Religious violence covers phenomena in which religion is either the subject or the object of violent behavior. All the religions of the world contain narratives, symbols, and metaphors of violence and war. Religious violence is violence

that is motivated by, or in reaction to, religious precepts, texts, or

the doctrines of a target or an attacker. It includes violence against

religious institutions, people, objects, or events. Religious violence

does not exclusively include acts which are committed by religious

groups, instead, it includes acts which are committed against religious

groups.

"Violence" is a very broad concept which is difficult to define because it is used against both human and non-human objects.

Furthermore, the term can denote a wide variety of experiences such as

blood shedding, physical harm, forcing against personal freedom,

passionate conduct or language, or emotions such as fury and passion.

"Religion" is a complex and problematic modern western concept. Though there is no scholarly consensus over what a religion is,

today, religion is generally considered an abstraction which entails

beliefs, doctrines, and sacred places. The link between religious belief

and behavior is problematic. Decades of anthropological, sociological,

and psychological research have all proven the falsehood of the

assumption that behaviors directly follow from religious beliefs and

values because people's religious ideas are fragmented, loosely

connected, and context-dependent just like all other domains of culture

and life.

In general, religions, ethical systems, and societies rarely promote

violence as an end in itself since violence is universally undesirable.

At the same time, there is a universal tension between the general

desire to avoid violence and the acceptance of justifiable uses of

violence to prevent a "greater evil" that permeates all cultures.

Religious violence, like all forms of violence, is a cultural process which is context-dependent and very complex.

Oversimplifications of "religion" and "violence" often lead to

misguided understandings of causes for why some people commit acts of

violence and why most people never commit such acts in the first place. Violence is perpetrated for a wide variety of ideological

reasons and religion is generally only one of many contributing social

and political factors that can lead to unrest. Studies of supposed cases

of religious violence often conclude that violence is strongly driven

by ethnic animosities rather than by religious worldviews.

Due to the complex nature of religion and violence and the complex

relationship which exists between them, it is normally unclear if

religion is a significant cause of violence.

History of the concept of religion

Religion is a modern Western concept.

The compartmentalized concept of religion, where religious things were

separated from worldly things, was not used before the 1500s. Furthermore, parallel concepts are not found in many cultures and there is no equivalent term for "religion" in many languages. Scholars have found it difficult to develop a consistent definition, with some giving up on the possibility of a definition and others rejecting the term entirely. Others argue that regardless of its definition, it is not appropriate to apply it to non-Western cultures.

The modern concept of "religion" as an abstraction which entails

distinct sets of beliefs or doctrines is a recent invention in the

English language since such usage began with texts from the 17th century

due to the splitting of Christendom during the Protestant Reformation and more prevalent colonization or globalization in the age of exploration which involved contact with numerous foreign and indigenous cultures with non-European languages.

Ancient sacred texts like the Bible and the Quran

did not have a concept of religion in their original languages and

neither did their authors or the cultures to which they belonged. It was in the 19th century that the terms "Buddhism", "Hinduism", "Taoism", and "Confucianism" first emerged.

There is no precise equivalent of "religion" in Hebrew, and Judaism does not draw clear distinctions between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities.

Definition of violence

Violence

is difficult to define because the term is a complicated concept which

broadly carries descriptive and evaluative components which range from

harming non-human objects to human self-harm.

Ralph Tanner cites the definition of violence in the Oxford English

Dictionary as "far beyond (the infliction of) pain and the shedding of

blood." He argues that, although violence clearly encompasses injury to

persons or property, it also includes "the forcible interference in

personal freedom, violent or passionate conduct or language (and)

finally passion or fury."

Similarly, Abhijit Nayak writes:

The word "violence" can be defined to extend far beyond pain and

shedding blood. It carries the meaning of physical force, violent

language, fury, and, more importantly, forcible interference.

Terence Fretheim writes:

For many people, ... only physical violence truly qualifies as

violence. But, certainly, violence is more than killing people, unless

one includes all those words and actions that kill people slowly. The

effect of limitation to a “killing fields” perspective is the widespread

neglect of many other forms of violence. We must insist that violence

also refers to that which is psychologically destructive, that which

demeans, damages, or depersonalizes others. In view of these

considerations, violence may be defined as follows: any action, verbal

or nonverbal, oral or written, physical or psychical, active or passive,

public or private, individual or institutional/societal, human or

divine, in whatever degree of intensity, that abuses, violates, injures,

or kills. Some of the most pervasive and most dangerous forms of

violence are those that are often hidden from view (against women and

children, especially); just beneath the surface in many of our homes,

churches, and communities is abuse enough to freeze the

blood. Moreover, many forms of systemic violence often slip past our

attention because they are so much a part of the infrastructure of life

(e.g., racism, sexism, ageism).

Relationship between religion and violence

According

to Steve Clarke, "currently available evidence does not allow us to

determine whether religion is, or is not, a significant cause of

violence." He lists multiple problems that make it impossible to

establish a causal relationship such as difficulties in distinguishing

motive/pretext and inability to verify if they would necessarily lead to

any violent action, the lack of consensus of definitions of both

violence and religion among scholars, and the inability to see if the

presence of religion actually adds or subtracts from general levels of

violence since no society without religion has ever existed to compare

with.

Charles Selengut characterizes the phrase "religion and violence"

as "jarring", asserting that "religion is thought to be opposed to

violence and a force for peace and reconciliation." He acknowledges,

however, that "the history and scriptures of the world's religions tell

stories of violence and war even as they speak of peace and love."

According to Matthew Rowley, three hundred contributing causes of

religious violence have been discussed by some scholars, however, he

states that "violence in the name of God is a complex phenomenon and

oversimplification further jeopardizes peace because it obscures many of

the causal factors."

In another piece, Matthew Rowley lists 15 ways to address the

complexity of violence, both secular and religious, and he also states

that secular narratives of religious violence tend to be erroneous or

exaggerated due to their over simplification of religious people, their

oversimplification of religious people's beliefs, their thinking which

is based on false dichotomies, and their ignorance of complex secular

causes of supposed "religious violence". He also states that when one is

discussing religious violence, he or she should also note that the

overwhelming majority of religious people do not get inspired to engage

in violence.

Similarly, Ralph Tanner describes the combination of religion and

violence as "uncomfortable", asserting that religious thinkers

generally avoid the conjunction of the two and argue that religious

violence is "only valid in certain circumstances which are invariably

one-sided".

Michael Jerryson argues that scholarship on religion and violence

sometimes overlooks non-Abrahamic religions. This tendency leads to

considerable problems, one of which is the support of faulty

associations. For example, he finds a persistent global pattern of

alignment in which religions such as Islam are viewed as causes of

violence and religions such as Buddhism are viewed as causes of peace.

In many instances of political violence, religion tends to play a central role. This is especially true of terrorism,

in which acts of violence are committed against unarmed noncombatants

in order to inspire fear and achieve political goals. Terrorism expert Martha Crenshaw

suggests that religion is just a mask which is used by political

movements which seek to draw attention to their causes and gain support.

Crenshaw outlines two approaches when she observes religious violence

in order to view its underlying mechanisms.

One approach, called the instrumental approach, sees religious violence

as acting as a rational calculation to achieve some political end.

Increasing the costs of performing such violence will help curb it.

Crenshaw's alternate approach sees religious violence stemming from the

organizational structure of religious communities, with the heads of

these communities acting as political figureheads. Crenshaw suggests

that threatening the internal stability of these organizations (perhaps

by offering them a nonviolent alternative) will dissuade religious

organizations from performing political violence. A third approach sees

religious violence as the result of community dynamics rather than a

religious duty. Systems of meanings

which are developed within these communities allow religious

interpretations to justify violence, so acts like terrorism occur

because people are part of communities of violence.

In this way, religious violence and terrorism are performances which

are designed to inspire an emotional reaction from both those in the

community and those outside of it.

Hector Avalos

argues that religions cause violence over four scarce resources: access

to divine will, knowledge, primarily through scripture; sacred space;

group privileging; and salvation. Not all religions have or use these

four resources. He believes that religious violence is particularly

untenable because these resources are never verifiable and, unlike

claims to scarce resources such as water or land, it cannot be

adjudicated objectively.

Regina Schwartz

argues that all monotheistic religions are inherently violent because

of an exclusivism that inevitably fosters violence against those that

are considered outsiders.

Lawrence Wechsler asserts that Schwartz isn't just arguing that

Abrahamic religions have a violent legacy, she is arguing that their

legacy is genocidal in nature.

Challenges to the view that religions are violent

Behavioral studies

Decades

of research which was conducted by social scientists have established

that "religious congruence" (the assumption that religious beliefs and

values are tightly integrated in an individual's mind or that religious

practices and behaviors follow directly from religious beliefs or that

religious beliefs are chronologically linear and stable across different

contexts) is actually rare. People's religious ideas are fragmented,

loosely connected, and context-dependent, as in all other domains of

culture and in life. The beliefs, affiliations, and behaviors of any

individual are complex activities that have many sources including

culture.

Myth of religious violence

Others

such as William Cavanaugh have argued that it is unreasonable to

attempt to differentiate "religious violence" from "secular violence" by

classifying them as separate categories of violence. Cavanaugh asserts

that "the idea that religion has a tendency to promote violence is part

of the conventional wisdom of Western societies and it underlies many of

our institutions and policies, from limits on the public role of

churches to efforts to promote liberal democracy in the Middle East."

Cavanaugh challenges this conventional wisdom, arguing that there is a

"myth of religious violence", basing his argument on the assertion that

"attempts to separate religious and secular violence are incoherent".

Cavanaugh asserts:

- Religion is not a universal and transhistorical phenomenon. What

counts as "religious" or "secular" in any context is a function of

configurations of power both in the West and lands colonized by the

West. The distinctions of "Religious/Secular" and "Religious/Political"

are modern Western inventions.

- The invention of the concept of "religious violence" helps the West

reinforce superiority of Western social orders to "nonsecular" social

orders, namely Muslims at the time of publication.

- The concept of "religious violence" can be and is used to legitimate violence against non-Western "Others".

- Peace depends on a balanced view of violence and recognition that

so-called secular ideologies and institutions can be just as prone to

absolutism, divisiveness, and irrationality.

Jeffrey Russell argues that numerous cases of supposed acts of religious violence such as the Thirty Years War, the French Wars of Religion, the Protestant-Catholic conflict in Ireland, the Sri Lankan Civil War, and the Rwandan Civil War were all primarily motivated by social, political, and economic issues rather than religion.

John Morreall and Tamara Sonn have argued that all cases of

violence and war include social, political, and economic dimensions.

Since there is no consensus on definitions of "religion" among scholars

and since there is no way to isolate "religion" from the rest of the

more likely motivational dimensions, it is incorrect to label any

violent event as "religious". They state that since dozens of examples exist from the European wars of religion

that show that people from the same religions fought each other and

that people from different religions became allies during these

conflicts, the motivations for these conflicts were not about religion.

Jeffrey Burton Russell has argued that the fact that these wars of

religion ended after rulers agreed to practice their religions in their

own territories, means that the conflicts were more related to political

control than about people's religious views.

According to Karen Armstrong, so-called religious conflicts such as the Crusades, the Spanish Inquisition,

and the European wars of religion, were all deeply political conflicts

at their cores, rather than religious ones. Especially since people from

different faiths constantly became allies and fought against each other

in no consistent fashion. She states that the Western concept of the

separation of church and state, which was first advocated by the

Reformer Martin Luther,

laid a foundation for viewing religion and society as being divided

when in reality, religion and society were intermixed to the point that

no one made such a distinction nor was there a defining cut between such

experiences in the past. During the Enlightenment,

religion began to be seen as an individualistic and private thing

despite the fact that modern secular ideals like the equality of all

human beings, intellectual and political liberty were things that were

historically promoted in a religious idiom in the past.

Anthropologist Jack David Eller asserts that religion is not

inherently violent, arguing "religion and violence are clearly

compatible, but they are not identical." He asserts that "violence is

neither essential to nor exclusive to religion" and that " virtually

every form of religious violence has its nonreligious corollary."

Moreover, he argues that religion "may be more a marker of the

[conflicting] groups than an actual point of contention between them".

John Teehan takes a position that integrates the two opposing sides of

this debate. He describes the traditional response in defense of

religion as "draw(ing) a distinction between the religion and what is

done in the name of that religion or its faithful." Teehan argues, "this

approach to religious violence may be understandable but it is

ultimately untenable and prevents us from gaining any useful insight

into either religion or religious violence." He takes the position that

"violence done in the name of religion is not a perversion of religious

belief... but flows naturally from the moral logic inherent in many

religious systems, particularly monotheistic religions...." However,

Teehan acknowledges that "religions are also powerful sources of

morality." He asserts, "religious morality and religious violence both

spring from the same source, and this is the evolutionary psychology

underlying religious ethics."

Historians such as Jonathan Kirsch

have made links between the European inquisitions, for example, and

Stalin's persecutions in the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, McCarthy

blacklists, and other secular events as being the same type of

phenomenon as the inquisitions.

Others, such as Robert Pape,

a political scientist who specializes in suicide terrorism, have made a

case for secular motivations and reasons as being foundations of most

suicide attacks that are oftentimes labeled as "religious".

Pape compiled the first complete database of every documented suicide

bombing during 1980–2003. He argues that the news reports about suicide attacks are profoundly misleading — "There is little connection between suicide terrorism and Islamic fundamentalism,

or any one of the world's religions". After studying 315 suicide

attacks carried out over the last two decades, he concludes that suicide

bombers' actions stem fundamentally from political conflict, not

religion.

Secularism as a response

Byron

Bland asserts that one of the most prominent reasons for the "rise of

the secular in Western thought" was the reaction against the religious

violence of the 16th and 17th centuries. He asserts that "(t)he secular

was a way of living with the religious differences that had produced so

much horror. Under secularity, political entities have a warrant to make

decisions independent from the need to enforce particular versions of

religious orthodoxy. Indeed, they may run counter to certain strongly

held beliefs if made in the interest of common welfare. Thus, one of the

important goals of the secular is to limit violence." William T. Cavanaugh

writes that what he calls "the myth of religious violence" as a reason

for the rise of secular states may be traced to earlier philosophers,

such as Spinoza, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, and Voltaire. Cavanaugh delivers a detailed critique of this idea in his 2009 book The Myth of Religious Violence: Secular Ideology and the Roots of Modern Conflict.

Secular violence

Janet Jakobsen states that "just as religion and secularism are

relationally defined terms - terms that depend on each other - so also

the legitimization of violence through either religious or secular

discourse is also relational."

She states that the idea that "religion kills" is used to legitimate

secular violence, and that, similarly, the idea that "secularism kills"

is used to legitimate religious violence.

According to John Carlson, critics who are skeptical of "religious

violence" contend that excessive attention is often paid to acts of

religious violence compared to acts of secular violence, and that this

leads to a false essentializing of both religion as being prone to

violence and the secular as being prone to peace.

According to Janet Jakobsen, secularism and modern secular states are

much more violent than religion, and modern secular states in particular

are usually the source of most of the world's violence.

Carlson states that by focusing on the destructive capacity of

government, Jakobsen "essentializes another category - the secular state

- even as she criticizes secular governments that essentialize

religion's violent propensities". Tanner states that secular regimes and leaders have used violence to promote their own agendas.

Violence committed by secular governments and people, including the

anti-religious, have been documented including violence or persecutions

focused on religious believers and those who believe in the

supernatural. In the 20th century, estimates state that over 25 million Christians died from secular antireligious violence worldwide.

Religions have been persecuted more in the past 100 years than at any other time in history.

According to Geoffrey Blainey, atrocities have occurred under all

ideologies, including in nations which were strongly secular such as the

Soviet Union, China, and Cambodia. Talal Asad, an anthropologist, states that equating institutional religion

with violence and fanaticism is incorrect and that devastating

cruelties and atrocities done by non-religious institutions in the 20th

century should not be overlooked. He also states that nationalism has

been argued as being a secularized religion.

Abrahamic religions

Hector Avalos

argues that, because religions claim to have divine favor for

themselves, both over and against other groups, this sense of

self-righteousness leads to violence because conflicting claims of

superiority, based on unverifiable appeals to God, cannot be objectively

adjudicated.

Similarly, Eric Hickey writes, "the history of religious violence

in the West is as long as the historical record of its three major

religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam,

with their mutual antagonisms and their struggles to adapt and survive

despite the secular forces that threaten their continued existence."

Regina Schwartz argues that all monotheistic religions, including Christianity,

are inherently violent because of their exclusivism which inevitably

fosters violence against those who are considered outsiders. Lawrence Wechsler asserts that Schwartz isn't just arguing that Abrahamic religions have a violent legacy, instead, she is arguing that their legacy is actually genocidal in nature.

Christianity

Before the 11th century, Christians had not developed the doctrine of "Holy war", the belief that fighting itself might be considered a penitential and spiritually meritorious act. Throughout the Middle Ages, force could not be used to propagate religion. For the first three centuries of Christianity, the Church taught the pacifism of Jesus and notable church fathers such as Justin Martyr, Tertullian, Origen, and Cyprian of Carthage even went as far as arguing against joining the military or using any form of violence against aggressors. In the 4th century, St. Augustine

developed a "Just War" concept, whereby limited uses of war would be

considered acceptable in order to preserve the peace and retain

orthodoxy if it was waged: for defensive purposes, ordered by an

authority, had honorable intentions, and produced minimal harm. However,

the criteria he used was already developed by Roman thinkers in the

past and "Augustine's perspective was not based on the New Testament." St. Augustine's "Just War" concept was widely accepted, however, warfare was not regarded as virtuous in any way.

Expression of concern for the salvation of those who killed enemies in

battle, regardless of the cause for which they fought, was common. In the medieval period which began after the fall of Rome,

there were increases in the level of violence due to political

instability. By the 11th century, the Church condemned this violence and

warring by introducing: the "Peace of God" which prohibited attacks on

clergy, pilgrims, townspeople, peasants and property; the "Truce of God"

which banned warfare on Sundays, Fridays, Lent, and Easter;

and it imposed heavy penances on soldiers for killing and injuring

others because it believed that the shedding of other people's blood was

the same as shedding the blood of Christ.

During the 9th and 10th centuries, multiple invasions occurred in

some regions in Europe and these invasions lead them to form their own

armies in order to defend themselves and by the 11th century, this

slowly lead to the emergence of the Crusades, the concept of "holy war",

and terminology such as "enemies of God".

By the time of the Crusades, "Despite all the violence during this

period, the majority of Christians were not active participants but were

more often its victims" and groups which used nonviolent means to

peacefully dialogue with Muslims were established, like the Franciscans.

Today, the relationship between Christianity and violence

is the subject of controversy because one view advocates the belief

that Christianity advocates peace, love and compassion despite the fact

that in certain instances, its adherents have also resorted to violence.

Peace, compassion and forgiveness of wrongs done by others are key

elements of Christian teaching. However, Christians have struggled since

the days of the Church fathers with the question of when the use of force is justified (e.g. the Just war theory of Saint Augustine). Such debates have led to concepts such as just war theory. Throughout history, certain teachings from the Old Testament, the New Testament and Christian theology have been used to justify the use of force against heretics, sinners and external enemies. Heitman and Hagan identify the Inquisitions, Crusades, wars of religion, and antisemitism as being "among the most notorious examples of Christian violence". To this list, Mennonite theologian J. Denny Weaver adds "warrior popes, support of capital punishment, corporal punishment under the guise of 'spare the rod spoil the child,' justifications of slavery, world-wide colonialism under the guise of converting people to Christianity, the systemic violence against women who are subjected to the rule of men."

Weaver employs a broader definition of violence that extends the

meaning of the word to cover "harm or damage", not just physical

violence per se. Thus, under his definition, Christian violence includes

"forms of systemic violence such as poverty, racism, and sexism".

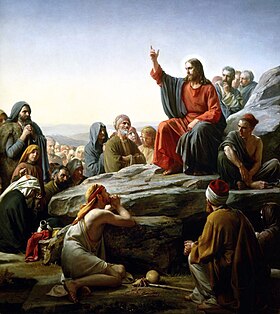

Christian theologians point to a strong doctrinal and historical imperative against violence that exists within Christianity, particularly Jesus' Sermon on the Mount,

which taught nonviolence and "love of enemies". For example, Weaver

asserts that Jesus' pacifism was "preserved in the justifiable war

doctrine which declares that all war is sin even when it is occasionally

declared to be a necessary evil, and in the prohibition of fighting by

monastics and clergy as well as in a persistent tradition of Christian pacifism".

Between 1420 and 1431 the

Hussite heretics fended off 5 anti-Hussite

Crusades ordered by the Pope.

Many authors highlight the ironical contradiction between

Christianity's claims to be centered on "love and peace" while, at the

same time, harboring a "violent side". For example, Mark Juergensmeyer

argues: "that despite its central tenets of love and peace,

Christianity—like most traditions—has always had a violent side. The

bloody history of the tradition has provided images as disturbing as

those provided by Islam,

and violent conflict is vividly portrayed in the Bible. This history

and these biblical images have provided the raw material for

theologically justifying the violence of contemporary Christian groups.

For example, attacks on abortion clinics

have been viewed not only as assaults on a practice that Christians

regard as immoral, but also as skirmishes in a grand confrontation

between forces of evil and good that has social and political

implications.", sometimes referred to as spiritual warfare. The statement attributed to Jesus "I come not to bring peace, but to bring a sword" has been interpreted by some as a call to arms to Christians.

Maurice Bloch

also argues that the Christian faith fosters violence because the

Christian faith is a religion, and religions are violent by their very

nature; moreover, he argues that religion and politics are two sides of

the same coin—power.

Others have argued that religion and the exercise of force are deeply

intertwined, but they have also stated that religion may pacify, as well

as channel and heighten violent impulses

In response to the view that Christianity and violence are

intertwined, Miroslav Volf and J. Denny Weaver reject charges that

Christianity is a violent religion, arguing that certain aspects of

Christianity might be misused to support violence but that a genuine

interpretation of its core elements would not sanction human violence

but would instead resist it. Among the examples that are commonly used

to argue that Christianity is a violent religion, J. Denny Weaver lists

"(the) Crusades,

the multiple blessings of wars, warrior popes, support of capital

punishment, corporal punishment under the guise of 'spare the rod and

spoil the child,' justifications of slavery, world-wide colonialism in

the name of converting people to Christianity, the systemic violence

against women who are subjected to the rule of men." Weaver

characterizes the counter-argument as focusing on "Jesus, the beginning

point of Christian faith,... whose Sermon on the Mount taught

nonviolence and love of enemies,; who nonviolently faced his death at

the hands of his accusers; whose nonviolent teaching inspired the first

centuries of pacifist Christian history and was subsequently preserved

in the justifiable war doctrine

that declares that all war is sin even when it is occasionally declared

to be a necessary evil, and in the prohibition of fighting by monastics

and clergy as well as in a persistent tradition of Christian pacifism."

Miroslav Volf

acknowledges the fact that "many contemporaries see religion as a

pernicious social ill that needs aggressive treatment rather than

medicine from which a cure is expected." However, Volf contests the

claim that "(the) Christian faith, as one of the major world religions,

predominantly fosters violence." Instead of this negative assessment,

Volf argues that Christianity "should be seen as a contributor to more

peaceful social environments."

Volf examines the question of whether or not Christianity fosters

violence, and he has identified four main arguments which claim that it

does: that religion by its nature is violent, which occurs when people

try to act as "soldiers of God"; that monotheism entails violence,

because a claim of universal truth divides people into "us versus them";

that creation, as in the Book of Genesis, is an act of violence; and the argument that the intervention of a "new creation", as in the Second Coming, generates violence.

Writing about the latter, Volf says: "Beginning at least with

Constantine's conversion, the followers of the Crucified have

perpetrated gruesome acts of violence under the sign of the cross. Over

the centuries, the seasons of Lent and Holy Week were, for the Jews, times of fear and trepidation; Christians have perpetrated some of the worst pogroms as they remembered the crucifixion of Christ, for which they blamed the Jews. Muslims also associate the cross with violence; crusaders' rampages were undertaken under the sign of the cross."

In each case, Volf concluded that the Christian faith was misused in

order to justify violence. Volf argues that "thin" readings of

Christianity might be used mischievously to support the use of violence.

He counters, however, by asserting that "thick" readings of

Christianity's core elements will not sanction human violence, instead,

they will resist it.

Volf asserts that Christian churches suffer from a "confusion of

loyalties". He asserts that "rather than the character of the Christian

faith itself, a better explanation as to why Christian churches are

either impotent in the face of violent conflicts or are active

participants in them is derived from the proclivities of its adherents

which are at odds with the character of the Christian faith." Volf

observes that "(although) they are explicitly giving ultimate allegiance

to the Gospel of Jesus Christ, many Christians in fact seem to have an

overriding commitment to their respective cultures and ethnic groups."

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has an early history of violence. It was motivated by Anti-Mormonism and began with the religious persecution of the Church

by well respected citizens, law enforcement, and government officials.

Ultimately, this persecution lead to several historically well-known

acts of violence. These ranged from attacks on early members, such as

the Haun's Mill massacre following the Mormon Extermination Order to one of the most controversial and well-known cases of retaliation violence, the Mountain Meadows massacre.

This was the result of an unprovoked response to religious persecution

whereby an innocent party which was traveling through Church occupied

territory was attacked on 11 September 1857.

Islam

Islam has been associated with violence in a variety of contexts, especially in the context of Jihad. In Arabic, the word jihād

translates into English as "struggle". Jihad appears in the Qur'an and

frequently in the idiomatic expression "striving in the way of Allah (al-jihad fi sabil Allah)".

The context of the word can be seen in its usage in Arabic translations

of the New Testament such as in 2 Timothy 4:7 where St. Paul expresses

keeping the faith after many struggles. A person engaged in jihad is called a mujahid; the plural is mujahideen. Jihad is an important religious duty for Muslims. A minority among the Sunni scholars sometimes refer to this duty as the sixth pillar of Islam, though it occupies no such official status. In Twelver Shi'a Islam, however, Jihad is one of the ten Practices of the Religion.

For some the Quran seem to endorse unequivocally to violence. On the other hand, some scholars argue that such verses of the Quran are interpreted out of context.

According to a study from Gallup, most Muslims understand the

word "Jihad" to mean individual struggle, not something violent or

militaristic.

Muslims use the word in a religious context to refer to three types of

struggles: an internal struggle to maintain faith, the struggle to

improve the Muslim society, or the struggle in a holy war. The prominent British orientalist Bernard Lewis argues that in the Qur'an and the hadith jihad implies warfare in the large majority of cases. In a commentary of the hadith Sahih Muslim, entitled al-Minhaj, the medieval Islamic scholar Yahya ibn Sharaf al-Nawawi stated that "one of the collective duties of the community as a whole (fard kifaya)

is to lodge a valid protest, to solve problems of religion, to have

knowledge of Divine Law, to command what is right and forbid wrong

conduct".

Islam has a history of nonviolence and negotiation when dealing with

conflicts. For instance, early Muslims experienced 83 conflicts with

non-Muslims and only 4 of these ended up in armed conflict.

Terrorism and Islam

In western societies the term jihad is often translated as "holy war". Scholars of Islamic studies often stress the fact that these two terms are not synonymous. Muslim authors, in particular, tend to reject such an approach, stressing the non-militant connotations of the word.

Islamic terrorism refers to terrorism that is engaged in by Muslim groups or individuals who are motivated by either politics, religion or both. Terrorist acts have included airline hijacking, kidnapping, assassination, suicide bombing, and mass murder.

The tension reached a climax on 11 September 2001 when Islamic terrorists flew hijacked commercial airplanes into the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. The "War on Terror" has triggered anti-Muslim sentiments within most western countries and throughout the rest of the world. Al-Qaeda is one of the most well-known Islamic extremist groups, created by Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden. Al-Qaeda's goal is to spread the "purest" form of Islam and Islamic law.

Based on his interpretation of the Quran, bin Laden needed to do "good"

by inflicting terror upon millions of people. Following the terrorist

attacks on 11 September, bin Laden praised the suicide bombers in his statement: "the great action you did which was first and foremost by the grace of Allah.

This is the guidance of Allah and the blessed fruit of jihad." In

contrast, echoing the overwhelming majority of people who interpreted

these events, President Bush

said on 11 September, "Freedom itself was attacked this morning by a

faceless coward. ... And freedom will be defended. Make no mistake, the

United States will hunt down and punish those responsible for these

cowardly acts."

Controversies surrounding the subject include disagreements over

whether terrorist acts are self-defense or aggression, national

self-determination or Islamic supremacy; whether Islam can ever condone

the targeting of non-combatants; whether some attacks described as

Islamic terrorism are merely terrorist acts committed by Muslims or

terrorist acts motivated by nationalism; whether Wahhabism

are at the root of Islamic terrorism, or simply one cause of it; how

much support for Islamic terrorism exists in the Muslim world and whether support of terrorism is only a temporary phenomenon, a "bubble", now fading away.

Judaism

As the religion of the Jews, who are also known as Israelites, Judaism is based on the Torah and the Tanakh, which is also referred to as the Hebrew Bible, and it guides its adherents on how to live, die, and fight via the 613 commandments which are referred to as the 613 Mitzvahs, the most famous of which are the Ten Commandments, one of which is the commandment You shall not murder.

The Torah also lists instances and circumstances which require

its adherents to go to war and kill their enemies. Such a war is usually

referred to as a Milkhemet Mitzvah, a "compulsory war" which is obligated by the Torah or God, or a Milkhemet Reshut a "voluntary war".

Criticism

Burggraeve and Vervenne describe the Old Testament

as being full of violence and they also cite it as evidence for the

existence of both a violent society and a violent god. They write that,

"(i)n numerous Old Testament texts the power and glory of Israel's God

is described in the language of violence." They assert that more than

one thousand passages refer to Yahweh

as acting violently or supporting the violence of humans and they also

assert that more than one hundred passages involve divine commands to

kill humans.

On the basis of these passages in the Old Testament, some Christian churches and theologians argue that Judaism

is a violent religion and the god of Israel is a violent god. Reuven

Firestone asserts that these assertions are usually made in the context

of claims that Christianity is a religion of peace and the god of

Christianity is one who only expresses love.

Other views

Some

scholars such as Deborah Weissman readily acknowledge the fact that

"normative Judaism is not pacifist" and "violence is condoned in the

service of self-defense."However, the Talmud prohibits violence of any kind towards one's neighbour.

J. Patout Burns asserts that, although Judaism condones the use of

violence in certain cases, Jewish tradition clearly posits the principle

of minimization of violence. This principle can be stated as

"(wherever) Jewish law allows violence to keep an evil from occurring,

it mandates that the minimal amount of violence must be used in order to

accomplish one's goal."

The love and pursuit of peace, as well as laws which require the eradication of evil, sometimes by the use of violent means, co-exist in the Jewish tradition.

The Hebrew Bible contains instances of religiously mandated wars which often contain explicit instructions from God to the Israelites to exterminate other tribes, as in Deuteronomy 7:1–2 or Deuteronomy 20:16–18. Examples include the story

of the Amalekites (Deuteronomy 25:17–19, 1 Samuel 15:1–6), the story of the Midianites (Numbers 31:1–18), and the battle of Jericho (Joshua 6:1–27).

Judging biblical wars

The biblical wars of extermination have been characterized as "genocide" by several authorities, because the Torah

states that the Israelites annihilated entire ethnic groups or tribes:

the Israelites killed all Amalekites, including men, women, and children

(1 Samuel 15:1–20); the Israelites killed all men, women, and children in the battle of Jericho(Joshua 6:15–21), and the Israelites killed all men, women and children of several Canaanite tribes (Joshua 10:28–42). However, some scholars believe that these accounts in the Torah are exaggerated or metaphorical.

Arab-Israeli conflict

During the Palestine-Israeli conflict, people use the Torah (Tanakh) as a way to murder Palestinians, but the IDF has said "That we don't condone the killing of innocent Palestinians".

Palestinians as "Amalekites"

On several occasions, Palestinians have been associated with biblical antagonists, particularly with the Amalekites. For example, Rabbi Israel Hess has recommended that Palestinians be killed, based on biblical verses such as 1 Samuel 15.

Other religions

Buddhism

Hinduism

Neo-paganism

In the United States and Europe, neo-pagan beliefs have been associated with many terrorist incidents. Although the majority of neo-pagans oppose violence and racism, folkish factions of Odinism, Wotanism, and Ásatrú emphasize their Nordic cultural heritage and idolize warriors. For these reasons, a 1999 Federal Bureau of Investigation report on domestic terrorism which was titled Project Megiddo described Odinism as “[lending] itself to violence and [having] the potential to inspire its followers to violence.” As of 2017, the Southern Poverty Law Center has recognized at least two active neo-pagan hate groups in the United States. Many white supremacists

(especially those in prison) are converting to Odinism at increasing

rates, citing the impurity of Christianity and the failure of previous

groups to accomplish goals as the primary reasons for their conversion. Similarities between Odinism and other extremist groups such as Christian Identity facilitate conversions. The targets of neo-pagan violence are similar to those of white supremacist terrorists and nationalist terrorists, but an added target includes Christians and churches.

Sikhism

Notable incidents

Conflicts and wars

Some authors have stated that "religious" conflicts are not

exclusively based on religious beliefs but should instead be seen as

clashes of communities, identities, and interests that are

secular-religious or at least very secular.

Some have asserted that attacks are carried out by those with

very strong religious convictions such as terrorists in the context of a

global religious war. Robert Pape, a political scientist who specializes in suicide terrorism argues that much of the modern Muslim suicide terrorism is secularly based.

Although the causes of terrorism are complex, it may be safe to assume

that terrorists are partially reassured by their religious views that

their god is on their side and that it will reward them in Heaven for punishing unbelievers.

These conflicts are among the most difficult to resolve,

particularly when both sides believe that God is on their side and that

He has endorsed the moral righteousness of their claims. One of the most infamous quotes which is associated with religious fanaticism was uttered in 1209 during the siege of Béziers, a Crusader asked the Papal Legate Arnaud Amalric how to tell Catholics from Cathars when the city was taken, to which Amalric replied:

"Caedite eos. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius", or "Kill them all; God will recognize his."

Ritual violence

Ritual violence may be directed against victims (e.g., human and nonhuman animal sacrifice and ritual slaughter) or self-inflicted (religious self-flagellation).

According to the hunting hypothesis, created by Walter Burkert in Homo Necans, carnivorous behavior is considered a form of violence. Burkett suggests that the anthropological phenomenon of religion grew out of rituals that were connected with hunting and the associated feelings of guilt over the violence that hunting required.