The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states which were most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the war, the region suffered economic hardship and was a major site of racial tension during and after the Reconstruction era. Before 1945, the Deep South was often referred to as the "Cotton States" since cotton was the primary cash crop for economic production. The civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s helped usher in a new era, sometimes referred to as the New South.

Usage

The term "Deep South" is defined in a variety of ways:

- Most definitions include the following states: Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina.

- Texas, and Florida are sometimes included, due to being peripheral states, having coastlines with the Gulf of Mexico, their history of slavery, large African American populations, and being part of the historical Confederate States of America. The eastern part of Texas is the westernmost extension of the Deep South, while North Florida is also part of the Deep South region, typically the area north of Ocala.

- Tennessee, particularly West Tennessee, is sometimes included due to its history of slavery, its prominence in cotton production during the antebellum period, and cultural similarity to the Mississippi Delta region.

- Arkansas is sometimes included or considered to be "in the peripheral" or Rim South rather than the Deep South.

- The seven states that seceded from the United States before the firing on Fort Sumter and the start of the American Civil War, which originally formed the Confederate States of America. In order of secession, they are South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. The first six states to secede were those that, percentage-wise, held the largest number of slaves. Ultimately, the Confederacy included eleven states.

- A large part of the original "Cotton Belt" is sometimes included in Deep South terminology. This was considered to extend from eastern North Carolina to Georgia, through the Gulf States as far west as East Texas, including West Tennessee, eastern Arkansas, and up the Mississippi embayment.

- The inner core of the Deep South, characterized by very rich black soil that supported cotton plantations, is a geological formation known as the Black Belt. The Black Belt has since become better known as a sociocultural region; in this context it is a term used for much of the Cotton Belt, which had a high percentage of African-American slave labor.

Origins

Although often used in history books to refer to the seven states that originally formed the Confederacy, the term "Deep South" did not come into general usage until long after the Civil War ended. For at least the remainder of the 19th century, "Lower South" was the primary designation for those states. When "Deep South" first began to gain mainstream currency in print in the middle of the 20th century, it applied to the states and areas of South Carolina, Georgia, southern Alabama, northern Florida, Mississippi, northern Louisiana, West Tennessee, southern Arkansas, and eastern Texas, all historical areas of cotton plantations and slavery. This was the part of the South many considered the "most Southern."

Later, the general definition expanded to include all of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, as well as often taking in bordering areas of West Tennessee, East Texas and North Florida. In its broadest application, the Deep South is considered to be "an area roughly coextensive with the old cotton belt, from eastern North Carolina through South Carolina, west into East Texas, with extensions north and south along the Mississippi."

Early economics

After the Civil War, the region was economically poor. After Reconstruction ended in 1877, a small fraction of the white population composed of wealthy landowners, merchants and bankers controlled the economy and, largely, the politics. Most white farmers were poor and had to do manual work on their farms to survive. As prices fell, farmers' work became harder and longer because of a change from largely self-sufficient farms, based on corn and pigs, to the growing of a cash crop of cotton or tobacco. Cotton cultivation took twice as many hours of work as raising corn. The farmers lost their freedom to determine what crops they would grow, ran into increasing indebtedness, and many were forced into tenancy or into working for someone else. Some out-migration occurred, especially to Texas, but over time, the population continued to grow and the farms were subdivided smaller and smaller. Growing discontent helped give rise to the Populist movement in the early 1890s. It represented a sort of class warfare, in which the poor farmers sought to gain more of an economic and political voice.

From Reconstruction through the Civil Rights Movement

After 1950, the region became a major epicenter of the Civil Rights Movement, including: the emergence of a young (25 year old) new pastor of a local church, Martin Luther King Jr., the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott, the 1956 Sugar Bowl Riots, the 1960 founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the 1964 Freedom Summer.

Major cities and urban areas

The Deep South has three major Metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) located solely within its boundaries, with populations exceeding 1,000,000 residents (Four including Memphis). Atlanta, the 9th largest metro area in the United States, is the Deep South's largest population center, followed by Memphis, New Orleans, and Birmingham.

People

In the 1980 census, of people who identified solely by one European national ancestry, most European Americans identified as being of English ancestry in every Southern state except Louisiana, where more people identified as having French ancestry. A significant number also have Irish and Scotch-Irish ancestry.

With regards to people in the Deep South who reported only a single European-American ancestry group, the 1980 census showed the following self-identification in each state in this region:

- Alabama – 857,864 persons out of a total of 2,165,653 people in the state identified as "English," making them 41% of the state and the largest national ancestry group at the time by a wide margin.

- Georgia – 1,132,184 out of 3,009,486 people identified as "English," making them 37.62% of the state's total.

- Mississippi – 496,481 people out of 1,551,364 people identified as "English," making them 32.00% of the total, the largest national group by a wide margin.

- Florida – 1,132,033 people out of 5,159,967 identified "English" as their only ancestry group, making them 21.94% of the total.

- Louisiana – 440,558 people out of 2,319,259 people identified only as "English," making them 19.00% of the total people and the second-largest ancestry group in the state at the time. Those who wrote only "French" were 480,711 people out of 2,319,259 people, or 20.73% of the total state population.

- South Carolina – 578,338 people out of 1,706,966 identified as "English," making them 33.88% of the total at the time.

- Texas – 1,639,322 people identified as "English" only out of a total of 7,859,393 people, making them 20.86% of the total people in the state and the largest ancestry group by a large margin.

These figures do not take into account people who identified as "English" and another ancestry group. When the two were added together, people who self-identified as being English with other ancestry, made up an even larger portion of southerners. South Carolina was settled earlier than other states commonly classified as the Deep South. Its population in 1980 included 578,338 people out of 1,706,966 people, who identified as "English" only, making them 33.88% of the total population, the largest national ancestry group by a wide margin.

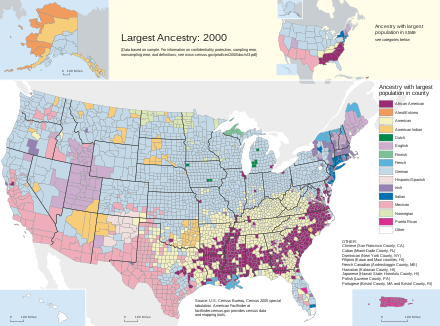

The map to the right was prepared by the Census Bureau from the 2000 census; it shows the predominant ancestry in each county as self-identified by residents themselves. Note: The Census said that areas with the largest "American"-identified ancestry populations, were mostly settled by descendants of English and others from the British Isles, French, Germans and later Italians. Those with African ancestry tended to identify as African American, although some African Americans also have some British or Northern European ancestors as well.

As of 2003, the majority of African-descended Americans in the South live in the Black Belt geographic area.

Hispanic and Latino Americans largely started arriving in the Deep South during the 1990s, and their numbers have grown rapidly. Politically they have not been very active.

Politics

Political expert Kevin Phillips states that, "From the end of Reconstruction until 1948, the Deep South Black Belts, where only whites could vote, were the nation's leading Democratic Party bastions."

From the late 1870s to the mid-1960s, conservative whites of the Deep South held control of state governments and overwhelmingly identified with and supported the Democratic Party. The most powerful leaders belonged to the party's moderate-to-conservative wing. The Republican Party would only control mainly mountain districts in Southern Appalachia, on the fringe of the Deep South, during the "Solid South" period.

At the turn of the 20th century, all Southern states, starting with Mississippi in 1890, passed new constitutions and other laws that effectively disenfranchised the great majority of blacks and sometimes many poor whites as well. Blacks were excluded subsequently from the political system entirely. The white Democratic-dominated state legislatures passed Jim Crow laws to impose white supremacy, including caste segregation of public facilities. In politics, the region became known for decades as the "Solid South." While this disenfranchisement was enforced, all of the states in this region were mainly one-party states dominated by white Southern Democrats. Southern representatives accrued outsized power in the Congress and the national Democratic Party, as they controlled all the seats apportioned to southern states based on total population, but only represented the richer subset of their white populations.

Major demographic changes would ensue in the 20th century. During the two waves of the Great Migration (1916–1970), a total of six million African Americans left the South for the Northeast, Midwest, and West, to escape the oppression and violence in the South. Beginning with the Goldwater–Johnson election of 1964, a significant contingent of white conservative voters in the Deep South stopped supporting national Democratic Party candidates and switched to the Republican Party. They still would vote for many Democrats at the state and local level into the 1990s. Studies of the Civil Rights Movement often highlight the region. Political scientist Seth McKee concluded that in the 1964 presidential election, "Once again, the high level of support for Goldwater in the Deep South, and especially their Black Belt counties, spoke to the enduring significance of white resistance to black progress."

White southern voters consistently voted for the Democratic Party for many years to hold onto Jim Crow Laws. Once Franklin D. Roosevelt came to power in 1932, the limited southern electorate found itself supporting Democratic candidates who frequently did not share its views. Journalist Matthew Yglesias argues:

The weird thing about Jim Crow politics is that white southerners with conservative views on taxes, moral values, and national security would vote for Democratic presidential candidates who didn't share their views. They did that as part of a strategy for maintaining white supremacy in the South.

Kevin Phillips states that, "Beginning in 1948, however, the white voters of the Black Belts shifted partisan gears and sought to lead the Deep South out of the Democratic Party. Upcountry, pineywoods and bayou voters felt less hostility towards the New Deal and Fair Deal economic and caste policies which agitated the Black Belts, and for another decade, they kept The Deep South in the Democratic presidential column.

Phillips emphasizes the three-way 1968 presidential election:

Wallace won very high support from Black Belt whites and no support at all from Black Belt Negroes. In the Black Belt counties of the Deep South, racial polarization was practically complete. Negroes voted for Hubert Humphrey, whites for George Wallace. GOP nominee Nixon garnered very little backing and counties where Barry Goldwater had captured 90 percent to 100 percent of the vote in 1964.

The Republican Party in the South had been crippled by the disenfranchisement of blacks, and the national party was unable to relieve their past with the South where Reconstruction was negatively viewed. During the Great Depression and the administration of Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, some New Deal measures were promoted as intending to aid African Americans across the country and in the poor rural South, as well as poor whites. In the post-World War II era, Democratic Party presidents and national politicians began to support desegregation and other elements of the Civil Rights Movement, from President Harry S. Truman's desegregating the military, to John F. Kennedy's support for non-violent protests. These efforts culminated in Lyndon B. Johnson's important work in gaining Congressional approval for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. Since then, upwards of 90 percent of African Americans in the South have voted for the Democratic Party, including 93 percent for Obama in 2012, though this dropped to 88 percent for Hillary Clinton in 2016.

Late 20th century to present

Historian Thomas Sugrue attributes the political and cultural changes, along with the easing of racial tensions, as the reason why Southern voters began to vote for Republican national candidates, in line with their political ideology. Since then, white Deep South voters have tended to vote for Republican candidates in most presidential elections. Times the Democratic Party has won in the Deep South since the late 20th century include: the 1976 election when Georgia native Jimmy Carter received the Democratic nomination, the 1980 election when Carter won Georgia, the 1992 election when Arkansas native and former governor Bill Clinton won Georgia, Tennessee, Louisiana, and Arkansas, the 1996 election when the incumbent president Clinton again won Louisiana, Tennessee and Arkansas, and when Georgia was won by Joe Biden in the 2020 United States presidential election.

In 1995, Georgia Republican Newt Gingrich was elected by representatives of a Republican-dominated House as Speaker of the House.

Since the 1990s the white majority has continued to shift toward Republican candidates at the state and local levels. This trend culminated in 2014 when the Republicans swept every statewide office in the Deep South region midterm elections. As a result, the Republican party came to control all the state legislatures in the region, as well as all House seats that were not representing majority-minority districts.

Presidential elections in which the Deep South diverged noticeably from the Upper South occurred in 1928, 1948, 1964, 1968, and, to a lesser extent, in 1952, 1956, 1992, and 2008. Former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee fared well in the Deep South in the 2008 Republican primaries, losing only one state (South Carolina) while running (he had dropped out of the race before the Mississippi primary).

In the 2020 presidential election, the state of Georgia was considered a toss-up state hinting at a possible Democratic shift in the area. It ultimately voted Democratic, in favor of Joe Biden. During the 2021 January Senate runoff elections, Georgia also voted for two Democrats, Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock. However, Georgia still maintains a Republican lean with a PVI rating of R+3 in line with its Deep South neighbors, with Republicans currently controlling every Georgia statewide office, its Supreme Court, and its legislature.

States

From colonial times to the early-twentieth century, much of the Lower South had a black majority. Three Southern states had populations that were majority-black: Louisiana (from 1810 until about 1890), South Carolina (until the 1920s), and Mississippi (from the 1830s to the 1930s). In the same period, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida had populations that were nearly 50% black, while Maryland, North Carolina, and Virginia had black populations approaching or exceeding 40%. Texas' black population reached 30%.

The demographics of these states changed markedly from the 1890s through the 1950s, as two waves of the Great Migration led more than 6,500,000 African-Americans to abandon the economically depressed, segregated Deep South in search of better employment opportunities and living conditions, first in Northern and Midwestern industrial cities, and later west to California. One-fifth of Florida's black population had left the state by 1940, for instance. During the last thirty years of the twentieth century into the twenty-first century, scholars have documented a reverse New Great Migration of black people back to southern states, but typically to destinations in the New South, which have the best jobs and developing economies.

The District of Columbia, one of the magnets for black people during the Great Migration, was long the sole majority-minority federal jurisdiction in the continental U.S. The black proportion has declined since the 1990s due to gentrification and expanding opportunities, with many black people moving to southern states such as Texas, Georgia, Florida, and Maryland and others migrating to jobs in states of the New South in a reverse of the Great Migration.

Transportation

- U.S. Route 90 runs from Van Horn, Texas to Jacksonville, Florida.

- U.S. Route 11 runs through the Deep South to the Canadian border in New York.

- Interstate 10 is a major transcontinental east-west highway that travels through the far southern portion of the Deep South, with its eastern terminus at I-95 in Jacksonville, Florida.

- Interstate 55 is a major north-south route traveling from Chicago, Illinois to New Orleans, Louisiana. The interstate travels throught the Deep South cities of Memphis, Jackson, and New Orleans.

- Interstate 40 is a major transcontinental east-west route that travels from Barstow, California to Wilmington, North Carolina. It meets Interstate 55 in Memphis.

- Interstate 49 is an partially complete interstate running north-south centrally in the United States. It runs currently in the Deep South from Texarkana, Arkansas through Shreveport, and Alexandria to Lafayette, Louisiana.

- Interstate 20 runs from West Texas to Florence, South Carolina. It travels through the Deep South cities of Shreveport, Jackson, Birmingham, Atlanta, Augusta, and Columbia.