| Chemical formula for Aluminium sulfate. The formula of aluminium sulfate hexadecahydrate is Al2(SO4)3 · 16H2O. |

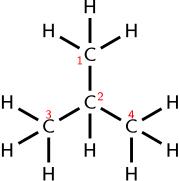

| Structural formula for butane. Examples of other chemical formulae for butane are the empirical formula C2H5, the molecular formula C4H10 and the condensed (or semi-structural) formula CH3CH2CH2CH3. |

In chemistry, a chemical formula is a way of presenting information about the chemical proportions of atoms that constitute a particular chemical compound or molecule, using chemical element symbols, numbers, and sometimes also other symbols, such as parentheses, dashes, brackets, commas and plus (+) and minus (−) signs. These are limited to a single typographic line of symbols, which may include subscripts and superscripts. A chemical formula is not a chemical name, and it contains no words. Although a chemical formula may imply certain simple chemical structures, it is not the same as a full chemical structural formula. Chemical formulae can fully specify the structure of only the simplest of molecules and chemical substances, and are generally more limited in power than chemical names and structural formulae.

The simplest types of chemical formulae are called empirical formulae, which use letters and numbers indicating the numerical proportions of atoms of each type. Molecular formulae indicate the simple numbers of each type of atom in a molecule, with no information on structure. For example, the empirical formula for glucose is CH2O (twice as many hydrogen atoms as carbon and oxygen), while its molecular formula is C6H12O6 (12 hydrogen atoms, six carbon and oxygen atoms).

Sometimes a chemical formula is complicated by being written as a condensed formula (or condensed molecular formula, occasionally called a "semi-structural formula"), which conveys additional information about the particular ways in which the atoms are chemically bonded together, either in covalent bonds, ionic bonds, or various combinations of these types. This is possible if the relevant bonding is easy to show in one dimension. An example is the condensed molecular/chemical formula for ethanol, which is CH3−CH2−OH or CH3CH2OH. However, even a condensed chemical formula is necessarily limited in its ability to show complex bonding relationships between atoms, especially atoms that have bonds to four or more different substituents.

Since a chemical formula must be expressed as a single line of chemical element symbols, it often cannot be as informative as a true structural formula, which is a graphical representation of the spatial relationship between atoms in chemical compounds (see for example the figure for butane structural and chemical formulae, at right). For reasons of structural complexity, a single condensed chemical formula (or semi-structural formula) may correspond to different molecules, known as isomers. For example, glucose shares its molecular formula C6H12O6 with a number of other sugars, including fructose, galactose and mannose. Linear equivalent chemical names exist that can and do specify uniquely any complex structural formula (see chemical nomenclature), but such names must use many terms (words), rather than the simple element symbols, numbers, and simple typographical symbols that define a chemical formula.

Chemical formulae may be used in chemical equations to describe chemical reactions and other chemical transformations, such as the dissolving of ionic compounds into solution. While, as noted, chemical formulae do not have the full power of structural formulae to show chemical relationships between atoms, they are sufficient to keep track of numbers of atoms and numbers of electrical charges in chemical reactions, thus balancing chemical equations so that these equations can be used in chemical problems involving conservation of atoms, and conservation of electric charge.

Overview

A chemical formula identifies each constituent element by its chemical symbol and indicates the proportionate number of atoms of each element. In empirical formulae, these proportions begin with a key element and then assign numbers of atoms of the other elements in the compound, by ratios to the key element. For molecular compounds, these ratio numbers can all be expressed as whole numbers. For example, the empirical formula of ethanol may be written C2H6O because the molecules of ethanol all contain two carbon atoms, six hydrogen atoms, and one oxygen atom. Some types of ionic compounds, however, cannot be written with entirely whole-number empirical formulae. An example is boron carbide, whose formula of CBn is a variable non-whole number ratio with n ranging from over 4 to more than 6.5.

When the chemical compound of the formula consists of simple molecules, chemical formulae often employ ways to suggest the structure of the molecule. These types of formulae are variously known as molecular formulae and condensed formulae. A molecular formula enumerates the number of atoms to reflect those in the molecule, so that the molecular formula for glucose is C6H12O6 rather than the glucose empirical formula, which is CH2O. However, except for very simple substances, molecular chemical formulae lack needed structural information, and are ambiguous.

For simple molecules, a condensed (or semi-structural) formula is a type of chemical formula that may fully imply a correct structural formula. For example, ethanol may be represented by the condensed chemical formula CH3CH2OH, and dimethyl ether by the condensed formula CH3OCH3. These two molecules have the same empirical and molecular formulae (C2H6O), but may be differentiated by the condensed formulae shown, which are sufficient to represent the full structure of these simple organic compounds.

Condensed chemical formulae may also be used to represent ionic compounds that do not exist as discrete molecules, but nonetheless do contain covalently bound clusters within them. These polyatomic ions are groups of atoms that are covalently bound together and have an overall ionic charge, such as the sulfate [SO4]2- ion. Each polyatomic ion in a compound is written individually in order to illustrate the separate groupings. For example, the compound dichlorine hexoxide has an empirical formula ClO3, and molecular formula Cl2O6, but in liquid or solid forms, this compound is more correctly shown by an ionic condensed formula [ClO2]+[ClO4]−, which illustrates that this compound consists of [ClO2]+ ions and [ClO4]− ions. In such cases, the condensed formula only need be complex enough to show at least one of each ionic species.

Chemical formulae as described here are distinct from the far more complex chemical systematic names that are used in various systems of chemical nomenclature. For example, one systematic name for glucose is (2R,3S,4R,5R)-2,3,4,5,6-pentahydroxyhexanal. This name, interpreted by the rules behind it, fully specifies glucose's structural formula, but the name is not a chemical formula as usually understood, and uses terms and words not used in chemical formulae. Such names, unlike basic formulae, may be able to represent full structural formulae without graphs.

Types

Empirical formula

In chemistry, the empirical formula of a chemical is a simple expression of the relative number of each type of atom or ratio of the elements in the compound. Empirical formulae are the standard for ionic compounds, such as CaCl2, and for macromolecules, such as SiO2. An empirical formula makes no reference to isomerism, structure, or absolute number of atoms. The term empirical refers to the process of elemental analysis, a technique of analytical chemistry used to determine the relative percent composition of a pure chemical substance by element.

For example, hexane has a molecular formula of C6H14, and (for one of its isomers, n-hexane) a structural formula CH3CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3, implying that it has a chain structure of 6 carbon atoms, and 14 hydrogen atoms. However, the empirical formula for hexane is C3H7. Likewise the empirical formula for hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, is simply HO, expressing the 1:1 ratio of component elements. Formaldehyde and acetic acid have the same empirical formula, CH2O. This is the actual chemical formula for formaldehyde, but acetic acid has double the number of atoms.

Molecular formula

Molecular formulae indicate the simple numbers of each type of atom in a molecule of a molecular substance. They are the same as empirical formulae for molecules that only have one atom of a particular type, but otherwise may have larger numbers. An example of the difference is the empirical formula for glucose, which is CH2O (ratio 1:2:1), while its molecular formula is C6H12O6 (number of atoms 6:12:6). For water, both formulae are H2O. A molecular formula provides more information about a molecule than its empirical formula, but is more difficult to establish.

A molecular formula shows the number of elements in a molecule, and determines whether it is a binary compound, ternary compound, quaternary compound, or has even more elements.

Structural formula

In addition to quantitative description of a molecule, a structural formula[a] captures how the atoms are organized, and shows (or implies) the chemical bonds between the atoms. There are multiple types of structural formulas focused on different aspects of the molecular structure.

The two diagrams show two molecules which are structural isomers of each other, since they both have the same molecular formula C4H10, but they have different structural formulas as shown.

Condensed formula

The connectivity of a molecule often has a strong influence on its physical and chemical properties and behavior. Two molecules composed of the same numbers of the same types of atoms (i.e. a pair of isomers) might have completely different chemical and/or physical properties if the atoms are connected differently or in different positions. In such cases, a structural formula is useful, as it illustrates which atoms are bonded to which other ones. From the connectivity, it is often possible to deduce the approximate shape of the molecule.

A condensed (or semi-structural) formula may represent the types and spatial arrangement of bonds in a simple chemical substance, though it does not necessarily specify isomers or complex structures. For example, ethane consists of two carbon atoms single-bonded to each other, with each carbon atom having three hydrogen atoms bonded to it. Its chemical formula can be rendered as CH3CH3. In ethylene there is a double bond between the carbon atoms (and thus each carbon only has two hydrogens), therefore the chemical formula may be written: CH2CH2, and the fact that there is a double bond between the carbons is implicit because carbon has a valence of four. However, a more explicit method is to write H2C=CH2 or less commonly H2C::CH2. The two lines (or two pairs of dots) indicate that a double bond connects the atoms on either side of them.

A triple bond may be expressed with three lines (HC≡CH) or three pairs of dots (HC:::CH), and if there may be ambiguity, a single line or pair of dots may be used to indicate a single bond.

Molecules with multiple functional groups that are the same may be expressed by enclosing the repeated group in round brackets. For example, isobutane may be written (CH3)3CH. This condensed structural formula implies a different connectivity from other molecules that can be formed using the same atoms in the same proportions (isomers). The formula (CH3)3CH implies a central carbon atom connected to one hydrogen atom and three methyl groups (CH3). The same number of atoms of each element (10 hydrogens and 4 carbons, or C4H10) may be used to make a straight chain molecule, n-butane: CH3CH2CH2CH3.

Law of composition

In any given chemical compound, the elements always combine in the same proportion with each other. This is the law of constant composition.

The law of constant composition says that, in any particular chemical compound, all samples of that compound will be made up of the same elements in the same proportion or ratio. For example, any water molecule is always made up of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom in a 2:1 ratio. If we look at the relative masses of oxygen and hydrogen in a water molecule, we see that 94% of the mass of a water molecule is accounted for by oxygen and the remaining 6% is the mass of hydrogen. This mass proportion will be the same for any water molecule.[2]

Chemical names in answer to limitations of chemical formulae

The alkene called but-2-ene has two isomers, which the chemical formula CH3CH=CHCH3 does not identify. The relative position of the two methyl groups must be indicated by additional notation denoting whether the methyl groups are on the same side of the double bond (cis or Z) or on the opposite sides from each other (trans or E).

As noted above, in order to represent the full structural formulae of many complex organic and inorganic compounds, chemical nomenclature may be needed which goes well beyond the available resources used above in simple condensed formulae. See IUPAC nomenclature of organic chemistry and IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry 2005 for examples. In addition, linear naming systems such as International Chemical Identifier (InChI) allow a computer to construct a structural formula, and simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) allows a more human-readable ASCII input. However, all these nomenclature systems go beyond the standards of chemical formulae, and technically are chemical naming systems, not formula systems.

Polymers in condensed formulae

For polymers in condensed chemical formulae, parentheses are placed around the repeating unit. For example, a hydrocarbon molecule that is described as CH3(CH2)50CH3, is a molecule with fifty repeating units. If the number of repeating units is unknown or variable, the letter n may be used to indicate this formula: CH3(CH2)nCH3.

Ions in condensed formulae

For ions, the charge on a particular atom may be denoted with a right-hand superscript. For example, Na+, or Cu2+. The total charge on a charged molecule or a polyatomic ion may also be shown in this way, such as for hydronium, H3O+, or sulfate, SO2−4. Note that + and - are used in place of +1 and -1, respectively.

For more complex ions, brackets [ ] are often used to enclose the ionic formula, as in [B12H12]2−, which is found in compounds such as caesium dodecaborate, Cs2[B12H12]. Parentheses ( ) can be nested inside brackets to indicate a repeating unit, as in Hexamminecobalt(III) chloride, [Co(NH3)6]3+Cl−3. Here, (NH3)6 indicates that the ion contains six ammine groups (NH3) bonded to cobalt, and [ ] encloses the entire formula of the ion with charge +3.

This is strictly optional; a chemical formula is valid with or without ionization information, and Hexamminecobalt(III) chloride may be written as [Co(NH3)6]3+Cl−3 or [Co(NH3)6]Cl3. Brackets, like parentheses, behave in chemistry as they do in mathematics, grouping terms together – they are not specifically employed only for ionization states. In the latter case here, the parentheses indicate 6 groups all of the same shape, bonded to another group of size 1 (the cobalt atom), and then the entire bundle, as a group, is bonded to 3 chlorine atoms. In the former case, it is clearer that the bond connecting the chlorines is ionic, rather than covalent.

Isotopes

Although isotopes are more relevant to nuclear chemistry or stable isotope chemistry than to conventional chemistry, different isotopes may be indicated with a prefixed superscript in a chemical formula. For example, the phosphate ion containing radioactive phosphorus-32 is [32PO4]3-. Also a study involving stable isotope ratios might include the molecule 18O16O.

A left-hand subscript is sometimes used redundantly to indicate the atomic number. For example, 8O2 for dioxygen, and 16

8O

2 for the most abundant isotopic species of dioxygen. This is convenient when writing equations for nuclear reactions, in order to show the balance of charge more clearly.

Trapped atoms

The "@" notation: M@C60

The @ symbol (at sign) indicates an atom or molecule trapped inside a cage but not chemically bound to it. For example, a buckminsterfullerene (C60) with an atom (M) would simply be represented as MC60 regardless of whether M was inside the fullerene without chemical bonding or outside, bound to one of the carbon atoms. Using the @ symbol, this would be denoted M@C60 if M was inside the carbon network. A non-fullerene example is [As@Ni12As20]3−, an ion in which one arsenic (As) atom is trapped in a cage formed by the other 32 atoms.

This notation was proposed in 1991 with the discovery of fullerene cages (endohedral fullerenes), which can trap atoms such as La to form, for example, La@C60 or La@C82. The choice of the symbol has been explained by the authors as being concise, readily printed and transmitted electronically (the at sign is included in ASCII, which most modern character encoding schemes are based on), and the visual aspects suggesting the structure of an endohedral fullerene.

Non-stoichiometric chemical formulae

Chemical formulae most often use integers for each element. However, there is a class of compounds, called non-stoichiometric compounds, that cannot be represented by small integers. Such a formula might be written using decimal fractions, as in Fe0.95O, or it might include a variable part represented by a letter, as in Fe1-xO, where x is normally much less than 1.

General forms for organic compounds

A chemical formula used for a series of compounds that differ from each other by a constant unit is called a general formula. It generates a homologous series of chemical formulae. For example, alcohols may be represented by the formula CnH2n + 1OH (n ≥ 1), giving the homologs methanol, ethanol, propanol for 1 ≤ n ≤ 3.

Hill system

The Hill system (or Hill notation) is a system of writing empirical chemical formulae, molecular chemical formulae and components of a condensed formula such that the number of carbon atoms in a molecule is indicated first, the number of hydrogen atoms next, and then the number of all other chemical elements subsequently, in alphabetical order of the chemical symbols. When the formula contains no carbon, all the elements, including hydrogen, are listed alphabetically.

By sorting formulae according to the number of atoms of each element present in the formula according to these rules, with differences in earlier elements or numbers being treated as more significant than differences in any later element or number—like sorting text strings into lexicographical order—it is possible to collate chemical formulae into what is known as Hill system order.

The Hill system was first published by Edwin A. Hill of the United States Patent and Trademark Office in 1900. It is the most commonly used system in chemical databases and printed indexes to sort lists of compounds.

A list of formulae in Hill system order is arranged alphabetically, as above, with single-letter elements coming before two-letter symbols when the symbols begin with the same letter (so "B" comes before "Be", which comes before "Br").

The following example formulae are written using the Hill system, and listed in Hill order:

- BrI

- BrClH2Si

- CCl4

- CH3I

- C2H5Br

- H2O4S