| Scandinavia |

|---|

|

|

|

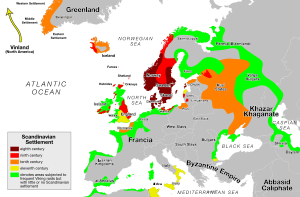

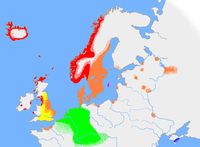

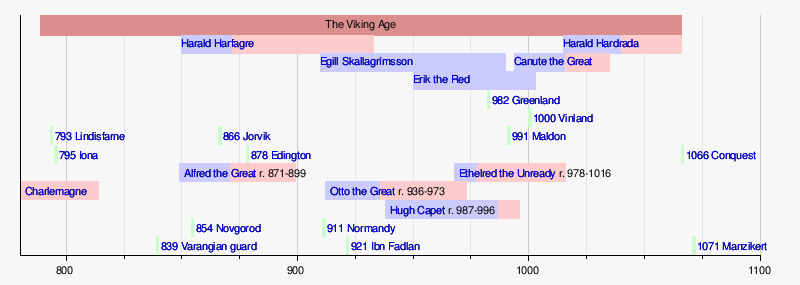

The Viking Age (793–1066 AD) was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonizing, conquest, and trading throughout Europe, and reached North America. It followed the Migration Period and the Germanic Iron Age. The Viking Age applies not only to their homeland of Scandinavia, but to any place significantly settled by Scandinavians during the period. The Scandinavians of the Viking Age are often referred to as Vikings as well as Norsemen, although few of them were Vikings in the technical sense.

Voyaging by sea from their homelands in Denmark, Norway and Sweden, the Norse people settled in the British Isles, Ireland, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, Normandy, the Baltic coast, and along the Dnieper and Volga trade routes in eastern Europe, where they were also known as Varangians. They also briefly settled in Newfoundland, becoming the first Europeans to reach North America. The Norse-Gaels, Normans, Rus' people, Faroese and Icelanders emerged from these Norse colonies. The Vikings founded several kingdoms and earldoms in Europe: the kingdom of the Isles (Suðreyjar), Orkney (Norðreyjar), York (Jórvík) and the Danelaw (Danalǫg), Dublin (Dyflin), Normandy, and Kievan Rus' (Garðaríki). The Norse homelands were also unified into larger kingdoms during the Viking Age, and the short-lived North Sea Empire included large swathes of Scandinavia and Britain. In 1021, the Vikings achieved the feat of reaching North America- the date of which was not specified until exactly a millennium later.

Several things drove this expansion. The Vikings were drawn by the growth of wealthy towns and monasteries overseas, and weak kingdoms. They may also have been pushed to leave their homeland by overpopulation, lack of good farmland, and political strife arising from the unification of Norway. The aggressive expansion of the Carolingian Empire and forced conversion of the neighboring Saxons to Christianity may also have been a factor. Sailing innovations had allowed the Vikings to sail further and longer to begin with.

Information about the Viking Age is drawn largely from primary sources written by those the Vikings encountered, as well as archaeology, supplemented with secondary sources such as the Icelandic Sagas.

Historical context

In England, the Viking attack of 8 June 793 that destroyed the abbey on Lindisfarne, a centre of learning on an island off the northeast coast of England in Northumberland, is regarded as the beginning of the Viking Age. Judith Jesch has argued that the start of the Viking Age can be pushed back to 700–750, as it was unlikely that the Lindisfarne attack was the first attack and given archeological evidence that suggests contacts between Scandinavia and the British isles earlier in the century. The earliest raids were most likely small in scale, but expanded in scale during the 9th century.

In the Lindisfarne attack, monks were killed in the abbey, thrown into the sea to drown, or carried away as slaves along with the church treasures, giving rise to the traditional (but unattested) prayer—A furore Normannorum libera nos, Domine, "Free us from the fury of the Northmen, Lord." Three Viking ships had beached in Weymouth Bay four years earlier (although due to a scribal error the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle dates this event to 787 rather than 789), but that incursion may have been a trading expedition that went wrong rather than a piratical raid. Lindisfarne was different. The Viking devastation of Northumbria's Holy Island was reported by the Northumbrian scholar Alcuin of York, who wrote: "Never before in Britain has such a terror appeared". Vikings were portrayed as wholly violent and bloodthirsty by their enemies. In medieval English chronicles, they are described as "wolves among sheep".

The first challenges to the many anti-Viking images in Britain emerged in the 17th century. Pioneering scholarly works on the Viking Age reached a small readership in Britain. Linguistics traced the Viking Age origins of rural idioms and proverbs. New dictionaries of the Old Norse language enabled more Victorians to read the Icelandic Sagas.

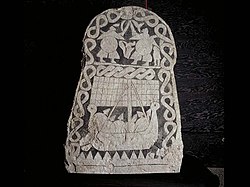

In Scandinavia, the 17th-century Danish scholars Thomas Bartholin and Ole Worm and Swedish scholar Olaus Rudbeck were the first to use runic inscriptions and Icelandic Sagas as primary historical sources. During the Enlightenment and Nordic Renaissance, historians such as the Icelandic-Norwegian Thormodus Torfæus, Danish-Norwegian Ludvig Holberg, and Swedish Olof von Dalin developed a more "rational" and "pragmatic" approach to historical scholarship.

By the latter half of the 18th century, while the Icelandic sagas were still used as important historical sources, the Viking Age had again come to be regarded as a barbaric and uncivilised period in the history of the Nordic countries.

Scholars outside Scandinavia did not begin to extensively reassess the achievements of the Vikings until the 1890s, recognising their artistry, technological skills, and seamanship.

Until recently, the history of the Viking Age had largely been based on Icelandic Sagas, the history of the Danes written by Saxo Grammaticus, the Kievan Rus's Primary Chronicle, and Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib. Today, most scholars take these texts as sources not to be understood literally and are relying more on concrete archaeological findings, numismatics, and other direct scientific disciplines and methods.

Historical background

The Vikings who invaded western and eastern Europe were mainly pagans from the same area as present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. They also settled in the Faroe Islands, Ireland, Iceland, peripheral Scotland (Caithness, the Hebrides and the Northern Isles), Greenland, and Canada.

Their North Germanic language, Old Norse, became the mother-tongue of present-day Scandinavian languages. By 801, a strong central authority appears to have been established in Jutland, and the Danes were beginning to look beyond their own territory for land, trade, and plunder.

In Norway, mountainous terrain and fjords formed strong natural boundaries. Communities remained independent of each other, unlike the situation in lowland Denmark. By 800, some 30 small kingdoms existed in Norway.

The sea was the easiest way of communication between the Norwegian kingdoms and the outside world. In the eighth century, Scandinavians began to build ships of war and send them on raiding expeditions which started the Viking Age. The North Sea rovers were traders, colonisers, explorers, and plunderers.

Probable causes of Norse expansion

| Norse people |

|---|

|

Many theories are posited for the cause of the Viking invasions; the will to explore likely played a major role. At the time, England, Wales, and Ireland were vulnerable to attack, being divided into many different warring kingdoms in a state of internal disarray, while the Franks were well defended. Overpopulation, especially near the Scandes, was possibly influential (this theory regarding overpopulation is disputed). Technological advances like the use of iron and a shortage of women due to selective female infanticide also likely had an impact. Tensions caused by Frankish expansion to the south of Scandinavia, and their subsequent attacks upon the Viking peoples, may have also played a role in Viking pillaging. Harald I of Norway ("Harald Fairhair") had united Norway around this time and displaced many peoples. As a result, these people sought for new bases to launch counter-raids against Harald.

Debate among scholars is ongoing as to why the Scandinavians began to expand from the eighth through 11th centuries. Various factors have been highlighted: demographic, economic, ideological, political, technological, and environmental.

- Demographic model

- This model suggests that Scandinavia experienced a population boom just before the Viking Age began. The agricultural capacity of the land was not enough to keep up with the increasing population. As a result, many Scandinavians found themselves with no property and no status. To remedy this, these landless men took to piracy to obtain material wealth. The population continued to grow, and the pirates looked further and further beyond the borders of the Baltic, and eventually into all of Europe.

- Economic model

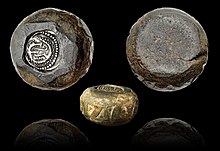

- The economic model states that the Viking Age was the result of growing urbanism and trade throughout mainland Europe. As the Islamic world grew, so did its trade routes, and the wealth which moved along them was pushed further and further north. In Western Europe, proto-urban centres such as the -wich towns of Anglo-Saxon England began to boom during the prosperous era known as the "Long Eighth Century". The Scandinavians, like many other Europeans, were drawn to these wealthier "urban" centres, which soon became frequent targets of Viking raids. The connection of the Scandinavians to larger and richer trade networks lured the Vikings into Western Europe, and soon the rest of Europe and parts of the Middle East. In England, hoards of Viking silver, such as the Cuerdale Hoard and the Vale of York Hoard, offer good insight to this phenomenon. Critics of this model argue that the earliest recorded Viking raids were in Western Norway and northern Britain, which were not highly economically integrated areas. Alternative versions of the economic model point to economic incentives that stemmed from youth bulges, as young men were driven to maritime activity due to limited economic alternatives.

- Ideological model

- This era coincided with the Medieval Warm Period (800–1300) and stopped with the start of the Little Ice Age (about 1250–1850). The start of the Viking Age, with the sack of Lindisfarne, also coincided with Charlemagne's Saxon Wars, or Christian wars with pagans in Saxony. Bruno Dumézil theorises that the Viking attacks may have been in response to the spread of Christianity among pagan peoples. Because of the penetration of Christianity in Scandinavia, serious conflict divided Norway for almost a century.

- Political model

- The first of two main components to the political model is the external "Pull" factor, which suggests that the weak political bodies of Britain and Western Europe made for an attractive target for Viking raiders. The reasons for these weaknesses vary, but generally can be simplified into decentralized polities, or religious sites. As a result, Viking raiders found it easy to sack and then retreat from these areas which were thus frequently raided. The second case is the internal "Push" factor, which coincides with a period just before the Viking Age in which Scandinavia was undergoing a mass centralization of power in the modern-day countries of Denmark, Sweden, and especially Norway. This centralization of power forced hundreds of chieftains from their lands, which were slowly being eaten up by the kings and dynasties that began to emerge. As a result, many of these chiefs sought refuge elsewhere, and began harrying the coasts of the British Isles and Western Europe.

- Technological model

- This model suggests that the Viking Age occurred as a result of technological innovations that allowed the Vikings to go on their raids in the first place. There is no doubt that piracy existed in the Baltic before the Viking Age, but developments in sailing technology and practice made it possible for early Viking raiders to attack lands farther away. Among these developments are included the use of larger sails, tacking practices, and 24-hour sailing.

These models constitute much of what is known about the motivations for and the causes of the Viking Age. In all likelihood, the beginning of this age was the result of some combination of the aforementioned models.

The Viking colonization of islands in the North Atlantic has in part been attributed to a period of favorable climate (the Medieval Climactic Optimum), as the weather was relatively stable and predictable, with calm seas. Sea ice was rare, harvests were typically strong, and fishing conditions were good.

Historic overview

The earliest date given for a Viking raid is 789, when according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a group of Danes sailed to the Isle of Portland in Dorset (it was wrongly recorded as 787). They were mistaken for merchants by a royal official. When asked to come to the king's manor to pay a trading tax on their goods, they murdered the official. The beginning of the Viking Age in the British Isles is often set at 793. It was recorded in the Anglo–Saxon Chronicle that the Northmen raided the important island monastery of Lindisfarne (the generally accepted date is actually 8 June, not January):

A.D. 793. This year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying across the firmament. These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great famine: and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January in the same year, the harrowing inroads of heathen men made lamentable havoc in the church of God in Holy-island (Lindisfarne), by rapine and slaughter.

— Anglo Saxon Chronicle.

In 794, according to the Annals of Ulster, a serious attack was made on Lindisfarne's mother-house of Iona, which was followed in 795 by raids upon the northern coast of Ireland. From bases there, the Norsemen attacked Iona again in 802, causing great slaughter amongst the Céli Dé Brethren, and burning the abbey to the ground.

The Vikings primarily targeted Ireland until 830, as England and the Carolingian Empire was able to fight the Vikings off. However, after 830, the Vikings had considerable success against England, Carolingian Empire and other parts of Western Europe. After 830, the Vikings exploited disunity within the Carolingian Empire, as well as pitted the English kingdoms against each other.

The Kingdom of the Franks under Charlemagne was particularly devastated by these raiders, who could sail up the Seine with near impunity. Near the end of Charlemagne's reign (and throughout the reigns of his sons and grandsons), a string of Norse raids began, culminating in a gradual Scandinavian conquest and settlement of the region now known as Normandy in 911. French King Charles the Simple granted the Duchy of Normandy to Viking warleader Rollo (a chieftain of disputed Norwegian or Danish origins) in order to stave off attacks by other Vikings. Charles gave Rollo the title of duke. In return, Rollo swore fealty to Charles, converted to Christianity, and undertook to defend the northern region of France against the incursions of other Viking groups. Several generations later, the Norman descendants of these Viking settlers not only identified themselves as Norman, but also carried the Norman language (either a French dialect or a Romance language which can be classified as one of the Oïl languages along with French, Picard and Walloon), and their Norman culture, into England in 1066. With the Norman Conquest, they became the ruling aristocracy of Anglo–Saxon England.

The clinker-built longships used by the Scandinavians were uniquely suited to both deep and shallow waters. They extended the reach of Norse raiders, traders, and settlers along coastlines and along the major river valleys of north-western Europe. Rurik also expanded to the east, and in 859 became ruler either by conquest or invitation by local people of the city of Novgorod (which means "new city") on the Volkhov River. His successors moved further, founding the early East Slavic state of Kievan Rus' with the capital in Kiev. This persisted until 1240, when the Mongols invaded Kievan Rus'.

Other Norse people continued south to the Black Sea and then on to Constantinople. Whenever these Viking ships ran aground in shallow waters, the Vikings reportedly turned them on their sides and dragged them across the shallows into deeper waters. The eastern connections of these "Varangians" brought Byzantine silk, a cowrie shell from the Red Sea, and even coins from Samarkand, to Viking York.

In 884, an army of Danish Vikings was defeated at the Battle of Norditi (also called the Battle of Hilgenried Bay) on the Germanic North Sea coast by a Frisian army under Archbishop Rimbert of Bremen-Hamburg, which precipitated the complete and permanent withdrawal of the Vikings from East Frisia. In the 10th and 11th centuries, Saxons and Slavs began to use trained mobile cavalry successfully against Viking foot soldiers, making it hard for Viking invaders to fight inland.

In Scandinavia, the Viking Age is considered to have ended with the establishment of royal authority in the Scandinavian countries and the establishment of Christianity as the dominant religion. The date is usually put somewhere in the early 11th century in all three Scandinavian countries. The end of the Viking era in Norway is marked by the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030. Although Olafr Haraldsson's (later known as Olav the Holy) army lost the battle, Christianity spread, partly on the strength of rumours of miraculous signs after his death. Norwegians would no longer be called Vikings. In Sweden, the reign of king Olov Skötkonung (c. 995–1020) is considered to be the transition from the Viking Age to the Middle Ages, because he was the first Christian king of the Swedes, and he is associated with a growing influence of the church in what is today southwestern and central Sweden. Norse beliefs persisted until the 12th century. Olof being the last king in Scandinavia to adopt a Christianity marked a definite end to the Viking Age.

Scholars have proposed different end dates for the Viking Age, but most argue it ended in the 11th century. The year 1000 is sometimes used, as that was the year in which Iceland converted to Christianity, marking the conversion of all of Scandinavia to Christianity. The death of Harthacnut, the Danish King of England, in 1042 has also been used as an end date. The end of the Viking Age is traditionally marked in England by the failed invasion attempted by the Norwegian king Harald III (Haraldr Harðráði), who was defeated by Saxon King Harold Godwinson in 1066 at the Battle of Stamford Bridge; in Ireland, the capture of Dublin by Strongbow and his Hiberno-Norman forces in 1171; and 1263 in Scotland by the defeat of King Hákon Hákonarson at the Battle of Largs by troops loyal to Alexander III. Godwinson was subsequently defeated within a month by another Viking descendant, William, Duke of Normandy. Scotland took its present form when it regained territory from the Norse between the 13th and the 15th centuries; the Western Isles and the Isle of Man remained under Scandinavian authority until 1266. Orkney and Shetland belonged to the king of Norway as late as 1469. Consequently, a "long Viking Age" may stretch into the 15th century.

Northwestern Europe

England

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, Viking raiders struck England in 793 and raided Lindisfarne, the monastery that held Saint Cuthbert's relics, killing the monks and capturing the valuables. The raid marked the beginning of the "Viking Age of Invasion". Great but sporadic violence continued on England's northern and eastern shores, with raids continuing on a small scale across coastal England. While the initial raiding groups were small, a great amount of planning is believed to have been involved. The Vikings raided during the winter of 840–841, rather than the usual summer, having waited on an island off Ireland.

In 850, the Vikings overwintered for the first time in England, on the island of Thanet, Kent. In 854, a raiding party overwintered a second time, at the Isle of Sheppey in the Thames estuary. In 864, they reverted to Thanet for their winter encampment.

The following year, the Great Heathen Army, led by brothers Ivar the Boneless (Halfdan and Ubba), and also by another Viking Guthrum, arrived in East Anglia. They proceeded to cross England into Northumbria and captured York, establishing a Viking community in Jorvik, where some settled as farmers and craftsmen. Most of the English kingdoms, being in turmoil, could not stand against the Vikings. In 867, Northumbria became the northern kingdom of the coalescing Danelaw, after its conquest by the Ragnarsson brothers, who installed an Englishman, Ecgberht, as a puppet king. By 870, the "Great Summer Army" arrived in England, led by a Viking leader called Bagsecg and his five earls. Aided by the Great Heathen Army (which had already overrun much of England from its base in Jorvik), Bagsecg's forces, and Halfdan's forces (through an alliance), the combined Viking forces raided much of England until 871, when they planned an invasion of Wessex. On 8 January 871, Bagsecg was killed at the Battle of Ashdown along with his earls. As a result, many of the Vikings returned to northern England, where Jorvic had become the centre of the Viking kingdom, but Alfred of Wessex managed to keep them out of his country. Alfred and his successors continued to drive back the Viking frontier and take York. A new wave of Vikings appeared in England in 947, when Eric Bloodaxe captured York.

In 1003, the Danish King Sweyn Forkbeard started a series of raids against England to avenge the St. Brice's Day massacre of England's Danish inhabitants, culminating in a full-scale invasion that led to Sweyn being crowned king of England in 1013. Sweyn was also king of Denmark and parts of Norway at this time. The throne of England passed to Edmund Ironside of Wessex after Sweyn's death in 1014. Sweyn's son, Cnut the Great, won the throne of England in 1016 through conquest. When Cnut the Great died in 1035 he was a king of Denmark, England, Norway, and parts of Sweden. Harold Harefoot became king of England after Cnut's death, and Viking rule of England ceased.

The Viking presence declined until 1066, when they lost their final battle with the English at Stamford Bridge. The death in the battle of King Harald Hardrada of Norway ended any hope of reviving Cnut's North Sea Empire, and it is because of this, rather than the Norman conquest, that 1066 is often taken as the end of the Viking Age. Nineteen days later, a large army containing and led by senior Normans, themselves mostly male-line descendants of Norsemen, invaded England and defeated the weakened English army at the Battle of Hastings. The army invited others from across Norman gentry and ecclesiastical society to join them. There were several unsuccessful attempts by Scandinavian kings to regain control of England, the last of which took place in 1086.

In 1152, Eystein II of Norway led a plundering raid down the east coast of Britain.

Ireland

In 795, small bands of Vikings began plundering monastic settlements along the coast of Gaelic Ireland. The Annals of Ulster state that in 821 the Vikings plundered Howth and "carried off a great number of women into captivity". From 840 the Vikings began building fortified encampments, longphorts, on the coast and overwintering in Ireland. The first were at Dublin and Linn Duachaill. Their attacks became bigger and reached further inland, striking larger monastic settlements such as Armagh, Clonmacnoise, Glendalough, Kells and Kildare, and also plundering the ancient tombs of Brú na Bóinne. Viking chief Thorgest is said to have raided the whole midlands of Ireland until he was killed by Máel Sechnaill I in 845.

In 853, Viking leader Amlaíb (Olaf) became the first king of Dublin. He ruled along with his brothers Ímar (possibly Ivar the Boneless) and Auisle. Over the following decades, there was regular warfare between the Vikings and the Irish, and between two groups of Vikings: the Dubgaill and Finngaill (dark and fair foreigners). The Vikings also briefly allied with various Irish kings against their rivals. In 866, Áed Findliath burnt all Viking longphorts in the north, and they never managed to establish permanent settlements in that region. The Vikings were driven from Dublin in 902.

They returned in 914, now led by the Uí Ímair (House of Ivar). During the next eight years the Vikings won decisive battles against the Irish, regained control of Dublin, and founded settlements at Waterford, Wexford, Cork and Limerick, which became Ireland's first large towns. They were important trading hubs, and Viking Dublin was the biggest slave port in western Europe.

These Viking territories became part of the patchwork of kingdoms in Ireland. Vikings intermarried with the Irish and adopted elements of Irish culture, becoming the Norse-Gaels. Some Viking kings of Dublin also ruled the kingdom of the Isles and York; such as Sitric Cáech, Gofraid ua Ímair, Olaf Guthfrithson and Olaf Cuaran. Sigtrygg Silkbeard was "a patron of the arts, a benefactor of the church, and an economic innovator" who established Ireland's first mint, in Dublin.

In 980, Máel Sechnaill Mór defeated the Dublin Vikings and forced them into submission. Over the following thirty years, Brian Boru subdued the Viking territories and made himself High King of Ireland. The Dublin Vikings, together with Leinster, twice rebelled against him, but they were defeated in the battles of Glenmama (999) and Clontarf (1014). After the battle of Clontarf, the Dublin Vikings could no longer "single-handedly threaten the power of the most powerful kings of Ireland". Brian's rise to power and conflict with the Vikings is chronicled in Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib ("The War of the Irish with the Foreigners").

Scotland

While few records are known, the Vikings are thought to have led their first raids in Scotland on the holy island of Iona in 794, the year following the raid on the other holy island of Lindisfarne, Northumbria.

In 839, a large Norse fleet invaded via the River Tay and River Earn, both of which were highly navigable, and reached into the heart of the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu. They defeated Eogán mac Óengusa, king of the Picts, his brother Bran, and the king of the Scots of Dál Riata, Áed mac Boanta, along with many members of the Pictish aristocracy in battle. The sophisticated kingdom that had been built fell apart, as did the Pictish leadership, which had been stable for more than 100 years since the time of Óengus mac Fergusa (The accession of Cináed mac Ailpín as king of both Picts and Scots can be attributed to the aftermath of this event).

In 870, the Britons of the Old North around the Firth of Clyde came under Viking attack as well. The fortress atop Alt Clut ("Rock of the Clyde," the Brythonic name for Dumbarton Rock, which had become the metonym for their kingdom) was besieged by the Viking kings Amlaíb and Ímar. After four months, its water supply failed, and the fortress fell. The Vikings are recorded to have transported a vast prey of British, Pictish, and English captives back to Ireland. These prisoners may have included the ruling family of Alt Clut including the king Arthgal ap Dyfnwal, who was slain the following year under uncertain circumstances. The fall of Alt Clut marked a watershed in the history of the realm. Afterwards, the capital of the restructured kingdom was relocated about 12 miles (20 km) up the River Clyde to the vicinity of Govan and Partick (within present-day Glasgow), and became known as the Kingdom of Strathclyde, which persisted as a major regional political player for another 150 years.

The land that now comprises most of the Scottish Lowlands had previously been the northernmost part of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria, which fell apart with its Viking conquest; these lands were never regained by the Anglo-Saxons, or England. The upheaval and pressure of Viking raiding, occupation, conquest and settlement resulted in alliances among the formerly enemy peoples that comprised what would become present-day Scotland. Over the subsequent 300 years, this Viking upheaval and pressure led to the unification of the previously contending Gaelic, Pictish, British, and English kingdoms, first into the Kingdom of Alba, and finally into the greater Kingdom of Scotland. The Viking Age in Scotland came to an end after another 100 years. The last vestiges of Norse power in the Scottish seas and islands were completely relinquished after another 200 years.

Earldom of Orkney

By the mid-9th century, the Norsemen had settled in Shetland, Orkney (the Nordreys- Norðreyjar), the Hebrides and Isle of Man, (the Sudreys- Suðreyjar—this survives in the Diocese of Sodor and Man) and parts of mainland Scotland. The Norse settlers were to some extent integrating with the local Gaelic population (see Norse-Gaels) in the Hebrides and Man. These areas were ruled over by local Jarls, originally captains of ships or hersirs. The Jarl of Orkney and Shetland, however, claimed supremacy.

In 875, King Harald Fairhair led a fleet from Norway to Scotland. In his attempt to unite Norway, he found that many of those opposed to his rise to power had taken refuge in the Isles. From here, they were raiding not only foreign lands but were also attacking Norway itself. He organised a fleet and was able to subdue the rebels, and in doing so brought the independent Jarls under his control, many of the rebels having fled to Iceland. He found himself ruling not only Norway, but also the Isles, Man, and parts of Scotland.

Kings of the Isles

In 876, the Norse-Gaels of Mann and the Hebrides rebelled against Harald. A fleet was sent against them led by Ketil Flatnose to regain control. On his success, Ketil was to rule the Sudreys as a vassal of King Harald. His grandson, Thorstein the Red, and Sigurd the Mighty, Jarl of Orkney, invaded Scotland and were able to exact tribute from nearly half the kingdom until their deaths in battle. Ketil declared himself King of the Isles. Ketil was eventually outlawed and, fearing the bounty on his head, fled to Iceland.

The Norse-Gaelic Kings of the Isles continued to act semi independently, in 973 forming a defensive pact with the Kings of Scotland and Strathclyde. In 1095, the King of Mann and the Isles Godred Crovan was killed by Magnus Barelegs, King of Norway. Magnus and King Edgar of Scotland agreed on a treaty. The islands would be controlled by Norway, but mainland territories would go to Scotland. The King of Norway nominally continued to be king of the Isles and Man. However, in 1156, The kingdom was split into two. The Western Isles and Man continued as to be called the "Kingdom of Man and the Isles", but the Inner Hebrides came under the influence of Somerled, a Gaelic speaker, who was styled 'King of the Hebrides'. His kingdom was to develop latterly into the Lordship of the Isles.

In eastern Aberdeenshire, the Danes invaded at least as far north as the area near Cruden Bay.

The Jarls of Orkney continued to rule much of northern Scotland until 1196, when Harald Maddadsson agreed to pay tribute to William the Lion, King of Scots, for his territories on the mainland.

The end of the Viking Age proper in Scotland is generally considered to be in 1266. In 1263, King Haakon IV of Norway, in retaliation for a Scots expedition to Skye, arrived on the west coast with a fleet from Norway and Orkney. His fleet linked up with those of King Magnus of Man and King Dougal of the Hebrides. After peace talks failed, his forces met with the Scots at Largs, in Ayrshire. The battle proved indecisive, but it did ensure that the Norse were not able to mount a further attack that year. Haakon died overwintering in Orkney, and by 1266, his son Magnus the Law-mender ceded the Kingdom of Man and the Isles, with all territories on mainland Scotland to Alexander III, through the Treaty of Perth.

Orkney and Shetland continued to be ruled as autonomous Jarldoms under Norway until 1468, when King Christian I pledged them as security on the dowry of his daughter, who was betrothed to James III of Scotland. Although attempts were made during the 17th and 18th centuries to redeem Shetland, without success, and Charles II ratifying the pawning in the 1669 Act for annexation of Orkney and Shetland to the Crown, explicitly exempting them from any "dissolution of His Majesty's lands", they are currently considered as being officially part of the United Kingdom.

Wales

Incursions in Wales were decisively reversed at the Battle of Buttington in Powys, 893, when a combined Welsh and Mercian army under Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians, defeated a Danish band.

Wales was not colonised by the Vikings as heavily as eastern England. The Vikings did, however, settle in the south around St. David's, Haverfordwest, and Gower, among other places. Place names such as Skokholm, Skomer, and Swansea remain as evidence of the Norse settlement. The Vikings, however, did not subdue the Welsh mountain kingdoms.

Iceland

According to Sagas, Iceland was discovered by Naddodd, a Viking from the Faroe Islands, after which it was settled by mostly Norwegians fleeing the oppressive rule of Harald Fairhair in 985. While harsh, the land allowed for a pastoral farming life familiar to the Norse. According to the saga of Erik the Red, when Erik was exiled from Iceland, he sailed west and pioneered Greenland.

Kvenland

Kvenland, known as Cwenland, Kænland, and similar terms in medieval sources, is an ancient name for an area in Scandinavia and Fennoscandia. A contemporary reference to Kvenland is provided in an Old English account written in the 9th century. It used the information provided by the Norwegian adventurer and traveller named Ohthere. Kvenland, in that or close to that spelling, is also known from Nordic sources, primarily Icelandic, but also one that was possibly written in the modern-day area of Norway.

All the remaining Nordic sources discussing Kvenland, using that or close to that spelling, date to the 12th and 13th centuries, but some of them—in part at least—are believed to be rewrites of older texts. Other references and possible references to Kvenland by other names and/or spellings are discussed in the main article of Kvenland.

Northern Europe

Estonia

Estonia during Viking Age was a Finnic area divided between two major cultural regions, a coastal and an inland one, corresponding to the historical cultural and linguistic division between Northern and Southern Estonian. These two areas were further divided between loosely allied regions. The Viking Age in Estonia is considered to be part of the Iron Age period which started around 400 AD and ended around 1200 AD, soon after Estonian raiders were recorded in the Eric Chronicle to have sacked Sigtuna in 1187.

The society, economy, settlement and culture of the territory of what is in the present-day the country of Estonia is studied mainly through archaeological sources. The era is seen to have been a period of rapid change. The Estonian peasant culture came into existence by the end of the Viking Age. The overall understanding of the Viking Age in Estonia is deemed to be fragmentary and superficial, because of the limited amount of surviving source material. The main sources for understanding the period are remains of the farms and fortresses of the era, cemeteries and a large amount of excavated objects.

The landscape of Ancient Estonia featured numerous hillforts, some later hillforts on Saaremaa heavily fortified during the Viking Age and on to the 12th century. There were a number of late prehistoric or medieval harbour sites on the coast of Saaremaa, but none have been found that are large enough to be international trade centres. The Estonian islands also have a number of graves from the Viking Age, both individual and collective, with weapons and jewellery. Weapons found in Estonian Viking Age graves are common to types found throughout Northern Europe and Scandinavia.

Curonians

The Curonians were known as fierce warriors, excellent sailors and pirates. They were involved in several wars and alliances with Swedish, Danish and Icelandic Vikings.

In c. 750, according to Norna-Gests þáttr saga from c. 1157, Sigurd Ring, a legendary king of Denmark and Sweden, fought against the invading Curonians and Kvens (Kvænir) in the southern part of what today is Sweden:

- "Sigurd Ring (Sigurðr) was not there, since he had to defend his land, Sweden (Svíþjóð), since Curonians (Kúrir) and Kvænir were raiding there."

Curonians are mentioned among other participants of the Battle of Brávellir.

Grobin (Grobiņa) was the main centre of the Curonians during the Vendel Age. Chapter 46 of Egils Saga describes one Viking expedition by the Vikings Thorolf and Egill Skallagrímsson in Courland. According to some opinions, they took part in attacking Sweden's main city Sigtuna in 1187. Curonians established temporary settlements near Riga and in overseas regions including eastern Sweden and the islands of Gotland and Bornholm.

Eastern Europe

The Varangians or Varyags were Scandinavians, often Swedes, who migrated eastwards and southwards through what is now Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine mainly in the 9th and 10th centuries. Engaging in trade, piracy, and mercenary activities, they roamed the river systems and portages of Gardariki, reaching the Caspian Sea and Constantinople. Contemporary English publications also use the name "Viking" for early Varangians in some contexts.

The term Varangian remained in usage in the Byzantine Empire until the 13th century, largely disconnected from its Scandinavian roots by then. Having settled Aldeigja (Ladoga) in the 750s, Scandinavian colonists were probably an element in the early ethnogenesis of the Rus' people, and likely played a role in the formation of the Rus' Khaganate. The Varangians are first mentioned by the Primary Chronicle as having exacted tribute from the Slavic and Finnic tribes in 859. It was the time of rapid expansion of the Vikings in Northern Europe; England began to pay Danegeld in 859, and the Curonians of Grobin faced an invasion by the Swedes at about the same date.

In 862, the Finnic and Slavic tribes rebelled against the Varangian Rus, driving them overseas back to Scandinavia, but soon started to conflict with each other. The disorder prompted the tribes to invite back the Varangian Rus "to come and rule them" and bring peace to the region. This was a somewhat bilateral relation with the Varagians defending the cities that they ruled. Led by Rurik and his brothers Truvor and Sineus, the invited Varangians (called Rus') settled around the town of Novgorod (Holmgard).

In the 9th century, the Rus' operated the Volga trade route, which connected Northern Russia (Gardariki) with the Middle East (Serkland). As the Volga route declined by the end of the century, the Trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks rapidly overtook it in popularity. Apart from Ladoga and Novgorod, Gnezdovo and Gotland were major centres for Varangian trade.

The scholarly consensus is that the Rus' people originated in what is currently coastal eastern Sweden around the eighth century and that their name has the same origin as Roslagen in Sweden (with the older name being Roden). According to the prevalent theory, the name Rus', like the Proto-Finnic name for Sweden (*Ruotsi), is derived from an Old Norse term for "the men who row" (rods-) as rowing was the main method of navigating the rivers of Eastern Europe, and that it could be linked to the Swedish coastal area of Roslagen (Rus-law) or Roden, as it was known in earlier times. The name Rus' would then have the same origin as the Finnish and Estonian names for Sweden: Ruotsi and Rootsi. The term "Varangian" became more common from the 11th century onwards.

In these years, Swedish men left to enlist in the Byzantine Varangian Guard in such numbers that a medieval Swedish law, Västgötalagen, from Västergötland declared no one could inherit while staying in "Greece"—the then Scandinavian term for the Byzantine Empire—to stop the emigration, especially as two other European courts simultaneously also recruited Scandinavians: Kievan Rus' c. 980–1060 and London 1018–1066 (the Þingalið).

In contrast to the intense Scandinavian influence in Normandy and the British Isles, Varangian culture did not survive to a great extent in the East. Instead, the Varangian ruling classes of the two powerful city-states of Novgorod and Kiev were thoroughly Slavicised by the beginning of the 11th century. Old Norse was spoken in one district of Novgorod, however, until the 13th century.

Central Europe

Viking Age Scandinavian settlements were set up along the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, primarily for trade purposes. Their appearance coincides with the settlement and consolidation of the Slavic tribes in the respective areas. Scandinavians had contacts to the Slavs since their initial immigration, which were soon followed by both the construction of Scandinavian emporia and Slavic burghs in their vicinity. The Scandinavian settlements were larger than the early Slavic ones, their craftsmen had a considerably higher productivity, and, in contrast to the early Slavs, the Scandinavians were capable of seafaring. Their importance for trade with the Slavic world, however, was limited to the coastal regions and their hinterlands.

Scandinavian settlements on the Mecklenburgian coast include Reric (Groß Strömkendorf) on the eastern coast of Wismar Bay, and Dierkow (near Rostock). Reric was set up around the year 700, but following later warfare between Obodrites and Danes, the merchants were resettled to Haithabu. Dierkow prospered from the late 8th to the early 9th century.

Scandinavian settlements on the Pomeranian coast include Wolin (on the isle of Wolin), Ralswiek (on the isle of Rügen), Altes Lager Menzlin (on the lower Peene river), and Bardy-Świelubie near modern Kołobrzeg. Menzlin was set up in the mid-8th century. Wolin and Ralswiek began to prosper in the course of the 9th century. A merchants' settlement has also been suggested near Arkona, but no archeological evidence supports this theory. Menzlin and Bardy-Świelubie were vacated in the late 9th century, Ralswiek made it into the new millennium, but, by the time written chronicles reported the site in the 12th century, it had lost all its importance. Wolin, thought to be identical with the legendary Vineta and the semilegendary Jomsborg, base of the Jomsvikings, was destroyed by the Danes in the 12th century.

Scandinavian arrowheads from the 8th and 9th centuries were found between the coast and the lake chains in the Mecklenburgian and Pomeranian hinterlands, pointing at periods of warfare between the Scandinavians and Slavs.

Scandinavian settlements existed along the southeastern Baltic coast in Truso and Kaup (Old Prussia), and in Grobin (Courland, Latvia).

Western and Southern Europe

Frisia

In the historical context, Frisia was a region which spanned from around modern-day Bruges to the islands on the west coast of Jutland.

This region was progressively brought under Frankish control (Frisian-Frankish Wars but the Christianisation of the local population and cultural assimilation was a slow process. There is evidence that Frisians sometimes became Vikings themselves

At the same time, several Frisian towns, most notably Dorestad were raided by Vikings.

On Wieringen the Vikings most likely had a base of operations.

Some Viking leaders took an active role in Frisian politics, like Godfrid, Duke of Frisia.

France

The French region of Normandy takes its name from the Viking invaders who were called Normanni, which means ‘men of the North'.

The first Viking raids began between 790 and 800 along the coasts of western France. They were carried out primarily in the summer, as the Vikings wintered in Scandinavia. Several coastal areas were lost to Francia during the reign of Louis the Pious (814–840). But the Vikings took advantage of the quarrels in the royal family caused after the death of Louis the Pious to settle their first colony in the south-west (Gascony) of the kingdom of Francia, which was more or less abandoned by the Frankish kings after their two defeats at Roncevaux. The incursions in 841 caused severe damage to Rouen and Jumièges. The Viking attackers sought to capture the treasures stored at monasteries, easy prey given the monks' lack of defensive capacity. In 845 an expedition up the Seine reached Paris. The presence of Carolingian deniers of ca 847, found in 1871 among a hoard at Mullaghboden, County Limerick, where coins were neither minted nor normally used in trade, probably represents booty from the raids of 843–846.

However, from 885 to 886, Odo of Paris (Eudes de Paris) succeeded in defending Paris against Viking raiders. His military success allowed him to replace the Carolingians. In 911, a band of Viking warriors attempted to siege Chartres but was defeated by Robert I of France. Robert's victory later paved way for the baptism, and settlement in Normandy, of Viking leader Rollo. Rollo reached an agreement with Charles the Simple to sign the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, under which Charles gave Rouen and the area of present-day Upper Normandy to Rollo, establishing the Duchy of Normandy. In exchange, Rollo pledged vassalage to Charles in 940, agreed to be baptised, and vowed to guard the estuaries of the Seine from further Viking attacks. During Rollo's baptism Robert I of France stood as his godfather. The Duchy of Normandy also annexed further areas in Northern France, expanding the territory which was originally negotiated.

The Scandinavian expansion included Danish and Norwegian as well as Swedish elements, all under the leadership of Rollo. By the end of the reign of Richard I of Normandy in 996 (aka Richard the Fearless / Richard sans Peur), all descendants of Vikings became, according to Cambridge Medieval History (Volume 5, Chapter XV), 'not only Christians but in all essentials Frenchmen'. During the Middle Ages, the Normans created one of the most powerful feudal states of Western Europe. The Normans conquered England and southern Italy in 11th century, and played a key role in the Crusades.

Italy

In 860, according to an account by the Norman monk Dudo of Saint-Quentin, a Viking fleet, probably under Björn Ironside and Hastein, landed at the Ligurian port of Luni and sacked the city. The Vikings then moved another 60 miles down the Tuscan coast to the mouth of the Arno, sacking Pisa and then, following the river upstream, also the hill-town of Fiesole above Florence, among other victories around the Mediterranean (including in Sicily and North Africa).

Many Anglo-Danish and Varangian mercenaries fought in Southern Italy, including Harald Hardrada and William de Hauteville who conquered parts of Sicily between 1038 and 1040, and Edgar the Ætheling who fought in the Norman conquest of southern Italy. Runestones were raised in Sweden in memory of warriors who died in Langbarðaland (Land of the Lombards), the Old Norse name for southern Italy.

Several Anglo-Danish and Norwegian nobles participated in the Norman conquest of southern Italy, like Edgar the Ætheling, who left England in 1086, and Jarl Erling Skakke, who won his nickname ("Skakke", meaning bent head) after a battle against Arabs in Sicily. On the other hand, many Anglo-Danish rebels fleeing William the Conqueror, joined the Byzantines in their struggle against the Robert Guiscard, duke of Apulia, in Southern Italy.

Spain

After 842, when the Vikings set up a permanent base at the mouth of the Loire river, they could strike as far as northern Spain. They attacked Cádiz in 844. In some of their raids, they were crushed either by Asturian or Cordoban armies. These Vikings were Hispanicized in all Christian kingdoms, while they kept their ethnic identity and culture in Al-Andalus.

In 1015, a Viking fleet entered the river Minho and sacked the episcopal city of Tui (Galicia); no new bishop was appointed until 1070.

Portugal

In 844, many dozens of drakkars appeared in the "Mar da Palha" ("the Sea of Straw", mouth of the Tagus river). After a siege, the Vikings conquered Lisbon (at the time, the city was under Muslim rule and known as Lashbuna). They left after 13 days, following a resistance led by Alah Ibn Hazm and the city's inhabitants. Another raid was attempted in 966, without success.

North America

Greenland

The Viking-Age settlements in Greenland were established in the sheltered fjords of the southern and western coast. They settled in three separate areas along roughly 650 km (350 nmi; 400 mi) of the western coast. While harsh, the microclimates along some fjords allowed for a pastoral lifestyle similar to that of Iceland, until the climate changed for the worse with the Little Ice Age around 1400.

- The Eastern Settlement: The remains of about 450 farms have been found here. Erik the Red settled at Brattahlid on Ericsfjord.

- The Middle Settlement, near modern Ivigtut, consisted of about 20 farms.

- The Western Settlement at modern Godthåbsfjord, was established before the 12th century. It has been extensively excavated by archaeologists.

Mainland North America

In about 986, the Norwegian Vikings Bjarni Herjólfsson, Leif Ericson and Þórfinnr Karlsefni from Greenland reached Mainland North America, over 500 years before Christopher Columbus, and they attempted to settle the land they called Vinland. They created a small settlement on the northern peninsula of present-day Newfoundland, near L'Anse aux Meadows. Conflict with indigenous peoples and lack of support from Greenland brought the Vinland colony to an end within a few years. The archaeological remains are now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Technology

The Vikings were equipped with the technologically superior longships; for purposes of conducting trade however, another type of ship, the knarr, wider and deeper in draft, were customarily used. The Vikings were competent sailors, adept in land warfare as well as at sea, and they often struck at accessible and poorly defended targets, usually with near impunity. The effectiveness of these tactics earned Vikings a formidable reputation as raiders and pirates.

The Vikings used their longships to travel vast distances and attain certain tactical advantages in battle. They could perform highly efficient hit-and-run attacks, in which they quickly approached a target, then left as rapidly as possible before a counter-offensive could be launched. Because of the ships' negligible draft, the Vikings could sail in shallow waters, allowing them to invade far inland along rivers. The ships were agile, and light enough to be carried over land from one river system to another. "Under sail, the same boats could tackle open water and cross the unexplored wastes of the North Atlantic." The ships' speed was also prodigious for the time, estimated at a maximum of 14–15 knots (26–28 km/h). The use of the longships ended when technology changed, and ships began to be constructed using saws instead of axes, resulting in inferior vessels.

While battles at sea were rare, they would occasionally occur when Viking ships attempted to board European merchant vessels in Scandinavian waters. When larger scale battles ensued, Viking crews would rope together all nearby ships and slowly proceed towards the enemy targets. While advancing, the warriors hurled spears, arrows, and other projectiles at the opponents. When the ships were sufficiently close, melee combat would ensue using axes, swords, and spears until the enemy ship could be easily boarded. The roping technique allowed Viking crews to remain strong in numbers and act as a unit, but this uniformity also created problems. A Viking ship in the line could not retreat or pursue hostiles without breaking the formation and cutting the ropes, which weakened the overall Viking fleet and was a burdensome task to perform in the heat of battle. In general, these tactics enabled Vikings to quickly destroy the meagre opposition posted during raids.

Together with an increasing centralisation of government in the Scandinavian countries, the old system of leidang — a fleet mobilisation system, where every skipreide (ship community) had to maintain one ship and a crew — was discontinued as a purely military institution, as the duty to build and man a ship soon was converted into a tax. The Norwegian leidang was called under Haakon Haakonson for his 1263 expedition to Scotland during the Scottish–Norwegian War, and the last recorded calling of it was in 1603. However, already by the 11th and 12th centuries, European fighting ships were built with raised platforms fore and aft, from which archers could shoot down into the relatively low longships. This led to the defeat of longship navies in most subsequent naval engagements—e.g., with the Hanseatic League.

Exactly how the Vikings navigated the open seas with such success is unclear. While some evidence points to the use of calcite "sunstones" to find the sun's location, modern reproductions of Viking "sky-polarimetric" navigation have found these sun compasses to be highly inaccurate, and not usable in cloudy or foggy weather.

The archaeological find known as the Visby lenses from the Swedish island of Gotland may be components of a telescope. It appears to date from long before the invention of the telescope in the 17th century. Recent evidence suggests that the Vikings also made use of an optical compass as a navigation aid, using the light-splitting and polarisation-filtering properties of Iceland spar to find the location of the sun when it was not directly visible.

Religion

Trade centres

Some of the most important trading ports founded by the Norse during the period include both existing and former cities such as Aarhus (Denmark), Ribe (Denmark), Hedeby (Germany), Vineta (Pomerania), Truso (Poland), Bjørgvin (Norway), Kaupang (Norway), Skiringssal (Norway), Birka (Sweden), Bordeaux (France), York (England), Dublin (Ireland) and Aldeigjuborg (Russia).

One important centre of trade was at Hedeby. Close to the border with the Franks, it was effectively a crossroads between the cultures, until its eventual destruction by the Norwegians in an internecine dispute around 1050. York was the centre of the kingdom of Jórvík from 866, and discoveries there (e.g., a silk cap, a counterfeit of a coin from Samarkand and a cowry shell from the Red Sea or the Persian Gulf) suggest that Scandinavian trade connections in the 10th century reached beyond Byzantium. However, those items could also have been Byzantine imports, and there is no reason to assume that the Varangians travelled significantly beyond Byzantium and the Caspian Sea.

Genetics

A genetic study published at bioRxiv in July 2019 and in Nature in September 2020 examined the population genomics of the Viking Age. 442 ancient humans from across Europe and the North Atlantic were surveyed, stretching from the Bronze Age to the Early Modern Period. In terms of Y-DNA composition, Viking individuals were similar to present-day Scandinavians. The most common Y-DNA haplogroup in the study was I1 (95 samples), R1b (84 samples) and R1a, especially (but not exclusively) of the Scandinavian R1a-Z284 subclade (61 samples). It was found that there was a notable foreign gene flow into Scandinavia in the years preceding the Viking Age and during the Viking Age itself. This gene flow entered Denmark and eastern Sweden, from which it spread into the rest of Scandinavia. The Y-DNA of Viking Age samples suggests that this may partly have been descendants of the Germanic tribes from the Migration Period returning to Scandinavia. The study also found that despite close cultural similarities, there were distinct genetic differences between regional populations in the Viking Age. These differences have persisted into modern times. Inland areas were found to be more genetically homogenous than coastal areas and islands such as Öland and Gotland. These islands were probably important trade settlements. Unsurprisingly, and very much consistent with historical records, the study found evidence of a major influx of Danish Viking ancestry into England, a Swedish influx into Estonia and Finland; and Norwegian influx into Ireland, Iceland and Greenland during the Viking Age. The Vikings were found to have left a profound genetic imprint in the areas they settled, which has persisted into modern times with e.g. the contemporary population of the United Kingdom having up to 6% Viking DNA. The study also showed that some local people of Scotland were buried as Vikings and may have taken on Viking identities.

Margaryan et al. 2020 examined the skeletal remains of 42 individuals from the Salme ship burials in Estonia. The skeletal remains belonged to warriors killed in battle who were later buried together with numerous valuable weapons and armour. DNA testing and isotope analysis revealed that the men came from central Sweden.

Margaryan et al. 2020 examined an elite warrior burial from Bodzia (Poland) dated to 1010-1020 AD. The cemetery in Bodzia is exceptional in terms of Scandinavian and Kievian Rus links. The Bodzia man (sample VK157, or burial E864/I) was not a simple warrior from the princely retinue, but he belonged to the princely family himself. His burial is the richest one in the whole cemetery, moreover, strontium analysis of his teeth enamel shows he was not local. It is assumed that he came to Poland with the Prince of Kiev, Sviatopolk the Accursed, and met a violent death in combat. This corresponds to the events of 1018 AD when Sviatopolk himself disappeared after having retreated from Kiev to Poland. It cannot be excluded that the Bodzia man was Sviatopolk himself, as the genealogy of the Rurikids at this period is extremely sketchy and the dates of birth of many princes of this dynasty may be quite approximative. The Bodzia man carried haplogroup I1-S2077 and had both Scandinavian ancestry and Russian admixture.

The genetic data from these areas affirmed conclusions previously drawn from historical and archaeological evidence.