Slavery in Britain existed before the Roman occupation and until the 11th century, when the Norman conquest of England resulted in the gradual merger of the pre-conquest institution of slavery into serfdom, and all slaves were no longer recognised separately in English law or custom. By the middle of the 12th century, the institution of slavery as it had existed prior to the Norman conquest had fully disappeared, but other forms of unfree servitude continued for some centuries.

British merchants were a significant force behind the Atlantic slave trade between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, but no legislation was ever passed in England that legalised slavery. In the Somerset case of 1772, Lord Mansfield ruled that, as slavery was not recognised by English law, James Somerset, a slave who had been brought to England and then escaped, could not be forcibly sent to Jamaica for sale, and he was set free. In Scotland colliery slaves were still in use until 1799 where an act was passed which established their freedom and made this slavery and bondage illegal.

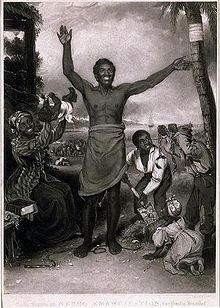

An influential abolitionist movement grew in Britain during the 18th and 19th century, until the Slave Trade Act 1807 abolished the slave trade in the British Empire, but it was not until the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 that the institution of slavery was abolished completely.

Despite being illegal, modern slavery still exists in Britain, as elsewhere, often following human trafficking from poorer countries, but also frequently targeting UK nationals.

Overview

Historically, Britons were enslaved in large numbers, typically by rich merchants and warlords who exported indigenous slaves from pre-Roman times, and by foreign invaders from the Roman Empire during the Roman Conquest of Britain.

A thousand years later, British merchants became major participants in the Atlantic slave trade in the early modern period. As part of the triangular trade-system, ship-owners transported enslaved West Africans to European possessions in the New World (especially to British colonies in the West Indies) to be sold there. The ships brought commodities back to Britain then exported goods to Africa. Some plantation owners brought slaves to Britain, where many of them ran away from their masters. After a long campaign for abolition led by Thomas Clarkson and (in the House of Commons) by William Wilberforce, Parliament prohibited dealing in slaves by passing the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which the Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron enforced. Britain used its influence to persuade other countries around the world to abolish the slave trade and to sign treaties to allow the Royal Navy to interdict slaving ships.

In 1772, Somerset v Stewart held that slavery had no basis in English law and was thus a violation of habeas corpus. This built on the earlier Cartwright case from the reign of Elizabeth I which had similarly held the concept of slavery was not recognised in English law. This case was generally taken at the time to have decided that the condition of slavery did not exist under English law. Legally ("de jure") slave owners could not win in court, and abolitionists provided legal help for enslaved black people. However actual ("de facto") slavery continued in Britain with ten to fourteen thousand slaves in England and Wales, who were mostly domestic servants. When slaves were brought in from the colonies they had to sign waivers that made them indentured servants while in Britain. Most modern historians generally agree that slavery continued in Britain into the late 18th century, finally disappearing around 1800.

Slavery elsewhere in the British Empire was not affected — indeed it grew rapidly especially in the Caribbean colonies. Slavery was abolished in the colonies by buying out the owners in 1833 by the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. Most slaves were freed, with exceptions and delays provided for the East India Company, Ceylon, and Saint Helena. These exceptions were eliminated in 1843.

The prohibition on slavery and servitude is now codified under Article 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights, in force since 1953 and incorporated directly into United Kingdom law by the Human Rights Act 1998. Article 4 of the Convention also bans forced or compulsory labour, with some exceptions such as a criminal penalty or military service.

Before 1066

From before Roman times, slavery was prevalent in Britain, with indigenous Britons being routinely exported. Following the Roman conquest of Britain, slavery was expanded and industrialised.

After the fall of Roman Britain, both the Angles and Saxons propagated the slave system. One of the earliest accounts of slaves from early medieval Britain come from the description of fair-haired boys from York seen in Rome by Pope Gregory the Great, in a biography written by an anonymous monk.

Vikings traded with Gaelic, Pict, Brythonic and Saxon kingdoms in between raiding them for slaves. Saxon slave traders sometimes worked in league with Norse traders, often selling Britons to the Irish. In 870, Vikings besieged and captured the stronghold of Alt Clut (the capital of the Kingdom of Strathclyde) and in 871 most of the site's inhabitants were taken, most probably by Olaf the White and Ivar the Boneless, to the Dublin slave markets. Maredudd ab Owain (d. 999) is said to have paid a large ransom for the return of 2,000 Welsh slaves.

Anglo-Saxon opinion eventually turned against the sale of slaves abroad: a law of Ine of Wessex stated that anyone selling his own countryman, whether bond or free, across the sea, was to pay his own weregild in penalty, even when the man sold was guilty of a crime. Nevertheless, legal penalties and economic pressures that led to default in payments maintained the supply of slaves, and in the 11th century there was still a slave trade operating out of Bristol, as a passage in the Vita Wulfstani makes clear.

The Bodmin manumissions, preserves the names and details of slaves freed in Bodmin (then the principal town of Cornwall) during the 9th and 10th centuries, indicating both that slavery existed in Cornwall at that time and that numerous Cornish slave-owners eventually set their slaves free.

Norman and Medieval England

According to the Domesday Book census, over 10% of England's population in 1086 were slaves.

While there was no legislation against slavery, William the Conqueror introduced a law preventing the sale of slaves overseas.

In 1102, the Church Council of London convened by Anselm issued a decree: "Let no one dare hereafter to engage in the infamous business, prevalent in England, of selling men like animals." However, the Council had no legislative powers, and no act of law was valid unless signed by the monarch.

Contemporary writers noted that the Scottish and Welsh took captives as slaves during raids, a practice which was no longer common in England by the 12th century. Some historians, like John Gillingham, have asserted that by about 1200, the institution of slavery was largely non-existent in the British Isles.

Other academics such as Judith Spicksley, have argued that forms of slavery did in fact continue in England between the 12th and 17th centuries, but under other terms such as "serfs", "villein" and "bondsmen", however the serf or villein differed from the slave in that they could not be purchased as a moveable object who could be removed from his land; meaning that instead serfdom was closer to the purchasing of rental titles today than to true slavery. Slavery did still occur though, as in the carrying away of over a thousand children from Wales to be "servants", which is recorded as taking place in 1401.

Transportation

Transportation to the colonies as a criminal or an indentured servant served as punishment for both great and petty crimes in England from the 17th century until well into the 19th century. A sentence could be for life or for a specific period. The penal system required convicts to work on government projects such as road construction, building works and mining, or assigned them to free individuals as unpaid labour. Women were expected to work as domestic servants and farm labourers. Like slaves, indentured servants could be bought and sold, could not marry without the permission of their owner, were subject to physical punishment, and saw their obligation to labour enforced by the courts. However, they did retain certain heavily restricted rights; this contrasts with slaves who had none.

A convict who had served part of his time might apply for a "ticket of leave", granting them some prescribed freedoms. This enabled some convicts to resume a more normal life, to marry and raise a family, and enabled a few to develop the colonies while removing them from the society. Exile was an essential component, and was thought to be a major deterrent to crime. Transportation was also seen as a humane and productive alternative to execution, which would most likely have been the sentence for many if transportation had not been introduced.

The transportation of English subjects overseas can be traced back to the English Vagabonds Act 1597. During the reign of Henry VIII, an estimated 72,000 people were put to death for a variety of crimes. An alternative practice, borrowed from the Spanish, was to commute the death sentence and allow the use of convicts as a labour force for the colonies. One of the first references to a person being transported comes in 1607 when "an apprentice dyer was sent to Virginia from Bridewell for running away with his master's goods." The Act was little used despite attempts by James I who, with limited success, tried to encourage its adoption by passing a series of Privy Council Orders in 1615, 1619 and 1620.

Transportation was seldom used as a criminal sentence until the Piracy Act 1717, "An Act for the further preventing Robbery, Burglary, and other Felonies, and for the more effectual Transportation of Felons, and unlawful Exporters of Wool; and for declaring the Law upon some Points relating to Pirates", established a seven-year penal transportation as a possible punishment for those convicted of lesser felonies, or as a possible sentence to which capital punishment might be commuted by royal pardon. Criminals were transported to North America from 1718 to 1776. When the American revolution made transportation to the Thirteen Colonies unfeasible, those sentenced to it were typically punished with imprisonment or hard labour instead. From 1787 to 1868, criminals convicted and sentenced under the Act were transported to the colonies in Australia.

After the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and subsequent Cromwellian invasion, the English Parliament passed the Act for the Settlement of Ireland 1652 which classified the Irish population into several categories according to their degree of involvement in the uprising and the subsequent war. Those who had participated in the uprising or assisted the rebels in any way were sentenced to be hanged and to have their property confiscated. Other categories were sentenced to banishment with whole or partial confiscation of their estates. While the majority of the resettlement took place within Ireland to the province of Connaught, perhaps as many as 50,000 were transported to the colonies in the West Indies and in North America. Irish, Welsh and Scottish people were sent to work on sugar plantations in Barbados during the time of Cromwell.

During the early colonial period, the Scots and the English, along with other western European nations, dealt with their "Gypsy problem" by transporting them as slaves in large numbers to North America and the Caribbean. Cromwell shipped Romanichal Gypsies as slaves to the southern plantations, and there is documentation of Gypsies being owned by former black slaves in Jamaica.

Long before the Highland Clearances, some chiefs, such as Ewen Cameron of Lochiel, sold some of their clans into indenture in North America. Their goal was to alleviate over-population and lack of food resources in the glens.

Numerous Highland Jacobite supporters, captured in the aftermath of the Battle of Culloden and rigorous Government sweeps of the Highlands, were imprisoned on ships on the River Thames. Some were sentenced to transportation to the Carolinas as indentured servants.

Slavery and bondage in Scottish collieries

For nearly two hundred years in the history of coal mining in Scotland, miners were bonded to their "maisters" by a 1606 Act "Anent Coalyers and Salters". The Colliers and Salters (Scotland) Act 1775 stated that "many colliers and salters are in a state of slavery and bondage" and announced emancipation; those starting work after 1 July 1775 would not become slaves, while those already in a state of slavery could, after 7 or 10 years depending on their age, apply for a decree of the Sheriff Court granting their freedom. Few could afford this, until a further law in 1799 established their freedom and made this slavery and bondage illegal.

Barbary pirates

From the 16th to the 19th centuries it is estimated that between 1 million and 1.25 million Europeans were captured and sold as slaves by Barbary pirates and Barbary slave traders from Tunis, Algiers and Tripoli (in addition to an unknown number captured by the Turkish and Moroccan pirates and slave traders) The slavers got their name from the Barbary Coast, that is, the Mediterranean shores of North Africa — what is now Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. There are reports of Barbary slave raids across Western Europe, including France, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, England and as far north as Iceland.

Villagers along the south coast of England petitioned the king to protect them from abduction by Barbary pirates. Item 20 of The Grand Remonstrance, a list of grievances against Charles I presented to him in 1641, contains the following complaint about Barbary pirates of the Ottoman Empire abducting English people into slavery:

And although all this was taken upon pretense of guarding the seas, yet a new unheard-of tax of ship-money was devised, and upon the same pretense, by both which there was charged upon the subject near £700,000 some years, and yet the merchants have been left so naked to the violence of the Turkish pirates, that many great ships of value and thousands of His Majesty's subjects have been taken by them, and do still remain in miserable slavery.

Enslaved Africans

The privateer Sir John Hawkins of Plymouth, a notable Elizabethan seafarer, is widely acknowledged to be "the Pioneer of the English Slave Trade". In 1554, Hawkins formed a slave-trading syndicate, a group of merchants. He sailed with three ships for the Caribbean via Sierra Leone, hijacked a Portuguese slave ship and sold the 300 slaves from it in Santo Domingo. During a second voyage in 1564, his crew captured 400 Africans and sold them at Rio de la Hacha in present-day Colombia, making a 60% profit for his financiers. A third voyage involved both buying slaves directly in Africa and capturing another Portuguese slave ship with its cargo; upon reaching the Caribbean, Hawkins sold all his slaves. On his return, he published a book entitled An Alliance to Raid for Slaves. It is estimated that Hawkins transported 1,500 enslaved Africans across the Atlantic during his four voyages of the 1560s, before stopping in 1568 after a battle with the Spanish in which he lost five of his seven ships. English involvement in the Atlantic slave trade only resumed in the 1640s after the country acquired an American colony (Virginia).

By the mid-18th century, London had the largest African population in Britain. The number of Black people living in Britain by that point has been estimated by historians to be roughly 10,000, though contemporary reports put that number as high as 20,000. Some Africans living in Britain would run away from their masters, many of whom responded by placing advertisements in newspapers offering rewards for the returns.

A number of former Black slaves managed to achieve prominence in 18th-century British society. Ignatius Sancho (1729–1780), known as "The Extraordinary Negro", opened his own grocer's shop in Westminster. He was famous for his poetry and music, and his friends included the novelist Laurence Sterne, David Garrick the actor and the Duke and Duchess of Montague. He is best known for his letters which were published after his death. Others, such as Olaudah Equiano and Ottobah Cugoano were equally well known, and along with Ignatius Sancho were active in the British abolition campaign.

Triangular trade

By the 18th century, the slave trade became a profitable economic activity for such port cities as Bristol, Liverpool and Glasgow, engaged in the so-called "Triangular trade". Merchant ships set out from Britain, loaded with trade goods which were exchanged on the West African shores for slaves captured by local rulers from deeper inland; the slaves were transported through the infamous "Middle Passage" across the Atlantic, and were sold at considerable profit for labour in plantations. The ships were loaded with export crops and commodities, the products of slave labour, such as cotton, sugar and rum, and returned to Britain to sell the items.

The Isle of Man

was involved in the transatlantic African slave trade. Goods from the

slave trade were bought and sold on the Isle of Man, and Manx merchants,

seamen, and ships were involved in the trade.

Judicial decisions

No legislation was ever passed in England that legalised slavery, unlike the Portuguese Ordenações Manuelinas (1481–1514), the Dutch East India Company Ordinances (1622), and France's Code Noir (1685), and this caused confusion when English people brought home slaves they had legally purchased in the colonies. In Butts v. Penny (1677) 2 Lev 201, 3 Keb 785, an action was brought to recover the value of 10 slaves who had been held by the plaintiff in India. The court held that an action for trover would lie in English law, because the sale of non-Christians as slaves was common in India. However, no judgment was delivered in the case.

An English court case of 1569 involving Cartwright who had bought a slave from Russia ruled that English law could not recognise slavery. This ruling was overshadowed by later developments, particularly in the Navigation Acts, but was upheld by the Lord Chief Justice in 1701 when he ruled that a slave became free as soon as he arrived in England.

Agitation saw a series of judgments repulse the tide of slavery. In Smith v. Gould (1705–07) 2 Salk 666, John Holt stated that by "the common law no man can have a property in another". (See the "infidel rationale".)

In 1729, the Attorney General, Philip Yorke, and Solicitor General of England, Charles Talbot, issued the Yorke–Talbot slavery opinion, expressing their view that the legal status of any enslaved individual did not change once they set foot in Britain; i.e., they would not automatically become free. This was done in response to the concerns that Holt's decision in Smith v. Gould raised. Slavery was also accepted in Britain's many colonies.

Lord Henley LC said in Shanley v. Harvey (1763) 2 Eden 126, 127 that as "soon as a man sets foot on English ground he is free".

After R v. Knowles, ex parte Somersett (1772) 20 State Tr 1 the law remained unsettled, although the decision was a significant advance for, at the least, preventing the forceable removal of anyone from England, whether or not a slave, against his will. A man named James Somersett was enslaved by a Boston customs officer. They came to England, and Somersett escaped. Captain Knowles captured him and took him on his boat bound for Jamaica. Three British abolitionists, saying they were his "godparents", applied for a writ of habeas corpus. One of Somersett's lawyers, Francis Hargrave, stated "In 1569, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, a lawsuit was brought against a man for beating another man he had bought as a slave overseas. The record states, 'That in the 11th [year] of Elizabeth [1569], one Cartwright brought a slave from Russia and would scourge him; for which he was questioned; and it was resolved, that England was too pure an air for a slave to breathe in'." He argued that the court had ruled in Cartwright's case that English common law made no provision for slavery, and without a basis for its legality, slavery would otherwise be unlawful as false imprisonment and/or assault. In his judgment of 22 June 1772, Lord Chief Justice William Murray, Lord Mansfield, of the Court of King's Bench, started by talking about the capture and forcible detention of Somersett. He finished with:

So high an act of dominion must be recognised by the law of the country where it is used. The power of a master over his slave has been exceedingly different, in different countries.

The state of slavery is of such a nature, that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political, but only by positive law, which preserves its force long after the reasons, occasion, and time itself from whence it was created, is erased from memory.

It is so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law. Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from the decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged.

Several different reports of Mansfield's decision appeared. Most disagree as to what was said. The decision was only given orally; no formal written record of it was issued by the court. Abolitionists widely circulated the view that it was declared that the condition of slavery did not exist under English law, although Mansfield later said that all that he decided was that a slave could not be forcibly removed from England against his will.

After reading about Somersett's Case, Joseph Knight, an enslaved African who had been purchased by his master John Wedderburn in Jamaica and brought to Scotland, left him. Married and with a child, he filed a freedom suit, on the grounds that he could not be held as a slave in Great Britain. In the case of Knight v. Wedderburn (1778), Wedderburn said that Knight owed him "perpetual servitude". The Court of Sessions of Scotland ruled against him, saying that chattel slavery was not recognised under the law of Scotland, and slaves could seek court protection to leave a master or avoid being forcibly removed from Scotland to be returned to slavery in the colonies.

Abolition

The abolitionist movement was led by Quakers and other Non-conformists, but the Test Act prevented them from becoming Members of Parliament. William Wilberforce, a member of the House of Commons as an independent, became the Parliamentary spokesman for the abolition of the slave trade in Britain. His conversion to Evangelical Christianity in 1784 played a key role in interesting him in this social reform. William Wilberforce's Slave Trade Act 1807 abolished the slave trade in the British Empire. It was not until the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 that the institution finally was abolished, but on a gradual basis. Since land owners in the British West Indies were losing their unpaid labourers, they received compensation totalling £20 million. Former slaves received no compensation.

The Royal Navy established the West Africa Squadron (or Preventative Squadron) at substantial expense in 1808 after Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act. The squadron's task was to suppress the Atlantic slave trade by patrolling the coast of West Africa, preventing the slave trade by force of arms, including the interception of slave ships from Europe, the United States, the Barbary pirates, West Africa and the Ottoman Empire.

The Church of England was implicated in slavery. Slaves were owned by the Anglican Church's Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPGFP), which had sugar plantations in the West Indies. When slaves were emancipated by Act of the British Parliament in 1834, the British government paid compensation to slave owners. The Bishop of Exeter, Henry Phillpotts, and three business colleagues acted as trustees for John Ward, 1st Earl of Dudley when he received compensation for 665 slaves. The compensation of British slaveholders was almost £17 billion in current money.

Economic impact of slavery

Historians and economists have debated the economic effects of slavery for Great Britain and the North American colonies. Some analysts, such as Eric Williams, suggest that it allowed the formation of capital that financed the Industrial Revolution, although the evidence is inconclusive. Slave labour was integral to early settlement of the colonies, which needed more people for labour and other work. Also, slave labour produced the major consumer goods that were the basis of world trade during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries: coffee, cotton, rum, sugar, and tobacco. Slavery was far more important to the profitability of plantations and the economy in the American South; and the slave trade and associated businesses were important to both New York and New England.

Others, such as economist Thomas Sowell, have noted instead that at the height of the Atlantic slave trade in the 18th century, profits by British slave traders would have only amounted to 2 percent of British domestic investment. In 1995, a random anonymous survey of 178 members of the Economic History Association found that out of the 40 propositions about the economic history of the United States that were surveyed, the group of propositions most disputed by economic historians and economists were those about the postbellum economy of the American South (along with the Great Depression). The only exception was the proposition initially put forward by historian Gavin Wright that the "modern period of the South's economic convergence to the level of the North only began in earnest when the institutional foundations of the southern regional labor market were undermined, largely by federal farm and labor legislation dating from the 1930s." 62 percent of economists (24 percent with and 38 percent without provisos) and 73 percent of historians (23 percent with and 50 percent without provisos) agreed with this statement.

Additionally, economists Peter H. Lindert and Jeffrey G. Williamson, in a pair of articles published in 2012 and 2013, found that, despite the Southern United States initially having per capita income roughly double that of the Northern United States in 1774, incomes in the South had declined 27% by 1800 and continued to decline over the next four decades, while the economies in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states vastly expanded. By 1840, per capita income in the South was well behind the Northeast and the national average (Note: this is also true in the early 21st century). Reiterating an observation made by Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America, Thomas Sowell also notes that like in Brazil, the states where slavery in the United States was concentrated ended up poorer and less populous at the end of the slavery than the states that had abolished slavery in the United States.

While some historians have suggested slavery was necessary for the Industrial Revolution (on the grounds that American slave plantations produced most of the raw cotton for the British textiles market and the British textiles market was the vanguard of the Industrial Revolution), historian Eric Hilt has noted that it is not clear if this is actually true; there is no evidence that cotton could not have been mass-produced by yeoman farmers rather than slave plantations if the latter had not existed (as their existence tended to force yeoman farmers into subsistence farming) and there is some evidence that they certainly could have. The soil and climate of the American South were excellent for growing cotton, so it is not unreasonable to postulate that farms without slaves could have produced substantial amounts of cotton; even if they did not produce as much as the plantations did, it could still have been enough to serve the demand of British producers. Similar arguments have been made by other historians. Additionally, Thomas Sowell has noted, citing historians Clement Eaton and Eugene Genovese, that three-quarters of Southern white families owned no slaves at all. Most slaveholders lived on farms rather than plantations, and few plantations were as large as the fictional ones depicted in Gone with the Wind.

In 2006, the then British Prime Minister, Tony Blair, expressed his deep sorrow over the slave trade, which he described as "profoundly shameful". Some campaigners had demanded reparations from the former slave trading nations.

In recent years, several institutions have begun to evaluate their own links with slavery. For instance, English Heritage produced a book on the extensive links between slavery and British country houses in 2013, Jesus College has a working group to examine the legacy of slavery within the college, and the Church of England, the Bank of England, Lloyd's of London and Greene King have all apologised for their historic links to slavery.

University College London has developed a database examining the commercial, cultural, historical, imperial, physical and political legacies of slavery in Britain.

Modern slavery

Much modern slavery in the UK derives from the human trafficking of children and adults from parts of Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe and elsewhere for purposes such as sexual slavery, forced labour, and domestic servitude. People living in the UK are also commonly targeted. British citizens accounted for 31% (3,952) of all recorded potential victims in 2021, when they represented the most frequently referred nationality. Forced labour is a leading type of modern slavery in adults. County lines drug trafficking has become a leading form of criminal child exploitation. Males have been found to be affected more often, both among adults and children.

As modern slavery is a hidden crime, its true prevalence is difficult to measure. In 2018, the Global Slavery Index estimated that there were about 136 thousand victims in the UK (a prevalence of 2.1 persons per 1,000 population). Research published in 2015, following the announcement of the government's 'Modern Slavery Strategy', had estimated the number of potential victims of modern slavery in the UK to be around 10–13 thousand, of whom roughly 7–10 thousand were currently unrecorded (given that 2,744 confirmed cases were known to the National Crime Agency)