From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance.

This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against

one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on

its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and

foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state. A person who

commits treason is known in law as a traitor.

Historically, in common law

countries, treason also covered the murder of specific social

superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife or that of a

master by his servant. Treason (i.e. disloyalty) against one's monarch

was known as high treason and treason against a lesser superior was petty treason.

As jurisdictions around the world abolished petty treason, "treason"

came to refer to what was historically known as high treason.

At times, the term traitor has been used as a political epithet, regardless of any verifiable treasonable action. In a civil war or insurrection, the winners may deem the losers to be traitors. Likewise the term traitor

is used in heated political discussion – typically as a slur against

political dissidents, or against officials in power who are perceived as

failing to act in the best interest of their constituents. In certain

cases, as with the Dolchstoßlegende (Stab-in-the-back myth), the accusation of treason towards a large group of people can be a unifying political message.

History

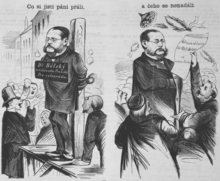

Cartoon depicting Václav Bělský (1818–1878),

Mayor of Prague from 1863 until 1867, in charge of the city during

Prussian

occupation in July 1866. Some forces wanted to try him for high treason

(left: "What some men wished" – "Dr. Bělský for high treason"), but he

got a full confidence from the Council of Prague (right: "but what they

did not expect" – "address of confidence from the city of Prague").

In English law, high treason was punishable by being hanged, drawn and quartered (men) or burnt at the stake (women), although beheading

could be substituted by royal command (usually for royalty and

nobility). Those penalties were abolished in 1814, 1790 and 1973

respectively. The penalty was used by later monarchs against people who

could reasonably be called traitors. Many of them would now just be

considered dissidents.

Christian theology and political thinking until after the Enlightenment considered treason and blasphemy synonymous, as it challenged both the state and the will of God. Kings were considered chosen by God, and to betray one's country was to do the work of Satan.

The words "treason" and "traitor" are derived from the Latin tradere, "to deliver or hand over". Specifically, it is derived from the term "traditors", which refers to bishops and other Christians who turned over sacred scriptures or betrayed their fellow Christians to the Roman authorities under threat of persecution during the Diocletianic Persecution between AD 303 and 305.

Originally, the crime of treason was conceived of as being committed against the monarch; a subject failing in his duty of loyalty to the Sovereign and acting against the Sovereign was deemed to be a traitor. Queens Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard were executed for treason for adultery against Henry VIII,

although most historians regard the evidence against Anne Boleyn and

her alleged lovers to be dubious. As asserted in the 18th century trial

of Johann Friedrich Struensee in Denmark,

a man having sexual relations with a queen can be considered guilty not

only of ordinary adultery but also of treason against her husband, the

king.

The English Revolution in the 17th century and the French Revolution

in the 18th century introduced a radically different concept of loyalty

and treason, under which Sovereignty resides with "The Nation" or "The

People" - to whom also the Monarch has a duty of loyalty, and for

failing which the Monarch, too, could be accused of treason. Charles I in England and Louis XVI in France were found guilty of such treason and duly executed. However, when Charles II

was restored to his throne, he considered the revolutionaries who

sentenced his father to death as having been traitors in the more

traditional sense.

In medieval times, most treason cases were in the context of a

kingdom's internal politics. Though helping a foreign monarch against

one's own sovereign would also count as treason, such were only a

minority among treason cases. Conversely, in modern times, "traitor" and

"treason" are mainly used with reference to a person helping an enemy

in time of war or conflict.

During the American Revolution, a slave named Billy was sentenced to death on charges of treason to Virginia for having joined the British in their war against the American colonists - but was eventually pardoned by Thomas Jefferson, then Governor of Virginia.

Jefferson accepted the argument, put forward by Billy's well-wishers,

that - not being a citizen and not enjoying any of the benefits of being

one - Billy owed no loyalty to Virginia and therefore had committed no

treason. This was a ground-breaking case, since in earlier similar cases slaves were found guilty of treason and executed.

Under very different circumstances, a similar defense was put forward in the case of William Joyce, nicknamed Lord Haw-Haw, who had broadcast Nazi propaganda to the UK from Germany during the Second World War.

Joyce's defence team, appointed by the court, argued that, as an

American citizen and naturalised German, Joyce could not be convicted of

treason against the British Crown. However, the prosecution

successfully argued that, since he had lied about his nationality to

obtain a British passport and voted in Britain, Joyce did owe allegiance

to the king. Thus, Joyce was convicted of treason, and was eventually hanged.

After Napoleon fell from power for the first time, Marshal Michel Ney swore allegiance to the restored King Louis XVIII, but when the Emperor escaped from Elba, Ney resumed his Napoleonic allegiance, and commanded the French troops at the Battle of Waterloo.

After Napoleon was defeated, dethroned, and exiled for the second time

in the summer of 1815, Ney was arrested and tried for treason by the Chamber of Peers. In order to save Ney's life, his lawyer André Dupin argued that as Ney's hometown of Sarrelouis had been annexed by Prussia according to the Treaty of Paris of 1815, Ney was now a Prussian,

no longer owing allegiance to the King of France and therefore not

liable for treason in a French court. Ney ruined his lawyer's effort by

interrupting him and stating: "Je suis Français et je resterai Français!" (I am French and I will remain French!). Having refused that defence, Ney was duly found guilty of treason and executed.

Until the late 19th Century, Britain - like various other

countries - held to a doctrine of "perpetual allegiance to the

sovereign", dating back to feudal times, under which British subjects,

owing loyalty to the British Monarch, remained such even if they

emigrated to another country and took its citizenship. This became a

hotly debated issue in the aftermath of the 1867 Fenian Rising, when Irish-Americans who had gone to Ireland

to participate in the uprising and were caught were charged with

treason, as the British authorities considered them to be British

subjects. This outraged many Irish-Americans, to which the British

responded by pointing out that, just like British law, American law also

recognized perpetual allegiance. As a result, Congress passed the Expatriation Act of 1868,

which granted Americans the right to freely renounce their U.S.

citizenship. Britain followed suit with a similar law, and years later,

signed a treaty agreeing to treat British subjects who had become U.S.

citizens as no longer holding British nationality - and thus no longer

liable to a charge of treason.

Many nations' laws mention various types of treason. "Crimes

Related to Insurrection" is the internal treason, and may include a coup d'état.

"Crimes Related to Foreign Aggression" is the treason of cooperating

with foreign aggression positively regardless of the national inside and

outside. "Crimes Related to Inducement of Foreign Aggression" is the

crime of communicating with aliens secretly to cause foreign aggression or menace. Depending on the country, conspiracy is added to these.

In individual jurisdictions

Australia

In Australia, there are federal and state laws against treason, specifically in the states of New South Wales, South Australia and Victoria. Similarly to Treason laws in the United States, citizens of Australia owe allegiance to their sovereign at the federal and state level.

The federal law defining treason in Australia is provided under

section 80.1 of the Criminal Code, contained in the schedule of the

Commonwealth Criminal Code Act 1995. It defines treason as follows:

A person commits an offence, called treason, if the person:

- (a) causes the death of the Sovereign, the heir apparent of

the Sovereign, the consort of the Sovereign, the Governor-General or the

Prime Minister; or

- (b) causes harm to the Sovereign, the Governor-General or the Prime

Minister resulting in the death of the Sovereign, the Governor-General

or the Prime Minister; or

- (c) causes harm to the Sovereign, the Governor-General or the Prime

Minister, or imprisons or restrains the Sovereign, the Governor-General

or the Prime Minister; or

- (d) levies war, or does any act preparatory to levying war, against the Commonwealth; or

- (e) engages in conduct that assists by any means whatever, with intent to assist, an enemy:

- (i) at war with the Commonwealth, whether or not the existence of a state of war has been declared; and

- (ii) specified by Proclamation made for the purpose of this paragraph to be an enemy at war with the Commonwealth; or

- (f) engages in conduct that assists by any means whatever, with intent to assist:

- (i) another country; or

- (ii) an organisation;

- that is engaged in armed hostilities against the Australian Defence Force; or

- (g) instigates a person who is not an Australian citizen to make an

armed invasion of the Commonwealth or a Territory of the Commonwealth;

or

- (h) forms an intention to do any act referred to in a preceding paragraph and manifests that intention by an overt act.

A person is not guilty of treason under paragraphs (e), (f) or (h) if

their assistance or intended assistance is purely humanitarian in

nature.

The maximum penalty for treason is life imprisonment. Section 80.1AC of the Act creates the related offence of treachery.

New South Wales

The Treason Act 1351, the Treason Act 1795 and the Treason Act 1817 form part of the law of New South Wales. The Treason Act 1795 and the Treason Act 1817 have been repealed by Section 11 of the Crimes Act 1900,

except in so far as they relate to the compassing, imagining,

inventing, devising, or intending death or destruction, or any bodily

harm tending to death or destruction, maim, or wounding, imprisonment,

or restraint of the person of the heirs and successors of King George III of the United Kingdom,

and the expressing, uttering, or declaring of such compassings,

imaginations, inventions, devices, or intentions, or any of them.

Section 12 of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) creates an offence which is derived from section 3 of the Treason Felony Act 1848:

12 Compassing etc deposition of the

Sovereign—overawing Parliament etc

Whosoever, within New South Wales or without, compasses, imagines,

invents, devises, or intends to deprive or depose Our Most Gracious Lady

the Queen, her heirs or successors, from the style, honour, or Royal

name of the Imperial Crown of the United Kingdom, or of any other of Her

Majesty's dominions and countries, or to levy war against Her Majesty,

her heirs or successors, within any part of the United Kingdom, or any

other of Her Majesty's dominions, in order, by force or constraint, to

compel her or them to change her or their measures or counsels, or in

order to put any force or constraint upon, or in order to intimidate or

overawe, both Houses or either House of the Parliament of the United

Kingdom, or the Parliament of New South Wales, or to move or stir any

foreigner or stranger with force to invade the United Kingdom, or any

other of Her Majesty's dominions, or countries under the obeisance of

Her Majesty, her heirs or successors, and expresses, utters, or declares

such compassings, imaginations, inventions, devices, or intentions, or

any of them, by publishing any printing or writing, or by open and

advised speaking, or by any overt act or deed, shall be liable to

imprisonment for 25 years.

Section 16 provides that nothing in Part 2 repeals or affects anything enacted by the Treason Act 1351 (25 Edw.3 c. 2). This section reproduces section 6 of the Treason Felony Act 1848.

Victoria

The offence of treason was created by section 9A(1) of the Crimes Act 1958. It is punishable by a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.

South Australia

In

South Australia, treason is defined under Section 7 of the South

Australia Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 and punished under Section

10A. Any person convicted of treason against South Australia will

receive a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment.

Brazil

According to Brazilian law, treason is the crime of disloyalty by a citizen to the Federal Republic of Brazil,

applying to combatants of the Brazilian military forces. Treason during

wartime is the only crime for which a person can be sentenced to death (see capital punishment in Brazil).

The only military person in the history of Brazil to be convicted of treason was Carlos Lamarca, an army captain who deserted to become the leader of a communist-terrorist guerrilla against the military government.

Canada

Section 46 of the Criminal Code has two degrees of treason, called "high treason" and "treason." However, both of these belong to the historical category of high treason, as opposed to petty treason which does not exist in Canadian law. Section 46 reads as follows:

High treason

(1) Every one commits high treason who, in Canada,

- (a) kills or attempts to kill His Majesty, or does him any

bodily harm tending to death or destruction, maims or wounds him, or

imprisons or restrains him;

- (b) levies war against Canada or does any act preparatory thereto; or

- (c) assists an enemy at war with Canada, or any armed forces against

whom Canadian Forces are engaged in hostilities, whether or not a state

of war exists between Canada and the country whose forces they are.

Treason

(2) Every one commits treason who, in Canada,

- (a) uses force or violence for the purpose of overthrowing the government of Canada or a province;

- (b) without lawful authority, communicates or makes available to an

agent of a state other than Canada, military or scientific information

or any sketch, plan, model, article, note or document of a military or

scientific character that he knows or ought to know may be used by that

state for a purpose prejudicial to the safety or defence of Canada;

- (c) conspires with any person to commit high treason or to do anything mentioned in paragraph (a);

- (d) forms an intention to do anything that is high treason or that

is mentioned in paragraph (a) and manifests that intention by an overt act; or

- (e) conspires with any person to do anything mentioned in paragraph

(b) or forms an intention to do anything mentioned in paragraph (b) and

manifests that intention by an overt act.

It is also illegal for a Canadian citizen or a person who owes

allegiance to Her Majesty in right of Canada to do any of the above

outside Canada.

The penalty for high treason is life imprisonment.

The penalty for treason is imprisonment up to a maximum of life, or up

to 14 years for conduct under subsection (2)(b) or (e) in peacetime.

Finland

Finnish law distinguishes between two types of treasonable offences: maanpetos, treachery in war, and valtiopetos, an attack against the constitutional order. The terms maanpetos and valtiopetos

are unofficially translated as treason and high treason, respectively.

Both are punishable by imprisonment, and if aggravated, by life

imprisonment.

Maanpetos (translates literally to betrayal of land) consists in joining enemy armed forces, making war against Finland, or serving or collaborating with the enemy. Maanpetos

proper can only be committed under conditions of war or the threat of

war. Espionage, disclosure of a national secret, and certain other

related offences are separately defined under the same rubric in the

Finnish criminal code.

Valtiopetos (translates literally to betrayal of state)

consists in using violence or the threat of violence, or

unconstitutional means, to bring about the overthrow of the Finnish

constitution or to overthrow the president, cabinet or parliament or to

prevent them from performing their functions.

France

Article 411-1 of the French Penal Code defines treason as follows:

The acts defined by articles 411-2 to 411–11 constitute

treason where they are committed by a French national or a soldier in

the service of France, and constitute espionage where they are committed

by any other person.

Article 411-2 prohibits "handing over troops belonging to the French armed forces,

or all or part of the national territory, to a foreign power, to a

foreign organisation or to an organisation under foreign control, or to

their agents". It is punishable by life imprisonment and a fine of €750,000. Generally parole is not available until 18 years of a life sentence have elapsed.

Articles 411–3 to 411–10 define various other crimes of

collaboration with the enemy, sabotage, and the like. These are

punishable with imprisonment for between seven and 30 years. Article

411-11 make it a crime to incite any of the above crimes.

Besides treason and espionage, there are many other crimes

dealing with national security, insurrection, terrorism and so on. These

are all to be found in Book IV of the code.

Germany

German law differentiates between two types of treason: "High treason" (Hochverrat) and "treason" (Landesverrat). High treason, as defined in Section 81 of the German criminal code is defined as an attempt against the existence or the constitutional order of the Federal Republic of Germany

that is carried out either with the use of violence or the threat of

violence. It carries a penalty of life imprisonment or a fixed term of

at least ten years. In less serious cases, the penalty is 1–10 years in

prison. German criminal law also criminalises high treason against a German state. Preparation of either types of the crime is criminal and carries a penalty of up to five years.

The other type of treason, Landesverrat is defined in Section 94.

It is roughly equivalent to espionage; more precisely, it consists of

betraying a secret either directly to a foreign power, or to anyone not

allowed to know of it; in the latter case, treason is only committed if

the aim of the crime was explicitly to damage the Federal Republic or to

favor a foreign power. The crime carries a penalty of one to fifteen

years in prison. However, in especially severe cases, life imprisonment

or any term of at least five years may be sentenced.

As for many crimes with substantial threats of punishment active

repentance is to be considered in mitigation under §83a StGB (Section

83a, Criminal Code).

Notable cases involving Landesverrat are the Weltbühne trial during the Weimar Republic and the Spiegel scandal of 1962. On 30. July 2015, Germany's Public Prosecutor General Harald Range initiated criminal investigation proceedings against the German blog netzpolitik.org.

Hong Kong

Section 2 of the Crime Ordinance provides that levying war against the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

of the People's Republic of China, conspiring to do so, instigating a

foreigner to invade Hong Kong, or assisting any public enemy at war with

the HKSAR Government, is treason, punishable with life imprisonment.

Ireland

Article 39 of the Constitution of Ireland (adopted in 1937) states:

treason shall consist only in levying war against the

State, or assisting any State or person or inciting or conspiring with

any person to levy war against the State, or attempting by force of arms

or other violent means to overthrow the organs of government

established by the Constitution, or taking part or being concerned in or

inciting or conspiring with any person to make or to take part or be

concerned in any such attempt.

Following the enactment of the 1937 constitution, the Treason Act 1939 provided for imposition of the death penalty for treason. The Criminal Justice Act 1990 abolished the death penalty, setting the punishment for treason at life imprisonment, with parole in not less than forty years. No person has been charged under the Treason Act. Irish republican legitimatists who refuse to recognise the legitimacy of the Republic of Ireland have been charged with lesser crimes under the Offences against the State Acts 1939–1998.

Italy

The Italian law defines various types of crimes that could be generally described as treason (tradimento), although they are so many and so precisely defined that no one of them is simply called tradimento in the text of Codice Penale (Italian Criminal Code). The treason-type crimes are grouped as "crimes against the personhood of the State" (Crimini contro la personalità dello Stato) in the Second Book, First Title, of the Criminal Code.

Articles 241 to 274 detail crimes against the "international personhood of the State" such as "attempt against wholeness, independence and unity of the State" (art.241), "hostilities against a foreign State bringing the Italian State in danger of war" (art.244), "bribery of a citizen by a foreigner against the national interests" (art.246), and "political or military espionage" (art.257).

Articles 276 to 292 detail crimes against the "domestic personhood of the State", ranging from "attempt on the President of the Republic" (art.271), "attempt with purposes of terrorism or of subversion" (art.280), "attempt against the Constitution" (art.283), "armed insurrection against the power of the State" (art.284), and "civil war" (art.286).

Further articles detail other crimes, especially those of conspiracy, such as "political conspiracy through association" (art.305), or "armed association: creating and participating" (art.306).

The penalties for treason-type crimes before the abolition of the monarchy in 1948 included death as maximum penalty and, for some crimes, as the only penalty possible. Nowadays the maximum penalty is life imprisonment (ergastolo).

Japan

From 1947 Japan does not technically have a law of treason. Instead it has an offence against taking part in foreign aggression against the Japanese state (gaikan zai;

literally "crime of foreign mischief"). The law applies equally to

Japanese and non-Japanese people, while treason in other countries

usually applies only to their own citizens. Technically there are two

laws, one for the crime of inviting foreign mischief (Japan Criminal Code

section 2 clause 81) and the other for supporting foreign mischief once

a foreign force has invaded Japan. "Mischief" can be anything from

invasion to espionage. Before World War II, Imperial Japan had a crime similar to the English crime of high treason (Taigyaku zai), which applied to anyone who harmed the Japanese emperor or imperial family. This law was abolished by the American occupation force after World War II.

The application of "Crimes Related to Insurrection" to the Aum Shinrikyo cult of religious terrorists

was proposed from lawyers of a defendant who was a high-ranked

subordinate so that the cult leader solely would be deemed as

responsible. The court rejected this argument.

New Zealand

New Zealand has treason laws that are stipulated under the Crimes Act 1961. Section 73 of the Crimes Act reads as follows:

Every one owing allegiance to Her Majesty the Queen in right of New Zealand commits treason who, within or outside New Zealand,—

- (a) Kills or wounds or does grievous bodily harm to Her Majesty the Queen, or imprisons or restrains her; or

- (b) Levies war against New Zealand; or

- (c) Assists an enemy at war with New Zealand, or any armed forces

against which New Zealand forces are engaged in hostilities, whether or

not a state of war exists between New Zealand and any other country; or

- (d) Incites or assists any person with force to invade New Zealand; or

- (e) Uses force for the purpose of overthrowing the New Zealand Government; or

- (f) Conspires with any person to do anything mentioned in this section.

The penalty is life imprisonment, except for conspiracy, for which the maximum sentence is 14 years' imprisonment. Treason was the last capital crime in New Zealand law: the death penalty for the offence was not revoked until 1989, 28 years after it was abolished for murder.

Very few people have been prosecuted for the act of treason in New Zealand, and none have been prosecuted in recent years.

Norway

Article 85 of the Constitution of Norway states that "[a]ny person who obeys an order the purpose of which is to disturb the liberty and security of the Storting [Parliament] is thereby guilty of treason against the country."

Russia

Article 275 of the Criminal Code of Russia

defines treason as "espionage, disclosure of state secrets, or any

other assistance rendered to a foreign State, a foreign organization, or

their representatives in hostile activities to the detriment of the

external security of the Russian Federation,

committed by a citizen of the Russian Federation." The sentence is

imprisonment for 12 to 20 years. It is not a capital offence, even

though murder and some aggravated forms of attempted murder are

(although Russia currently has a moratorium on the death penalty).

Subsequent sections provide for further offences against state

security, such as armed rebellion and forcible seizure of power.

South Korea

According to Article 87 of the Criminal Code of South Korea,

"a person who creates a violence for the purpose of usurping the

national territory or subverting the Constitution" can be found guilty

of insurrection. The punishments for insurrection are as follows:

- "Ring Leader": death, imprisonment for life or imprisonment without prison labor for life.

- "A person who participates in a plot, or commands, or engages in

other essential activities": death, imprisonment for life, imprisonment

or imprisonment without prison labor, for not less than five years.

- "A person who has committed acts of killing, wounding, destroying or

plundering": death, imprisonment for life, imprisonment or imprisonment

without prison labor, for not less than five years.

- "A person who merely responds to the agitation and follows the lead

of another or merely joins in the violence": imprisonment or

imprisonment without prison labor for not more than five years.

Sweden

Sweden's treason laws are divided into three parts; Högförräderi (High treason), Landsförräderi (Treason) and Landssvek (Treachery).

High treason means crimes committed with the intent to put the

Nation, or parts thereof, under foreign rule or influence. It is

governed by Brottsbalken (Criminal Code) chapter 19 paragraph 1.

A person who, with intent that the country or a part of it will, by

violent or otherwise illegal means or with foreign assistance, be

subjugated by a foreign power or made dependent on such a power, or

that, in this way, a part of the country will be detached, undertakes an

action that involves danger of this intent being realised is guilty of

high treason and is sentenced to imprisonment for a fixed term of at

least ten and at most eighteen years, or for life or, if the danger was

minor, to imprisonment for at least four and at most ten years.

A person who, with intent that a measure or decision of the Head of

State, the Government, the Riksdag or the supreme courts will be forced

or impeded with foreign assistance, undertakes an action that involves

danger of this is also guilty of high treason.

Treason is only applicable when the nation is at war and involves

crimes committed with the intent of hindering, misguiding or betraying

the defence of the Nation. It is governed by Brottsbalken chapter 22

paragraph 1.

A person who, when the country is at war:

1. impedes, misleads or betrays others who are engaged in the

country’s defence, or induces them to mutiny, disloyalty or dejection;

2. betrays, destroys or damages property of importance for the total defence;

3. obtains personnel, property or services for the enemy; or

4. commits another similar treacherous act,

is, if the act is liable to result in considerable detriment to the

total defence, or includes considerable assistance to the enemy, guilty

of treason and is sentenced to imprisonment for a fixed term of at least

four and at most ten years, or for life.

Treachery is a lesser form of Treason, where the intended effects are

less severe. It is governed by Brottsbalken chapter 22 paragraph 2.

A person who commits an act referred to in Section 1 that is only liable

to result in detriment to the total defence to a lesser extent, or

includes more minor assistance to the enemy than is stated there, is

guilty of treachery and is sentenced to imprisonment for at most six

years.

Until 1973 Sweden also had another form of treason called Krigsförräderi (treason at war), which were acts of Treason committed by military personnel. Although Sweden had outlawed capital punishment in peace time in 1922, this type of treason carried the death penalty until 1973.

Some media reported that four teenagers (their names were not reported) were convicted of treason after they assaulted King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden by throwing a cake on his face on 6 September 2001. In reality they were however not convicted of treason but of Högmålsbrott, translated as Treasonable offence

in English, which in Swedish criminal law are acts with the intent to

overthrow the Form of Government, or impede or hinder the Government,

the Riksdag, the Supreme Court or the Head of State. The law also

prohibits the use of force against the King or any member of the Royal

Family. It is governed by Brottsbalken chapter 18. They were fined

between 80 and 100 days' income.

Switzerland

There is no single crime of treason in Swiss law; instead, multiple criminal prohibitions apply. Article 265 of the Swiss Criminal Code prohibits "high treason" (Hochverrat/haute trahison) as follows:

Whoever commits an act with the objective of violently

– changing the constitution of the Confederation or of a canton,

– removing the constitutional authorities of the state from office or making them unable to exercise their authority,

– separating Swiss territory from the Confederation or territory from a canton,

shall be punished with imprisonment of no less than a year.

A separate crime is defined in article 267 as "diplomatic treason" (Diplomatischer Landesverrat/Trahison diplomatique):

1. Whoever makes known or accessible a secret, the preservation of

which is required in the interest of the Confederation, to a foreign

state or its agents, (...) shall be punished with imprisonment of no

less than a year.

2. Whoever makes known or accessible a secret, the preservation of which

is required in the interest of the Confederation, to the public, shall

be punished with imprisonment of up to five years or a monetary penalty.

In 1950, in the context of the Cold War, the following prohibition of "foreign enterprises against the security of Switzerland" was introduced as article 266bis:

1 Whoever, with the purpose of inciting or supporting

foreign enterprises aimed against the security of Switzerland, enters

into contact with a foreign state or with foreign parties or other

foreign organizations or their agents, or makes or disseminates untrue

or tendentious claims (unwahre oder entstellende Behauptungen / informations inexactes ou tendancieuses), shall be punished with imprisonment of up to five years or a monetary penalty.

2 In grave cases the judge may pronounce a sentence of imprisonment of no less than a year.

The criminal code also prohibits, among other acts, the suppression

or falsification of legal documents or evidence relevant to the

international relations of Switzerland (art. 267, imprisonment of no

less than a year) and attacks against the independence of Switzerland

and incitement of a war against Switzerland (art. 266, up to life

imprisonment).

The Swiss military criminal code contains additional prohibitions

under the general title of "treason", which also apply to civilians, or

which in times of war civilians are also (or may by executive decision

be made) subject to. These include espionage or transmission of secrets to a foreign power (art. 86); sabotage (art. 86a); "military treason", i.e., the disruption of activities of military significance (art. 87); acting as a franc-tireur

(art. 88); disruption of military action by disseminating untrue

information (art. 89); military service against Switzerland by Swiss

nationals (art. 90); or giving aid to the enemy (art. 91). The penalties

for these crimes vary, but include life imprisonment in some cases.

Turkey

Treason per se

is not defined in the Turkish Penal Code. However, the law defines

crimes which are traditionally included in the scope of treason, such as

cooperating with the enemy during wartime. Treason is punishable by

imprisonment up to life.

Ukraine

Article 111, paragraph 1, of the Ukrainian Criminal Code (adopted in 2001) states:

High treason, that is an act

willfully committed by a citizen of Ukraine in the detriment of

sovereignty, territorial integrity and inviolability, defense

capability, and state, economic or information security of Ukraine:

joining the enemy at the time of martial law or armed conflict,

espionage, assistance in subversive activities against Ukraine provided

to a foreign state, a foreign organization or their representatives,-

shall be punishable by imprisonment for a term of ten to fifteen years.

Articles 109 to 114 set out other offences against the state, such as sabotage.

United Kingdom

The British law of treason is entirely statutory and has been so since the Treason Act 1351 (25 Edw. 3 St. 5 c. 2). The Act is written in Norman French, but is more commonly cited in its English translation.

The Treason Act 1351 has since been amended several times, and

currently provides for four categories of treasonable offences, namely:

- "when a man doth compass or imagine the death of our lord the

King, or of our lady his Queen or of their eldest son and heir"

(following the Succession to the Crown Act 2013 this is read to mean the eldest child and heir);

- "if a man do violate the King's companion, or the King's eldest

daughter unmarried, or the wife of the King's eldest son and heir" (following the Succession to the Crown Act 2013 this is read to mean the eldest son if the heir);

- "if a man do levy war against our lord the King in his realm, or be

adherent to the King's enemies in his realm, giving to them aid and

comfort in the realm, or elsewhere"; and

- "if a man slea [slay] the chancellor, treasurer,

or the King's justices of the one bench or the other, justices in eyre,

or justices of assise, and all other justices assigned to hear and

determine, being in their places, doing their offices".

Another Act, the Treason Act 1702 (1 Anne stat. 2 c. 21), provides for a fifth category of treason, namely:

- "if any person or persons ... shall endeavour to deprive or

hinder any person who shall be the next in succession to the crown ...

from succeeding after the decease of her Majesty (whom God long

preserve) to the imperial crown of this realm and the dominions and

territories thereunto belonging".

By virtue of the Treason Act 1708, the law of treason in Scotland is the same as the law in England, save that in Scotland the slaying of the Lords of Session and Lords of Justiciary and counterfeiting the Great Seal of Scotland remain treason under sections 11 and 12 of the Treason Act 1708 respectively. Treason is a reserved matter about which the Scottish Parliament is prohibited from legislating. Two acts of the former Parliament of Ireland passed in 1537 and 1542 create further treasons which apply in Northern Ireland.

The penalty for treason was changed from death to a maximum of imprisonment for life under the Crime and Disorder Act 1998. Before 1998, the death penalty was mandatory, subject to the royal prerogative of mercy. Since the abolition of the death penalty for murder in 1965 an execution for treason was unlikely to have been carried out.

Treason laws were used against Irish insurgents before Irish independence. However, members of the Provisional IRA and other militant republican groups were not prosecuted or executed for treason for levying war against the British government during the Troubles. They, along with members of loyalist paramilitary groups, were jailed for murder, violent crimes or terrorist offences. William Joyce ("Lord Haw-Haw") was the last person to be put to death for treason, in 1946. (On the following day Theodore Schurch was executed for treachery, a similar crime, and was the last man to be executed for a crime other than murder in the UK.)

The

Indische Legion attached to the

German Army was created in 1941, mainly from disaffected Indian soldiers of the British Indian Army.

As to who can commit treason, it depends on the ancient notion of allegiance. As such, all British nationals (but not other Commonwealth citizens)

owe allegiance to the sovereign in right of the United Kingdom wherever

they may be, as do Commonwealth citizens and aliens present in the

United Kingdom at the time of the treasonable act (except diplomats and

foreign invading forces), those who hold a British passport however

obtained, and aliens who have lived in Britain and departed, but leaving

behind family and belongings.

International influence

The Treason Act 1695

enacted, among other things, a rule that treason could be proved only

in a trial by the evidence of two witnesses to the same offence. Nearly

one hundred years later this rule was incorporated into the U.S. Constitution, which requires two witnesses to the same overt act.

It also provided for a three-year time limit on bringing prosecutions

for treason (except for assassinating the king), another rule which has

been imitated in some common law countries.

The Sedition Act 1661

made it treason to imprison, restrain or wound the king. Although this

law was repealed in the United Kingdom in 1998, it still continues to

apply in some Commonwealth countries.

United States

The offense of treason exists at both federal and state levels. The

federal crime is defined in the Constitution as either levying war

against the United States or adhering to its enemies, and carries a

sentence of death or imprisonment and fine.

In the 1790s, opposition

political parties were new and not fully accepted. Government leaders

often considered their opponents to be traitors. Historian Ron Chernow reports that Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and President George Washington "regarded much of the criticism fired at their administration as disloyal, even treasonous, in nature." When the undeclared Quasi-War broke out with France in 1797–98, "Hamilton increasingly mistook dissent for treason and engaged in hyperbole." Furthermore, the Jeffersonian opposition party behaved the same way.

After 1801, with a peaceful transition in the political party in power,

the rhetoric of "treason" against political opponents diminished.

Federal

To avoid the abuses of the English law, the scope of treason was specifically restricted in the United States Constitution. Article III, section 3 reads as follows:

Treason against the United States,

shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their

Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of

Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act,

or on Confession in open Court.

The Congress shall have Power to declare the Punishment of Treason, but

no Attainder of Treason shall work Corruption of Blood, or Forfeiture except during the Life of the Person attainted.

The Constitution does not itself create the offense; it only restricts the definition (the first paragraph), permits the United States Congress

to create the offense, and restricts any punishment for treason to only

the convicted (the second paragraph). The crime is prohibited by

legislation passed by Congress. Therefore, the United States Code at 18 U.S.C. § 2381 states:

Whoever,

owing allegiance to the United States, levies war against them or

adheres to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort within the United

States or elsewhere, is guilty of treason and shall suffer death, or

shall be imprisoned not less than five years and fined under this title

but not less than $10,000; and shall be incapable of holding any office

under the United States.

The requirement of testimony of two witnesses was inherited from the British Treason Act 1695.

However, Congress has passed laws creating related offenses that

punish conduct that undermines the government or the national security,

such as sedition in the 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts, or espionage and sedition in the Espionage Act of 1917,

which do not require the testimony of two witnesses and have a much

broader definition than Article Three treason. Some of these laws are

still in effect. The well-known spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were charged with conspiracy to commit espionage, rather than treason.

Historical cases

In the United States, Benedict Arnold's name is considered synonymous with treason due to his collaboration with the British during the American Revolutionary War. This, however, occurred before the Constitution was written. Arnold became a general in the British Army, which protected him.

Since the Constitution came into effect, there have been fewer

than 40 federal prosecutions for treason and even fewer convictions.

Several men were convicted of treason in connection with the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion but were pardoned by President George Washington.

Burr trial

The most famous treason trial, that of Aaron Burr in 1807, resulted in acquittal. In 1807, on a charge of treason, Burr was brought to trial before the United States Circuit Court at Richmond, Virginia. The only physical evidence presented to the grand jury was General James Wilkinson's so-called letter from Burr, which proposed the idea of stealing land in the Louisiana Purchase. The trial was presided over by Chief Justice of the United States John Marshall,

acting as a circuit judge. Since no witnesses testified, Burr was

acquitted in spite of the full force of Jefferson's political influence

thrown against him. Immediately afterward, Burr was tried on a

misdemeanor charge and was again acquitted.

Civil War

During the American Civil War, treason trials were held in Indianapolis against Copperheads for conspiring with the Confederacy against the United States.

In addition to treason trials, the federal government passed new laws

that allowed prosecutors to try people for the charge of disloyalty.

Various legislation was passed, including the Conspiracies Act of

July 31, 1861. Because the law defining treason in the constitution

was so strict, new legislation was necessary to prosecute defiance of

the government. Many of the people indicted on charges of conspiracy were not taken to trial, but instead were arrested and detained.

In addition to the Conspiracies Act of July 31, 1861, in 1862,

the federal government went further to redefine treason in the context

of the civil war. The act that was passed is entitled "An Act to

Suppress Insurrection; to punish Treason and Rebellion, to seize and

confiscate the Property of Rebels, and for other purposes". It is

colloquially referred to as the "second Confiscation Act". The act

essentially lessened the punishment for treason. Rather than have death

as the only possible punishment for treason, the act made it possible

to give individuals lesser sentences.

Reconstruction

After

the Civil War the question was whether the United States government

would make indictments for treason against leaders of the Confederate States of America, as many people demanded. Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederate States,

was indicted and held in prison for two years. The indictments were

dropped on February 11, 1869, following the blanket amnesty noted below. When accepting Lee's surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, at Appomattox Courthouse, in April 1865, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant assured all Confederate soldiers and officers a blanket amnesty,

provided they returned to their homes and refrained from any further

acts of hostility, and subsequently other Union generals issued similar

terms of amnesty when accepting Confederate surrenders. All Confederate officials received a blanket amnesty issued by President Andrew Johnson on Christmas Day, 1868.

World War II

Iva Toguri, known as

Tokyo Rose, was tried for treason after World War II for her broadcasts to American troops.

In 1949 Iva Toguri D'Aquino was convicted of treason for wartime Radio Tokyo

broadcasts (under the name of "Tokyo Rose") and sentenced to ten years,

of which she served six. As a result of prosecution witnesses having

lied under oath, she was pardoned in 1977.

In 1952 Tomoya Kawakita, a Japanese-American dual citizen

was convicted of treason and sentenced to death for having worked as an

interpreter at a Japanese POW camp and having mistreated American

prisoners. He was recognized by a former prisoner at a department store

in 1946 after having returned to the United States. The sentence was

later commuted to life imprisonment and a $10,000 fine. He was released

and deported in 1963.

Cold War and after

The Cold War saw frequent talk linking treason with support for Communist-led causes. The most memorable of these came from Senator Joseph McCarthy, who used rhetoric about the Democrats as guilty of "twenty years of treason". As chosen chair of the Senate Permanent Investigations Subcommittee, McCarthy also investigated various government agencies for Soviet

spy rings; however, he acted as a political fact-finder rather than a

criminal prosecutor. The Cold War period saw no prosecutions for

explicit treason, but there were convictions and even executions for conspiracy to commit espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union, such as in the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg case.

On October 11, 2006, the United States government charged Adam Yahiye Gadahn for videos in which he appeared as a spokesman for al-Qaeda and threatened attacks on American soil. He was killed on January 19, 2015, in an unmanned aircraft (drone) strike in Waziristan, Pakistan.

Treason against U.S. states

Most states have treason provisions in their constitutions or statutes similar to those in the U.S. Constitution. The Extradition Clause specifically defines treason as an extraditable offense.

Thomas Jefferson in 1791 said that any Virginia official who cooperated with the federal Bank of the United States proposed by Alexander Hamilton was guilty of "treason" against the state of Virginia and should be executed. The Bank opened and no one was prosecuted.

Several persons have been prosecuted for treason on the state level. Thomas Dorr was convicted for treason against the state of Rhode Island for his part in the Dorr Rebellion, but was eventually granted amnesty. John Brown was convicted of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia for his part in the raid on Harpers Ferry, and was hanged. The Mormon prophet, Joseph Smith, was charged with treason against Missouri along with five others, at first in front of a state military court, but Smith was allowed to escape to Illinois after his case was transferred to a civilian court for trial on charges of treason and other crimes.

Smith was then later imprisoned for trial on charges of treason against

Illinois, but was murdered by a lynch mob while in jail awaiting trial.

Vietnam

The Constitution of Vietnam

proclaims that treason is the most serious crime. It is further

regulated in the country's 2015 Criminal Code with the 78th article:

- Any Vietnamese citizen acting in collusion with a foreign

country with a view to causing harm to the independence, sovereignty,

unity and territorial integrity of the Fatherland, the national defense

forces, the socialist regime or the State of the Socialist Republic of

Vietnam shall be sentenced to between twelve and twenty years of

imprisonment, life imprisonment or capital punishment.

- In the event of many extenuating circumstances, the offenders shall

be subject to between seven and fifteen years of imprisonment.

Also, according to the Law on Amnesty amended in November 2018, it is

impossible for those convicted for treason to be granted amnesty.

Muslim-majority countries

Early in Islamic history,

the only form of treason was seen as the attempt to overthrow a just

government or waging war against the State. According to Islamic

tradition, the prescribed punishment ranged from imprisonment to the

severing of limbs and the death penalty depending on the severity of the

crime. However, even in cases of treason the repentance of a person

would have to be taken into account.

Currently, the consensus among major Islamic schools is that apostasy (leaving Islam) is considered treason and that the penalty is death; this is supported not in the Quran but in hadith. This confusion between apostasy and treason almost certainly had its roots in the Ridda Wars, in which an army of rebel traitors led by the self-proclaimed prophet Musaylima attempted to destroy the caliphate of Abu Bakr.

In the 19th and early 20th century, the Iranian Cleric Sheikh Fazlollah Noori opposed the Iranian Constitutional Revolution

by inciting insurrection against them through issuing fatwas and

publishing pamphlets arguing that democracy would bring vice to the

country. The new government executed him for treason in 1909.

In Malaysia, it is treason to commit offences against the Yang di-Pertuan Agong's person, or to wage or attempt to wage war or abet the waging of war against the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, a Ruler or Yang di-Pertua Negeri.

All these offences are punishable by hanging, which derives from the

English treason acts (as a former British colony, Malaysia's legal

system is based on English common law).

Algeria

A young

Harki, an Algerian who served the French during the Algerian War, circa 1961

In Algeria, treason is defined as the following:

- attempts to change the regime or actions aimed at incitement

- destruction of territory, sabotage to public and economic utilities

- participation in armed bands or in insurrectionary movements

Bahrain

In Bahrain,

plotting to topple the regime, collaborating with a foreign hostile

country and threatening the life of the Emir are defined as treason and

punishable by death. The State Security Law of 1974

was used to crush dissent that could be seen as treasonous, which was

criticised for permitting severe human rights violations in accordance

with Article One:

If there is serious evidence that a

person has perpetrated acts, delivered statements, exercised

activities, or has been involved in contacts inside or outside the

country, which are of a nature considered to be in violation of the

internal or external security of the country, the religious and national

interests of the State, its social or economic system; or considered to

be an act of sedition that affects or can possibly affect the existing

relations between the people and Government, between the various

institutions of the State, between the classes of the people, or between

those who work in corporations propagating subversive propaganda or

disseminating atheistic principles; the Minister of Interior may order

the arrest of that person, committing him to one of Bahrain's prisons,

searching him, his residence and the place of his work, and may take any

measure which he deems necessary for gathering evidence and completing

investigations.

The period of detention may not exceed three years. Searches may only be

made and the measures provided for in the first paragraph may only be

taken upon judicial writ.

Palestine

In the areas controlled by the Palestinian National Authority, it is treason to give assistance to Israeli troops without the authorization of the Palestinian Authority or to sell land to Jews (irrespective of nationality) or non-Jewish Israeli citizens under the Palestinian Land Laws, as part of the PA's general policy of discouraging the expansion of Israeli settlements. Both crimes are capital offences subject to the death penalty, although the former provision has not often been enforced since the beginning of effective security cooperation between the Israel Defense Forces, Israel Police, and Palestinian National Security Forces since the mid-2000s (decade) under the leadership of Prime Minister Salam Fayyad. Likewise, in the Gaza Strip under the Hamas-led government, any sort of cooperation or assistance to Israeli security forces during military actions is also punishable by death.

Related offences

There are a number of other crimes against the state short of treason:

- Apostasy in Islam, considered treason in Islamic belief

- Compounding treason, dropping a prosecution for treason in exchange for money or money's worth

- Defection, or leaving the country, regarded in some communist countries (especially during the Cold War) as disloyalty to the state

- Espionage or spying

- Lèse majesté, insulting a head of state and a crime in some countries

- Misprision of treason, a crime consisting of the concealment of treason

- Sedition, inciting civil unrest or insurrection, or undermining the government

- Treachery, attacking a state regardless of allegiance

- Treason felony, a British offence tantamount to treason