Theocracy is a form of government in which a deity of some type is recognized as the supreme ruling authority, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries that manage the day-to-day affairs of the government.

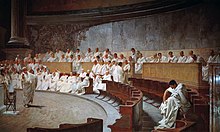

The Imperial cult of ancient Rome identified Roman emperors and some members of their families with the divinely sanctioned authority (auctoritas) of the Roman State. The official offer of cultus to a living emperor acknowledged his office and rule as divinely approved and constitutional: his Principate should therefore demonstrate pious respect for traditional Republican deities and mores.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates from the Greek θεοκρατία (theocratia) meaning "the rule of God". This in turn derives from θεός (theos), meaning "god", and κρατέω (krateo), meaning "to rule". Thus the meaning of the word in Greek was "rule by god(s)" or human incarnation(s) of god(s).

The term was initially coined by Flavius Josephus in the first century AD to describe the characteristic government of the Jews. Josephus argued that while mankind had developed many forms of rule, most could be subsumed under the following three types: monarchy, oligarchy, and democracy. However, according to Josephus, the government of the Jews was unique. Josephus offered the term "theocracy" to describe this polity, ordained by Moses, in which God is sovereign and his word is law.

Josephus' definition was widely accepted until the Enlightenment era, when the term took on negative connotations and was hardly salvaged by Hegel's abstruse commentary. The first recorded English use was in 1622, with the meaning "sacerdotal government under divine inspiration" (as in Biblical Israel before the rise of kings); the meaning "priestly or religious body wielding political and civil power" is recorded from 1825.

Synopsis

In some religions, the ruler, usually a king, was regarded as the chosen favorite of God (or gods) and could not be questioned, sometimes even being the descendant of or a god in their own right. Today, there is also a form of government where clerics have the power and the supreme leader could not be questioned in action. From the perspective of the theocratic government, "God himself is recognized as the head" of the state, hence the term theocracy, from the Koine Greek θεοκρατία "rule of God", a term used by Josephus for the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. Taken literally, theocracy means rule by God or gods and refers primarily to an internal "rule of the heart", especially in its biblical application. The common, generic use of the term, as defined above in terms of rule by a church or analogous religious leadership, would be more accurately described as an ecclesiocracy.

In a pure theocracy, the civil leader is believed to have a personal connection with the civilization's religion or belief. For example, Moses led the Israelites, and Muhammad led the early Muslims. There is a fine line between the tendency of appointing religious characters to run the state and having a religious-based government. According to the Holy Books, Prophet Joseph was offered an essential governmental role just because he was trustworthy, wise and knowledgeable (Quran 12: 54–55). As a result of the Prophet Joseph's knowledge and also due to his ethical and genuine efforts during a critical economic situation, the whole nation was rescued from a seven-year drought (Quran 12: 47–48).

When religions have a "holy book", it is used as a direct message from God. Law proclaimed by the ruler is also considered a divine revelation, and hence the law of God. As to the Prophet Muhammad ruling, "The first thirteen of the Prophet's twenty-three year career went on totally apolitical and non-violent. This attitude partly changed only after he had to flee from Mecca to Medina.This hijra, or migration, would be a turning point in the Prophet's mission and would mark the very beginning of the Muslim calendar. Yet the Prophet did not establish a theocracy in Medina. Instead of a polity defined solely by Islam, he founded a territorial polity based on religious pluralism. This is evident in a document called the ’Charter of Medina’, which the Prophet signed with the leaders of the other community in the city."

According to the Quran, Prophets were not after power or material resources. For example, in surah 26 verses (109, 127, 145, 164, 180), the Koran repeatedly quotes from Prophets Noah, Hud, Salih, Lut, and Shu'aib that: "I do not ask from you any payment for it; my payment is only from the Lord of the worlds." Also, in theocracy many aspects of the holy book are overshadowed by material powers. Due to being considered divine, the regime entitles itself to interpret verses to its own benefit and uses them out of context for its political aims. An ecclesiocracy, on the other hand, is a situation where the religious leaders assume a leading role in the state, but do not claim that they are instruments of divine revelation. For example, the prince-bishops of the European Middle Ages, where the bishop was also the temporal ruler. Such a state may use the administrative hierarchy of the religion for its own administration, or it may have two "arms" – administrators and clergy – but with the state administrative hierarchy subordinate to the religious hierarchy. The papacy in the Papal States occupied a middle ground between theocracy and ecclesiocracy, since the pope did not claim he was a prophet who received revelation from God and translated it into civil law.

Religiously endorsed monarchies fall between these two poles, according to the relative strengths of the religious and political organs.

Theocracy is distinguished from other, secular forms of government that have a state religion, or are influenced by theological or moral concepts, and monarchies held "By the Grace of God". In the most common usage of the term, some civil rulers are leaders of the dominant religion (e.g., the Byzantine emperor as patron and defender of the official Church); the government proclaims it rules on behalf of God or a higher power, as specified by the local religion, and with divine approval of government institutions and laws. These characteristics apply also to a caesaropapist regime. The Byzantine Empire however was not theocratic since the patriarch answered to the emperor, not vice versa; similarly in Tudor England the crown forced the church to break away from Rome so the royal (and, especially later, parliamentary) power could assume full control of the now Anglican hierarchy and confiscate most church property and income.

Secular governments can also co-exist with a state religion or delegate some aspects of civil law to religious communities. For example, in Israel marriage is governed by officially recognized religious bodies who each provide marriage services for their respected adherents, yet no form of civil marriage (free of religion, for atheists, for example) exists nor marriage by non-recognized minority religions.

Current theocracies

Christian theocracies

Holy See (Vatican City)

Following the Capture of Rome on 20 September 1870, the Papal States including Rome with the Vatican was annexed by the Kingdom of Italy. In 1929, through the Lateran Treaty signed with the Italian Government, the new state of Vatican City (population 842) – with no connection to the former Papal States – was formally created and recognized as an independent state. The head of state of the Vatican is the pope, elected by the College of Cardinals, an assembly of Senatorial-princes of the Church. They are usually clerics, appointed as Ordinaries, but in the past have also included men who were not bishops nor clerics. A pope is elected for life, and either dies or may resign. The cardinals are appointed by the popes, who thereby choose the electors of their successors.

Voting is limited to cardinals under 80 years of age. A Secretary for Relations with States, directly responsible for international relations, is appointed by the pope. The Vatican legal system is rooted in canon law but ultimately is decided by the pope; the Bishop of Rome as the Supreme Pontiff "has the fullness of legislative, executive and judicial powers." Although the laws of Vatican City come from the secular laws of Italy, under article 3 of the Law of the Sources of the Law, provision is made for the supplementary application of the "laws promulgated by the Kingdom of Italy". The government of the Vatican can also be considered an ecclesiocracy (ruled by the Church).

Mount Athos (Athonite State)

Mount Athos is a mountain peninsula in Greece which is an Eastern Orthodox autonomous region consisting of 20 monasteries under the direct jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. There have been almost 1,800-years of continuous Christian presence on Mount Athos and it has a long history of monastic traditions, which dates back to at least 800 A.D. The origins of self-rule are originally from an edict by the Byzantine Emperor Ioannis Tzimisces in 972, which was later reaffirmed by the Emperor Alexios I Komnenos in 1095. After Greece's independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1830, Greece claimed Mount Athos but after a diplomatic dispute with Russia the region was formally recognized as Greek after World War I.

Mount Athos is specifically exempt from the free movement of people and goods required by Greece's membership of the European Union and entrance is only allowed with express permission from the monks. The number of daily visitors to Mount Athos is restricted, with all visitors required to obtain an entrance permit. Only men are permitted to visit and Orthodox Christians take precedence in permit-issuing. Residents of Mount Athos must be men aged 18 and over who are members of the Eastern Orthodox Church and also either monks or workers.

Athos is governed jointly by a 'Holy Community' consisting of representatives from the 20 monasteries and a Civil Governor, appointed by the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Holy Community also has a four-member executive committee called the 'Holy Administration' which is led by a Protos.

Islamic theocracies

Iran

Iran has been described as a "theocratic republic" (by the CIA World Factbook), and its constitution has been described as a "hybrid" of "theocratic and democratic elements" by Francis Fukuyama. Like other Islamic states, it maintains religious laws and has religious courts to interpret all aspects of law. According to Iran's constitution, "all civil, penal, financial, economic, administrative, cultural, military, political, and other laws and regulations must be based on Islamic criteria."

In addition, Iran has a religious ruler and many religious officials in powerful government posts. The head of state, or "Supreme Leader", is a faqih (scholar of Islamic law) and possesses more power than Iran's president. The Leader appoints the heads of many powerful posts: the commanders of the armed forces, the director of the national radio and television network, the heads of the powerful major religious foundations, the chief justice, the attorney general (indirectly through the chief justice), special tribunals, and members of national security councils dealing with defence and foreign affairs. He also co-appoints the 12 jurists of the Guardian Council.

The Leader is elected by the Assembly of Experts which is made up of mujtahids, who are Islamic scholars competent in interpreting Sharia.

The Guardian Council, has the power to veto bills from majlis (parliament) and to approve or disapprove candidates who wish to run for high office (president, majlis, the Assembly of Experts). The council supervises elections, and can greenlight or ban investigations into the election process. Six of the Guardians (half the council) are faqih empowered to approve or veto all bills from the majlis (parliament) according to whether the faqih believe them to be in accordance with Islamic law and customs (Sharia). The other six members are lawyers appointed by the head of the judiciary (who is also a cleric and also appointed by the Leader).

An Islamic republic is the name given to several states that are officially ruled by Islamic laws, including the Islamic Republics of Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, and Mauritania. Pakistan first adopted the title under the constitution of 1956. Mauritania adopted it on 28 November 1958. Iran adopted it after the 1979 Iranian Revolution that overthrew the Pahlavi dynasty. Afghanistan adopted it in 2004 after the fall of the Taliban government. Despite having similar names, the countries differ greatly in their governments and laws.

The term "Islamic republic" has come to mean several different things, at times contradictory. To some Muslim religious leaders in the Middle East and Africa who advocate it, an Islamic republic is a state under a particular Islamic form of government. They see it as a compromise between a purely Islamic caliphate and secular nationalism and republicanism. In their conception of the Islamic republic, the penal code of the state is required to be compatible with some or all laws of Sharia, and the state may not be a monarchy, as many Middle Eastern states are presently.

Central Tibetan Administration

The Central Tibetan Administration, colloquially known as the Tibetan government in exile, is a Tibetan exile organisation with a state-like internal structure. According to its charter, the position of head of state of the Central Tibetan Administration belongs ex officio to the current Dalai Lama, a religious hierarch. In this respect, it continues the traditions of the former government of Tibet, which was ruled by the Dalai Lamas and their ministers, with a specific role reserved for a class of monk officials.

On 14 March 2011, at the 14th Dalai Lama's suggestion, the parliament of the Central Tibetan Administration began considering a proposal to remove the Dalai Lama's role as head of state in favor of an elected leader.

The first directly elected Kalön Tripa was Samdhong Rinpoche, who was elected on 20 August 2001.

Before 2011, the Kalön Tripa position was subordinate to the 14th Dalai Lama who presided over the government in exile from its founding. In August of that year, Lobsang Sangay polled 55 percent votes out of 49,189, defeating his nearest rival Tethong Tenzin Namgyal by 8,646 votes, becoming the second popularly elected Kalon Tripa. The Dalai Lama announced that his political authority would be transferred to Sangay.

Change to Sikyong

On 20 September 2012, the 15th Tibetan Parliament-in-Exile unanimously voted to change the title of Kalön Tripa to Sikyong in Article 19 of the Charter of the Tibetans in exile and relevant articles. The Dalai Lama had previously referred to the Kalon Tripa as Sikyong, and this usage was cited as the primary justification for the name change. According to Tibetan Review, "Sikyong" translates to "political leader", as distinct from "spiritual leader". Foreign affairs Kalon Dicki Chhoyang stated that the term "Sikyong" has had a precedent dating back to the 7th Dalai Lama, and that the name change "ensures historical continuity and legitimacy of the traditional leadership from the fifth Dalai Lama". The online Dharma Dictionary translates sikyong (srid skyong) as "secular ruler; regime, regent". The title sikyong had previously been used by regents who ruled Tibet during the Dalai Lama's minority.

States with official state religion

Having a state religion is not sufficient enough to be a theocracy in the narrow sense of the term. Many countries have a state religion without the government directly deriving its powers from a divine authority or a religious authority directly exercising governmental powers. Since the narrow sense of the term has few instances in the modern world, the more common usage of it is the wider sense of an enforced state religion.

Historic states with theocratic aspects

Ancient Egypt

The pharaoh was believed to be the offspring of the sungod Ra.

Japan

The emperor was historically venerated as the descendant of the Shinto sun goddess Amaterasu. Through this line of descent, the emperor was seen as a living god who was the supreme leader of the Japanese people. This status only changed with the Occupation of Japan following the end of the Second World War when Emperor Hirohito was forced to declare that he was not a living god in order for Japan to reorganize into a democratic nation.

Israel

Early Israel was a Kritarchy, ruled by Judges before instituting a monarchy. The Judges were believed to be representatives of YHVH Yahweh (also rendered as Jehovah).

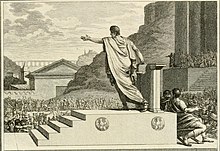

Western Antiquity

The imperial cults in Ancient Egypt and the Roman Empire, as well as numerous other monarchies, deified the ruling monarch. The state religion was often dedicated to the worship of the ruler as a deity, or the incarnation thereof.

In ancient and medieval Christianity, Caesaropapism is the doctrine where a head of state is at the same time the head of the church.

Tibet

Unified religious rule in Buddhist Tibet began in 1642, when the Fifth Dalai Lama allied with the military power of the Mongol Gushri Khan to consolidate the political power and center control around his office as head of the Gelug school. This form of government is known as the dual system of government. Prior to 1642, particular monasteries and monks had held considerable power throughout Tibet, but had not achieved anything approaching complete control, though power continued to be held in a diffuse, feudal system after the ascension of the Fifth Dalai Lama. Power in Tibet was held by a number of traditional elites, including members of the nobility, the heads of the major Buddhist sects (including their various tulkus), and various large and influential monastic communities.

The Bogd Khaanate period of Mongolia (1911–19) is also cited as a former Buddhist theocracy.

China

Similar to the Roman Emperor, the Chinese sovereign was historically held to be the Son of Heaven. However, from the first historical Emperor on, this was largely ceremonial and tradition quickly established it as a posthumous dignity, like the Roman institution. The situation before Qin Shi Huang Di is less clear.

The Shang dynasty essentially functioned as a theocracy, declaring the ruling family the sons of heaven and calling the chief sky god Shangdi after a word for their deceased ancestors. After their overthrow by the Zhou, the royal clan of Shang were not eliminated but instead moved to a ceremonial capital where they were charged to continue the performance of their rituals.

The titles combined by Shi Huangdi to form his new title of emperor were originally applied to god-like beings who ordered the heavens and earth and to culture heroes credited with the invention of agriculture, clothing, music, astrology, etc. Even after the fall of Qin, an emperor's words were considered sacred edicts (聖旨) and his written proclamations "directives from above" (上諭).

As a result, some Sinologists translate the title huangdi (usually rendered "emperor") as thearch. The term properly refers to the head of a thearchy (a kingdom of gods), but the more accurate "theocrat" carries associations of a strong priesthood that would be generally inaccurate in describing imperial China. Others reserve the use of "thearch" to describe the legendary figures of Chinese prehistory while continuing to use "emperor" to describe historical rulers.

The Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace in 1860s Qing China was a heterodox Christian theocracy led by a person who said that he was the younger brother of Jesus Christ, Hong Xiuquan. This theocratic state fought one of the most destructive wars in history, the Taiping Rebellion, against the Qing dynasty for fifteen years before being crushed following the fall of the rebel capital Nanjing.

Caliphate

The Sunni branch of Islam stipulates that, as a head of state, a Caliph should be elected by Muslims or their representatives. Followers of Shia Islam, however, believe a Caliph should be an Imam chosen by God from the Ahl al-Bayt (the "Family of the House", Muhammad's direct descendants).

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire (a.d. 324–1453) operated under caesaropapism, meaning that the emperor was both the head of civil society and the ultimate authority over the ecclesiastical authorities, or patriarchates. The emperor was considered to be God's omnipotent representative on earth and he ruled as an absolute autocrat.

Jennifer Fretland VanVoorst argues, “the Byzantine Empire became a theocracy in the sense that Christian values and ideals were the foundation of the empire's political ideals and heavily entwined with its political goals". Steven Runciman says in his book on The Byzantine Theocracy (2004):

The constitution of the Byzantine Empire was based on the conviction that it was the earthly copy of the Kingdom of Heaven. Just as God ruled in Heaven, so the Emperor, made in His image, should rule on earth and carry out his commandments. ...It saw itself as a universal empire. Ideally, it should embrace all the peoples of the Earth who, ideally, should all be members of the one true Christian Church, its own Orthodox Church. Just as man was made in God's image, so man's kingdom on Earth was made in the image of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Münster (16th Century)

Between 1533 and 1535 the Protestant leaders Jan Mattys and John of Leiden erected a short-living theocratic kingdom in the city of Münster. They created an anabaptist regime with chiliastic and milleniaristic expectations. Money was abolished and any violations of the Ten Commandments were punished by death. Despite the pietistic ideology, polygamy was allowed and von Leiden had 17 wives. In 1535, Münster was recaptured by Franz von Waldeck, ending the existence of the kingdom.

Geneva and Zurich (16th century)

Historians debate the extent to which Geneva, Switzerland, in the days of John Calvin (1509–64) was a theocracy. On the one hand, Calvin's theology clearly called for separation between church and state. Other historians have stressed the enormous political power wielded on a daily basis by the clerics.

In nearby Zurich, Switzerland, Protestant reformer Huldrych Zwingli (1484-1531) built a political system that many scholars have called a theocracy, while others have denied it.

Deseret (LDS Church, USA)

The question of theocracy has been debated extensively by historians regarding the Latter-Day Saint communities in Illinois, and especially in Utah.

Joseph Smith, mayor of Nauvoo, Illinois, and founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, ran as an independent for president in 1844. He proposed the redemption of slaves by selling public lands; reducing the size and salary of Congress; the closure of prisons; the annexation of Texas, Oregon, and parts of Canada; the securing of international rights on high seas; free trade; and the re-establishment of a national bank. His top aide Brigham Young campaigned for Smith saying, "He it is that God of Heaven designs to save this nation from destruction and preserve the Constitution." The campaign ended when Smith was killed by a mob while in the Carthage, Illinois, jail on June 27, 1844.

After severe persecution, the Mormons left the United States and resettled in a remote part of Utah, which was then part of Mexico. However the United States took control in 1848 and would not accept polygamy. The Mormon State of Deseret was short-lived. Its original borders stretched from western Colorado to the southern California coast. When the Mormons arrived in the valley of the Great Salt Lake in 1847, the Great Basin was still a part of Mexico and had no secular government. As a result, Brigham Young administered the region both spiritually and temporally through the highly organized and centralized Melchizedek Priesthood. This original organization was based upon a concept called theodemocracy, a governmental system combining Biblical theocracy with mid-19th-century American political ideals.

In 1849, the Saints organized a secular government in Utah, although many ecclesiastical leaders maintained their positions of secular power. The Mormons also petitioned Congress to have Deseret admitted into the Union as a state. However, under the Compromise of 1850, Utah Territory was created and Brigham Young was appointed governor. In this situation, Young still stood as head of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) as well as of Utah's secular government.

After the abortive Utah War of 1857–1858, the replacement of Young by an outside Federal Territorial Governor, intense federal prosecution of LDS Church leaders, the eventual resolution of controversies regarding plural marriage, and accession by Utah to statehood, the apparent temporal aspects of LDS theodemocracy receded markedly.

Persia/Iran

During the Achaemenid Empire, Zoroastrianism was the state religion and included formalized worship. The Persian kings were known to be pious Zoroastrians and they ruled with a Zoroastrian form of law called asha. However, Cyrus the Great, who founded the empire, avoided imposing the Zoroastrian faith on the inhabitants of conquered territory. Cyrus's kindness towards Jews has been cited as sparking Zoroastrian influence on Judaism.

Under the Seleucids, Zoroastrianism became autonomous. During the Sassanid period, the Zoroastrian calendar was reformed, image-use in worship was banned, Fire Temples were increasingly built, and intolerance towards other faiths prevailed.

Florence under Savonarola

The short reign (1494–1498) of Girolamo Savonarola, a Dominican priest, over the city of Florence had features of a theocracy. During his rule, "un-Christian" books, statues, poetry, and other items were burned (in the Bonfire of the Vanities), sodomy was made a capital offense, and other Christian practices became law.