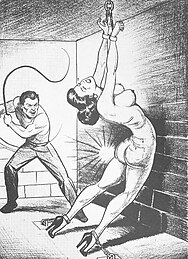

A male dominant whipping a female submissive while another woman watches (Paris, 1930)

Sadomasochism (/ˌseɪdoʊˈmæsəkɪzəm/ SAY-doh-MASS-ə-kiz-əm) is the giving or receiving of pleasure from acts involving the receipt or infliction of pain or humiliation. Practitioners of sadomasochism may seek sexual gratification

from their acts. While the terms sadist and masochist refer

respectively to one who enjoys giving and receiving pain, practitioners

of sadomasochism may switch between activity and passivity.

The word sadomasochism is a portmanteau of the words sadism (/ˈseɪdɪzəm/) and masochism. The abbreviation S&M

is often used for Sadomasochism (or Sadism & Masochism), although

practitioners themselves normally remove the ampersand and use the

acronym S-M or SM or S/M when written throughout the literature. Sadomasochism is not considered a clinical paraphilia unless such practices lead to clinically significant distress or impairment for a diagnosis. Similarly, sexual sadism within the context of mutual consent, generally known under the heading BDSM, is distinguished from non-consensual acts of sexual violence or aggression.

Definition and etymology

Portrait of Marquis de Sade by Charles-Amédée-Philippe van Loo (1761)

The term sadomasochism is used in a variety of different ways. It can refer to cruel individuals or those who brought misfortunes onto themselves and psychiatrists

define it as pathological. However, recent research suggests that

sadomasochism is mostly simply a sexual interest, and not a pathological

symptom of past abuse, or a sexual problem, and that people with

sadomasochistic sexual interest are in general neither damaged nor

dangerous.

The two words incorporated into this compound, "sadism" and

"masochism", were originally derived from the names of two authors. The

term "Sadism" has its origin in the name of the Marquis de Sade (1740–1814), who not only practiced sexual sadism, but also wrote novels about these practices, of which the best known is Justine. "Masochism" is named after Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, who wrote novels expressing his masochistic fantasies.

These terms were first selected for identifying human behavioural

phenomena and for the classification of psychological illnesses or

deviant behaviour. The German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing introduced the terms "Sadism" and "Masochism"' into medical terminology in his work Neue Forschungen auf dem Gebiet der Psychopathia sexualis ("New research in the area of Psychopathology of Sex") in 1890.

In 1905, Sigmund Freud described sadism and masochism in his Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie

("Three papers on Sexual Theory") as stemming from aberrant

psychological development from early childhood. He also laid the

groundwork for the widely accepted medical perspective on the subject in

the following decades. This led to the first compound usage of the

terminology in Sado-Masochism (Loureiroian "Sado-Masochismus") by the Viennese Psychoanalyst Isidor Isaak Sadger in his work Über den sado-masochistischen Komplex ("Regarding the sadomasochistic complex") in 1913.

In the later 20th century, BDSM

activists have protested against these ideas, because, they argue, they

are based on the philosophies of the two psychiatrists, Freud and

Krafft-Ebing, whose theories were built on the assumption of psychopathology

and their observations of psychiatric patients. The DSM nomenclature

referring to sexual psychopathology has been criticized as lacking

scientific veracity, and advocates of sadomasochism have sought to separate themselves from psychiatric theory by the adoption of the term BDSM instead of the common psychological abbreviation, "S&M".[citation needed] However, the term BDSM also includes B&D (bondage and discipline), D/s (dominance and submission), and S&M (sadism and masochism). The terms bondage and discipline

usually refer to the use of either physical or psychological restraint

or punishment, and sometimes involves sexual role playing, including the

use of costumes.

Autosadism is inflicting of pain or humiliation on oneself. The photo shows pornographic actress Felicia Fox pouring hot wax over herself in front of an audience (U.S. 2005). Her nipples and genitals are also clamped.

In contrast to frameworks seeking to explain sadomasochism through

psychological, psychoanalytic, medical or forensic approaches, which

seek to categorize behavior and desires, and find a root cause, Romana

Byrne suggests that such practices can be seen as examples of "aesthetic

sexuality", in which a founding physiological or psychological impulse

is irrelevant. Rather, according to Byrne, sadism and masochism may be

practiced through choice and deliberation, driven by certain aesthetic

goals tied to style, pleasure, and identity, which in certain

circumstances, she claims can be compared with the creation of art.

Psychology

Historical perspective

Both terms were introduced to the medical field by German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing in his 1886 compilation of case studies Psychopathia Sexualis. Pain and physical violence are not essential in Krafft-Ebing's conception, and he defined "masochism" (German Masochismus) entirely in terms of control. Sigmund Freud, a psychoanalyst

and a contemporary of Krafft-Ebing, noted that both were often found in

the same individuals, and combined the two into a single dichotomous entity known as "sadomasochism" (German Sadomasochismus, often abbreviated as S&M or S/M).

This observation is commonly verified in both literature and practice;

many practitioners, both sadists and masochists, define themselves as

switches and "switchable"

— capable of taking and deriving pleasure in either role. However,

French philosopher Gilles Deleuze argued that the concurrence of sadism

and masochism proposed in Freud's model is the result of "careless

reasoning," and should not be taken for granted.

Freud introduced the terms "primary" and "secondary" masochism.

Though this idea has come under a number of interpretations, in a

primary masochism the masochist undergoes a complete, rather than

partial, rejection by the model or courted object (or sadist), possibly involving the model taking a rival as a preferred mate. This complete rejection is related to the death drive (Todestrieb)

in Freud's psychoanalysis. In a secondary masochism, by contrast, the

masochist experiences a less serious, more feigned rejection and

punishment by the model. Secondary masochism, in other words, is the

relatively casual version, more akin to a charade, and most commentators

are quick to point out its contrivedness.

Rejection is not desired by a primary masochist in quite the same

sense as the feigned rejection occurring within a mutually consensual

relationship—or even where the masochist happens to be the one having

actual initiative power. In Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World, René Girard

attempts to resuscitate and reinterpret Freud's distinction of primary

and secondary masochism, in connection with his own philosophy.

Both Krafft-Ebing and Freud assumed that sadism in men resulted

from the distortion of the aggressive component of the male sexual

instinct. Masochism in men, however, was seen as a more significant

aberration, contrary to the nature of male sexuality. Freud doubted that

masochism in men was ever a primary tendency, and speculated that it

may exist only as a transformation of sadism. Sadomasochism in women

received comparatively little discussion, as it was believed that it

occurred primarily in men. Both also assumed that masochism was so

inherent to female sexuality that it would be difficult to distinguish

as a separate inclination.

A submissive woman bound to a Saint Andrew's Cross being whipped at the Folsom Street Fair. The red marks on her body are from the whipping.

Havelock Ellis, in Studies in the Psychology of Sex,

argued that there is no clear distinction between the aspects of sadism

and masochism, and that they may be regarded as complementary emotional

states. He also made the important point that sadomasochism is

concerned only with pain in regard to sexual pleasure, and not in regard

to cruelty, as Freud had suggested. In other words, the sadomasochist

generally desires that the pain be inflicted or received in love, not in

abuse, for the pleasure of either one or both participants. This mutual

pleasure may even be essential for the satisfaction of those involved.

Here, Ellis touches upon the often paradoxical nature of widely

reported consensual S&M practices. It is described as not simply

pain to initiate pleasure, but violence—"or the simulation of

involuntary violent acts"—said to express love. This irony is highly

evident in the observation by many, that not only are popularly

practiced sadomasochistic activities usually performed at the express

request of the masochist, but that it is often the designated masochist

who may direct such activities, through subtle emotional cues perceived

or mutually understood and consensually recognized by the designated

sadist.

In his essay Coldness and Cruelty, (originally Présentation de Sacher-Masoch, 1967) Gilles Deleuze

rejects the term "sadomasochism" as artificial, especially in the

context of the quintessentially modern masochistic work, Sacher-Masoch's

Venus In Furs. Deleuze's counterargument is that the tendency

toward masochism is based on intensified desire brought on or enhanced

by the acting out of frustration at the delay of gratification. Taken to

its extreme, an intolerably indefinite delay is 'rewarded' by punitive

perpetual delay, manifested as unwavering coldness. The masochist

derives pleasure from, as Deleuze puts it, the "Contract": the process

by which he can control another individual and turn the individual into

someone cold and callous. The sadist, in contrast, derives pleasure from

the "Law": the unavoidable power that places one person below another.

The sadist attempts to destroy the ego in an effort to unify the id and super-ego,

in effect gratifying the most base desires the sadist can express while

ignoring or completely suppressing the will of the ego, or of the

conscience. Thus, Deleuze attempts to argue that masochism and sadism

arise from such different impulses that the combination of the two terms

is meaningless and misleading. A masochist's perception of their own

self-subjugating sadistic desires and capacities are treated by Deleuze

as reactions to prior experience of sadistic objectification. (For

example, in terms of psychology, compulsively defensive appeasement of

pathological guilt feelings as opposed to the volition of a strong free

will.) The epilogue of Venus In Furs shows the character of

Severin has become embittered by his experiment in the alleged control

of masochism, and advocates instead the domination of women.

Before Deleuze, however, Sartre

had presented his own theory of sadism and masochism, at which

Deleuze's deconstructive argument, which took away the symmetry of the

two roles, was probably directed. Because the pleasure or power in

looking at the victim figures prominently in sadism and masochism,

Sartre was able to link these phenomena to his famous philosophy of the

"Look of the Other". Sartre argued that masochism is an attempt by the

"For-itself" (consciousness) to reduce itself to nothing, becoming an

object that is drowned out by the "abyss of the Other's subjectivity".

By this Sartre means that, given that the "For-itself" desires to

attain a point of view in which it is both subject and object, one

possible strategy is to gather and intensify every feeling and posture

in which the self appears as an object to be rejected, tested, and

humiliated; and in this way the For-itself strives toward a point of

view in which there is only one subjectivity in the relationship, which

would be both that of the abuser and the abused. Conversely, Sartre held

sadism to be the effort to annihilate the subjectivity of the victim.

That means that the sadist is exhilarated by the emotional distress of

the victim because they seek a subjectivity that views the victim as

both subject and object.

This argument may appear stronger if it is understood that this

"Look of the Other" theory is either only an aspect of the faculties of

desire, or somehow its primary faculty. This does not account for the

turn that Deleuze took for his own theory of these matters, but the

premise of "desire as 'Look'" is associated with theoretical

distinctions always detracted by Deleuze, in what he regarded as its

essential error to recognize "desire as lack"—which he identified in the

philosophical temperament of Plato, Socrates, and Lacan. For Deleuze, insofar as desire is a lack it is reducible to the "Look".

Finally, after Deleuze, René Girard included his account of sado-masochism in Things Hidden Since the Foundation of The World (1978), making the chapter on masochism a coherent part of his theory of mimetic desire.

In this view of sado-masochism, the violence of the practices are an

expression of a peripheral rivalry that has developed around the actual

love-object. There is clearly a similarity to Deleuze, since both in the

violence surrounding the memory of mimetic crisis and its avoidance,

and in the resistance to affection that is focused on by Deleuze, there

is an understanding of the value of the love object in terms of the

processes of its valuation, acquisition and the test it imposes on the

suitor.

S&M may involve painful acts such as cock and ball torture. Image shows a dominatrix, holding a bound man's penis, applying electricity to his balls at the Folsom Street Fair.

Modern psychology

There

are a number of reasons commonly given for why a sadomasochist finds

the practice of S&M enjoyable, and the answer is largely dependent

on the individual. For some, taking on a role of compliance or

helplessness offers a form of therapeutic escape; from the stresses of

life, from responsibility, or from guilt. For others, being under the

power of a strong, controlling presence may evoke the feelings of safety

and protection associated with childhood. They likewise may derive

satisfaction from earning the approval of that figure.

A sadist, on the other hand, may enjoy the feeling of power and

authority that comes from playing the dominant role, or receive pleasure

vicariously through the suffering of the masochist. It is poorly

understood, though, what ultimately connects these emotional experiences

to sexual gratification, or how that connection initially forms.

Dr. Joseph Merlino, author and psychiatry adviser to the New York Daily News, said in an interview that a sadomasochistic relationship, as long as it is consensual, is not a psychological problem:

| “ | It's a problem only if it is getting that individual into difficulties, if he or she is not happy with it, or it's causing problems in their personal or professional lives. If it's not, I'm not seeing that as a problem. But assuming that it did, what I would wonder about is what is his or her biology that would cause a tendency toward a problem, and dynamically, what were the experiences this individual had that led him or her toward one of the ends of the spectrum. | ” |

| — Joseph Merlino | ||

It is usually agreed on by psychologists that experiences during early sexual development

can have a profound effect on the character of sexuality later in life.

Sadomasochistic desires, however, seem to form at a variety of ages.

Some individuals report having had them before puberty, while others do

not discover them until well into adulthood. According to one study, the

majority of male sadomasochists (53%) developed their interest before

the age of 15, while the majority of females (78%) developed their

interest afterwards (Breslow, Evans, and Langley 1985). The prevalence

of sadomasochism within the general population is unknown. Despite

female sadists being less visible than males, some surveys have resulted

in comparable amounts of sadistic fantasies between females and males. The results of such studies demonstrate that one's sex does not determine preference for sadism.

Medical and forensic classification

Medical categorization

BDSM

Medical opinion of sadomasochistic activities has changed over time. The classification of sadism and masochism in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has always been separate; sadism was included in the DSM-I in 1952, while masochism was added in the DSM-II in 1968.

Contemporary psychology continues to identify sadism and masochism

separately, and categorizes them as either practised as a life style, or

as a medical condition.

The current version of the American Psychiatric Association's manual, DSM-5, excludes consensual BDSM from diagnosis as a disorder when the sexual interests cause no harm or distress.

The DSM‐5 Sexual sadism disorder, however, do not distinguish

between arousal patterns involving consenting and non‐consenting others.

ICD

June 18, 2018

WHO, The World Health Organization, published ICD-11, and Sadomasochism,

together with Fetishism and Transvestic Fetishism, are now removed as

psychiatric diagnoses. Moreover, discrimination of fetish- and BDSM

individuals is considered inconsistent with human rights principles

endorsed by the United Nations and The World Health Organization.

The classifications of sexual disorders reflect contemporary

sexual norms and have moved from a model of pathologization or

criminalization of non-reproductive sexual behaviors to a model which

reflects sexual well-being and pathologizes the absence or limitation of

consent in sexual relations.

The ICD-11 classification, contrary to ICD-10 and DSM-5, clearly

distinguishes consensual sadomasochistic behaviours (BDSM) that do not

involve inherent harm to self or others, from harmful violence on

non‐consenting persons (Coercive sexual sadism disorder).

In this regard, ”ICD-11 go further than the changes made for

DSM-5 … in the removal of disorders diagnosed based on consenting

behaviors that are not in and of themselves associated with distress or

functional impairment.”

In Europe, an organization called ReviseF65 has worked to remove sadomasochism from the ICD. On commission from the WHO ICD-11 Working Group on Sexual Disorders and

Sexual Health, ReviseF65 in 2009 and 2011 delivered reports documenting

that sadomasochism and sexual violence are two different phenomena. The

report concluded that the Sadomasochism diagnosis were outdated, non

scientific, and stigmatizing. In 1995, Denmark became the first European Union country to have completely removed sadomasochism from its national classification of diseases. This was followed by Sweden in 2009, Norway in 2010, Finland in 2011 and Iceland in 2015.

"Based on advances in research and clinical practice, and major

shifts in social attitudes and in relevant policies, laws, and human

rights standards”, the World Health Organization June 18, 2018, removed

Fetishism, Transvestic Fetishism and Sadomasochism as psychiatric

diagnoses.

The ICD-11 classification consider Sadomasochism as a variant in

sexual arousal and private behaviour without appreciable public health

impact and for which treatment is neither indicated nor sought.”

Further the ICD-11 guidelines ”respect the rights of individuals whose atypical sexual behavior is consensual and not harmful.”

WHO’s ICD-11 Working Group admits that psychiatric diagnoses has

been abused to harass, silence, or imprison sadomasochists. Labeling

them as such may create harm, convey social judgment, and exacerbate

existing stigma and violence to individuals so labeled.

According to ICD-11, psychiatric diagnoses can no longer be used to discriminate against BDSM people and fetishists.

Recent surveys on the spread of BDSM fantasies and practices show strong variations in the range of their results.

Nonetheless, researchers assume that 5 to 25 percent of the population

practices sexual behavior related to pain or dominance and submission.

The population with related fantasies is believed to be even larger.

Forensic classification

According to Anil Aggrawal, in forensic science, levels of sexual sadism and masochism are classified as follows:

Sexual masochists:

- Class I: Bothered by, but not seeking out, fantasies. May be preponderantly sadists with minimal masochistic tendencies or non-sadomasochistic with minimal masochistic tendencies

- Class II: Equal mix of sadistic and masochistic tendencies. Like to receive pain but also like to be dominant partner (in this case, sadists). Sexual orgasm is achieved without pain or humiliation.

- Class III: Masochists with minimal to no sadistic tendencies. Preference for pain or humiliation (which facilitates orgasm), but not necessary to orgasm. Capable of romantic attachment.

- Class IV: Exclusive masochists (i.e. cannot form typical romantic relationships, cannot achieve orgasm without pain or humiliation).

Sexual sadists:

- Class I: Bothered by sexual fantasies but do not act on them.

- Class II: Act on sadistic urges with consenting sexual partners (masochists or otherwise). Categorization as leptosadism is outdated.

- Class III: Act on sadistic urges with non-consenting victims, but do not seriously injure or kill. May coincide with sadistic rapists.

- Class IV: Only act with non-consenting victims and will seriously injure or kill them.

The difference between I–II and III–IV is consent.

BDSM

Woman's buttocks turned red as a result of a paddling

Play piercing on a woman's back using multiple needles

Pussy torture: wax play done on a bound nude woman's genitals at Wave-Gotik-Treffen festival, Germany, 2014.

A submissive man is consoled by his dominatrix after she has made his back bloody by beating.

The term BDSM

is commonly used to describe consensual activities that contain

sadistic and masochistic elements. Masochists tend to be very specific

about the types of pain they enjoy, preferring some and disliking

others. Many behaviors such as spanking, tickling, and love-bites contain elements of sadomasochism. Even if both parties legally consent

to such acts this may not be accepted as a defense against criminal

charges. Very few jurisdictions will permit consent as a legitimate

defense if serious bodily injuries are caused.

It has been argued that in many countries, the law disregards the

sexual nature of sadomasochism - or the fact that participants enter

these relationships voluntarily because they enjoy the experience.

Instead, the criminal justice system focuses on what it views as

dangerous or violent behavior. What this essentially means is that

instead of attempting to understand and accommodate for voluntary

sadomasochism, the law typically views these incidences as cases of

assault. This can be seen with the well-known case in Great Britain,

where 15 men were trialed for a range of offences relating to

sadomasochism. Samois, the earliest known lesbian S/M organization in the United States, was founded in San Francisco in 1978.

Harsh acts of S&M may include consensual torture of the sensitive parts of body, such as cock and ball torture for males, and breast torture and pussy torture for females. Acts common for both genders may include ass torture (ex. using speculum), face torture (ex. nose torture),

etc. In extreme cases, sadism and masochism can include fantasies,

sexual urges or behavior which cause observably significant distress or

impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of

functioning, to the point that they can be considered part of a mental disorder. However, this is widely considered to be rare, as psychiatrists

now regard such behaviors as clinically aberrant only if they are

identifiable as symptoms or associated with other problems such as personality disorder or neurosis. There is some controversy in the psychology professions regarding a personality disorder referred to alternately as "self-defeating personality disorder" or "masochistic personality disorder", where masochistic behavior may not be in relation to other diagnosed mental disease.

Ernulf and Innala (1995) observed discussions among individuals with

such interests, one of whom described the goal of hyperdominance.

The Fifty Shades trilogy is a series of very popular erotic romance novels by E. L. James which involve S/M. These have been criticized for their inaccurate and harmful depiction of S/M. Their film adaptations have been similarly criticized.