1981 by WHO, but violations have been reported by

organisations, including those networked in IBFAN. In particular, Nestlé

took three years before it initially implemented the code, and in the

late 1990s and early 2000s was again found in violation. Nestlé had

previously faced a boycott, beginning in the U.S. but soon spreading through the rest of the world, for marketing practices in the third world (see Nestlé boycott).

Breastfeeding in public

A breastfeeding mother in public

with her baby will often need to breastfeed her child. A baby's need to

feed cannot be determined by a set schedule, so legal and social rules

about indecent exposure and dress code are often adapted to meet this need.

Many laws around the world make public breastfeeding legal and disallow

companies from prohibiting it in the workplace, but the reaction of

some people to the sight of breastfeeding can make things uncomfortable

for those involved. Some breastfeeding mothers feel reluctant to breastfeed in public.

USA

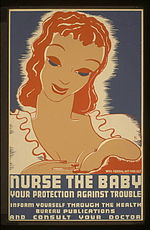

WPA poster, 1938

A United States House of Representatives appropriations bill (HR 2490) with a breastfeeding amendment

was signed into law on September 29, 1999. It stipulated that no

government funds may be used to enforce any prohibition on women

breastfeeding their children in Federal buildings or on Federal

property. Further, U.S. Public Law 106-58 Sec. 647

enacted in 1999, specifically provides that "a woman may breastfeed her

child at any location in a Federal building or on Federal property, if

the woman and her child are otherwise authorized to be present at the

location." A majority of states have enacted state statutes

specifically permitting the exposure of the female breast by women

breastfeeding infants, or exempting such women from prosecution under

applicable statutes, such as those regarding indecent exposure.

Most, but not all, state laws

have affirmed the same right in their public places. By June 2006, 36

states had enacted legislation to protect breastfeeding mothers and

their children. Laws protecting the right to nurse aim to change

attitudes and promote increased incidence and duration of breastfeeding. Recent attempts to codify a child's right to nurse were unsuccessful in West Virginia and other states. Breastfeeding in public is legal in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

UK

A UK Department

of Health survey found that 84% find breastfeeding in public acceptable

if done discreetly; however, 67% mothers are worried about general

opinion being against public breastfeeding. In Scotland, a bill safeguarding the freedom of women to breastfeed in public was passed in 2005 by the Scottish Parliament. The legislation allows for fines of up to £2500 for preventing breastfeeding in legally permitted places.

Canada

In Canada, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms gives some protection under sex equality. Although Canadian human rights protection does not explicitly include breastfeeding, a 1989 Supreme Court of Canada decision (Brooks v. Safeway Canada)

set the precedent for pregnancy as a condition unique to women and that

thus discrimination on the basis of pregnancy is a form of sex discrimination. Canadian legal precedent also allows women the right to bare their breasts, just as men may. In British Columbia,

the British Columbia Human Rights Commission Policy and Procedures

Manual protects the rights of female workers who wish to breastfeed.

Recent global uptake

The following table shows the uptake of exclusive breastfeeding.

| Country | Percentage | Year | Type of feeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Armenia | 0.7% | 1993 | Exclusive |

| 20.8% | 1997 | Exclusive | |

| Benin | 13% | 1996 | Exclusive |

| 16% | 1997 | Exclusive | |

| Bolivia | 59% | 1989 | Exclusive |

| 53% | 1994 | Exclusive | |

| Central African Republic | 4% | 1995 | Exclusive |

| Chile | 97% | 1993 | Predominant |

| Colombia | 19% | 1993 | Exclusive |

| 95% (16%) | 1995 | Predominant (exclusive) | |

| Dominican Republic | 14% | 1986 | Exclusive |

| 10% | 1991 | Exclusive | |

| Ecuador | 96% | 1994 | Predominant |

| Egypt | 68% | 1995 | Exclusive |

| Ethiopia | 78% | 2000 | Exclusive |

| Mali | 8% | 1987 | Exclusive |

| 12% | 1996 | Exclusive | |

| Mexico | 37.5% | 1987 | Exclusive |

| Niger | 4% | 1992 | Exclusive |

| Nigeria | 2% | 1992 | Exclusive |

| Pakistan | 12% | 1988 | Exclusive |

| 25% | 1992 | Exclusive | |

| Poland | 1.5% | 1988 | Exclusive |

| 17% | 1995 | Exclusive | |

| Saudi Arabia | 55% | 1991 | Exclusive |

| Senegal | 7% | 1993 | Exclusive |

| South Africa | 10.4% | 1998 | Exclusive |

| Sweden | 55% | 1992 | Exclusive |

| 98% | 1990 | Predominant | |

| 61% | 1993 | Exclusive | |

| Thailand | 90% | 1987 | Predominant |

| 99% (0.2%) | 1993 | Predominant (exclusive) | |

| 4% | 1996 | Exclusive | |

| United Kingdom | 62% | 1990 |

|

| 66% | 1995 |

| |

| Zambia | 13% | 1992 | Exclusive |

| 23% | 1996 | Exclusive | |

| Zimbabwe | 12% | 1988 | Exclusive |

| 17% | 1994 | Exclusive | |

| 38.9% | 1999 | Exclusive |

Alternatives

Direct udder nursing 1895

If a mother cannot feed her baby herself, and no wet nurse is

available, then other alternatives have to be found, usually animal

milk. In addition, once the mother begins to wean her child, the first

food is very important.

Feeding vessels dating from about 2000 BC have been found in

Egypt. A mother holding a very modern-looking nursing bottle in one hand

and a stick, presumably to mix the food, in the other is depicted in a

relief found in the ruins of the palace of King Ashurbanipal of Nineveh, who died in 888 BC. Clay feeding vessels were found in graves with infants from the first to fifth centuries AD in Rome.

Valerie Fildes writes in her book Breasts, bottles and babies. A history of Infant Feeding

about examples from the 9th to 15th centuries of children getting

animal's milk. In the 17th and 18th century Icelandic babies got cow's

milk with cream and butter. Human–animal breastfeeding shows that many babies were fed more or less directly from animals, particularly goats.

In 1582, the Italian physician Geronimo Mercuriali wrote in De morbis mulieribus (On the diseases of women) that women generally finished breastfeeding an infant exclusively after the third month and entirely around 13 months of age.

The feeding of flour or cereal mixed with broth

or water became the next alternative in the 19th century, but once

again quickly faded. Around this time there became an obvious disparity

in the feeding habits of those living in rural areas and those in urban

areas. Most likely due to the availability of alternative foods, babies

in urban areas were breastfed for a much shorter length of time,

supplementing the feeds earlier than those in rural areas.

Though first developed by Henri Nestlé in the 1860s, infant formula received a huge boost during the post–World War II baby boom. When business and births decreased, and government strategies in industrialised countries attempted to highlight the benefits of breastfeeding, Nestlé and other such companies focused their aggressive marketing campaigns on developing countries. In 1979 the International Baby Food Action Network (IBFAN) was formed to help raise awareness of such practices as supplementary feeding of new babies

with formula and the inappropriate promotion of baby formula, and to

help change attitudes that discourage or inhibit mothers from

breastfeeding their babies.