| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophy_of_religion |

Philosophy of religion is "the philosophical examination of the central themes and concepts involved in religious traditions". Philosophical discussions on such topics date from ancient times, and appear in the earliest known texts concerning philosophy. The field is related to many other branches of philosophy, including metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics.

The philosophy of religion differs from religious philosophy in that it seeks to discuss questions regarding the nature of religion as a whole, rather than examining the problems brought forth by a particular belief-system. It can be carried out dispassionately by those who identify as believers or non-believers.

Overview

Philosopher William L. Rowe characterized the philosophy of religion as: "the critical examination of basic religious beliefs and concepts." Philosophy of religion covers alternative beliefs about God or gods or both, the varieties of religious experience, the interplay between science and religion, the nature and scope of good and evil, and religious treatments of birth, history, and death. The field also includes the ethical implications of religious commitments, the relation between faith, reason, experience and tradition, concepts of the miraculous, the sacred revelation, mysticism, power, and salvation.

The term philosophy of religion did not come into general use in the West until the nineteenth century, and most pre-modern and early modern philosophical works included a mixture of religious themes and non-religious philosophical questions. In Asia, examples include texts such as the Hindu Upanishads, the works of Daoism and Confucianism and Buddhist texts. Greek philosophies like Pythagoreanism and Stoicism included religious elements and theories about deities, and Medieval philosophy was strongly influenced by the big three monotheistic Abrahamic religions. In the Western world, early modern philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and George Berkeley discussed religious topics alongside secular philosophical issues as well.

The philosophy of religion has been distinguished from theology by pointing out that, for theology, "its critical reflections are based on religious convictions". Also, "theology is responsible to an authority that initiates its thinking, speaking, and witnessing ... [while] philosophy bases its arguments on the ground of timeless evidence."

Some aspects of philosophy of religion have classically been regarded as a part of metaphysics. In Aristotle's Metaphysics, the necessarily prior cause of eternal motion was an unmoved mover, who, like the object of desire, or of thought, inspires motion without itself being moved. Today, however, philosophers have adopted the term "philosophy of religion" for the subject, and typically it is regarded as a separate field of specialization, although it is also still treated by some, particularly Catholic philosophers, as a part of metaphysics.

Basic themes and problems

Ultimate reality

Different religions have different ideas about ultimate reality, its source or ground (or lack thereof) and also about what is the "Maximal Greatness". Paul Tillich's concept of 'Ultimate Concern' and Rudolf Otto's 'Idea of the Holy' are concepts which point to concerns about the ultimate or highest truth which most religious philosophies deal with in some way. One of the main differences among religions is whether the ultimate reality is a personal god or an impersonal reality.

In Western religions, various forms of theism are the most common conceptions, while in Eastern religions, there are theistic and also various non-theistic conceptions of the Ultimate. Theistic vs non-theistic is a common way of sorting the different types of religions.

There are also several philosophical positions with regard to the existence of God that one might take including various forms of theism (such as monotheism and polytheism), agnosticism and different forms of atheism.

Monotheism

Keith Yandell outlines roughly three kinds of historical monotheisms: Greek, Semitic and Hindu. Greek monotheism holds that the world has always existed and does not believe in creationism or divine providence, while Semitic monotheism believes the world was created by a God at a particular point in time and that this God acts in the world. Indian monotheism teaches that the world is beginningless, but that there is God's act of creation which sustains the world.

The attempt to provide proofs or arguments for the existence of God is one aspect of what is known as natural theology or the natural theistic project. This strand of natural theology attempts to justify belief in God by independent grounds. Perhaps most of the philosophy of religion is predicated on natural theology's assumption that the existence of God can be justified or warranted on rational grounds. There has been considerable philosophical and theological debate about the kinds of proofs, justifications and arguments that are appropriate for this discourse.

Non-theistic conceptions

Eastern religions have included both theistic and other alternative positions about the ultimate nature of reality. One such view is Jainism, which holds a dualistic view that all that exists is matter and a multiplicity of souls (jiva), without depending on a supreme deity for their existence. There are also different Buddhist views, such as the Theravada Abhidharma view, which holds that the only ultimately existing things are transitory phenomenal events (dharmas) and their interdependent relations. Madhyamaka Buddhists such as Nagarjuna hold that ultimate reality is emptiness (shunyata) while the Yogacara holds that it is vijñapti (mental phenomena). In Indian philosophical discourses, monotheism was defended by Hindu philosophers (particularly the Nyaya school), while Buddhist thinkers argued against their conception of a creator god (Sanskrit: Ishvara).

The Hindu view of Advaita Vedanta, as defended by Adi Shankara, is a total non-dualism. Although Advaitins do believe in the usual Hindu gods, their view of ultimate reality is a radically monistic oneness (Brahman without qualities) and anything which appears (like persons and gods) is illusory (maya).

The various philosophical positions of Taoism can also be viewed as non-theistic about the ultimate reality (Tao). Taoist philosophers have conceived of different ways of describing the ultimate nature of things. For example, while the Taoist Xuanxue thinker Wang Bi argued that everything is "rooted" in Wu (non-being, nothingness), Guo Xiang rejected Wu as the ultimate source of things, instead arguing that the ultimate nature of the Tao is "spontaneous self-production" (zi sheng) and "spontaneous self-transformation" (zi hua).

Traditionally, Jains and Buddhists did not rule out the existence of limited deities or divine beings, they only rejected the idea of a single all-powerful creator God or First cause posited by monotheists.

Knowledge and belief

All religious traditions make knowledge claims which they argue are central to religious practice and to the ultimate solution to the main problem of human life. These include epistemic, metaphysical and ethical claims.

Evidentialism is the position that may be characterized as "a belief is rationally justified only if there is sufficient evidence for it". Many theists and non-theists are evidentialists, for example, Aquinas and Bertrand Russell agree that belief in God is rational only if there is sufficient evidence, but disagree on whether such evidence exists. These arguments often stipulate that subjective religious experiences are not reasonable evidence and thus religious truths must be argued based on non-religious evidence. One of the strongest positions of evidentialism is that by William Kingdon Clifford who wrote: "It is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence". His view of evidentialism is usually read in tandem with William James's article A Will to Believe (1896), which argues against Clifford's principle. More recent supporters of evidentialism include Antony Flew ("The Presumption of Atheism", 1972) and Michael Scriven (Primary philosophy, 1966). Both of them rely on the Ockhamist view that in the absence of evidence for X, belief in X is not justified. Many modern Thomists are also evidentialists in that they hold they can demonstrate there is evidence for the belief in God. Another move is to argue in a Bayesian way for the probability of a religious truth like God, not for total conclusive evidence.

Some philosophers, however, argue that religious belief is warranted without evidence and hence are sometimes called non-evidentialists. They include fideists and reformed epistemologists. Alvin Plantinga and other reformed epistemologists are examples of philosophers who argue that religious beliefs are "properly basic beliefs" and that it is not irrational to hold them even though they are not supported by any evidence. The rationale here is that some beliefs we hold must be foundational and not be based on further rational beliefs. If this is not so we risk an infinite regress. This is qualified by the proviso that they can be defended against objections (this differentiates this view from fideism). A properly basic belief is a belief that one can reasonably hold without evidence, such as a memory, a basic sensation or a perception. Plantinga's argument is that belief in God is of this type because within every human mind there is a natural awareness of divinity.

William James in his essay "The Will to Believe" argues for a pragmatic conception of religious belief. For James, religious belief is justified if one is presented with a question which is rationally undecidable and if one is presented with genuine and live options which are relevant for the individual. For James, religious belief is defensible because of the pragmatic value it can bring to one's life, even if there is no rational evidence for it.

Some work in recent epistemology of religion goes beyond debates over evidentialism, fideism, and reformed epistemology to consider contemporary issues deriving from new ideas about knowledge-how and practical skill; how practical factors can affect whether one could know whether theism is true; from formal epistemology's use of probability theory; or from social epistemology (particularly the epistemology of testimony, or the epistemology of disagreement).

For example, an important topic in the epistemology of religion is that of religious disagreement, and the issue of what it means for intelligent individuals of the same epistemic parity to disagree about religious issues. Religious disagreement has been seen as possibly posing first-order or higher-order problems for religious belief. A first order problem refers to whether that evidence directly applies to the truth of any religious proposition, while a higher order problem instead applies to whether one has rationally assessed the first order evidence. One example of a first order problem is the Argument from nonbelief. Higher order discussions focus on whether religious disagreement with epistemic peers (someone whose epistemic ability is equal to our own) demands us to adopt a skeptical or agnostic stance or whether to reduce or change our religious beliefs.

Faith and reason

While religions resort to rational arguments to attempt to establish their views, they also claim that religious belief is at least partially to be accepted through faith, confidence or trust in one's religious belief. There are different conceptions or models of faith, including:

- The affective model of faith sees it as a feeling of trust, a psychological state

- The special knowledge model of faith as revealing specific religious truths (defended by Reformed epistemology)

- The belief model of faith as the theoretical conviction that a certain religious claim is true.

- Faith as trusting, as making a fiducial commitment such as trusting in God.

- The practical doxastic venture model where faith is seen as a commitment to believe in the trustworthiness of a religious truth or in God. In other words, to trust in God presupposes belief, thus faith must include elements of belief and trust.

- The non-doxastic venture model of faith as practical commitment without actual belief (defended by figures such as Robert Audi, J. L. Schellenberg and Don Cupitt). In this view, one need not believe in literal religious claims about reality to have religious faith.

- The hope model, faith as hoping

There are also different positions on how faith relates to reason. One example is the belief that faith and reason are compatible and work together, which is the view of Thomas Aquinas and the orthodox view of Catholic natural theology. According to this view, reason establishes certain religious truths and faith (guided by reason) gives us access to truths about the divine which, according to Aquinas, "exceed all the ability of human reason."

Another position on is Fideism, the view that faith is "in some sense independent of, if not outright adversarial toward, reason." Modern philosophers such as Kierkegaard, William James, and Wittgenstein have been associated with this label. Kierkegaard in particular, argued for the necessity of the religious to take a non-rational leap of faith to bridge the gulf between man and God. Wittgensteinian fideism meanwhile sees religious language games as being incommensurate with scientific and metaphysical language games, and that they are autonomous and thus may only be judged on their own standards. The obvious criticism to this is that many religions clearly put forth metaphysical claims.

Several contemporary New Atheist writers which are hostile to religion hold a related view that says that religious claims and scientific claims are opposed to each other and that therefore religions are false.

The Protestant theologian Karl Barth (1886–1968) argued that religious believers have no need to prove their beliefs through reason and thus rejected the project of natural theology. According to Barth, human reason is corrupt and God is utterly different from his creatures, thus we can only rely on God's own revelation for religious knowledge. Barth's view has been termed Neo-orthodoxy. Similarly, D.Z. Phillips argues that God is not intelligible through reason or evidence because God is not an empirical object or a 'being among beings'.

As Brian Davies points out, the problem with positions like Barth's is that they do not help us in deciding between inconsistent and competing revelations of the different religions.

Science

The topic of whether religious beliefs are compatible with science and in what way is also another important topic in the philosophy of religion as well as in theology. This field draws the historical study of their interactions and conflicts, such as the debates in the United States over the teaching of evolution and creationism. There are different models of interaction that have been discussed in the philosophical literature, including:

- Conflict thesis which sees them as being in constant conflict, such as during the reception of the theory of evolution and the current debate over creationism.

- Independence model, both have separate domains, or non-overlapping magisteria

- Dialogue model, some overlap between the fields, they remain separate but share some concepts and presuppositions

- Integration or unification model includes projects like natural theology and process theology

The field also draws the scientific study of religion, particularly by psychologists and sociologists as well as cognitive scientists. Various theories about religion have arisen from these various disciplines. One example is the various evolutionary theories of religion which see the phenomenon as either adaptive or a by-product. Another can be seen in the various theories put forth by the Cognitive science of religion. Some argued that evolutionary or cognitive theories undermine religious belief,

Religious experience

Closely tied to the issues of knowledge and belief is the question of how to interpret religious experiences vis-à-vis their potential for providing knowledge. Religious experiences have been recorded throughout all cultures and are widely diverse. These personal experiences tend to be highly important to individuals who undergo them. Discussions about religious experiences can be said to be informed in part by the question: "what sort of information about what there is might religious experience provide, and how could one tell?"

One could interpret these experiences either veridically, neutrally or as delusions. Both monotheistic and non-monotheistic religious thinkers and mystics have appealed to religious experiences as evidence for their claims about ultimate reality. Philosophers such as Richard Swinburne and William Alston have compared religious experiences to everyday perceptions, that is, both are noetic and have a perceptual object, and thus religious experiences could logically be veridical unless we have a good reason to disbelieve them.

According to Brian Davies common objections against the veridical force of religious experiences include the fact that experience is frequently deceptive and that people who claim an experience of a god may be "mistakenly identifying an object of their experience", or be insane or hallucinating. However, he argues that we cannot deduce from the fact that our experiences are sometimes mistaken, hallucinations or distorted to the conclusion that all religious experiences are mistaken etc. Indeed, a drunken or hallucinating person could still perceive things correctly, therefore these objections cannot be said to necessarily disprove all religious experiences.

According to C. B. Martin, "there are no tests agreed upon to establish genuine experience of God and distinguish it decisively from the ungenuine", and therefore all that religious experiences can establish is the reality of these psychological states.

Naturalistic explanations for religious experiences are often seen as undermining their epistemic value. Explanations such as the fear of death, suggestion, infantile regression, sexual frustration, neurological anomalies ("it's all in the head") as well as the socio-political power that having such experiences might grant to a mystic have been put forward. More recently, some argued that religious experiences are caused by cognitive misattributions. A contrary position was taken by Bertrand Russell who compared the veridical value of religious experiences to the hallucinations of a drunk person: "From a scientific point of view, we can make no distinction between the man who eats little and sees heaven and the man who drinks much and sees snakes. Each is in an abnormal physical condition, and therefore has abnormal perceptions." However, as William L. Rowe notes:

The hidden assumption in Russell's argument is that bodily and mental states that interfere with reliable perceptions of the physical world also interfere with reliable perceptions of a spiritual world beyond the physical, if there is such a spiritual world to be perceived. Perhaps this assumption is reasonable, but it certainly is not obviously true.

In other words, as argued by C.D. Broad, "one might need to be slightly 'cracked'" or at least appear to be mentally and physically abnormal in order to perceive the supranormal spiritual world.

William James meanwhile takes a middle course between accepting mystical experiences as veridical or seeing them as delusional. He argues that for the individual who experiences them, they are authoritative and they break down the authority of the rational mind. Not only that, but according to James, the mystic is justified in this. But when it comes to the non-mystic, the outside observer, they have no reason to regard them as either veridical nor delusive.

The study of religious experiences from the perspective of the field of phenomenology has also been a feature of the philosophy of religion. Key thinkers in this field include William Brede Kristensen and Gerard van der Leeuw.

Types

Just like there are different religions, there are different forms of religious experience. One could have "subject/content" experiences (such as a euphoric meditative state) and "subject/consciousness/object" experiences (such as the perception of having seen a god, i.e. theophany). Experiences of theophany are described in ancient Mediterranean religious works and myths and include the story of Semele who died due to her seeing Zeus and the Biblical story of the Burning bush. Indian texts like the Bhagavad Gita also contain theophanic events. The diversity (sometimes to the point of contradiction) of religious experiences has also been used as an argument against their veridical nature, and as evidence that they are a purely subjective psychological phenomenon.

In Western thought, religious experience (mainly a theistic one) has been described by the likes of Friedrich Schleiermacher, Rudolf Otto and William James. According to Schleiermacher, the distinguishing feature of a religious experience is that "one is overcome by the feeling of absolute dependence." Otto meanwhile, argued that while this was an important element, the most basic feature of religious experiences is that it is numinous. He described this as "non-rational, non-sensory experience or feeling whose primary and immediate object is outside the self" as well as having the qualities of being a mystery, terrifying and fascinating.

Rowe meanwhile defined a religious experience as "an experience in which one senses the immediate presence of the divine." According to Rowe, religious experiences can be divided in the following manner:

- Religious experiences in which one senses the presence of the divine as being distinct from oneself.

- Mystical experiences in which one senses one's own union with a divine presence.

- The extrovertive way looks outward through the senses into the world around us and finds the divine reality there.

- The introvertive way turns inward and finds the divine reality in the deepest part of the self.

Non-monotheistic religions meanwhile also report different experiences from theophany, such as non-dual experiences of oneness and deeply focused meditative states (termed Samadhi in Indian religion) as well as experiences of final enlightenment or liberation (moksha, nirvana, kevala in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism respectively).

Another typology, offered by Chad Meister, differentiates between three major experiences:

- Regenerative experiences, in which an individual feels reborn, transformed or changed radically, usually resulting in religious conversion.

- Charismatic experiences, in which special gifts, abilities, or blessings are manifested (such as healing, visions, etc.)

- Mystical experiences, which can be described using William James qualifications as being: Ineffable, Noetic, transient and passive.

Perennialism vs Constructivism

Another debate on this topic is whether all religious cultures share common core mystical experiences (Perennialism) or whether these experiences are in some way socially and culturally constructed (Constructivism or Contextualism). According to Walter Stace all cultures share mystical experiences of oneness with the external world, as well as introverted "Pure Conscious Events" which is empty of all concepts, thoughts, qualities, etc. except pure consciousness. Similarly Ninian Smart argued that monistic experiences were universal. Perennialists tend to distinguish between the experience itself, and its post experience interpretation to make sense of the different views in world religions.

Some constructivists like Steven T. Katz meanwhile have argued against the common core thesis, and for either the view that every mystical experience contains at least some concepts (soft constructivism) or that they are strongly shaped and determined by one's religious ideas and culture (hard constructivism). In this view, the conceptual scheme of any mystic strongly shapes their experiences and because mystics from different religions have very different schemas, there cannot be any universal mystical experiences.

Religion and ethics

All religions argue for certain values and ideas of the moral Good. Non-monotheistic Indian traditions like Buddhism and Advaita Vedanta find the highest Good in nirvana or moksha which leads to release from suffering and the rounds of rebirth and morality is a means to achieve this, while for monotheistic traditions, God is the source or ground of all morality and heaven in the highest human good. The world religions also offer different conceptions of the source of evil and suffering in the world, that is, what is wrong with human life and how to solve and free ourselves from these dilemmas. For example, for Christianity, sin is the source of human problems, while for Buddhism, it is craving and ignorance.

A general question which philosophy of religion asks is what is the relationship, if any, between morality and religion. Brian Davies outlines four possible theses:

- Morality somehow requires religion. One example of this view is Kant's idea that morality should lead us to believe in a moral law, and thus to believe in an upholder of that law, that is, God.

- Morality is somehow included in religion, "The basic idea here is that being moral is part of what being religious means."

- Morality is pointless without religion, for one would have no reason to be moral without it.

- Morality and religion are opposed to each other. In this view, belief in a God would mean one would do whatever that God commands, even if it goes against morality. The view that religion and morality are often opposed has been espoused by atheists like Lucretius and Bertrand Russell as well as by theologians like Kierkegaard who argued for a 'teleological suspension of the ethical'.

Monotheistic religions who seek to explain morality and its relationship to God must deal with what is termed the Euthyphro dilemma, famously stated in the Platonic dialogue "Euthyphro" as: "Is the pious (τὸ ὅσιον, i.e. what is morally good) loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?" Those who hold that what is moral is so because it is what God commands are defending a version of the Divine command theory.

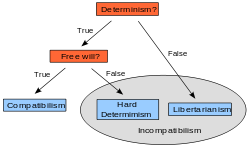

Another important topic which is widely discussed in Abrahamic monotheistic religious philosophy is the problem of human Free will and God's omniscience. God's omniscience could presumably include perfect knowledge of the future, leading to Theological determinism and thus possibly contradicting with human free will. There are different positions on this including libertarianism (free will is true) and Predestination.

Miracles

Belief in miracles and supernatural events or occurrences is common among world religions. A miracle is an event which cannot be explained by rational or scientific means. The Resurrection of Jesus and the Miracles of Muhammad are examples of miracles claimed by religions.

Skepticism towards the supernatural can be found in early philosophical traditions like the Indian Carvaka school and Greco-Roman philosophers like Lucretius. David Hume, who defined a miracle as "a violation of the laws of nature", famously argued against miracles in Of Miracles, Section X of An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding (1748). For Hume, the probability that a miracle hasn't occurred is always greater than the probability that it has because "as a firm and unalterable experience has established these laws [of nature], the proof against a miracle, from the very nature of the fact, is as entire as any argument from experience can possibly be imagined" (Enquiry. X. p. 173). Hume doesn't argue that a miracle is impossible, only that it is unreasonable to believe in any testimony of a miracle's occurrence, for evidence for the regularity of natural laws is much stronger than human testimony (which is often in error).

According to Rowe, there are two weaknesses with Hume's argument. First, there could be other forms of indirect evidence for the occurrence of a miracle that does not include testimony of someone's direct experience of it. Secondly, Rowe argues that Hume overestimates "the weight that should be given to past experience in support of some principle thought to be a law of nature." For it is a common occurrence that currently accepted ideas of natural laws are revised due to an observed exception but Hume's argument would lead one to conclude that these exceptions do not occur. Rowe adds that "It remains true, however, that a reasonable person will require quite strong evidence before believing that a law of nature has been violated. It is easy to believe the person who claimed to see water run downhill, but quite difficult to believe that someone saw water run uphill."

Another definition of a miracle is possible however, which is termed the Epistemic theory of miracles and was argued for by Spinoza and St. Augustine. This view rejects that a miracle is a transgression of natural laws, but is simply a transgression of our current understanding of natural law. In the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, Spinoza writes: "miracles are only intelligible as in relation to human opinions, and merely mean events of which the natural cause cannot be explained by a reference to any ordinary occurrence, either by us, or at any rate, by the writer and narrator of the miracle" (Tractatus p. 84). Similarly, R.F. Holland has defined miracle in a naturalistic way in a widely cited paper. For Holland, a miracle need only be an extraordinary and beneficial coincidence interpreted religiously.

Brian Davies notes that even if we can establish that a miracle has occurred, it is hard to see what this is supposed to prove. For it is possible that they arise due to agencies which are unusual and powerful, but not divine.

Afterlife

World religions put forth various theories which affirm life after death and different kinds of postmortem existence. This is often tied to belief in an immortal individual soul or self (Sanskrit: atman) separate from the body which survives death, as defended by Plato, Descartes, Monotheistic religions like Christianity and many Indian philosophers. This view is also a position on the mind body problem, mainly, dualism. This view then must show not only that dualism is true and that souls exist, but also that souls survive death. As Kant famously argued, the mere existence of a soul does not prove its immortality, for one could conceive that a soul, even if it is totally simple, could still fade away or lose its intensity. H. H. Price is one modern philosopher who has speculated at length about what it would be like to be a disembodied soul after death.

One major issue with soul beliefs is that since personhood is closely tied to one's physical body, it seems difficult to make sense of a human being existing apart from their body. A further issue is with continuity of personal identity, that is, it is not easy to account for the claim that the person that exists after bodily death is the same person that existed before.

Bertrand Russell put forth the general scientific argument against the afterlife as follows:

Persons are part of the everyday world with which science is concerned, and the conditions which determine their existence are discoverable...we know that the brain is not immortal, and that the organized energy of a living body becomes, as it were, demobilized at death and therefore not available for collective action. All the evidence goes to show that what we regard as our mental life is bound up with brain structure and organized bodily energy. Therefore it is rational to suppose that mental life ceases when bodily life ceases. The argument is only one of probability, but it is as strong as those upon which most scientific conclusions are based.

Contra Russell, J. M. E. McTaggart argues that people have no scientific proof that the mind is dependent on the body in this particular way. As Rowe notes, the fact that the mind depends on the functions of the body while one is alive is not necessarily proof that the mind will cease functioning after death just as a person trapped in a room while depending on the windows to see the outside world might continue to see even after the room ceases to exist.

Buddhism is one religion which, while affirming postmortem existence (through rebirth), denies the existence of individual souls and instead affirms a deflationary view of personal identity, termed not-self (anatta).

While physicalism has generally been seen as hostile to notions of an afterlife, this need not be the case. Abrahamic religions like Christianity have traditionally held that life after death will include the element of bodily resurrection. One objection to this view is that it seems difficult to account for personal continuity, at best, a resurrected body is a replica of the resurrected person not the same person. One response is the constitution view of persons, which says persons are constituted by their bodies and by a "first-person perspective", the capacity to think of oneself as oneself. In this view, what is resurrected is that first person perspective, or both the person's body and that perspective. An objection to this view is that it seems difficult to differentiate one person's first person perspective from another person's without reference to temporal and spatial relations. Peter van Inwagen meanwhile, offers the following theory:

Perhaps at the moment of each man's death, God removes his corpse and replaces it with a simulacrum which is what is burned or rots. Or perhaps God is not quite so wholesale as this: perhaps He removes for "safekeeping" only the "core person"—the brain and central nervous system—or even some special part of it. These are details. (van Inwagen 1992: 245–46)

This view shows how some positions on the nature of the afterlife are closely tied to and sometimes completely depend upon theistic positions. This close connection between the two views was made by Kant, who argued that one can infer an afterlife from belief in a just God who rewards persons for their adherence to moral law.

Other discussions on the philosophy of the afterlife deal with phenomena such as near death experiences, reincarnation research, and other parapsychological events and hinge on whether naturalistic explanations for these phenomena is enough to explain them or not. Such discussions are associated with philosophers like William James, Henry Sidgwick, C.D. Broad, and H.H. Price.

Diversity and pluralism

The issue of how one is to understand religious diversity and the plurality of religious views and beliefs has been a central concern of the philosophy of religion.

There are various philosophical positions regarding how one is to make sense of religious diversity, including exclusivism, inclusivism, pluralism, relativism, atheism or antireligion and agnosticism.

Religious exclusivism is the claim that only one religion is true and that others are wrong. To say that a religion is exclusivistic can also mean that salvation or human freedom is only attainable by the followers of one's religion. This view tends to be the orthodox view of most monotheistic religions, such as Christianity and Islam, though liberal and modernist trends within them might differ. William L Rowe outlines two problems with this view. The first problem is that it is easy to see that if this is true, a large portion of humanity is excluded from salvation and it is hard to see how a loving god would desire this. The second problem is that once we become acquainted with the saintly figures and virtuous people in other religions, it can be difficult to see how we could say they are excluded from salvation just because they are not part of our religion.

A different view is inclusivism, which is the idea that "one's own tradition alone has the whole truth but that this truth is nevertheless partially reflected in other traditions." An inclusivist might maintain that their religion is privileged, they can also hold that other religious adherents have fundamental truths and even that they will be saved or liberated. The Jain view of Anekantavada ('many-sidedness') has been interpreted by some as a tolerant view which is an inclusive acceptance of the partial truth value of non-Jain religious ideas. As Paul Dundas notes, the Jains ultimately held the thesis that Jainism is the final truth, while other religions only contain partial truths. Other scholars such as Kristin Beise Kiblinger have also argued that some of the Buddhist traditions include inclusivist ideas and attitudes.

In the modern Western study of religion, the work of Ninian Smart has also been instrumental in representing a more diverse understanding of religion and religious pluralism. Smart's view is that there are genuine differences between religions.

Pluralism is the view that all religions are equally valid responses to the divine and that they are all valid paths to personal transformation. This approach is taken by John Hick, who has developed a pluralistic view which synthesizes components of various religious traditions. Hick promotes an idea of a noumenal sacred reality which different religions provide us access to. Hick defines his view as "the great world faiths embody different perceptions and conceptions of, and correspondingly different responses to, the Real or the Ultimate." For Hick, all religions are true because they all allow us to encounter the divine reality, even if they have different deities and conceptions of it. Rowe notes that a similar idea is proposed by Paul Tillich's concept of Being-itself.

The view of perennialism is that there is a single or core truth or experience which is shared by all religions even while they use different terms and language to express it. This view is espoused by the likes of Aldous Huxley, the thinkers of the Traditionalist School as well as Neo-Vedanta.

Yet another way of responding to the conflicting truth claims of religions is Relativism. Joseph Runzo., one of its most prominent defenders, has argued for henofideism which states that the truth of a religious worldview is relative to each community of adherents. Thus while religions have incompatible views, each one is individually valid as they emerge from individual experiences of a plurality of phenomenal divine realities. According to Runzo, this view does not reduce the incompatible ideas and experiences of different religions to mere interpretations of the Real and thus preserves their individual dignity.

Another response to the diversity and plurality of religious beliefs and deities throughout human history is one of skepticism towards all of them (or even antireligion), seeing them as illusions or human creations which serve human psychological needs. Sigmund Freud was a famous proponent of this view, in various publications such as The Future of an Illusion (1927) and Civilization and Its Discontents (1930). According to Freud, "Religion is an illusion and it derives its strength from the fact that it falls in with our instinctual desires."

While one can be skeptical towards the claims of religion, one need not be hostile towards religion. Don Cupitt is one example of someone who, while disbelieving in the metaphysical and cosmological claims of his religion, holds that one can practice it with a "non-realist" perspective which sees religious claims as human inventions and myths to live by.

Religious language

The question of religious language and in what sense it can be said to be meaningful has been a central issue of the philosophy of religion since the work of the Vienna circle, a group of philosophers who, influenced by Wittgenstein, put forth the theory of Logical positivism. Their view was that religious language, such as any talk of God cannot be verified empirically and thus was ultimately meaningless. This position has also been termed theological noncognitivism. A similar view can be seen in David Hume's An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, where he famously wrote that any work which did not include either (1) abstract reasoning on quantity or number or (2) reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence was "nothing but sophistry and illusion".

In a similar vein, Antony Flew, questioned the validity of religious statements because they do not seem to be falsifiable, that is, religious claims do not seem to allow any counter evidence to count against them and thus they seem to be lacking in content. While such arguments were popular in the 1950s and 60s, the verification principle and falsifiability as a criterion for meaning are no longer as widely held. The main problem with verificationism is that it seems to be self refuting, for it is a claim which does not seem to be supported by its own criterion.

As noted by Brian Davies, when talking about God and religious truths, religious traditions tend to resort to metaphor, negation and analogy. The via negativa has been defended by thinkers such as Maimonides who denied that positive statements about God were helpful and wrote: "you will come nearer to the knowledge and comprehension of God by the negative attributes." Similar approaches based on negation can be seen in the Hindu doctrine of Neti neti and the Buddhist philosophy of Madhyamaka.

Wittgenstein's theory of language games also shows how one can use analogical religious language to describe God or religious truths, even if the words one is using do not in this case refer to their everyday sense, i.e. when we say God is wise, we do not mean he is wise in the same sense that a person is wise, yet it can still make sense to talk in this manner. However, as Patrick Sherry notes, the fact that this sort of language may make sense does not mean that one is warranted in ascribing these terms to God, for there must be some connection between the relevant criteria we use in ascribing these terms to conventional objects or subjects and to God. As Chad Meister notes though, for Wittgenstein, a religion's language game need not reflect some literal picture of reality (as a picture theory of meaning would hold) but is useful simply because its ability to "reflect the practices and forms of life of the various religious adherents." Following Wittgenstein, philosophers of religion like Norman Malcolm, B. R. Tilghman, and D. Z. Phillips have argued that instead of seeing religious language as referring to some objective reality, we should instead see it as referring to forms of life. This approach is generally termed non-realist.

Against this view, realists respond that non-realism subverts religious belief and the intelligibility of religious practice. It is hard to see for example, how one can pray to a God without believing that they really exist. Realists also argue that non-realism provides no normative way to choose between competing religions.

Analytic philosophy of religion

In Analytic Philosophy of Religion, James Franklin Harris noted that

analytic philosophy has been a very heterogeneous 'movement'.... some forms of analytic philosophy have proven very sympathetic to the philosophy of religion and have actually provided a philosophical mechanism for responding to other more radical and hostile forms of analytic philosophy.

As with the study of ethics, early analytic philosophy tended to avoid the study of philosophy of religion, largely dismissing (as per the logical positivists view) the subject as part of metaphysics and therefore meaningless. The collapse of logical positivism renewed interest in philosophy of religion, prompting philosophers like William Alston, John Mackie, Alvin Plantinga, Robert Merrihew Adams, Richard Swinburne, and Antony Flew not only to introduce new problems, but to re-open classical topics such as the nature of miracles, theistic arguments, the problem of evil, the rationality of belief in God, concepts of the nature of God, and many more.

Plantinga, Mackie and Flew debated the logical validity of the free will defense as a way to solve the problem of evil. Alston, grappling with the consequences of analytic philosophy of language, worked on the nature of religious language. Adams worked on the relationship of faith and morality. Analytic epistemology and metaphysics has formed the basis for a number of philosophically-sophisticated theistic arguments, like those of the reformed epistemologists like Plantinga.

Analytic philosophy of religion has also been preoccupied with Ludwig Wittgenstein, as well as his interpretation of Søren Kierkegaard's philosophy of religion. Using first-hand remarks (which would later be published in Philosophical Investigations, Culture and Value, and other works), philosophers such as Peter Winch and Norman Malcolm developed what has come to be known as contemplative philosophy, a Wittgensteinian school of thought rooted in the "Swansea tradition" and which includes Wittgensteinians such as Rush Rhees, Peter Winch and D. Z. Phillips, among others. The name "contemplative philosophy" was first coined by D. Z. Phillips in Philosophy's Cool Place, which rests on an interpretation of a passage from Wittgenstein's "Culture and Value." This interpretation was first labeled, "Wittgensteinian Fideism," by Kai Nielsen but those who consider themselves Wittgensteinians in the Swansea tradition have relentlessly and repeatedly rejected this construal as a caricature of Wittgenstein's considered position; this is especially true of D. Z. Phillips. Responding to this interpretation, Kai Nielsen and D.Z. Phillips became two of the most prominent philosophers on Wittgenstein's philosophy of religion.