Energy storage is the capture of energy produced at one time for use at a later time. A device that stores energy is generally called an accumulator or battery. Energy comes in multiple forms including radiation, chemical, gravitational potential, electrical potential, electricity, elevated temperature, latent heat and kinetic. Energy storage involves converting energy from forms that are difficult to store to more conveniently or economically storable forms.

Some technologies provide short-term energy storage, while others can endure for much longer. Bulk energy storage is currently dominated by hydroelectric dams, both conventional as well as pumped. Grid energy storage is a collection of methods used for energy storage on a large scale within an electrical power grid.

Common examples of energy storage are the rechargeable battery, which stores chemical energy readily convertible to electricity to operate a mobile phone, the hydroelectric dam, which stores energy in a reservoir as gravitational potential energy, and ice storage tanks, which store ice frozen by cheaper energy at night to meet peak daytime demand for cooling. Fossil fuels such as coal and gasoline store ancient energy derived from sunlight by organisms that later died, became buried and over time were then converted into these fuels. Food (which is made by the same process as fossil fuels) is a form of energy stored in chemical form.

History

Recent history

In the 20th century grid, electrical power was largely generated by burning fossil fuel. When less power was required, less fuel was burned. Concerns with air pollution, energy imports, and global warming have spawned the growth of renewable energy such as solar and wind power. Wind power is uncontrolled and may be generating at a time when no additional power is needed. Solar power varies with cloud cover and at best is only available during daylight hours, while demand often peaks after sunset (see duck curve). Interest in storing power from these intermittent sources grows as the renewable energy industry begins to generate a larger fraction of overall energy consumption.

Off grid electrical use was a niche market in the 20th century, but in the 21st century, it has expanded. Portable devices are in use all over the world. Solar panels are now common in the rural settings worldwide. Access to electricity is now a question of economics and financial viability, and not solely on technical aspects. However, powering transportation without burning fuel remains in development.

Methods

Outline

The following list includes a variety of types of energy storage:

- Fossil fuel storage

- Mechanical

- Spring

- Compressed air energy storage (CAES)

- Fireless locomotive

- Flywheel energy storage

- Solid mass gravitational

- Hydraulic accumulator

- Pumped-storage hydroelectricity (pumped hydroelectric storage, PHS, or pumped storage hydropower, PSH)

- Electrical, electromagnetic

- Capacitor

- Supercapacitor

- Superconducting magnetic energy storage (SMES, also superconducting storage coil)

- Biological

- Electrochemical (Battery Energy Storage System, BESS)

- Thermal

- Chemical

Mechanical

Energy can be stored in water pumped to a higher elevation using pumped storage methods or by moving solid matter to higher locations (gravity batteries). Other commercial mechanical methods include compressing air and flywheels that convert electric energy into internal energy or kinetic energy and then back again when electrical demand peaks.

Hydroelectricity

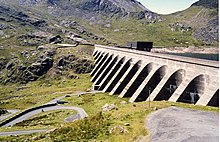

Hydroelectric dams with reservoirs can be operated to provide electricity at times of peak demand. Water is stored in the reservoir during periods of low demand and released when demand is high. The net effect is similar to pumped storage, but without the pumping loss.

While a hydroelectric dam does not directly store energy from other generating units, it behaves equivalently by lowering output in periods of excess electricity from other sources. In this mode, dams are one of the most efficient forms of energy storage, because only the timing of its generation changes. Hydroelectric turbines have a start-up time on the order of a few minutes.

Pumped hydro

Worldwide, pumped-storage hydroelectricity (PSH) is the largest-capacity form of active grid energy storage available, and, as of March 2012, the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) reports that PSH accounts for more than 99% of bulk storage capacity worldwide, representing around 127,000 MW. PSH energy efficiency varies in practice between 70% and 80%, with claims of up to 87%.

At times of low electrical demand, excess generation capacity is used to pump water from a lower source into a higher reservoir. When demand grows, water is released back into a lower reservoir (or waterway or body of water) through a turbine, generating electricity. Reversible turbine-generator assemblies act as both a pump and turbine (usually a Francis turbine design). Nearly all facilities use the height difference between two water bodies. Pure pumped-storage plants shift the water between reservoirs, while the "pump-back" approach is a combination of pumped storage and conventional hydroelectric plants that use natural stream-flow.

Compressed air

Compressed air energy storage (CAES) uses surplus energy to compress air for subsequent electricity generation. Small-scale systems have long been used in such applications as propulsion of mine locomotives. The compressed air is stored in an underground reservoir, such as a salt dome.

Compressed-air energy storage (CAES) plants can bridge the gap between production volatility and load. CAES storage addresses the energy needs of consumers by effectively providing readily available energy to meet demand. Renewable energy sources like wind and solar energy vary. So at times when they provide little power, they need to be supplemented with other forms of energy to meet energy demand. Compressed-air energy storage plants can take in the surplus energy output of renewable energy sources during times of energy over-production. This stored energy can be used at a later time when demand for electricity increases or energy resource availability decreases.

Compression of air creates heat; the air is warmer after compression. Expansion requires heat. If no extra heat is added, the air will be much colder after expansion. If the heat generated during compression can be stored and used during expansion, efficiency improves considerably. A CAES system can deal with the heat in three ways. Air storage can be adiabatic, diabatic, or isothermal. Another approach uses compressed air to power vehicles.

Flywheel

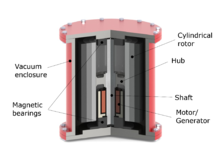

Flywheel energy storage (FES) works by accelerating a rotor (a flywheel) to a very high speed, holding energy as rotational energy. When energy is added the rotational speed of the flywheel increases, and when energy is extracted, the speed declines, due to conservation of energy.

Most FES systems use electricity to accelerate and decelerate the flywheel, but devices that directly use mechanical energy are under consideration.

FES systems have rotors made of high strength carbon-fiber composites, suspended by magnetic bearings and spinning at speeds from 20,000 to over 50,000 revolutions per minute (rpm) in a vacuum enclosure. Such flywheels can reach maximum speed ("charge") in a matter of minutes. The flywheel system is connected to a combination electric motor/generator.

FES systems have relatively long lifetimes (lasting decades with little or no maintenance; full-cycle lifetimes quoted for flywheels range from in excess of 105, up to 107, cycles of use), high specific energy (100–130 W·h/kg, or 360–500 kJ/kg) and power density.

Solid mass gravitational

Changing the altitude of solid masses can store or release energy via an elevating system driven by an electric motor/generator. Studies suggest energy can begin to be released with as little as 1 second warning, making the method a useful supplemental feed into an electricity grid to balance load surges.

Efficiencies can be as high as 85% recovery of stored energy.

This can be achieved by siting the masses inside old vertical mine shafts or in specially constructed towers where the heavy weights are winched up to store energy and allowed a controlled descent to release it. At 2020 a prototype vertical store is being built in Edinburgh , Scotland

Potential energy storage or gravity energy storage was under active development in 2013 in association with the California Independent System Operator. It examined the movement of earth-filled hopper rail cars driven by electric locomotives from lower to higher elevations.er proposed methods include:-

- using rails and cranes to move concrete weights up and down;

- using high-altitude solar-powered balloon platforms supporting winches to raise and lower solid masses slung underneath them,

- using winches supported by an ocean barge to take advantage of a 4 km (13,000 ft) elevation difference between the sea surface and the seabed,

Thermal

Thermal energy storage (TES) is the temporary storage or removal of heat.

Sensible heat thermal

Sensible heat storage take advantage of sensible heat in a material to store energy.

Seasonal thermal energy storage (STES) allows heat or cold to be used months after it was collected from waste energy or natural sources. The material can be stored in contained aquifers, clusters of boreholes in geological substrates such as sand or crystalline bedrock, in lined pits filled with gravel and water, or water-filled mines. Seasonal thermal energy storage (STES) projects often have paybacks in four to six years. An example is Drake Landing Solar Community in Canada, for which 97% of the year-round heat is provided by solar-thermal collectors on the garage roofs, with a borehole thermal energy store (BTES) being the enabling technology. In Braedstrup, Denmark, the community's solar district heating system also uses STES, at a temperature of 65 °C (149 °F). A heat pump, which is run only when there is surplus wind power available on the national grid, is used to raise the temperature to 80 °C (176 °F) for distribution. When surplus wind generated electricity is not available, a gas-fired boiler is used. Twenty percent of Braedstrup's heat is solar.

Latent heat thermal (LHTES)

Latent heat thermal energy storage systems work by transferring heat to or from a material to change its phase. A phase-change is the melting, solidifying, vaporizing or liquifying. Such a material is called a phase change material (PCM). Materials used in LHTESs often have a high latent heat so that at their specific temperature, the phase change absorbs a large amount of energy, much more than sensible heat.

A steam accumulator is a type of LHTES where the phase change is between liquid and gas and uses the latent heat of vaporization of water.

Cryogenic thermal energy storage

Air can be liquefied by cooling using electricity and stored as a cryogen with existing technologies.. The liquid air can then be expanded through a turbine and the energy recovered as electricity. The system was demonstrated at a pilot plant in the UK in 2012 . [38]

Electrochemical

Rechargeable battery

A rechargeable battery comprises one or more electrochemical cells. It is known as a 'secondary cell' because its electrochemical reactions are electrically reversible. Rechargeable batteries come in many shapes and sizes, ranging from button cells to megawatt grid systems.

Rechargeable batteries have lower total cost of use and environmental impact than non-rechargeable (disposable) batteries. Some rechargeable battery types are available in the same form factors as disposables. Rechargeable batteries have higher initial cost but can be recharged very cheaply and used many times.

Common rechargeable battery chemistries include:

- Lead–acid battery: Lead acid batteries hold the largest market share of electric storage products. A single cell produces about 2V when charged. In the charged state the metallic lead negative electrode and the lead sulfate positive electrode are immersed in a dilute sulfuric acid (H2SO4) electrolyte. In the discharge process electrons are pushed out of the cell as lead sulfate is formed at the negative electrode while the electrolyte is reduced to water.

- Lead-acid battery technology has been developed extensively. Upkeep requires minimal labor and its cost is low. The battery's available energy capacity is subject to a quick discharge resulting in a low life span and low energy density.

- Nickel–cadmium battery (NiCd): Uses nickel oxide hydroxide and metallic cadmium as electrodes. Cadmium is a toxic element, and was banned for most uses by the European Union in 2004. Nickel–cadmium batteries have been almost completely replaced by nickel–metal hydride (NiMH) batteries.

- Nickel–metal hydride battery (NiMH): First commercial types were available in 1989. These are now a common consumer and industrial type. The battery has a hydrogen-absorbing alloy for the negative electrode instead of cadmium.

- Lithium-ion battery: The choice in many consumer electronics and have one of the best energy-to-mass ratios and a very slow self-discharge when not in use.

- Lithium-ion polymer battery: These batteries are light in weight and can be made in any shape desired.

Flow battery

A flow battery works by passing a solution over a membrane where ions are exchanged to charge or discharge the cell. Cell voltage is chemically determined by the Nernst equation and ranges, in practical applications, from 1.0 V to 2.2 V. Storage capacity depends on the volume of solution. A flow battery is technically akin both to a fuel cell and an electrochemical accumulator cell. Commercial applications are for long half-cycle storage such as backup grid power.

Supercapacitor

Supercapacitors, also called electric double-layer capacitors (EDLC) or ultracapacitors, are a family of electrochemical capacitors that do not have conventional solid dielectrics. Capacitance is determined by two storage principles, double-layer capacitance and pseudocapacitance.

Supercapacitors bridge the gap between conventional capacitors and rechargeable batteries. They store the most energy per unit volume or mass (energy density) among capacitors. They support up to 10,000 farads/1.2 Volt, up to 10,000 times that of electrolytic capacitors, but deliver or accept less than half as much power per unit time (power density).

While supercapacitors have specific energy and energy densities that are approximately 10% of batteries, their power density is generally 10 to 100 times greater. This results in much shorter charge/discharge cycles. Also, they tolerate many more charge-discharge cycles than batteries.

Supercapacitors have many applications, including:

- Low supply current for memory backup in static random-access memory (SRAM)

- Power for cars, buses, trains, cranes and elevators, including energy recovery from braking, short-term energy storage and burst-mode power delivery

Other chemical

Power to gas

Power to gas is the conversion of electricity to a gaseous fuel such as hydrogen or methane. The three commercial methods use electricity to reduce water into hydrogen and oxygen by means of electrolysis.

In the first method, hydrogen is injected into the natural gas grid or is used for transportation. The second method is to combine the hydrogen with carbon dioxide to produce methane using a methanation reaction such as the Sabatier reaction, or biological methanation, resulting in an extra energy conversion loss of 8%. The methane may then be fed into the natural gas grid. The third method uses the output gas of a wood gas generator or a biogas plant, after the biogas upgrader is mixed with the hydrogen from the electrolyzer, to upgrade the quality of the biogas.

Hydrogen

The element hydrogen can be a form of stored energy. Hydrogen can produce electricity via a hydrogen fuel cell.

At penetrations below 20% of the grid demand, renewables do not severely change the economics; but beyond about 20% of the total demand, external storage becomes important. If these sources are used to make ionic hydrogen, they can be freely expanded. A 5-year community-based pilot program using wind turbines and hydrogen generators began in 2007 in the remote community of Ramea, Newfoundland and Labrador. A similar project began in 2004 on Utsira, a small Norwegian island.

Energy losses involved in the hydrogen storage cycle come from the electrolysis of water, liquification or compression of the hydrogen and conversion to electricity.

About 50 kW·h (180 MJ) of solar energy is required to produce a kilogram of hydrogen, so the cost of the electricity is crucial. At $0.03/kWh, a common off-peak high-voltage line rate in the United States, hydrogen costs $1.50 per kilogram for the electricity, equivalent to $1.50/gallon for gasoline. Other costs include the electrolyzer plant, hydrogen compressors or liquefaction, storage and transportation.

Hydrogen can also be produced from aluminum and water by stripping aluminum's naturally-occurring aluminum oxide barrier and introducing it to water. This method is beneficial because recycled aluminum cans can be used to generate hydrogen, however systems to harness this option have not been commercially developed and are much more complex than electrolysis systems.mon methods to strip the oxide layer include caustic catalysts such as sodium hydroxide and alloys with gallium, mercury and other metals.

Underground hydrogen storage is the practice of hydrogen storage in caverns, salt domes and depleted oil and gas fields. Large quantities of gaseous hydrogen have been stored in caverns by Imperial Chemical Industries for many years without any difficulties. The European Hyunder project indicated in 2013 that storage of wind and solar energy using underground hydrogen would require 85 caverns.

Methane

Methane is the simplest hydrocarbon with the molecular formula CH4. Methane is more easily stored and transported than hydrogen. Storage and combustion infrastructure (pipelines, gasometers, power plants) are mature.

Synthetic natural gas (syngas or SNG) can be created in a multi-step process, starting with hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen is then reacted with carbon dioxide in a Sabatier process, producing methane and water. Methane can be stored and later used to produce electricity. The resulting water is recycled, reducing the need for water. In the electrolysis stage, oxygen is stored for methane combustion in a pure oxygen environment at an adjacent power plant, eliminating nitrogen oxides.

Methane combustion produces carbon dioxide (CO2) and water. The carbon dioxide can be recycled to boost the Sabatier process and water can be recycled for further electrolysis. Methane production, storage and combustion recycles the reaction products.

The CO2 has economic value as a component of an energy storage vector, not a cost as in carbon capture and storage.

Power to liquid

Power to liquid is similar to power to gas except that the hydrogen is converted into liquids such as methanol or ammonia. These are easier to handle than gases, and requires fewer safety precautions than hydrogen. They can be used for transportation, including aircraft, but also for industrial purposes or in the power sector.

Biofuels

Various biofuels such as biodiesel, vegetable oil, alcohol fuels, or biomass can replace fossil fuels. Various chemical processes can convert the carbon and hydrogen in coal, natural gas, plant and animal biomass and organic wastes into short hydrocarbons suitable as replacements for existing hydrocarbon fuels. Examples are Fischer–Tropsch diesel, methanol, dimethyl ether and syngas. This diesel source was used extensively in World War II in Germany, which faced limited access to crude oil supplies. South Africa produces most of the country's diesel from coal for similar reasons. A long term oil price above US$35/bbl may make such large scale synthetic liquid fuels economical.

Aluminum

Aluminum has been proposed as an energy store by a number of researchers. Its electrochemical equivalent (8.04 Ah/cm3) is nearly four times greater than that of lithium (2.06 Ah/cm3). Energy can be extracted from aluminum by reacting it with water to generate hydrogen. However, it must first be stripped of its natural oxide layer, a process which requires pulverization, chemical reactions with caustic substances, or alloys. The byproduct of the reaction to create hydrogen is aluminum oxide, which can be recycled into aluminum with the Hall–Héroult process, making the reaction theoretically renewable. If the Hall-Heroult Process is run using solar or wind power, aluminum could be used to store the energy produced at higher efficiency than direct solar electrolysis.

Boron, silicon, and zinc

Boron, silicon, and zinc have been proposed as energy storage solutions.

Other chemical

The organic compound norbornadiene converts to quadricyclane upon exposure to light, storing solar energy as the energy of chemical bonds. A working system has been developed in Sweden as a molecular solar thermal system.

Electrical methods

Capacitor

A capacitor (originally known as a 'condenser') is a passive two-terminal electrical component used to store energy electrostatically. Practical capacitors vary widely, but all contain at least two electrical conductors (plates) separated by a dielectric (i.e., insulator). A capacitor can store electric energy when disconnected from its charging circuit, so it can be used like a temporary battery, or like other types of rechargeable energy storage system. Capacitors are commonly used in electronic devices to maintain power supply while batteries change. (This prevents loss of information in volatile memory.)

Conventional capacitors provide less than 360 joules per kilogram, while a conventional alkaline battery has a density of 590 kJ/kg.

Capacitors store energy in an electrostatic field between their plates. Given a potential difference across the conductors (e.g., when a capacitor is attached across a battery), an electric field develops across the dielectric, causing positive charge (+Q) to collect on one plate and negative charge (-Q) to collect on the other plate. If a battery is attached to a capacitor for a sufficient amount of time, no current can flow through the capacitor. However, if an accelerating or alternating voltage is applied across the leads of the capacitor, a displacement current can flow. Besides capacitor plates, charge can also be stored in a dielectric layer.

Capacitance is greater given a narrower separation between conductors and when the conductors have a larger surface area. In practice, the dielectric between the plates emits a small amount of leakage current and has an electric field strength limit, known as the breakdown voltage. However, the effect of recovery of a dielectric after a high-voltage breakdown holds promise for a new generation of self-healing capacitors. The conductors and leads introduce undesired inductance and resistance.

Research is assessing the quantum effects of nanoscale capacitors for digital quantum batteries.

Superconducting magnetics

Superconducting magnetic energy storage (SMES) systems store energy in a magnetic field created by the flow of direct current in a superconducting coil that has been cooled to a temperature below its superconducting critical temperature. A typical SMES system includes a superconducting coil, power conditioning system and refrigerator. Once the superconducting coil is charged, the current does not decay and the magnetic energy can be stored indefinitely.

The stored energy can be released to the network by discharging the coil. The associated inverter/rectifier accounts for about 2–3% energy loss in each direction. SMES loses the least amount of electricity in the energy storage process compared to other methods of storing energy. SMES systems offer round-trip efficiency greater than 95%.

Due to the energy requirements of refrigeration and the cost of superconducting wire, SMES is used for short duration storage such as improving power quality. It also has applications in grid balancing.

Applications

Mills

The classic application before the industrial revolution was the control of waterways to drive water mills for processing grain or powering machinery. Complex systems of reservoirs and dams were constructed to store and release water (and the potential energy it contained) when required.

Homes

Home energy storage is expected to become increasingly common given the growing importance of distributed generation of renewable energies (especially photovoltaics) and the important share of energy consumption in buildings.[73] To exceed a self-sufficiency of 40% in a household equipped with photovoltaics, energy storage is needed.[73] Multiple manufacturers produce rechargeable battery systems for storing energy, generally to hold surplus energy from home solar or wind generation. Today, for home energy storage, Li-ion batteries are preferable to lead-acid ones given their similar cost but much better performance.[74]

Tesla Motors produces two models of the Tesla Powerwall. One is a 10 kWh weekly cycle version for backup applications and the other is a 7 kWh version for daily cycle applications. In 2016, a limited version of the Tesla Powerpack 2 cost $398(US)/kWh to store electricity worth 12.5 cents/kWh (US average grid price) making a positive return on investment doubtful unless electricity prices are higher than 30 cents/kWh.

RoseWater Energy produces two models of the "Energy & Storage System", the HUB 120 and SB20. Both versions provide 28.8 kWh of output, enabling it to run larger houses or light commercial premises, and protecting custom installations. The system provides five key elements into one system, including providing a clean 60 Hz Sine wave, zero transfer time, industrial-grade surge protection, renewable energy grid sell-back (optional), and battery backup.

Enphase Energy announced an integrated system that allows home users to store, monitor and manage electricity. The system stores 1.2 kWh of energy and 275W/500W power output.

Storing wind or solar energy using thermal energy storage though less flexible, is considerably cheaper than batteries. A simple 52-gallon electric water heater can store roughly 12 kWh of energy for supplementing hot water or space heating.

For purely financial purposes in areas where net metering is available, home generated electricity may be sold to the grid through a grid-tie inverter without the use of batteries for storage.

Grid electricity and power stations

Renewable energy

The largest source and the greatest store of renewable energy is provided by hydroelectric dams. A large reservoir behind a dam can store enough water to average the annual flow of a river between dry and wet seasons. A very large reservoir can store enough water to average the flow of a river between dry and wet years. While a hydroelectric dam does not directly store energy from intermittent sources, it does balance the grid by lowering its output and retaining its water when power is generated by solar or wind. If wind or solar generation exceeds the region's hydroelectric capacity, then some additional source of energy is needed.

Many renewable energy sources (notably solar and wind) produce variable power. Storage systems can level out the imbalances between supply and demand that this causes. Electricity must be used as it is generated or converted immediately into storable forms.

The main method of electrical grid storage is pumped-storage hydroelectricity. Areas of the world such as Norway, Wales, Japan and the US have used elevated geographic features for reservoirs, using electrically powered pumps to fill them. When needed, the water passes through generators and converts the gravitational potential of the falling water into electricity. Pumped storage in Norway, which gets almost all its electricity from hydro, has currently a capacity of 1.4 GW but since the total installed capacity is nearly 32 GW and 75% of that is regulable, it can be expanded significantly.

Some forms of storage that produce electricity include pumped-storage hydroelectric dams, rechargeable batteries, thermal storage including molten salts which can efficiently store and release very large quantities of heat energy, and compressed air energy storage, flywheels, cryogenic systems and superconducting magnetic coils.

Surplus power can also be converted into methane (sabatier process) with stockage in the natural gas network.

In 2011, the Bonneville Power Administration in Northwestern United States created an experimental program to absorb excess wind and hydro power generated at night or during stormy periods that are accompanied by high winds. Under central control, home appliances absorb surplus energy by heating ceramic bricks in special space heaters to hundreds of degrees and by boosting the temperature of modified hot water heater tanks. After charging, the appliances provide home heating and hot water as needed. The experimental system was created as a result of a severe 2010 storm that overproduced renewable energy to the extent that all conventional power sources were shut down, or in the case of a nuclear power plant, reduced to its lowest possible operating level, leaving a large area running almost completely on renewable energy.

Another advanced method used at the former Solar Two project in the United States and the Solar Tres Power Tower in Spain uses molten salt to store thermal energy captured from the sun and then convert it and dispatch it as electrical power. The system pumps molten salt through a tower or other special conduits to be heated by the sun. Insulated tanks store the solution. Electricity is produced by turning water to steam that is fed to turbines.

Since the early 21st century batteries have been applied to utility scale load-leveling and frequency regulation capabilities.

In vehicle-to-grid storage, electric vehicles that are plugged into the energy grid can deliver stored electrical energy from their batteries into the grid when needed.

Air conditioning

Thermal energy storage (TES) can be used for air conditioning. It is most widely used for cooling single large buildings and/or groups of smaller buildings. Commercial air conditioning systems are the biggest contributors to peak electrical loads. In 2009, thermal storage was used in over 3,300 buildings in over 35 countries. It works by chilling material at night and using the chilled material for cooling during the hotter daytime periods.

The most popular technique is ice storage, which requires less space than water and is cheaper than fuel cells or flywheels. In this application, a standard chiller runs at night to produce an ice pile. Water circulates through the pile during the day to chill water that would normally be the chiller's daytime output.

A partial storage system minimizes capital investment by running the chillers nearly 24 hours a day. At night, they produce ice for storage and during the day they chill water. Water circulating through the melting ice augments the production of chilled water. Such a system makes ice for 16 to 18 hours a day and melts ice for six hours a day. Capital expenditures are reduced because the chillers can be just 40% - 50% of the size needed for a conventional, no-storage design. Storage sufficient to store half a day's available heat is usually adequate.

A full storage system shuts off the chillers during peak load hours. Capital costs are higher, as such a system requires larger chillers and a larger ice storage system.

This ice is produced when electrical utility rates are lower. Off-peak cooling systems can lower energy costs. The U.S. Green Building Council has developed the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program to encourage the design of reduced-environmental impact buildings. Off-peak cooling may help toward LEED Certification.

Thermal storage for heating is less common than for cooling. An example of thermal storage is storing solar heat to be used for heating at night.

Latent heat can also be stored in technical phase change materials (PCMs). These can be encapsulated in wall and ceiling panels, to moderate room temperatures.

Transport

Liquid hydrocarbon fuels are the most commonly used forms of energy storage for use in transportation, followed by a growing use of Battery Electric Vehicles and Hybrid Electric Vehicles. Other energy carriers such as hydrogen can be used to avoid producing greenhouse gases.

Public transport systems like trams and trolleybuses require electricity, but due to their variability in movement, a steady supply of electricity via renewable energy is challenging. Photovoltaic systems installed on the roofs of buildings can be used to power public transportation systems during periods in which there is increased demand for electricity and access to other forms of energy are not readily available.

Electronics

Capacitors are widely used in electronic circuits for blocking direct current while allowing alternating current to pass. In analog filter networks, they smooth the output of power supplies. In resonant circuits they tune radios to particular frequencies. In electric power transmission systems they stabilize voltage and power flow.

Use cases

The United States Department of Energy International Energy Storage Database (IESDB), is a free-access database of energy storage projects and policies funded by the United States Department of Energy Office of Electricity and Sandia National Labs.

Capacity

Storage capacity is the amount of energy extracted from a power plant energy storage system; usually measured in joules or kilowatt-hours and their multiples, it may be given in number of hours of electricity production at power plant nameplate capacity; when storage is of primary type (i.e., thermal or pumped-water), output is sourced only with the power plant embedded storage system.

Economics

The economics of energy storage strictly depends on the reserve service requested, and several uncertainty factors affect the profitability of energy storage. Therefore, not every storage method is technically and economically suitable for the storage of several MWh, and the optimal size of the energy storage is market and location dependent.

Moreover, ESS are affected by several risks, e.g.:

1) Techno-economic risks, which are related to the specific technology;

2) Market risks, which are the factors that affect the electricity supply system;

3) Regulation and policy risks.

Therefore, traditional techniques based on deterministic Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) for the investment appraisal are not fully adequate to evaluate these risks and uncertainties and the investor's flexibility to deal with them. Hence, the literature recommends to assess the value of risks and uncertainties through the Real Option Analysis (ROA), which is a valuable method in uncertain contexts.

The economic valuation of large-scale applications (including pumped hydro storage and compressed air) considers benefits including: curtailment avoidance, grid congestion avoidance, price arbitrage and carbon-free energy delivery. In one technical assessment by the Carnegie Mellon Electricity Industry Centre, economic goals could be met using batteries if their capital cost was $30 to $50 per kilowatt-hour.

A metric of energy efficiency of storage is energy storage on energy invested (ESOI), which is the amount of energy that can be stored by a technology, divided by the amount of energy required to build that technology. The higher the ESOI, the better the storage technology is energetically. For lithium-ion batteries this is around 10, and for lead acid batteries it is about 2. Other forms of storage such as pumped hydroelectric storage generally have higher ESOI, such as 210.

Research

Germany

In 2013, the German Federal government allocated €200M (approximately US$270M) for research, and another €50M to subsidize battery storage in residential rooftop solar panels, according to a representative of the German Energy Storage Association.

Siemens AG commissioned a production-research plant to open in 2015 at the Zentrum für Sonnenenergie und Wasserstoff (ZSW, the German Center for Solar Energy and Hydrogen Research in the State of Baden-Württemberg), a university/industry collaboration in Stuttgart, Ulm and Widderstall, staffed by approximately 350 scientists, researchers, engineers, and technicians. The plant develops new near-production manufacturing materials and processes (NPMM&P) using a computerized Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) system. It aims to enable the expansion of rechargeable battery production with increased quality and lower cost.

United States

In 2014, research and test centers opened to evaluate energy storage technologies. Among them was the Advanced Systems Test Laboratory at the University of Wisconsin at Madison in Wisconsin State, which partnered with battery manufacturer Johnson Controls. The laboratory was created as part of the university's newly opened Wisconsin Energy Institute. Their goals include the evaluation of state-of-the-art and next generation electric vehicle batteries, including their use as grid supplements.

The State of New York unveiled its New York Battery and Energy Storage Technology (NY-BEST) Test and Commercialization Center at Eastman Business Park in Rochester, New York, at a cost of $23 million for its almost 1,700 m2 laboratory. The center includes the Center for Future Energy Systems, a collaboration between Cornell University of Ithaca, New York and the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. NY-BEST tests, validates and independently certifies diverse forms of energy storage intended for commercial use.

On September 27, 2017, Senators Al Franken of Minnesota and Martin Heinrich of New Mexico introduced Advancing Grid Storage Act (AGSA), which would devote more than $1 billion in research, technical assistance and grants to encourage energy storage in the United States.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, some 14 industry and government agencies allied with seven British universities in May 2014 to create the SUPERGEN Energy Storage Hub in order to assist in the coordination of energy storage technology research and development.