From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

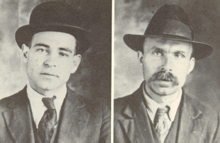

Anarchist trial defendants Bartolomeo Vanzetti (left) and Nicola Sacco (right)

Nicola Sacco (pronounced [niˈkɔːla ˈsakko]; April 22, 1891 – August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (pronounced [bartoloˈmɛːo vanˈtsetti, -ˈdzet-]; June 11, 1888 – August 23, 1927) were Italian immigrant anarchists

who were controversially accused of murdering Alessandro Berardelli and

Frederick Parmenter, a guard and paymaster, during the April 15, 1920, armed robbery of the Slater and Morrill Shoe Company in Braintree, Massachusetts, United States. Seven years later, they were executed in the electric chair at Charlestown State Prison.

After a few hours' deliberation on July 14, 1921, the jury convicted Sacco and Vanzetti of first-degree murder and they were sentenced to death by the trial judge. Anti-Italianism, anti-immigrant,

and anti-anarchist bias were suspected as having heavily influenced the

verdict. A series of appeals followed, funded largely by the private

Sacco and Vanzetti Defense Committee. The appeals were based on recanted

testimony, conflicting ballistics evidence, a prejudicial pretrial

statement by the jury foreman, and a confession by an alleged

participant in the robbery. All appeals were denied by trial judge Webster Thayer and also later denied by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.

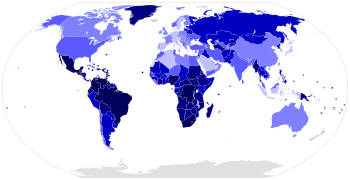

By 1926, the case had drawn worldwide attention. As details of the

trial and the men's suspected innocence became known, Sacco and Vanzetti

became the center of one of the largest causes célèbres in modern history. In 1927, protests on their behalf were held in every major city in North America and Europe, as well as in Tokyo, Sydney, Melbourne, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Dubai, Montevideo, Johannesburg, and Auckland.

Celebrated writers, artists, and academics pleaded for their

pardon or for a new trial. Harvard law professor and future Supreme

Court justice Felix Frankfurter argued for their innocence in a widely read Atlantic Monthly article that was later published in book form. Even the Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini was convinced of their innocence and attempted to pressure American authorities to have them released. The two were scheduled to die in April 1927, accelerating the outcry. Responding to a massive influx of telegrams urging their pardon, Massachusetts governor Alvan T. Fuller

appointed a three-man commission to investigate the case. After weeks

of secret deliberation that included interviews with the judge, lawyers,

and several witnesses, the commission upheld the verdict. Sacco and

Vanzetti were executed in the electric chair just after midnight on

August 23, 1927.

Investigations in the aftermath of the executions continued

throughout the 1930s and '40s. The publication of the men's letters,

containing eloquent professions of innocence, intensified belief in

their wrongful execution. Additional ballistics tests and incriminating

statements by the men's acquaintances have clouded the case. On August

23, 1977—the 50th anniversary of the executions—Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis

issued a proclamation that Sacco and Vanzetti had been unfairly tried

and convicted and that "any disgrace should be forever removed from

their names".

Background

Sacco was a shoemaker and a night watchman, born April 22, 1891, in Torremaggiore, Province of Foggia, Apulia region (in Italian: Puglia), Italy, who migrated to the United States at the age of seventeen.

Before immigrating, according to a letter he sent while imprisoned,

Sacco worked on his father's vineyard, often sleeping out in the field

at night to prevent animals from destroying the crops. Vanzetti was a fishmonger born June 11, 1888, in Villafalletto, Province of Cuneo, Piedmont region. Both left Italy for the US in 1908, although they did not meet until a 1917 strike.

The men were believed to be followers of Luigi Galleani, an Italian anarchist who advocated revolutionary violence, including bombing and assassination. Galleani published Cronaca Sovversiva (Subversive Chronicle), a periodical that advocated violent revolution, and a bomb-making manual called La Salute è in voi! (Health is in you!). At the time, Italian anarchists – in particular the Galleanist group – ranked at the top of the United States government's list of dangerous enemies.

Since 1914, the Galleanists had been identified as suspects in several

violent bombings and assassination attempts, including an attempted mass

poisoning. Publication of Cronaca Sovversiva was suppressed in July 1918, and the government deported Galleani and eight of his closest associates on June 24, 1919.

Other Galleanists remained active for three years, 60 of whom

waged an intermittent campaign of violence against US politicians,

judges, and other federal and local officials, especially those who had

supported deportation of alien radicals. Among the dozen or more violent

acts was the bombing of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer's home on June 2, 1919. In that incident, Carlo Valdinocci, a former editor of Cronaca Sovversiva,

related to Sacco and Vanzetti, was killed when the bomb intended for

Palmer exploded in the editor's hands. Radical pamphlets entitled "Plain

Words" signed "The Anarchist Fighters" were found at the scene of this

and several other midnight bombings that night.

Several Galleanist associates were suspected or interrogated

about their roles in the bombing incidents. Two days before Sacco and

Vanzetti were arrested, a Galleanist named Andrea Salsedo fell to his death from the US Justice Department's Bureau of Investigation (BOI) offices on the 14th floor of 15 Park Row in New York City. Salsedo had worked in the Canzani Printshop in Brooklyn, to where federal agents traced the "Plain Words" leaflet.

Roberto Elia, a fellow New York printer and admitted anarchist,

was later deposed in the inquiry, and testified that Salsedo had

committed suicide for fear of betraying the others. He portrayed himself

as the 'strong' one who had resisted the police. According to anarchist writer Carlo Tresca, Elia changed his story later, stating that Federal agents had thrown Salsedo out the window.

Robbery

.38 Harrington & Richardson top break revolver similar to pistol carried by Berardelli

.32 Colt Model 1903 automatic pistol

.32 Savage Model 1907 semi-automatic pistol

The Slater-Morrill Shoe Company factory was located on Pearl Street in Braintree, Massachusetts.

On April 15, 1920, two men were robbed and killed while transporting

the company's payroll in two large steel boxes to the main factory. One

of them, Alessandro Berardelli—a security guard—was shot four times as he reached for his hip-holstered .38-caliber, Harrington & Richardson

revolver; his gun was not recovered from the scene. The other man,

Frederick Parmenter—a paymaster who was unarmed—was shot twice: once in the chest and a second time, fatally, in the back as he attempted to flee. The robbers seized the payroll boxes and escaped in a stolen dark blue Buick that sped up and was carrying several other men.

As the car was being driven away by Michael Codispoti, the robbers fired wildly at company workers nearby.

A coroner's report and subsequent ballistic investigation revealed that

six bullets removed from the murdered men's bodies were of .32 automatic (ACP) caliber. Five of these .32-caliber bullets were all fired from a single semi-automatic pistol, a .32-caliber Savage Model 1907, which used a particularly narrow-grooved barrel rifling with a right-hand twist. Two of the bullets were recovered from Berardelli's body. Four .32 automatic brass shell casings were found at the murder scene, manufactured by one of three firms: Peters, Winchester, or Remington.

The Winchester cartridge case was of a relatively obsolete cartridge

loading, which had been discontinued from production some years earlier.

Two days after the robbery, police located the robbers' Buick; several

12-gauge shotgun shells were found on the ground nearby.

Arrests and indictment

An earlier attempted robbery of another shoe factory occurred on December 24, 1919, in Bridgewater,

Massachusetts, by people identified as Italian who used a car that was

seen escaping to Cochesett in West Bridgewater. Police speculated that

Italian anarchists perpetrated the robberies to finance their

activities. Bridgewater police chief Michael E. Stewart suspected that

known Italian anarchist Ferruccio Coacci was involved. Stewart

discovered that Mario Buda (aka 'Mike' Boda) lived with Coacci.

When Chief Stewart later arrived at the Coacci home, only Buda

was living there, and when questioned, he said that Coacci owned a .32

Savage automatic pistol, which he kept in the kitchen.

A search of the kitchen did not locate the gun, but Stewart found (in a

kitchen drawer) a manufacturer's technical diagram for a Model 1907 of

the exact type of .32 caliber pistol used to shoot Parmenter and

Berardelli. Stewart asked Buda if he owned a gun, and the man produced a .32-caliber Spanish-made automatic pistol. Buda told police that he owned a 1914 Overland automobile, which was being repaired.

The car was delivered for repairs four days after the Braintree crimes,

but it was old and apparently had not been run for five months.

Tire tracks were seen near the abandoned Buick getaway car, and Chief

Stewart surmised that two cars had been used in the getaway, and that

Buda's car might have been the second car.

When Stewart discovered that Coacci had worked for both shoe

factories that had been robbed, he returned with the Bridgewater police.

Mario Buda was not home,

but on May 5, 1920, he arrived at the garage with three other men,

later identified as Sacco, Vanzetti, and Riccardo Orciani. The four men

knew each other well; Buda would later refer to Sacco and Vanzetti as

"the best friends I had in America".

Sacco and Vanzetti boarded a streetcar, but were tracked down and

soon arrested. When searched by police, both denied owning any guns,

but were found to be holding loaded pistols. Sacco was found to have an

Italian passport, anarchist literature, a loaded .32 Colt Model 1903

automatic pistol, and twenty-three .32 Automatic cartridges in his

possession; several of those bullet cases were of the same obsolescent

type as the empty Winchester .32 casing found at the crime scene, and

others were manufactured by the firms of Peters and Remington, much like

other casings found at the scene. Vanzetti had four 12-gauge shotgun shells and a five-shot nickel-plated .38-caliber

Harrington & Richardson revolver similar to the .38 carried by

Berardelli, the slain Braintree guard, whose weapon was not found at the

scene of the crime. When they were questioned, the pair denied any connection to anarchists.

Orciani was arrested May 6, but gave the alibi that he had been

at work on the day of both crimes. Sacco had been at work on the day of

the Bridgewater crimes but said that he had the day off on April 15—the

day of the Braintree crimes— and was charged with those murders. The

self-employed Vanzetti had no such alibis and was charged for the

attempted robbery and attempted murder in Bridgewater and the robbery

and murder in the Braintree crimes. Sacco and Vanzetti were charged with the crime of murder on May 5, 1920, and indicted four months later on September 14.

Following Sacco and Vanzetti's indictment for murder for the Braintree robbery, Galleanists

and anarchists in the United States and abroad began a campaign of

violent retaliation. Two days later on September 16, 1920, Mario Buda

allegedly orchestrated the Wall Street bombing,

where a time-delay dynamite bomb packed with heavy iron sash-weights in

a horse-drawn cart exploded, killing 38 people and wounding 134. In 1921, a booby trap bomb mailed to the American ambassador in Paris exploded, wounding his valet. For the next six years, bombs exploded at other American embassies all over the world.

Trials

Bridgewater crimes trial

Rather

than accept court-appointed counsel, Vanzetti chose to be represented

by John P. Vahey, a former foundry superintendent and future state court

judge who had been practicing law since 1905, most notably with his

brother James H. Vahey and his law partner Charles Hiller Innes. James Graham, who was recommended by supporters, also served as defense counsel. Frederick G. Katzmann, the Norfolk and Plymouth County District Attorney, prosecuted the case. The presiding judge was Webster Thayer,

who was already assigned to the court before this case was scheduled. A

few weeks earlier he had given a speech to new American citizens

decrying Bolshevism and anarchism's threat to American institutions. He

supported the suppression of functionally violent radical speech, and

incitement to commit violent acts. He was known to dislike foreigners but was considered to be a fair judge.

The trial began on June 22, 1920. The prosecution presented

several witnesses who put Vanzetti at the scene of the crime. Their

descriptions varied, especially with respect to the shape and length of

Vanzetti's mustache.

Physical evidence included a shotgun shell retrieved at the scene of

the crime and several shells found on Vanzetti when he was arrested.

The defense produced 16 witnesses, all Italians from Plymouth,

who testified that at the time of the attempted robbery they had bought eels from Vanzetti for Eastertide,

in accordance with their traditions. Such details reinforced the

difference between the Italians and the jurors. Some testified in

imperfect English, others through an interpreter, whose inability to

speak the same dialect of Italian as the witnesses hampered his

effectiveness. On cross examination, the prosecution found it easy to

make the witnesses appear confused about dates. A boy who testified

admitted to rehearsing his testimony. "You learned it just like a piece

at school?" the prosecutor asked. "Sure", he replied.

The defense tried to rebut the eyewitnesses with testimony that

Vanzetti always wore his mustache in a distinctive long style, but the

prosecution rebutted this.

The defense case went badly and Vanzetti did not testify in his own defense. During the trial, he said that his lawyers had opposed putting him on the stand. That same year, defense attorney Vahey told the governor that Vanzetti had refused his advice to testify.

Decades later, a lawyer who assisted Vahey in the defense said that the

defense attorneys left the choice to Vanzetti, but warned him that it

would be difficult to prevent the prosecution from using cross

examination to challenge the credibility of his character based on his

political beliefs. He said that Vanzetti chose not to testify after

consulting with Sacco. Herbert B. Ehrmann, who later joined the defense team, wrote many years later that the dangers of putting Vanzetti on the stand were very real.

Another legal analysis of the case faulted the defense for not offering

more to the jury by letting Vanzetti testify, concluding that by his

remaining silent it "left the jury to decide between the eyewitnesses

and the alibi witness without his aid. In these circumstances a verdict

of not guilty would have been very unusual". That analysis claimed that

"no one could say that the case was closely tried or vigorously fought

for the defendant".

Vanzetti complained during his sentencing on April 9, 1927, for

the Braintree crimes, that Vahey "sold me for thirty golden money like

Judas sold Jesus Christ."

He accused Vahey of having conspired with the prosecutor "to agitate

still more the passion of the juror, the prejudice of the juror" towards

"people of our principles, against the foreigner, against slackers."

On July 1, 1920, the jury deliberated for five hours and returned

guilty verdicts on both counts, armed robbery and first-degree murder.

Before sentencing, Judge Thayer learned that during deliberations, the

jury had tampered with the shotgun shells found on Vanzetti at the time

of his arrest to determine if the shot they contained was of sufficient

size to kill a man. Since that prejudiced the jury's verdict on the murder charge, Thayer declared that part a mistrial.

On August 16, 1920, he sentenced Vanzetti on the charge of armed

robbery to a term of 12 to 15 years in prison, the maximum sentence

allowed. An assessment

of Thayer's conduct of the trial said "his stupid rulings as to the

admissibility of conversations are about equally divided" between the

two sides and thus provided no evidence of partiality.

Sacco and Vanzetti both denounced Thayer. Vanzetti wrote, "I will try to see Thayer death [sic]

before his pronunciation of our sentence" and asked fellow anarchists

for "revenge, revenge in our names and the names of our living and

dead."

In 1927, advocates for Sacco and Vanzetti charged that this case

was brought first because a conviction for the Bridgewater crimes would

help convict him for the Braintree crimes, where evidence against him

was weak. The prosecution countered that the timing was driven by the

schedules of different courts that handled the cases. The defense raised only minor objections in an appeal that was not accepted. A few years later, Vahey joined Katzmann's law firm.

Braintree crimes trial

Sacco and Vanzetti went on trial for their lives in Dedham, Massachusetts, May 21, 1921, at Dedham, Norfolk County, for the Braintree robbery and murders. Webster Thayer

again presided; he had asked to be assigned to the trial. Katzmann

again prosecuted for the State. Vanzetti was represented by brothers

Jeremiah and Thomas McAnraney. Sacco was represented by Fred H. Moore and William J. Callahan. The choice of Moore, a former attorney for the Industrial Workers of the World,

proved a key mistake for the defense. A notorious radical from

California, Moore quickly enraged Judge Thayer with his courtroom

demeanor, often doffing his jacket and once, his shoes. Reporters

covering the case were amazed to hear Judge Thayer, during a lunch

recess, proclaim, "I'll show them that no long-haired anarchist from

California can run this court!" and later, "You wait till I give my

charge to the jury. I'll show them." Throughout the trial, Moore and Thayer clashed repeatedly over procedure and decorum.

Authorities anticipated a possible bomb attack and had the Dedham

courtroom outfitted with heavy, sliding steel doors and cast-iron

shutters that were painted to appear wooden.

Each day during the trial, the courthouse was placed under heavy police

security, and Sacco and Vanzetti were escorted to and from the

courtroom by armed guards.

The Commonwealth relied on evidence that Sacco was absent from

his work in a shoe factory on the day of the murders; that the

defendants were in the neighborhood of the Braintree robbery-murder

scene on the morning when it occurred, being identified as having been

there seen separately and also together; that the Buick getaway car was

also in the neighborhood and that Vanzetti was near and in it; that

Sacco was seen near the scene of the murders before they occurred and

also was seen to shoot Berardelli after Berardelli fell and that that

shot caused his death; that used shell casings were left at the scene of

the murders, some of which could have been found to have been

discharged from a .32 pistol afterwards found on Sacco; that a cap was

found at the scene of the murders, which witnesses identified as

resembling one formerly worn by Sacco; and that both men were members of

anarchist cells that espoused violence, including assassination.

Among the more important witnesses called by the prosecution was

salesman Carlos E. Goodridge, who stated that as the getaway car raced

within twenty-five feet of him, one of the car's occupants, whom he

identified as being Sacco, pointed a gun in his direction.

Both defendants offered alibis that were backed by several

witnesses. Vanzetti testified that he had been selling fish at the time

of the Braintree robbery. Sacco testified that he had been in Boston applying for a passport at the Italian consulate. He stated he had lunched in Boston's North End with several friends, each of whom testified on his behalf. Prior to the trial, Sacco's lawyer, Fred Moore,

went to great lengths to contact the consulate employee whom Sacco said

he had talked with on the afternoon of the crime. Once contacted in

Italy, the clerk said he remembered Sacco because of the unusually large

passport photo he presented. The clerk also remembered the date, April

15, 1920, but he refused to return to the United States to testify (a

trip requiring two ship voyages), citing his ill health. Instead he

executed a sworn deposition that was read aloud in court and quickly

dismissed.

Much of the trial focused on material evidence, notably bullets, guns, and the cap. Prosecution witnesses testified that Bullet III,

the .32-caliber bullet that had fatally wounded Berardelli, was from a

discontinued Winchester .32 Auto cartridge loading so obsolete that the

only bullets similar to it that anyone could locate to make comparisons

were those found in the cartridges in Sacco's pockets.

Prosecutor Frederick Katzmann decided to participate in a forensic

bullet examination using bullets test-fired from Sacco's .32 Colt

Automatic after the defense arranged for such tests. Sacco, saying he

had nothing to hide, had allowed his gun to be test-fired, with experts

for both sides present, during the trial's second week. The prosecution

matched bullets fired through the gun to those taken from one of the

slain men.

In court, District Attorney Katzmann called two forensic gun expert witnesses, Capt. Charles Van Amburgh of Springfield Armory and Capt. William Proctor of the Massachusetts State Police, who testified that they believed that of the four bullets recovered from Berardelli's body, Bullet III

– the fatal bullet – exhibited rifling marks consistent with those

found on bullets fired from Sacco's .32 Colt Automatic pistol. In rebuttal, two defense forensic gun experts testified that Bullet III did not match any of the test bullets from Sacco's Colt.

After the trial, Capt. Proctor signed an affidavit stating that he

could not positively identify Sacco's .32 Colt as the only pistol that

could have fired Bullet III. This meant that Bullet III could have been fired from any of the 300,000 .32 Colt Automatic pistols then in circulation.

All witnesses to the shooting testified that they saw one gunman shoot

Berardelli four times, yet the defense never questioned how only one of

four bullets found in the deceased guard was identified as being fired

from Sacco's Colt.

Vanzetti was being tried under Massachusetts' felony-murder rule,

and the prosecution sought to implicate him in the Braintree robbery by

the testimony of several witnesses: one testified that he was in the

getaway car, and others who stated they saw Vanzetti in the vicinity of

the Braintree factory around the time of the robbery.

No direct evidence tied Vanzetti's .38 nickel-plated Harrington &

Richardson five-shot revolver to the crime scene, except for the fact

that it was identical in type and appearance to one owned by the slain

guard Berardelli, which was missing from the crime scene. All six bullets recovered from the victims were .32 caliber, fired from at least two different automatic pistols.

The prosecution claimed Vanzetti's .38 revolver had originally

belonged to the slain Berardelli, and that it had been taken from his

body during the robbery. No one testified to seeing anyone take the

gun, but Berardelli had an empty holster and no gun on him when he was

found.

Additionally, witnesses to the payroll shooting had described

Berardelli as reaching for his gun on his hip when he was cut down by

pistol fire from the robbers.

District Attorney Katzmann pointed out that Vanzetti had lied at

the time of his arrest, when making statements about the .38 revolver

found in his possession. He claimed that the revolver was his own, and

that he carried it for self-protection, yet he incorrectly described it

to police as a six-shot revolver instead of a five-shot.

Vanzetti also told police that he had purchased only one box of

cartridges for the gun, all of the same make, yet his revolver was

loaded with five .38 cartridges of varying brands.

At the time of his arrest, Vanzetti also claimed that he had bought

the gun at a store (but could not remember which one), and that it cost

$18 or $19 (three times its actual market value). He lied about where he had obtained the .38 cartridges found in the revolver.

The prosecution traced the history of Berardelli's .38 Harrington & Richardson (H&R) revolver. Berardelli's wife testified that she and her husband dropped off the gun for repair at the Iver Johnson Co. of Boston a few weeks before the murder.

According to the foreman of the Iver Johnson repair shop, Berardelli's

revolver was given a repair tag with the number of 94765, and this

number was recorded in the repair logbook with the statement "H. &

R. revolver, .38-calibre, new hammer, repairing, half an hour".

However, the shop books did not record the gun's serial number, and the

caliber was apparently incorrectly labeled as .32 instead of

.38-caliber.

The shop foreman testified that a new spring and hammer were put into

Berardelli's Harrington & Richardson revolver. The gun was claimed

and the half-hour repair paid for, though the date and identity of the

claimant were not recorded.

After examining Vanzetti's .38 revolver, the foreman testified that

Vanzetti's gun had a new replacement hammer in keeping with the repair

performed on Berardelli's revolver.

The foreman explained that the shop was always kept busy repairing 20

to 30 revolvers per day, which made it very hard to remember individual

guns or keep reliable records of when they were picked up by their

owners.

But, he said that unclaimed guns were sold by Iver Johnson at the end

of each year, and the shop had no record of an unclaimed gun sale of

Berardelli's revolver.

To reinforce the conclusion that Berardelli had reclaimed his revolver

from the repair shop, the prosecution called a witness who testified

that he had seen Berardelli in possession of a .38 nickel-plated

revolver the Saturday night before the Braintree robbery.

After hearing testimony from the repair shop employee that "the

repair shop had no record of Berardelli picking up the gun, the gun was

not in the shop nor had it been sold", the defense put Vanzetti on the

stand where he testified that "he had actually bought the gun several

months earlier from fellow anarchist Luigi Falzini for five dollars" –

in contradiction to what he had told police upon his arrest.

This was corroborated by Luigi Falzini (Falsini), a friend of

Vanzetti's and a fellow Galleanist, who stated that, after buying the

.38 revolver from one Riccardo Orciani, he sold it to Vanzetti. The defense also called two expert witnesses, a Mr. Burns and a Mr.

Fitzgerald, who each testified that no new spring and hammer had ever

been installed in the revolver found in Vanzetti's possession.

The District Attorney's final piece of material evidence was a

flop-eared cap claimed to have been Sacco's. Sacco tried the cap on in

court and, according to two newspaper sketch artists who ran cartoons

the next day, it was too small, sitting high on his head. But Katzmann

insisted the cap fitted Sacco and, noting a hole in the back where Sacco

had hung the cap on a nail each day, continued to refer to it as his,

and in denying later appeals, Judge Thayer often cited the cap as

material evidence. During the 1927 Lowell Commission investigation,

however, Braintree's Police Chief admitted that he had torn the cap open

upon finding it at the crime scene a full day after the murders.

Doubting the cap was Sacco's, the chief told the commission it could not

have lain in the street "for thirty hours with the State Police, the

local police, and two or three thousand people there."

Protest for Sacco and Vanzetti in

London, 1921

Controversy clouded the prosecution witnesses who identified Sacco as

having been at the scene of the crime. One, a bookkeeper named Mary

Splaine, precisely described Sacco as the man she saw firing from the

getaway car. From Felix Frankfurter's account from The Atlantic Monthly article:

Viewing the scene from a distance of from sixty to eighty

feet, she saw a man previously unknown to her in a car traveling at the

rate of from fifteen to eighteen miles per hour, and she saw him only

for a distance of about thirty feet—that is to say, for from one and a

half to three seconds.

Yet cross examination revealed that Splaine was unable to identify

Sacco at the inquest but had recall of great details of Sacco's

appearance over a year later. While a few others singled out Sacco or

Vanzetti as the men they had seen at the scene of the crime, far more

witnesses, both prosecution and defense, could not identify them.

The defendants' radical politics may have played a role in the

verdict. Judge Thayer, though a sworn enemy of anarchists, warned the

defense against bringing anarchism into the trial. Yet defense attorney

Fred Moore felt he had to call both Sacco and Vanzetti as witnesses to

let them explain why they were fully armed when arrested. Both men

testified that they had been rounding up radical literature when

apprehended, and that they had feared another government deportation

raid. Yet both hurt their case with rambling discourses on radical

politics that the prosecution mocked. The prosecution also brought out

that both men had fled the draft by going to Mexico in 1917.

On July 21, 1921, the jury deliberated for three hours, broke for

dinner, and then returned the guilty verdicts. Supporters later

insisted that Sacco and Vanzetti had been convicted for their anarchist

views, yet every juror insisted that anarchism had played no part in

their decision to convict the two men. At that time, a first-degree

murder conviction in Massachusetts was punishable by death. Sacco and

Vanzetti were bound for the electric chair unless the defense could find

new evidence.

The verdicts and the likelihood of death sentences immediately

roused international opinion. Demonstrations were held in 60 Italian

cities and a flood of mail was sent to the American embassy in Paris.

Demonstrations followed in a number of Latin American cities. Anatole France, veteran of the campaign for Alfred Dreyfus and recipient of the 1921 Nobel Prize for Literature,

wrote an "Appeal to the American People": "The death of Sacco and

Vanzetti will make martyrs of them and cover you with shame. You are a

great people. You ought to be a just people."

Defense committee

In

1921, most of the nation had not yet heard of Sacco and Vanzetti. Brief

mention of the conviction appeared on page three of the New York Times.

Defense attorney Moore radicalized and politicized the process by

discussing Sacco and Vanzetti's anarchist beliefs, attempting to suggest

that they were prosecuted primarily for their political beliefs and the

trial was part of a government plan to stop the anarchist movement in

the United States. His efforts helped stir up support but were so costly

that he was eventually dismissed from the defense team.

The Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee was formed on May 9, 1920,

immediately following the arrests, by a group of fellow anarchists,

headed by Vanzetti's 23-year-old friend Aldino Felicani. Over the next

seven years, it raised $300,000. Defense attorney Fred Moore drew on its funds for his investigations.

Differences arose when Moore tried to determine who had committed the

Braintree crimes over objections from anarchists that he was doing the

government's work. After the Committee hired William G. Thompson to

manage the legal defense, he objected to its propaganda efforts.

A Defense Committee publicist wrote an article about the first trial that was published in The New Republic.

In the winter of 1920–1921, the Defense Committee sent stories to labor

union publications every week. It produced pamphlets with titles like Fangs at Labor's Throat, sometimes printing thousands of copies. It sent speakers to Italian communities in factory towns and mining camps.

The Committee eventually added staff from outside the anarchist

movement, notably Mary Donovan, who had experience as a labor leader and

Sinn Féin organizer. In 1927, she and Felicani together recruited Gardner Jackson, a Boston Globe

reporter from a wealthy family, to manage publicity and serve as a

mediator between the Committee's anarchists and the growing number of

supporters with more liberal political views, who included socialites,

lawyers, and intellectuals.

Jackson bridged the gap between the radicals and the social elite

so well that Sacco thanked him a few weeks before his execution:

We are one heart, but unfortunately we represent two

different class. ... But, whenever the heart of one of the upper class

join with the exploited workers for the struggle of the right in the

human feeling is the feel of an spontaneous attraction and brotherly

love to one another.

The noted American author John Dos Passos joined the committee and wrote its 127-page official review of the case: Facing the Chair: Story of Americanization of Two Foreignborn Workmen.

Dos Passos concluded it "barely possible" that Sacco might have

committed murder as part of a class war, but that the soft-hearted

Vanzetti was clearly innocent. "Nobody in his right mind who was

planning such a crime would take a man like that along," Dos Passos

wrote of Vanzetti. After the executions, the Committee continued its work, helping to gather material that eventually appeared as The Letters of Sacco and Vanzetti.

Motions for a new trial

Multiple separate motions for a new trial were denied by Judge Thayer.

One motion, the so-called Hamilton-Proctor motion, involved the

forensic ballistic evidence presented by the expert witnesses for the

prosecution and defense. The prosecution's firearms expert, Charles Van

Amburgh, had re-examined the evidence in preparation for the motion. By

1923, bullet-comparison technology had improved somewhat, and Van

Amburgh submitted photos of the bullets fired from Sacco's .32 Colt in

support of the argument that they matched the bullet that killed

Berardelli. In response, the controversial self-proclaimed "firearms expert" for the defense, Albert H. Hamilton,

conducted an in-court demonstration involving two brand new Colt

.32-caliber automatic pistols belonging to Hamilton, along with Sacco's

.32 Colt of the same make and caliber. In front of Judge Thayer and the

lawyers for both sides, Hamilton disassembled all three pistols and

placed the major component parts – barrel, barrel bushing, recoil

spring, frame, slide, and magazine – into three piles on the table

before him.

He explained the functions of each part and began to demonstrate how

each was interchangeable, in the process intermingling the parts of all

three pistols. Judge Thayer stopped Hamilton and demanded that he reassemble Sacco's pistol with its proper parts.

Other motions focused on the jury foreman and a prosecution

ballistics expert. In 1923, the defense filed an affidavit from a friend

of the jury foreman, who swore that prior to the trial, the jury

foreman had allegedly said of Sacco and Vanzetti, "Damn them, they ought

to hang them anyway!" That same year, the defense read to the court an

affidavit by Captain William Proctor (who had died shortly after

conclusion of the trial) in which Proctor stated that he could not say

that Bullet III was fired by Sacco's .32 Colt pistol. At the conclusion of the appeal hearings, Thayer denied all motions for a new trial on October 1, 1924.

Several months later, in February 1924, Judge Thayer asked one of

the firearms experts for the prosecution, Capt. Charles Van Amburgh, to

reinspect Sacco's Colt and determine its condition. With District

Attorney Katzmann present, Van Amburgh took the gun from the clerk and

started to take it apart. Van Amburgh quickly noticed that the barrel to Sacco's gun was brand new, being still covered in the manufacturer's protective rust preventative.

Judge Thayer began private hearings to determine who had tampered with

the evidence by switching the barrel on Sacco's gun. During three weeks

of hearings, Albert Hamilton and Captain Van Amburgh squared off,

challenging each other's authority. Testimony suggested that Sacco's

gun had been treated with little care, and frequently disassembled for

inspection. New defense attorney William Thompson insisted that no one

on his side could have switched the barrels "unless they wanted to run

their necks into a noose."

Albert Hamilton swore he had only taken the gun apart while being

watched by Judge Thayer. Judge Thayer made no finding as to who had

switched the .32 Colt barrels, but ordered the rusty barrel returned to

Sacco's Colt.

After the hearing concluded, unannounced to Judge Thayer, Captain Van

Amburgh took both Sacco's and Vanzetti's guns, along with the bullets

and shells involved in the crime to his home where he kept them until a Boston Globe

exposé revealed the misappropriation in 1960. Meanwhile, Van Amburgh

bolstered his own credentials by writing an article on the case for True

Detective Mysteries. The 1935 article charged that prior to the

discovery of the gun barrel switch, Albert Hamilton had tried to walk

out of the courtroom with Sacco's gun but was stopped by Judge Thayer.

Although several historians of the case, including Francis Russell, have

reported this story as factual, nowhere in transcripts of the private

hearing on the gun barrel switch was this incident ever mentioned. The

same year the True Detective article was published, a study of

ballistics in the case concluded, "what might have been almost

indubitable evidence was in fact rendered more than useless by the

bungling of the experts."

Appeal to the Supreme Judicial Court

The defense appealed Thayer's denial of their motions to the Supreme Judicial Court

(SJC), the highest level of the state's judicial system. Both sides

presented arguments to its five judges on January 11–13, 1926. The SJC returned a unanimous ruling on May 12, 1926, upholding Judge Thayer's decisions.

The Court did not have the authority to review the trial record as a

whole or to judge the fairness of the case. Instead, the judges

considered only whether Thayer had abused his discretion in the course

of the trial. Thayer later claimed that the SJC had "approved" the

verdicts, which advocates for the defendants protested as a

misinterpretation of the Court's ruling, which only found "no error" in

his individual rulings.

Medeiros confession

In

November 1925, Celestino Medeiros, an ex-convict awaiting trial for

murder, confessed to committing the Braintree crimes. He absolved Sacco

and Vanzetti of participation.

In May, once the SJC had denied their appeal and Medeiros was

convicted, the defense investigated the details of Medeiros' story.

Police interviews led them to the Morelli gang based in Providence,

Rhode Island. They developed an alternative theory of the crime based on

the gang's history of shoe-factory robberies, connections to a car like

that used in Braintree, and other details. Gang leader Joe Morelli bore

a striking resemblance to Sacco.

The defense filed a motion for a new trial based on the Medeiros confession on May 26, 1926. In support of their motion they included 64 affidavits. The prosecution countered with 26 affidavits. When Thayer heard arguments from September 13 to 17, 1926,

the defense, along with their Medeiros-Morelli theory of the crime,

charged that the U.S. Justice Department was aiding the prosecution by

withholding information obtained in its own investigation of the case.

Attorney William Thompson made an explicitly political attack: "A

government which has come to value its own secrets more than it does the

lives of its citizens has become a tyranny, whether you call it a

republic, a monarchy, or anything else!"

Judge Thayer denied this motion for a new trial on October 23, 1926.

After arguing against the credibility of Medeiros, he addressed the

defense claims against the federal government, saying the defense was

suffering from "a new type of disease, ... a belief in the existence of

something which in fact and truth has no such existence."

Three days later, the Boston Herald responded to Thayer's decision by reversing its longstanding position and calling for a new trial. Its editorial, "We Submit", earned its author a Pulitzer Prize. No other newspapers followed suit.

Second appeal to the Supreme Judicial Court

The defense promptly appealed again to the Supreme Judicial Court and presented their arguments on January 27 and 28, 1927. While the appeal was under consideration, Harvard law professor and future Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter published an article in the Atlantic Monthly

arguing for a retrial. He noted that the SJC had already taken a very

narrow view of its authority when considering the first appeal, and

called upon the court to review the entire record of the case. He called

their attention to Thayer's lengthy statement that accompanied his

denial of the Medeiros appeal, describing it as "a farrago of

misquotations, misrepresentations, suppressions, and mutilations,"

"honeycombed with demonstrable errors."

At the same time, Major Calvin Goddard

was a ballistics expert who had helped pioneer the use of the

comparison microscope in forensic ballistic research. He offered to

conduct an independent examination of the gun and bullet forensic

evidence by using techniques that he had developed for use with the

comparison microscope.

Goddard first offered to conduct a new forensic examination for the

defense, which rejected it, and then to the prosecution, which accepted

his offer. Using the comparison microscope, Goddard compared Bullet III

and a .32 Auto shell casing found at the Braintree shooting with that

of several .32 Auto test cartridges fired from Sacco's .32 Colt

automatic pistol. Goddard concluded that not only did Bullet III

match the rifling marks found on the barrel of Sacco's .32 Colt pistol,

but that scratches made by the firing pin of Sacco's .32 Colt on the

primers of spent shell casings test-fired from Sacco's Colt matched

those found on the primer of a spent shell casing recovered at the

Braintree murder scene. More sophisticated comparative examinations in 1935, 1961, and 1983

each reconfirmed the opinion that the bullet the prosecution said killed

Berardelli and one of the cartridge cases introduced into evidence were

fired in Sacco's .32 Colt automatic. However, in his book on new evidence in the Sacco and Vanzetti case, historian David E. Kaiser

wrote that Bullet III and its shell casing, as presented, had been

substituted by the prosecution and were not genuinely from the scene.

The Supreme Judicial Court denied the Medeiros appeal on April 5, 1927. Summarizing the decision, The New York Times

said that the SJC had determined that "the judge had a right to rule as

he did" but that the SJC "did not deny the validity of the new

evidence."

The SJC also said: "It is not imperative that a new trial be granted

even though evidence is newly discovered and, if presented to a jury,

would justify a different verdict."

Protests and advocacy

In

1924, referring to his denial of motions for a new trial, Judge Thayer

confronted a Massachusetts lawyer: "Did you see what I did with those

anarchistic bastards the other day?" the judge said. "I guess that will

hold them for a while! Let them go and see now what they can get out of

the Supreme Court!" The outburst remained a secret until 1927 when its

release fueled the arguments of Sacco and Vanzetti's defenders. The New York World

attacked Thayer as "an agitated little man looking for publicity and

utterly impervious to the ethical standards one has the right to expect

of a man presiding in a capital case."

Many socialists and intellectuals campaigned for a retrial without success. John Dos Passos came to Boston to cover the case as a journalist, stayed to author a pamphlet called Facing the Chair, and was arrested in a demonstration on August 10, 1927, along with writer Dorothy Parker, trade union organizer and Socialist Party leader Powers Hapgood and activist Catharine Sargent Huntington. After being arrested while picketing the State House, the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay

pleaded her case to the governor in person and then wrote an appeal: "I

cry to you with a million voices: answer our doubt ... There is need in

Massachusetts of a great man tonight."

Others who wrote to Fuller or signed petitions included Albert Einstein, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells. The president of the American Federation of Labor

cited "the long period of time intervening between the commission of

the crime and the final decision of the Court" as well as "the mental

and physical anguish which Sacco and Vanzetti must have undergone during

the past seven years" in a telegram to the governor.

Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, the target of two anarchist assassination attempts,

quietly made inquiries through diplomatic channels and was prepared to

ask Governor Fuller to commute the sentences if it appeared his request

would be granted.

In 1926, a bomb presumed to be the work of anarchists destroyed

the house of Samuel Johnson, the brother of Simon Johnson and garage

owner that called police the night of Sacco and Vanzetti's arrest.

In August 1927, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) called for a three-day nationwide walkout to protest the pending executions. The most notable response came in the Walsenburg coal district of Colorado, where 1,132 out of 1,167 miners participated in the walkout. It led to the Colorado coal strike of 1927.

Defendants in prison

For their part, Sacco and Vanzetti seemed to alternate between moods

of defiance, vengeance, resignation, and despair. The June 1926 issue of

Protesta Umana, published by their Defense Committee, carried an

article signed by Sacco and Vanzetti that appealed for retaliation by

their colleagues. In the article, Vanzetti wrote, "I will try to see

Thayer death [sic]

before his pronunciation of our sentence," and asked fellow anarchists

for "revenge, revenge in our names and the names of our living and

dead." The article made a reference to La Salute è in voi!, the title of Galleani's bomb-making manual.

The Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee newspaper relays a message from Sacco and Vanzetti: "La Salute è in voi!"

Both wrote dozens of letters asserting their innocence, insisting

they had been framed because they were anarchists. Their conduct in

prison consistently impressed guards and wardens. In 1927, the Dedham

jail chaplain wrote to the head of an investigatory commission that he

had seen no evidence of guilt or remorse on Sacco's part. Vanzetti

impressed fellow prisoners at Charlestown State Prison as a bookish intellectual, incapable of committing any violent crime. Novelist John Dos Passos,

who visited both men in jail, observed of Vanzetti, "nobody in his

right mind who was planning such a crime would take a man like that

along." Vanzetti developed his command of English to such a degree that journalist Murray Kempton

later described him as "the greatest writer of English in our century

to learn his craft, do his work, and die all in the space of seven

years."

While Sacco was in the Norfolk County Jail,

his seven-year-old son, Dante, would sometimes stand on the sidewalk

outside the jail and play catch with his father by throwing a ball over

the wall.

Sentencing

On April 9, 1927, Judge Thayer heard final statements from Sacco and Vanzetti. In a lengthy speech Vanzetti said:

I would not wish to a dog or to a snake, to the most low

and misfortunate creature of the earth, I would not wish to any of them

what I have had to suffer for things that I am not guilty of. But my

conviction is that I have suffered for things that I am guilty of. I am

suffering because I am a radical and indeed I am a radical; I have

suffered because I am an Italian and indeed I am an Italian ... if you

could execute me two times, and if I could be reborn two other times, I

would live again to do what I have done already.

Thayer declared that the responsibility for the conviction rested

solely with the jury's determination of guilt. "The Court has absolutely

nothing to do with that question." He sentenced each of them to "suffer

the punishment of death by the passage of a current of electricity

through your body" during the week beginning July 10. He twice postponed the execution date while the governor considered requests for clemency.

On May 10, a package bomb addressed to Governor Fuller was intercepted in the Boston post office.

Clemency appeal and the Governor's Advisory Committee

In response to public protests that greeted the sentencing, Massachusetts Governor Alvan T. Fuller

faced last-minute appeals to grant clemency to Sacco and Vanzetti. On

June 1, 1927, he appointed an Advisory Committee of three: President Abbott Lawrence Lowell of Harvard, President Samuel Wesley Stratton of MIT, and Probate Judge Robert Grant.

They were presented with the task of reviewing the trial to determine

whether it had been fair. Lowell's appointment was generally well

received, for though he had controversy in his past, he had also at

times demonstrated an independent streak. The defense attorneys

considered resigning when they determined that the Committee was biased

against the defendants, but some of the defendants' most prominent

supporters, including Harvard Law Professor Felix Frankfurter and Judge Julian W. Mack of the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, persuaded them to stay because Lowell "was not entirely hopeless."

One of the defense attorneys, though ultimately very critical of

the Committee's work, thought the Committee members were not really

capable of the task the Governor set for them:

No member of the Committee had the essential

sophistication that comes with experience in the trial of criminal

cases. ... The high positions in the community held by the members of

the Committee obscured the fact that they were not really qualified to

perform the difficult task assigned to them.

He also thought that the Committee, particularly Lowell, imagined it

could use its fresh and more powerful analytical abilities to outperform

the efforts of those who had worked on the case for years, even finding

evidence of guilt that professional prosecutors had discarded.

Grant was another establishment figure, a probate court judge from 1893 to 1923 and an Overseer of Harvard University from 1896 to 1921, and the author of a dozen popular novels.

Some criticized Grant's appointment to the Committee, with one defense

lawyer saying he "had a black-tie class concept of life around him," but

Harold Laski

in a conversation at the time found him "moderate." Others cited

evidence of xenophobia in some of his novels, references to "riff-raff"

and a variety of racial slurs. His biographer allows that he was "not a

good choice," not a legal scholar, and handicapped by age. Stratton, the

one member who was not a "Boston Brahmin," maintained the lowest public profile of the three and hardly spoke during its hearings.

In their earlier appeals, the defense was limited to the trial

record. The Governor's Committee, however, was not a judicial

proceeding, so Judge Thayer's comments outside the courtroom could be

used to demonstrate his bias. Once Thayer told reporters that "No

long-haired anarchist from California can run this court!"

According to the affidavits of eyewitnesses, Thayer also lectured

members of his clubs, calling Sacco and Vanzetti "Bolsheviki!" and

saying he would "get them good and proper". During the Dedham trial's

first week, Thayer said to reporters: "Did you ever see a case in which

so many leaflets and circulars have been spread ... saying people

couldn't get a fair trial in Massachusetts? You wait till I give my

charge to the jury, I'll show them!" In 1924, Thayer confronted a Massachusetts lawyer at Dartmouth, his alma mater,

and said: "Did you see what I did with those anarchistic bastards the

other day. I guess that will hold them for a while. ... Let them go to

the Supreme Court now and see what they can get out of them." The Committee knew that, following the verdict, Boston Globe

reporter Frank Sibley, who had covered the trial, wrote a protest to

the Massachusetts attorney general condemning Thayer's blatant bias.

Thayer's behavior both inside the courtroom and outside of it had become

a public issue, with the New York World

attacking Thayer as "an agitated little man looking for publicity and

utterly impervious to the ethical standards one has the right to expect

of a man presiding in a capital case."

On July 12–13, 1927, following testimony by the defense firearms

expert Albert H. Hamilton before the Committee, the Assistant District

Attorney for Massachusetts, Dudley P. Ranney, took the opportunity to

cross-examine Hamilton. He submitted affidavits questioning Hamilton's

credentials as well as his performance during the New York trial of

Charles Stielow, in which Hamilton's testimony linking rifling marks to a

bullet used to kill the victim nearly sent an innocent man to the

electric chair.

The Committee also heard from Braintree's police chief who told them

he had found the cap on Pearl Street, allegedly dropped by Sacco during

the crime, a full 24-hours after the getaway car had fled the scene.

The chief doubted the cap belonged to Sacco and called the whole trial a

contest "to see who could tell the biggest lies."

After two weeks of hearing witnesses and reviewing evidence, the

Committee determined that the trial had been fair and a new trial was

not warranted. They assessed the charges against Thayer as well. Their

criticism, using words provided by Judge Grant,

was direct: "He ought not to have talked about the case off the bench,

and doing so was a grave breach of judicial decorum." But they also

found some of the charges about his statements unbelievable or

exaggerated, and they determined that anything he might have said had no

impact on the trial. The panel's reading of the trial transcript

convinced them that Thayer "tried to be scrupulously fair." The

Committee also reported that the trial jurors were almost unanimous in

praising Thayer's conduct of the trial.

A defense attorney later noted ruefully that the release of the

Committee's report "abruptly stilled the burgeoning doubts among the

leaders of opinion in New England."

Supporters of the convicted men denounced the Committee. Harold Laski

told Holmes that the Committee's work showed that Lowell's "loyalty to

his class ... transcended his ideas of logic and justice."

The Sacco e Vanzetti monument in

Carrara.

Defense attorneys William G. Thompson and Herbert B. Ehrmann stepped down from the case in August 1927 and were replaced by Arthur D. Hill.

Execution and funeral

The

executions were scheduled for midnight between August 22 and 23, 1927.

On August 15, a bomb exploded at the home of one of the Dedham jurors. On Sunday, August 21, more than 20,000 protesters assembled on Boston Common.

Sacco and Vanzetti awaited execution in their cells at Charlestown State Prison, and both men refused a priest several times on their last day, as they were atheists.

Their attorney William Thompson asked Vanzetti to make a statement

opposing violent retaliation for his death and they discussed forgiving

one's enemies.

Thompson also asked Vanzetti to swear to his and Sacco's innocence one

last time, and Vanzetti did. Celestino Medeiros, whose execution had

been delayed in case his testimony was required at another trial of

Sacco and Vanzetti, was executed first. Sacco was next and walked

quietly to the electric chair, then shouted "Farewell, mother."

Vanzetti, in his final moments, shook hands with guards and thanked

them for their kind treatment, read a statement proclaiming his

innocence, and finally said, "I wish to forgive some people for what

they are now doing to me." Following the executions, death masks were made of the men.

Violent demonstrations swept through many cities the next day,

including Geneva, London, Paris, Amsterdam, and Tokyo. In South America

wildcat strikes closed factories. Three died in Germany, and protesters

in Johannesburg burned an American flag outside the American embassy. It has been alleged that some of these activities were organized by the Communist Party.

At Langone Funeral Home in Boston's North End,

more than 10,000 mourners viewed Sacco and Vanzetti in open caskets

over two days. At the funeral parlor, a wreath over the caskets

announced In attesa l'ora della vendetta (Awaiting the hour of

vengeance). On Sunday, August 28, a two-hour funeral procession bearing

huge floral tributes moved through the city. Thousands of marchers took

part in the procession, and over 200,000 came out to watch. Police blocked the route, which passed the State House, and at one point mourners and the police clashed. The hearses reached Forest Hills Cemetery where, after a brief eulogy, the bodies were cremated. The Boston Globe called it "one of the most tremendous funerals of modern times."

Will H. Hays, head of the motion picture industry's umbrella organization, ordered all film of the funeral procession destroyed.

Sacco's ashes were sent to Torremaggiore,

the town of his birth, where they are interred at the base of a

monument erected in 1998. Vanzetti's ashes were buried with his mother

in Villafalletto.

Continuing protests and analyses

Italian anarchist Severino Di Giovanni,

one of the most vocal supporters of Sacco and Vanzetti in Argentina,

bombed the American embassy in Buenos Aires a few hours after the two

men were sentenced to death.

A few days after the executions, Sacco's widow thanked Di Giovanni by

letter for his support and added that the director of the tobacco firm Combinados had offered to produce a cigarette brand named "Sacco & Vanzetti". On November 26, 1927, Di Giovanni and others bombed a Combinados tobacco shop. On December 24, 1927, Di Giovanni blew up the headquarters of The National City Bank of New York and of the Bank of Boston in Buenos Aires in apparent protest of the execution. In December 1928, Di Giovanni and others failed in an attempt to bomb the train in which President-elect Herbert Hoover was traveling during his visit to Argentina.

Three months later, bombs exploded in the New York City Subway,

in a Philadelphia church, and at the home of the mayor of Baltimore.

The house of one of the jurors in the Dedham trial was bombed, throwing

him and his family from their beds. On May 18, 1928, a bomb destroyed

the front porch of the home of executioner Robert Elliott. As late as 1932, Judge Thayer's home was wrecked and his wife and housekeeper were injured in a bomb blast. Afterward, Thayer lived permanently at his club in Boston, guarded 24 hours a day until his death on April 18, 1933.

In October 1927, H. G. Wells wrote an essay that discussed the case at length. He called it "a case like the Dreyfus case,

by which the soul of a people is tested and displayed." He felt that

Americans failed to understand what about the case roused European

opinion:

The guilt or innocence of these two Italians is not the

issue that has excited the opinion of the world. Possibly they were

actual murderers, and still more possibly they knew more than they would

admit about the crime. ... Europe is not "retrying" Sacco and Vanzetti

or anything of the sort. It is saying what it thinks of Judge Thayer.

Executing political opponents as political opponents after the fashion

of Mussolini and Moscow

we can understand, or bandits as bandits; but this business of trying

and executing murderers as Reds, or Reds as murderers, seems to be a new

and very frightening line for the courts of a State in the most

powerful and civilized Union on earth to pursue.

He used the case to complain that Americans were too sensitive to

foreign criticism: "One can scarcely let a sentence that is not highly

flattering glance across the Atlantic without some American blowing up."

In 1928, Upton Sinclair published his novel Boston,

an indictment of the American judicial system. He explored Vanzetti's

life and writings, as its focus, and mixed fictional characters with

historical participants in the trials. Though his portrait of Vanzetti

was entirely sympathetic, Sinclair disappointed advocates for the

defense by failing to absolve Sacco and Vanzetti of the crimes, however

much he argued that their trial had been unjust.

Years later, he explained: "Some of the things I told displeased the

fanatical believers; but having portrayed the aristocrats as they were, I

had to do the same thing for the anarchists."

While doing research for the book, Sinclair was told confidentially by

Sacco and Vanzetti's former lawyer Fred H. Moore that the two were

guilty and that he (Moore) had supplied them with fake alibis; Sinclair

was inclined to believe that that was, indeed, the case, and later

referred to this as an "ethical problem", but he did not include the

information about the conversation with Moore in his book.

When the letters Sacco and Vanzetti wrote appeared in print in 1928, journalist Walter Lippmann

commented: "If Sacco and Vanzetti were professional bandits, then

historians and biographers who attempt to deduce character from personal

documents might as well shut up shop. By every test that I know of for

judging character, these are the letters of innocent men." On January 3, 1929, as Gov. Fuller left the inauguration of his successor, he found a copy of the Letters thrust at him by someone in the crowd. He knocked it to the ground "with an exclamation of contempt."

Intellectual and literary supporters of Sacco and Vanzetti continued to speak out. In 1936, on the day when Harvard

celebrated its 300th anniversary, 28 Harvard alumni issued a statement

attacking the University's retired President Lowell for his role on the

Governor's Advisory Committee in 1927. They included Heywood Broun, Malcolm Cowley, Granville Hicks, and John Dos Passos.

Massachusetts judicial reform

Following

the SJC's assertion that it could not order a new trial even if there

was new evidence that "would justify a different verdict," a movement

for "drastic reform" quickly took shape in Boston's legal community.

In December 1927, four months after the executions, the Massachusetts

Judicial Council cited the Sacco and Vanzetti case as evidence of

"serious defects in our methods of administering justice." It proposed a

series of changes designed to appeal to both sides of the political

divide, including restrictions on the number and timing of appeals. Its

principal proposal addressed the SJC's right to review. It argued that a

judge would benefit from a full review of a trial, and that no one man

should bear the burden in a capital case. A review could defend a judge

whose decisions were challenged and make it less likely that a governor

would be drawn into a case. It asked for the SJC to have right to order a

new trial "upon any ground if the interests of justice appear to

inquire it." Governor Fuller endorsed the proposal in his January 1928 annual message.

The Judicial Council repeated its recommendations in 1937 and

1938. Finally, in 1939, the language it had proposed was adopted. Since

that time, the SJC has been required to review all death penalty cases,

to consider the entire case record, and to affirm or overturn the

verdict on the law and on the evidence or "for any other reason that

justice may require" (Mass. General Laws, 1939 ch. 341)

Historical viewpoints

Many

historians, especially legal historians, have concluded the Sacco and

Vanzetti prosecution, trial, and aftermath constituted a blatant

disregard for political civil liberties, and especially criticize Thayer's decision to deny a retrial.

John W. Johnson has said that the authorities and jurors were influenced by strong anti-Italian prejudice and the prejudice against immigrants widely held at the time, especially in New England.

Against charges of racism and racial prejudice, Paul Avrich and Brenda

and James Lutz point out that both men were known anarchist members of a

militant organization, members of which had been conducting a violent

campaign of bombing and attempted assassinations, acts condemned by most

Americans of all backgrounds.

Though in general anarchist groups did not finance their militant

activities through bank robberies, a fact noted by the investigators of

the Bureau of Investigation, this was not true of the Galleanist group.

Mario Buda readily told an interviewer: "Andavamo a prenderli dove c'erano" ("We used to go and get it [money] where it was") – meaning factories and banks. The guard Berardelli was also Italian.

Johnson and Avrich suggest that the government prosecuted Sacco

and Vanzetti for the robbery-murders as a convenient means to put a stop

to their militant activities as Galleanists, whose bombing campaign at

the time posed a lethal threat, both to the government and to many

Americans.

Faced with a secretive underground group whose members resisted

interrogation and believed in their cause, Federal and local officials

using conventional law enforcement tactics had been repeatedly stymied

in their efforts to identify all members of the group or to collect

enough evidence for a prosecution.

Most historians believe that Sacco and Vanzetti were involved at

some level in the Galleanist bombing campaign, although their precise

roles have not been determined. In 1955, Charles Poggi, a longtime anarchist and American citizen, traveled to Savignano in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy to visit old comrades, including the Galleanists' principal bombmaker, Mario "Mike" Buda. While discussing the Braintree robbery, Buda told Poggi, "Sacco c'era" (Sacco was there). Poggi added that he "had a strong feeling that Buda himself was one of the robbers, though I didn't ask him and he didn't say."

Whether Buda and Ferruccio Coacci, whose shared rental house contained

the manufacturer's diagram of a .32 Savage automatic pistol (matching

the .32 Savage pistol believed to have been used to shoot both

Berardelli and Parmenter), had also participated in the Braintree

robbery and murders would remain a matter of speculation.

Later evidence and investigations

In 1941, anarchist leader Carlo Tresca, a member of the Sacco and Vanzetti Defense Committee, told Max Eastman, "Sacco was guilty but Vanzetti was innocent",

although it is clear from his statement that Tresca equated guilt only

with the act of pulling the trigger, i.e., Vanzetti was not the

principal triggerman in Tresca's view, but was an accomplice to Sacco.

This conception of innocence is in sharp contrast to the legal one. Both The Nation and The New Republic

refused to publish Tresca's revelation, which Eastman said occurred

after he pressed Tresca for the truth about the two men's involvement in

the shooting. The story finally appeared in National Review in October 1961. Others who had known Tresca confirmed that he had made similar statements to them,

but Tresca's daughter insisted her father never hinted at Sacco's

guilt. Others attributed Tresca's revelations to his disagreements with

the Galleanists.

Labor organizer Anthony Ramuglia, an anarchist in the 1920s, said

in 1952 that a Boston anarchist group had asked him to be a false alibi

witness for Sacco. After agreeing, he had remembered that he had been

in jail on the day in question, so he could not testify.

Both Sacco and Vanzetti had previously fled to Mexico, changing

their names in order to evade draft registration, a fact the prosecutor

in their murder trial used to demonstrate their lack of patriotism and

which they were not allowed to rebut. Sacco and Vanzetti's supporters

would later argue that the men fled the country to avoid persecution and

conscription; their critics said they left to escape detection and

arrest for militant and seditious activities in the United States.

However, a 1953 Italian history of anarchism written by anonymous

colleagues revealed a different motivation:

Several dozen Italian anarchists left the United States

for Mexico. Some have suggested they did so because of cowardice.

Nothing could be more false. The idea to go to Mexico arose in the minds

of several comrades who were alarmed by the idea that, remaining in the

United States, they would be forcibly restrained from leaving for

Europe, where the revolution that had burst out in Russia that February

promised to spread all over the continent.

In October 1961, ballistic tests were run with improved technology on Sacco's Colt semi-automatic pistol. The results confirmed that the bullet that killed Berardelli in 1920 was fired from Sacco's pistol.

The Thayer court's habit of mistakenly referring to Sacco's .32 Colt

pistol as well as any other automatic pistol as a "revolver" (a common

custom of the day) has sometimes mystified later-generation researchers

attempting to follow the forensic evidence trail.

In 1987, Charlie Whipple, a former Boston Globe

editorial page editor, revealed a conversation that he had with

Sergeant Edward J. Seibolt in 1937. According to Whipple, Seibolt said

that "we switched the murder weapon in that case", but indicated that he

would deny this if Whipple ever printed it. However, at the time of the Sacco and Vanzetti trial, Seibolt was only a

patrolman, and did not work in the Boston Police ballistics department;

Seibolt died in 1961 without corroborating Whipple's story. In 1935, Captain Charles Van Amburgh, a key ballistics witness for the prosecution, wrote a six-part article on the case for a pulp detective magazine.

Van Amburgh described a scene in which Thayer caught defense ballistics

expert Hamilton trying to leave the courtroom with Sacco's gun.

However, Thayer said nothing about such a move during the hearing on the

gun barrel switch and refused to blame either side. Following the

private hearing on the gun barrel switch, Van Amburgh kept Sacco's gun

in his house, where it remained until the Boston Globe did an exposé in 1960.

In 1973, a former mobster published a confession by Frank "Butsy"

Morelli, Joe's brother. "We whacked them out, we killed those guys in

the robbery," Butsy Morelli told Vincent Teresa. "These two greaseballs Sacco and Vanzetti took it on the chin."

Before his death in June 1982, Giovanni Gambera, a member of the

four-person team of anarchist leaders who met shortly after the arrest

of Sacco and Vanzetti to plan their defense, told his son that "everyone

[in the anarchist inner circle] knew that Sacco was guilty and that

Vanzetti was innocent as far as the actual participation in killing."

Months before he died, the distinguished jurist Charles E. Wyzanski, Jr.,

who had presided for 45 years on the U.S. District Court in

Massachusetts, wrote to Russell stating, "I myself am persuaded by your

writings that Sacco was guilty." The judge's assessment was significant,

because he was one of Felix Frankfurter's "Hot Dogs", and Justice Frankfurter had advocated his appointment to the federal bench.

The Los Angeles Times

published an article on December 24, 2005, "Sinclair Letter Turns Out

to Be Another Exposé", which references a newly discovered letter from

Upton Sinclair to attorney John Beardsley in which Sinclair, a socialist

writer famous for his muckraking novels, revealed a conversation with

Fred Moore, attorney for Sacco and Vanzetti. In that conversation, in

response to Sinclair's request for the truth, Moore stated that both

Sacco and Vanzetti were in fact guilty, and that Moore had fabricated

their alibis in an attempt to avoid a guilty verdict. The Los Angeles Times

interprets subsequent letters as indicating that, to avoid loss of

sales to his radical readership, particularly abroad, and due to fears

for his own safety, Sinclair didn't change the premise of his novel in

that respect.

However, Sinclair also expressed in those letters doubts as to whether

Moore deserved to be trusted in the first place, and he did not actually

assert the innocence of the two in the novel, focusing instead on the

argument that the trial they got was not fair.

Dukakis proclamation

In 1977, as the 50th anniversary of the executions approached, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis

asked the Office of the Governor's Legal Counsel to report on "whether

there are substantial grounds for believing–at least in the light of the

legal standards of today–that Sacco and Vanzetti were unfairly

convicted and executed" and to recommend appropriate action.

The resulting "Report to the Governor in the Matter of Sacco and

Vanzetti" detailed grounds for doubting that the trial was conducted

fairly in the first instance, and argued as well that such doubts were

only reinforced by "later-discovered or later-disclosed evidence."

The report questioned prejudicial cross-examination that the trial

judge allowed, the judge's hostility, the fragmentary nature of the

evidence, and eyewitness testimony that came to light after the trial.

It found the judge's charge to the jury troubling for the way it

emphasized the defendants' behavior at the time of their arrest and

highlighted certain physical evidence that was later called into

question.

The report also dismissed the argument that the trial had been subject

to judicial review, noting that "the system for reviewing murder cases

at the time ... failed to provide the safeguards now present."

Based on recommendations of the Office of Legal Counsel, Dukakis

declared August 23, 1977, the 50th anniversary of their execution, as

Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti Memorial Day.

His proclamation, issued in English and Italian, stated that Sacco and

Vanzetti had been unfairly tried and convicted and that "any disgrace

should be forever removed from their names." He did not pardon them,

because that would imply they were guilty. Neither did he assert their

innocence. A resolution to censure Dukakis failed in the Massachusetts Senate by a vote of 23 to 12. Dukakis later expressed regret only for not reaching out to the families of the victims of the crime.

Later tributes