Major environmental issues caused by contemporary climate change in the Arctic region range from the well-known, such as the loss of sea ice or melting of the Greenland ice sheet, to more obscure, but deeply significant issues, such as permafrost thaw, social consequences for locals and the geopolitical ramifications of these changes. The Arctic is likely to be especially affected by climate change because of the high projected rate of regional warming and associated impacts. Temperature projections for the Arctic region were assessed in 2007: These suggested already averaged warming of about 2 °C to 9 °C by the year 2100. The range reflects different projections made by different climate models, run with different forcing scenarios. Radiative forcing is a measure of the effect of natural and human activities on the climate. Different forcing scenarios reflect, for example, different projections of future human greenhouse gas emissions.

These effects are wide-ranging and can be seen in many Arctic systems, from fauna and flora to territorial claims. Temperatures in the region are rising twice as fast as elsewhere on Earth, leading to these effects worsening year on year and causing significant concern. The changing Arctic has global repercussions, perhaps via ocean circulation changes or arctic amplification.

Impacts on the natural environment

Temperature and weather changes

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, "surface air temperatures (SATs) in the Arctic have warmed at approximately twice the global rate". The period of 1995–2005 was the warmest decade in the Arctic since at least the 17th century, with temperatures 2 °C (3.6 °F) above the 1951–1990 average. In addition, since 2013, Arctic annual mean SAT has been at least 1 °C (1.8 °F) warmer than the 1981-2010 mean. With 2020 having the second warmest SAT anomaly after 2016, being 1.9 °C (3.4 °F) warmer than the 1981-2010 average.

Some regions within the Arctic have warmed even more rapidly, with Alaska and western Canada's temperature rising by 3 to 4 °C (5.40 to 7.20 °F). This warming has been caused not only by the rise in greenhouse gas concentration, but also the deposition of soot on Arctic ice. The smoke from wildfires defined as "brown carbon" also increases arctic warming. Its warming effect is around 30% from the effect of black carbon (soot). As wildfires increses with warming this create a positive feedback loop. A 2013 article published in Geophysical Research Letters has shown that temperatures in the region haven't been as high as they currently are since at least 44,000 years ago and perhaps as long as 120,000 years ago. The authors conclude that "anthropogenic increases in greenhouse gases have led to unprecedented regional warmth."

On 20 June 2020, for the first time, a temperature measurement was made inside the Arctic Circle of 38 °C, more than 100 °F. This kind of weather was expected in the region only by 2100. In March, April and May the average temperature in the Arctic was 10 °C higher than normal. This heat wave, without human - induced warming, could happen only one time in 80,000 years, according to an attribution study published in July 2020. It is the strongest link of a weather event to anthropogenic climate change that had been ever found, for now. Such heat waves are generally a result of an unusual state of the jet stream.

Some scientists suggest that climate change will slow the jet stream by reducing the difference in temperature between the Arctic and more southern territories, because the Arctic is warming faster. This can facilitate the occurring of such heat waves. The scientists do not know if the 2020 heat wave is the result of such change.

A rise of 1.5 degrees in global temperature from the pre-industrial level will probably change the type of precipitation in the Arctic from snow to rain in summer and autumn, which will increase glaciers melting and permafrost thawing. Both effects lead to more warming.

One of the effects of climate change is a strong increase in the number of lightnings in the Arctic. Lightnings increase the risk for wildfires.

Arctic amplification

The poles of the Earth are more sensitive to any change in the planet's climate than the rest of the planet. In the face of ongoing global warming, the poles are warming faster than lower latitudes. The Arctic is warming more than twice as fast as the global average, process known as Arctic amplification (AA). The primary cause of this phenomenon is ice–albedo feedback where, by melting, ice uncovers darker land or ocean beneath, which then absorbs more sunlight, causing more heating. A study from 2019 identified sea-ice loss under increasing CO2 as a main driver for large AA. Thus, large AA only occurs from October to April in areas suffering from important sea-ice loss, because of the "Increased outgoing longwave radiation and heat fluxes from the newly opened waters".

Arctic amplification has been argued to have significant effects on midlatitude weather, contributing to more persistent hot-dry extremes and winter continental cooling.

Black carbon

Black carbon deposits (from the combustion of heavy fuel oil (HFO) of Arctic shipping) absorb solar radiation in the atmosphere and strongly reduce the albedo when deposited on snow and ice, thus accelerating the effect of the melting of snow and sea ice. A 2013 study quantified that gas flaring at petroleum extraction sites contributed over 40% of the black carbon deposited in the Arctic. Recent studies attributed the majority (56%) of Arctic surface black carbon to emissions from Russia, followed by European emissions, and Asia also being a large source.

According to a 2015 study, reductions in black carbon emissions and other minor greenhouse gases, by roughly 60 percent, could cool the Arctic up to 0.2 °C by 2050. However, a 2019 study indicates that "Black carbon emissions will continuously rise due to increased shipping activities", specifically fishing vessels.

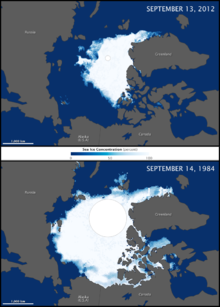

Decline of sea ice

Arctic sea ice decline has occurred in recent decades and is an effect of climate change; sea ice in the Arctic Ocean has melted more than it refreezes in the winter. Global warming, caused by greenhouse gas forcing is responsible for the decline in Arctic sea ice. Implications of arctic sea ice decline may include: Ice-free summer, amplified arctic warming, polar vortex disruption, atmospheric chemistry changes, atmospheric regime changes, changes to plant, animal, and microbial life; changed shipping options and other impacts on humans.

Sea ice in the arctic is currently in decline in area, extent, and volume, and has been accelerating during the early twenty‐first century, with a decline rate of −4.7% per decade (it has declined over 50% since the first satellite records). It is also thought that summertime sea ice will cease to exist sometime during the 21st century. This sea ice loss is one of the main drivers of surface-based Arctic amplification. Sea ice area means the total area covered by ice, whereas sea ice extent is the area of ocean with at least 15% sea ice, while the volume is the total amount of ice in the Arctic.Changes in extent and area

Reliable measurement of sea ice edges began with the satellite era in the late 1970s. Before this time, sea ice area and extent were monitored less precisely by a combination of ships, buoys and aircraft. The data show a long-term negative trend in recent years, attributed to global warming, although there is also a considerable amount of variation from year to year. Some of this variation may be related to effects such as the Arctic oscillation, which may itself be related to global warming.

The rate of the decline in entire Arctic ice coverage is accelerating. From 1979 to 1996, the average per decade decline in entire ice coverage was a 2.2% decline in ice extent and a 3% decline in ice area. For the decade ending 2008, these values have risen to 10.1% and 10.7%, respectively. These are comparable to the September to September loss rates in year-round ice (i.e., perennial ice, which survives throughout the year), which averaged a retreat of 10.2% and 11.4% per decade, respectively, for the period 1979–2007.

The Arctic sea ice September minimum extent (SIE) (i.e., area with at least 15% sea ice coverage) reached new record lows in 2002, 2005, 2007, 2012 (5.32 million km2), 2016 and 2019 (5.65 million km2). The 2007 melt season let to a minimum 39% below the 1979–2000 average, and for the first time in human memory, the fabled Northwest Passage opened completely. During July 2019 the warmest month in the Arctic was recorded, reaching the lowest SIE (7.5 million km2) and sea ice volume (8900 km3). Setting a decadal trend of SIE decline of -13%. As for now, the SIE has shrink by 50% since the 1970s.

From 2008 to 2011, Arctic sea ice minimum extent was higher than 2007, but it did not return to the levels of previous years. In 2012 however, the 2007 record low was broken in late August with three weeks still left in the melt season. It continued to fall, bottoming out on 16 September 2012 at 3.42 million square kilometers (1.32 million square miles), or 760,000 square kilometers (293,000 square miles) below the previous low set on 18 September 2007 and 50% below the 1979–2000 average.

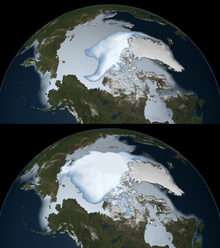

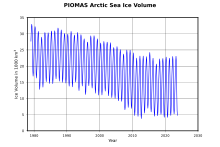

Changes in volume

The sea ice thickness field and accordingly the ice volume and mass, is much more difficult to determine than the extension. Exact measurements can be made only at a limited number of points. Because of large variations in ice and snow thickness and consistency air- and spaceborne-measurements have to be evaluated carefully. Nevertheless, the studies made support the assumption of a dramatic decline in ice age and thickness. While the Arctic ice area and extent show an accelerating downward trend, arctic ice volume shows an even sharper decline than the ice coverage. Since 1979, the ice volume has shrunk by 80% and in just the past decade the volume declined by 36% in the autumn and 9% in the winter. And currently, 70% of the winter sea ice has turned into seasonal ice.

An end to summer sea ice?

The IPCC's Fourth Assessment Report in 2007 summarized the current state of sea ice projections: "the projected reduction [in global sea ice cover] is accelerated in the Arctic, where some models project summer sea ice cover to disappear entirely in the high-emission A2 scenario in the latter part of the 21st century.″ However, current climate models frequently underestimate the rate of sea ice retreat. A summertime ice-free Arctic would be unprecedented in recent geologic history, as currently scientific evidence does not indicate an ice-free polar sea anytime in the last 700,000 years.

The Arctic ocean will likely be free of summer sea ice before the year 2100, but many different dates have been projected, with models showing near-complete to complete loss in September from 2035 to some time around 2067.

Melting of the Greenland ice sheet

Models predict a sea-level contribution of about 5 centimetres (2 in) from melting of the Greenland ice sheet during the 21st century. It is also predicted that Greenland will become warm enough by 2100 to begin an almost complete melt during the next 1,000 years or more. In early July 2012, 97% percent of the ice sheet experienced some form of surface melt, including the summits.

Ice thickness measurements from the GRACE satellite indicate that ice mass loss is accelerating. For the period 2002–2009, the rate of loss increased from 137 Gt/yr to 286 Gt/yr, with every year seeing on average 30 gigatonnes more mass lost than in the preceding year. The rate of melting was 4 times higher in 2019 than in 2003. In the year 2019 the melting contributed 2.2 millimeters to sea level rise in just 2 months. Overall, the signs are overwhelming that melting is not only occurring, but accelerating year on year.

According to a study published in "Nature Communications Earth and Environment" the Greenland ice sheet is possibly past the point of no return, meaning that even if the rise in temperature were to completely stop and even if the climate were to become a little colder, the melting would continue. This outcome is due to the movement of ice from the middle of Greenland to the coast, creating more contact between the ice and warmer coastal water and leading to more melting and calving. Another climate scientist says that after all the ice near the coast melts, the contact between the seawater and the ice will stop what can prevent further warming.

In September 2020, satellite imagery showed that a big chunk of ice shattered into many small pieces from the last remaining ice shelf in Nioghalvfjerdsfjorden, Greenland. This ice sheet is connected to the interior ice sheet, and could prove a hotspot for deglaciation in coming years.

Another unexpected effect of this melting relates to activities by the United States military in the area. Specifically, Camp Century, a nuclear powered base which has been producing nuclear waste over the years. In 2016, a group of scientists evaluated the environmental impact and estimated that due to changing weather patterns over the next few decades, melt water could release the nuclear waste, 20,000 liters of chemical waste and 24 million liters of untreated sewage into the environment. However, so far neither US or Denmark has taken responsibility for the clean-up.

Changes in vegetation

Climate change is expected to have a strong effect on the Arctic's flora, some of which is already being seen. These changes in vegetation are associated with the increases in landscape scale methane emissions, as well as increases in CO2, Tº and the disruption of ecological cycles which affect patterns in nutrient cycling, humidity and other key ecological factors that help shape plant communities.

A large source of information for how vegetation has adapted to climate change over the last years comes from satellite records, which help quantify shifts in vegetation in the Arctic region. For decades, NASA and NOAA satellites have continuously monitored vegetation from space. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) and Advanced Very High-Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) instruments, as well as others, measure the intensity of visible and near-infrared light reflecting off of plant leaves. Scientists use this information to calculate the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), an indicator of photosynthetic activity or “greenness” of the landscape, which is most often used. There also exist other indices, such as the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) or Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI).

These indices can be used as proxies for vegetation productivity, and their shifts over time can provide information on how vegetation changes over time. One of the two most used ways to define shifts in vegetation in the Arctic are the concepts of Arctic greening and Arctic browning. The former refers to a positive trend in the aforementioned greenness indices, indicating increases in plant cover or biomass whereas browning can be broadly understood as a negative trend, with decreases in those variables.

Recent studies have allowed us to get an idea of how these two processes have progressed in recent years. It has been found that from 1985 to 2016, greening has occurred in 37.3% of all sites sampled in the tundra, whereas browning was observed only in 4.7% of them. Certain variables influenced this distribution, as greening was mostly associated with sites with higher summer air temperature, soil temperature and soil moisture. On the other hand, browning was found to be linked with colder sites that were experiencing cooling and drying. Overall, this paints the picture of widespread greening occurring throughout significant portions of the arctic tundra, as a consequence of increases in plant productivity, height, biomass and shrub dominance in the area.

This expansion of vegetation in the Arctic is not equivalent across types of vegetation. One of the most dramatic changes arctic tundras are currently facing is the expansion of shrubs, which, thanks to increases in air temperature and, to a lesser extent, precipitation have contributed to an Arctic-wide trend known as "shrubification", where shrub type plants are taking over areas previously dominated by moss and lichens. This change contributes to the consideration that the tundra biome is currently experiencing the most rapid change of any terrestrial biomes on the planet.

The direct impact on mosses and lichens is unclear as there exist very few studies at species level, but climate change is more likely to cause increased fluctuation and more frequent extreme events. The expansion of shrubs could affect permafrost dynamics, but the picture is quite unclear at the moment. In the winter, shrubs trap more snow, which insulates the permafrost from extreme cold spells, but in the summer they shade the ground from direct sunlight, how these two effects counter and balance each other is not yet well understood. Warming is likely to cause changes in plant communities overall, contributing to the rapid changes tundra ecosystems are facing. While shrubs may increase in range and biomass, warming may also cause a decline in cushion plants such as moss campion, and since cushion plants act as facilitator species across trophic levels and fill important ecological niches in several environments, this could cause cascading effects in these ecosystems that could severely affect the way in which they function and are structured.

The expansion of these shrubs can also have strong effects on other important ecological dynamics, such as the albedo effect. These shrubs change the winter surface of the tundra from undisturbed, uniform snow to mixed surface with protruding branches disrupting the snow cover, this type of snow cover has a lower albedo effect, with reductions of up to 55%, which contributes to a positive feedback loop on regional and global climate warming. This reduction of the albedo effect means that more radiation is absorbed by plants, and thus, surface temperatures increase, which could disrupt current surface-atmosphere energy exchanges and affect thermal regimes of permafrost. Carbon cycling is also being affected by these changes in vegetation, as parts of the tundra increase their shrub cover, they behave more like boreal forests in terms of carbon cycling. This is speeding up the carbon cycle, as warmer temperatures lead to increased permafrost thawing and carbon release, but also carbon capturing from plants that have increased growth. It is not certain whether this balance will go in one direction or the other, but studies have found that it is more likely that this will eventually lead to increased CO2 in the atmosphere.

For a more graphic and geographically focused overview of the situation, maps above show the Arctic Vegetation Index Trend between July 1982 and December 2011 in the Arctic Circle. Shades of green depict areas where plant productivity and abundance increased; shades of brown show where photosynthetic activity declined, both according to the NDVI index. The maps show a ring of greening in the treeless tundra ecosystems of the circumpolar Arctic—the northernmost parts of Canada, Russia, and Scandinavia. Tall shrubs and trees started to grow in areas that were previously dominated by tundra grasses, as part of the previously mentioned "shrubification" of the tundra. Researchers concluded that plant growth had increased by 7% to 10% overall.

However, boreal forests, particularly those in North America, showed a different response to warming. Many boreal forests greened, but the trend was not as strong as it was for tundra of the circumpolar Arctic, mostly characterized by shrub expansion and increased growth. In North America, some boreal forests actually experienced browning over the study period. Droughts, increased forest fire activity, animal behavior, industrial pollution, and a number of other factors may have contributed to browning.

Another important change affecting flora in the arctic is the increase of wildfires in the Arctic Circle, which in 2020 broke its record of CO2 emissions, peaking at 244 megatonnes of carbon dioxide emitted. This is due to the burning of peatlands, carbon-rich soils that originate from the accumulation of waterlogged plants which are mostly found at Arctic latitudes. These peatlands are becoming more likely to burn as temperatures increase, but their own burning and releasing of CO2 contributes to their own likelihood of burning in a positive feedback loop.

In terms of aquatic vegetation, reduction of sea ice has boosted the productivity of phytoplankton by about twenty percent over the past thirty years. However, the effect on marine ecosystems is unclear, since the larger types of phytoplankton, which are the preferred food source of most zooplankton, do not appear to have increased as much as the smaller types. So far, Arctic phytoplankton have not had a significant impact on the global carbon cycle. In summer, the melt ponds on young and thin ice have allowed sunlight to penetrate the ice, in turn allowing phytoplankton to bloom in unexpected concentrations, although it is unknown just how long this phenomenon has been occurring, or what its effect on broader ecological cycles is.

Changes for animals

The northward shift of the subarctic climate zone is allowing animals that are adapted to that climate to move into the far north, where they are replacing species that are more adapted to a pure Arctic climate. Where the Arctic species are not being replaced outright, they are often interbreeding with their southern relations. Among slow-breeding vertebrate species, this usually has the effect of reducing the genetic diversity of the genus. Another concern is the spread of infectious diseases, such as brucellosis or phocine distemper virus, to previously untouched populations. This is a particular danger among marine mammals who were previously segregated by sea ice.

3 April 2007, the National Wildlife Federation urged the United States Congress to place polar bears under the Endangered Species Act. Four months later, the United States Geological Survey completed a year-long study which concluded in part that the floating Arctic sea ice will continue its rapid shrinkage over the next 50 years, consequently wiping out much of the polar bear habitat. The bears would disappear from Alaska, but would continue to exist in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and areas off the northern Greenland coast. Secondary ecological effects are also resultant from the shrinkage of sea ice; for example, polar bears are denied their historic length of seal hunting season due to late formation and early thaw of pack ice.

Similarly, Arctic warming negatively affects the foraging and breeding ecology many other species of arctic marine mammals, such as walruses, seals, foxes or reindeers. In July 2019, 200 Svalbard reindeer were found starved to death apparently due to low precipitation related to climate change.

In the short-term, climate warming may have neutral or positive effects on the nesting cycle of many Arctic-breeding shorebirds.

Permafrost thaw

Permafrost is an important component of hydrological systems and ecosystems within the Arctic landscape. In the Northern Hemisphere the terrestrial permafrost domain comprises around 18 million km2. Within this permafrost region, the total soil organic carbon (SOC) stock is estimated to be 1,460-1,600 Pg (where 1 Pg = 1 billion tons), which constitutes double the amount of carbon currently contained in the atmosphere.

Human caused climate change leads to higher temperatures that cause permafrost thawing in the Arctic. The thawing of the various types of Arctic permafrost could release large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere.

The 2019 Arctic report card estimated that Arctic permafrost releases 0.3 Pg C per year. However, a recent study increased this estimate to 0.6 Pg, since the carbon emitted across the northern permafrost domain during the Arctic winter offsets the average carbon uptake during the growing season in that amount. Under a business-as-usual emissions scenario RCP 8.5, winter CO2 emissions from the norther permafrost domain is predicted to increase 41% by 2100, and 17% under the moderate scenario RCP 4.5.

Abrupt thaw

Permafrost thaw not only occurs gradually when climate warming increases permafrost temperature from the surface and gradually moves down. But abrupt thaw exists in <20% of the permafrost region, affecting half of the permafrost stored carbon. In contrast to gradual permafrost thaw (which extends over decades since warming of the soil surface slowly affects cm by cm), abrupt thaw rapidly affects wide areas of permafrost in a matter of years or even days.Thus, compared to just gradual thaw, abrupt thaw increases carbon emissions by ~125–190%.

Until now Permafrost carbon feedback (PCF) modeling had mainly focussed on gradual permafrost thaw, rather than taking abrupt thaw also into consideration, and therefore greatly underestimating thawing permafrost carbon release. Nevertheless, a study from 2018, by using field observations, radiocarbon dating, and remote sensing to account for thermokarst lakes, determined that abrupt thaw will more than double permafrost carbon emissions by 2100. And a second study from 2020, showed that under a high RCP 8.5 scenario, abrupt thaw carbon emissions across 2.5 million km2 are projected to provide the same feedback as gradual thaw of near-surface permafrost across the whole 18 million km2 it occupies.

Thawing permafrost represents a threat to industrial infrastructure. In May 2020, permafrost melting due to climate change caused the worst oil spill to date in the Arctic. The melting of permafrost caused a collapse of a fuel tank, spilling 6,000 tonnes of diesel into the land, 15,000 into the water. The rivers Ambarnaya, Daldykan and many smaller rivers were polluted. The pollution reached the lake Pyasino that is important to the water supply of the entire Taimyr Peninsula. State of emergency at the federal level was declared. Many buildings and infrastructure are built on permafrost, which cover 65% of Russian territory, and all those can be damaged as it melts. The thawing can also cause leakage of toxic elements from sites of buried toxic waste.

Subsea permafrost

Subsea permafrost occurs beneath the seabed and exists in the continental shelves of the polar regions. Thus, it can be defined as "the unglaciated continental shelf areas exposed during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, ~26 500 BP) that are currently inundated". Large stocks of organic matter (OM) and methane (CH4) are accumulated below and within the subsea permafrost deposits.This source of methane is different from methane clathrates, but contributes to the overall outcome and feedbacks in the Earth's climate system.

Sea ice serves to stabilise methane deposits on and near the shoreline, preventing the clathrate breaking down and venting into the water column and eventually reaching the atmosphere. Methane is released through bubbles from the subsea permafrost into the Ocean (a process called ebullition). During storms, methane levels in the water column drop dramatically, when wind-driven air-sea gas exchange accelerates the ebullition process into the atmosphere. This observed pathway suggests that methane from seabed permafrost will progress rather slowly, instead of abrupt changes. However, Arctic cyclones, fueled by global warming and further accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere could contribute to more release from this methane cache, which is really important for the Arctic. An update to the mechanisms of this permafrost degradation was published in 2017.

The size of today's subsea permafrost has been estimated at around 2 million km2 (~1/5 of the terrestrial permafrost domain size), which constitutes a 30-50% reduction since the LGM. Containing around 560 GtC in OM and 45 GtC in CH4, with a current release of 18 and 38 MtC per year respectively, which is due to the warming and thawing that the subsea permafrost domain has been experiencing since after the LGM (~14000 years ago). In fact, because the subsea permafrost systems responds at millennial timescales to climate warming, the current carbon fluxes it is emitting to the water are in response to climatic changes occurring after the LGM. Therefore, human-driven climate change effects on subsea permafrost will only be seen hundreds or thousands of years from today. According to predictions under a business-as-usual emissions scenario RCP 8.5, by 2100, 43 GtC could be released from the subsea permafrost domain, and 190 GtC by the year 2300. Whereas for the low emissions scenario RCP 2.6, 30% less emissions are estimated. This constitutes a significant anthropogenic-driven acceleration of carbon release in the upcoming centuries.

Effects on other parts of the world

On ocean circulation

Although this is now thought unlikely in the near future, it has also been suggested that there could be a shutdown of thermohaline circulation, similar to that which is believed to have driven the Younger Dryas, an abrupt climate change event. Even if a full shutdown is unlikely, a slowing down of this current and a weakening of its effects on climate has already been seen, with a 2015 study finding that the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) has weakened by 15% to 20% over the last 100 years. This slowing could lead to cooling in the North Atlantic, although this could be mitigated by global warming, but it is not clear up to what extent. Additional effects of this would be felt around the globe, with changes in tropical patterns, stronger storms in the North Atlantic and reduced European crop productivity among the potential repercussions.

There is also potentially a possibility of a more general disruption of ocean circulation, which may lead to an ocean anoxic event; these are believed to be much more common in the distant past. It is unclear whether the appropriate pre-conditions for such an event exist today, but these ocean anoxic events are thought to have been mainly caused by nutrient run-off, which was driven by increased CO2 emissions in the distant past. This draws an unsettling parallel with current climate change, but the amount of CO2 that's thought to have caused these events is far higher than the levels we're currently facing, so effects of this magnitude are considered unlikely on a short time scale.

On extremely cold winter weather

In 2021, scientists reported that the accelerated, higher-variability warming of the Arctic is causing more frequent extremely cold winter weather across parts of Asia and North America – including the February 2021 North American cold wave – via a, observed and modeled, stratospheric polar vortex disruption. However, before the study, some researchers stated that warming will make such events less likely. Such conclusions are considered to still be highly controversial.

Impacts on people

Territorial claims

Growing evidence that global warming is shrinking polar ice has added to the urgency of several nations' Arctic territorial claims in hopes of establishing resource development and new shipping lanes, in addition to protecting sovereign rights.

As ice sea coverage decreases more and more, year on year, Arctic countries (Russia, Canada, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, the United States and Denmark representing Greenland) are making moves on the geopolitical stage to ensure access to potential new shipping lanes, oil and gas reserves, leading to overlapping claims across the region. However, there is only one single land border dispute in the Arctic, with all others relating to the sea, that is Hans Island. This small uninhabited island lies in the Nares strait, between Canada's Ellesmere Island and the northern coast of Greenland. Its status comes from its geographical position, right between the equidistant boundaries determined in a 1973 treaty between Canada and Denmark. Even though both countries have acknowledged the possibility of splitting the island, no agreement on the island has been reached, with both nations still claiming it for themselves.

There is more activity in terms of maritime boundaries between countries, where overlapping claims for internal waters, territorial seas and particularly Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) can cause frictions between nations. Currently, official maritime borders have an unclaimed triangle of international waters lying between them, that is at the centerpoint of international disputes.

This unclaimed land can be obtainable by submitting a claim to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, these claims can be based on geological evidence that continental shelves extend beyond their current maritime borders and into international waters.

Some overlapping claims are still pending resolution by international bodies, such as a large portion containing the north pole that is both claimed by Denmark and Russia, with some parts of it also contested by Canada. Another example is that of the Northwest Passage, globally recognized as international waters, but technically in Canadian waters. This has led to Canada wanting to limit the number of ships that can go through for environmental reasons but the United States disputes that they have the authority to do so, favouring unlimited passage of vessels.

Impacts on indigenous peoples

As climate change speeds up, it is having more and more of a direct impact on societies around the world. This is particularly true of people that live in the Arctic, where increases in temperature are occurring at faster rates than at other latitudes in the world, and where traditional ways of living, deeply connected with the natural arctic environment are at particular risk of environmental disruption caused by these changes.

The warming of the atmosphere and ecological changes that come alongside it presents challenges to local communities such as the Inuit. Hunting, which is a major way of survival for some small communities, will be changed with increasing temperatures. The reduction of sea ice will cause certain species populations to decline or even become extinct. Inuit communities are deeply reliant on seal hunting, which is dependent on sea ice flats, where seals are hunted.

Unsuspected changes in river and snow conditions will cause herds of animals, including reindeer, to change migration patterns, calving grounds, and forage availability. In good years, some communities are fully employed by the commercial harvest of certain animals. The harvest of different animals fluctuates each year and with the rise of temperatures it is likely to continue changing and creating issues for Inuit hunters, as unpredictability and disruption of ecological cycles further complicate life in these communities, which already face significant problems, such as Inuit communities being the poorest and most unemployed of North America.

Other forms of transportation in the Arctic have seen negative impacts from the current warming, with some transportation routes and pipelines on land being disrupted by the melting of ice. Many Arctic communities rely on frozen roadways to transport supplies and travel from area to area. The changing landscape and unpredictability of weather is creating new challenges in the Arctic. Researchers have documented historical and current trails created by the Inuit in the Pan Inuit Trails Atlas, finding that the change in sea ice formation and breakup has resulted in changes to the routes of trails created by the Inuit.

The Transpolar Sea Route is a future Arctic shipping lane running from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean across the center of the Arctic Ocean. The route is also sometimes called Trans-Arctic Route. In contrast to the Northeast Passage (including the Northern Sea Route) and the North-West Passage it largely avoids the territorial waters of Arctic states and lies in international high seas.

Governments and private industry have shown a growing interest in the Arctic. Major new shipping lanes are opening up: the northern sea route had 34 passages in 2011 while the Northwest Passage had 22 traverses, more than any time in history. Shipping companies may benefit from the shortened distance of these northern routes. Access to natural resources will increase, including valuable minerals and offshore oil and gas. Finding and controlling these resources will be difficult with the continually moving ice. Tourism may also increase as less sea ice will improve safety and accessibility to the Arctic.

The melting of Arctic ice caps is likely to increase traffic in and the commercial viability of the Northern Sea Route. One study, for instance, projects, "remarkable shifts in trade flows between Asia and Europe, diversion of trade within Europe, heavy shipping traffic in the Arctic and a substantial drop in Suez traffic. Projected shifts in trade also imply substantial pressure on an already threatened Arctic ecosystem."

Adaptation

Research

National

Individual countries within the Arctic zone, Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States (Alaska) conduct independent research through a variety of organizations and agencies, public and private, such as Russia's Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute. Countries who do not have Arctic claims, but are close neighbors, conduct Arctic research as well, such as the Chinese Arctic and Antarctic Administration (CAA). The United States's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) produces an Arctic Report Card annually, containing peer-reviewed information on recent observations of environmental conditions in the Arctic relative to historical records.

International

International cooperative research between nations has become increasingly important:

- Arctic climate change is summarized by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its series of Assessment Reports and the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment.

- European Space Agency (ESA) launched CryoSat-2 on 8 April 2010. It provides satellite data on Arctic ice cover change rates.

- International Arctic Buoy Program: deploys and maintains buoys that provide real-time position, pressure, temperature, and interpolated ice velocity data

- International Arctic Research Center: Main participants are the United States and Japan.

- International Arctic Science Committee: non-governmental organization (NGO) with diverse membership, including 23 countries from 3 continents.

- 'Role of the Arctic Region', in conjunction with the International Polar Year, was the focus of the second international conference on Global Change Research, held in Nynäshamn, Sweden, October 2007.

- SEARCH (Study of Environmental Arctic Change): A research framework originally promoted by several US agencies; an international extension is ISAC (the International Study of Arctic Change).