From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A thermite reaction using iron(III) oxide. The sparks flying outwards are globules of molten iron trailing smoke in their wake.

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the transformation of one set of chemical substances to another.[1] Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the positions of electrons in the forming and breaking of chemical bonds between atoms, with no change to the nuclei (no change to the elements present), and can often be described by a chemical equation. Nuclear chemistry is a sub-discipline of chemistry that involves the chemical reactions of unstable and radioactive elements where both electronic and nuclear changes can occur.

The substance (or substances) initially involved in a chemical reaction are called reactants or reagents. Chemical reactions are usually characterized by a chemical change, and they yield one or more products, which usually have properties different from the reactants. Reactions often consist of a sequence of individual sub-steps, the so-called elementary reactions, and the information on the precise course of action is part of the reaction mechanism. Chemical reactions are described with chemical equations, which symbolically present the starting materials, end products, and sometimes intermediate products and reaction conditions.

Chemical reactions happen at a characteristic reaction rate at a given temperature and chemical concentration. Typically, reaction rates increase with increasing temperature because there is more thermal energy available to reach the activation energy necessary for breaking bonds between atoms.

Reactions may proceed in the forward or reverse direction until they go to completion or reach equilibrium. Reactions that proceed in the forward direction to approach equilibrium are often described as spontaneous, requiring no input of free energy to go forward. Non-spontaneous reactions require input of free energy to go forward (examples include charging a battery by applying an external electrical power source, or photosynthesis driven by absorption of electromagnetic radiation in the form of sunlight).

Different chemical reactions are used in combinations during chemical synthesis in order to obtain a desired product. In biochemistry, a consecutive series of chemical reactions (where the product of one reaction is the reactant of the next reaction) form metabolic pathways. These reactions are often catalyzed by protein enzymes. Enzymes increase the rates of biochemical reactions, so that metabolic syntheses and decompositions impossible under ordinary conditions can occur at the temperatures and concentrations present within a cell.

The general concept of a chemical reaction has been extended to reactions between entities smaller than atoms, including nuclear reactions, radioactive decays, and reactions between elementary particles as described by quantum field theory.

History

Antoine Lavoisier developed the theory of combustion as a chemical reaction with oxygen

Chemical reactions such as combustion in fire, fermentation and the reduction of ores to metals were known since antiquity. Initial theories of transformation of materials were developed by Greek philosophers, such as the Four-Element Theory of Empedocles stating that any substance is composed of the four basic elements – fire, water, air and earth. In the Middle Ages, chemical transformations were studied by Alchemists. They attempted, in particular, to convert lead into gold, for which purpose they used reactions of lead and lead-copper alloys with sulfur.[2]

The production of chemical substances that do not normally occur in nature has long been tried, such as the synthesis of sulfuric and nitric acids attributed to the controversial alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān. The process involved heating of sulfate and nitrate minerals such as copper sulfate, alum and saltpeter. In the 17th century, Johann Rudolph Glauber produced hydrochloric acid and sodium sulfate by reacting sulfuric acid and sodium chloride. With the development of the lead chamber process in 1746 and the Leblanc process, allowing large-scale production of sulfuric acid and sodium carbonate, respectively, chemical reactions became implemented into the industry. Further optimization of sulfuric acid technology resulted in the contact process in the 1880s,[3] and the Haber process was developed in 1909–1910 for ammonia synthesis.[4]

From the 16th century, researchers including Jan Baptist van Helmont, Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton tried to establish theories of the experimentally observed chemical transformations. The phlogiston theory was proposed in 1667 by Johann Joachim Becher. It postulated the existence of a fire-like element called "phlogiston", which was contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. This proved to be false in 1785 by Antoine Lavoisier who found the correct explanation of the combustion as reaction with oxygen from the air.[5]

Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac recognized in 1808 that gases always react in a certain relationship with each other. Based on this idea and the atomic theory of John Dalton, Joseph Proust had developed the law of definite proportions, which later resulted in the concepts of stoichiometry and chemical equations.[6]

Regarding the organic chemistry, it was long believed that compounds obtained from living organisms were too complex to be obtained synthetically. According to the concept of vitalism, organic matter was endowed with a "vital force" and distinguished from inorganic materials. This separation was ended however by the synthesis of urea from inorganic precursors by Friedrich Wöhler in 1828. Other chemists who brought major contributions to organic chemistry include Alexander William Williamson with his synthesis of ethers and Christopher Kelk Ingold, who, among many discoveries, established the mechanisms of substitution reactions.

Equations

Chemical equations are used to graphically illustrate chemical reactions. They consist of chemical or structural formulas of the reactants on the left and those of the products on the right. They are separated by an arrow (→) which indicates the direction and type of the reaction; the arrow is read as the word "yields".[7] The tip of the arrow points in the direction in which the reaction proceeds. A double arrow (⇌) pointing in opposite directions is used for equilibrium reactions. Equations should be balanced according to the stoichiometry, the number of atoms of each species should be the same on both sides of the equation. This is achieved by scaling the number of involved molecules (

and

and  in a schematic example below) by the appropriate integers a, b, c and d.[8]

in a schematic example below) by the appropriate integers a, b, c and d.[8]Elementary reactions

The elementary reaction is the smallest division into which a chemical reaction can be decomposed, it has no intermediate products.[10] Most experimentally observed reactions are built up from many elementary reactions that occur in parallel or sequentially. The actual sequence of the individual elementary reactions is known as reaction mechanism. An elementary reaction involves a few molecules, usually one or two, because of the low probability for several molecules to meet at a certain time.[11]

Isomerization of azobenzene, induced by light (hν) or heat (Δ)

The most important elementary reactions are unimolecular and bimolecular reactions. Only one molecule is involved in a unimolecular reaction; it is transformed by an isomerization or a dissociation into one or more other molecules. Such reactions require the addition of energy in the form of heat or light. A typical example of a unimolecular reaction is the cis–trans isomerization, in which the cis-form of a compound converts to the trans-form or vice versa.[12]

In a typical dissociation reaction, a bond in a molecule splits (ruptures) resulting in two molecular fragments. The splitting can be homolytic or heterolytic. In the first case, the bond is divided so that each product retains an electron and becomes a neutral radical. In the second case, both electrons of the chemical bond remain with one of the products, resulting in charged ions. Dissociation plays an important role in triggering chain reactions, such as hydrogen–oxygen or polymerization reactions.

- Dissociation of a molecule AB into fragments A and B

Chemical equilibrium

Most chemical reactions are reversible, that is they can and do run in both directions. The forward and reverse reactions are competing with each other and differ in reaction rates. These rates depend on the concentration and therefore change with time of the reaction: the reverse rate gradually increases and becomes equal to the rate of the forward reaction, establishing the so-called chemical equilibrium. The time to reach equilibrium depends on such parameters as temperature, pressure and the materials involved, and is determined by the minimum free energy. In equilibrium, the Gibbs free energy must be zero. The pressure dependence can be explained with the Le Chatelier's principle. For example, an increase in pressure due to decreasing volume causes the reaction to shift to the side with the fewer moles of gas.[13]The reaction yield stabilizes at equilibrium, but can be increased by removing the product from the reaction mixture or changed by increasing the temperature or pressure. A change in the concentrations of the reactants does not affect the equilibrium constant, but does affect the equilibrium position.

Thermodynamics

Chemical reactions are determined by the laws of thermodynamics. Reactions can proceed by themselves if they are exergonic, that is if they release energy. The associated free energy of the reaction is composed of two different thermodynamic quantities, enthalpy and entropy:[14]-

.

- G: free energy, H: enthalpy, T: temperature, S: entropy, Δ: difference(change between original and product)

;

Changes in temperature can also reverse the direction tendency of a reaction. For example, the water gas shift reaction

Reactions can also be characterized by the internal energy which takes into account changes in the entropy, volume and chemical potential. The latter depends, among other things, on the activities of the involved substances.[16]

-

- U: internal energy, S: entropy, p: pressure, μ: chemical potential, n: number of molecules, d: small change sign

Kinetics

The speed at which reactions takes place is studied by reaction kinetics. The rate depends on various parameters, such as:- Reactant concentrations, which usually make the reaction happen at a faster rate if raised through increased collisions per unit time. Some reactions, however, have rates that are independent of reactant concentrations. These are called zero order reactions.

- Surface area available for contact between the reactants, in particular solid ones in heterogeneous systems. Larger surface areas lead to higher reaction rates.

- Pressure – increasing the pressure decreases the volume between molecules and therefore increases the frequency of collisions between the molecules.

- Activation energy, which is defined as the amount of energy required to make the reaction start and carry on spontaneously. Higher activation energy implies that the reactants need more energy to start than a reaction with a lower activation energy.

- Temperature, which hastens reactions if raised, since higher temperature increases the energy of the molecules, creating more collisions per unit time,

- The presence or absence of a catalyst. Catalysts are substances which change the pathway (mechanism) of a reaction which in turn increases the speed of a reaction by lowering the activation energy needed for the reaction to take place. A catalyst is not destroyed or changed during a reaction, so it can be used again.

- For some reactions, the presence of electromagnetic radiation, most notably ultraviolet light, is needed to promote the breaking of bonds to start the reaction. This is particularly true for reactions involving radicals.

Reaction types

Four basic types

Representation of four basic chemical reactions types: synthesis, decomposition, single replacement and double replacement.

Synthesis

In a synthesis reaction, two or more simple substances combine to form a more complex substance. These reactions are in the general form:Decomposition

A decomposition reaction is when a more complex substance breaks down into its more simple parts. It is thus the opposite of a synthesis reaction, and can be written as[18][19]Single replacement

In a single replacement reaction, a single uncombined element replaces another in a compound; in other words, one element trades places with another element in a compound[18] These reactions come in the general form of:Double replacement

In a double replacement reaction, the anions and cations of two compounds switch places and form two entirely different compounds.[18] These reactions are in the general form:[19]Another example of a double displacement reaction is the reaction of lead(II) nitrate with potassium iodide to form lead(II) iodide and potassium nitrate:

Oxidation and reduction

Illustration of a redox reaction

Sodium chloride is formed through the redox reaction of sodium metal and chlorine gas

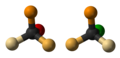

Redox reactions can be understood in terms of transfer of electrons from one involved species (reducing agent) to another (oxidizing agent). In this process, the former species is oxidized and the latter is reduced. Though sufficient for many purposes, these descriptions are not precisely correct. Oxidation is better defined as an increase in oxidation state, and reduction as a decrease in oxidation state. In practice, the transfer of electrons will always change the oxidation state, but there are many reactions that are classed as "redox" even though no electron transfer occurs (such as those involving covalent bonds).[20][21]

In the following redox reaction, hazardous sodium metal reacts with toxic chlorine gas to form the ionic compound sodium chloride, or common table salt:

Which of the involved reactants would be reducing or oxidizing agent can be predicted from the electronegativity of their elements. Elements with low electronegativity, such as most metals, easily donate electrons and oxidize – they are reducing agents. On the contrary, many ions with high oxidation numbers, such as H

2O

2, MnO−

4, CrO

3, Cr

2O2−

7, OsO

4 can gain one or two extra electrons and are strong oxidizing agents.

The number of electrons donated or accepted in a redox reaction can be predicted from the electron configuration of the reactant element. Elements try to reach the low-energy noble gas configuration, and therefore alkali metals and halogens will donate and accept one electron respectively. Noble gases themselves are chemically inactive.[22]

An important class of redox reactions are the electrochemical reactions, where electrons from the power supply are used as the reducing agent. These reactions are particularly important for the production of chemical elements, such as chlorine[23] or aluminium. The reverse process in which electrons are released in redox reactions and can be used as electrical energy is possible and used in batteries.

Complexation

In complexation reactions, several ligands react with a metal atom to form a coordination complex. This is achieved by providing lone pairs of the ligand into empty orbitals of the metal atom and forming dipolar bonds. The ligands are Lewis bases, they can be both ions and neutral molecules, such as carbon monoxide, ammonia or water. The number of ligands that react with a central metal atom can be found using the 18-electron rule, saying that the valence shells of a transition metal will collectively accommodate 18 electrons, whereas the symmetry of the resulting complex can be predicted with the crystal field theory and ligand field theory. Complexation reactions also include ligand exchange, in which one or more ligands are replaced by another, and redox processes which change the oxidation state of the central metal atom.[24]

Acid-base reactions

In the Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, an acid-base reaction involves a transfer of protons (H+) from one species (the acid) to another (the base). When a proton is removed from an acid, the resulting species is termed that acid's conjugate base. When the proton is accepted by a base, the resulting species is termed that base's conjugate acid.[25] In other words, acids act as proton donors and bases act as proton acceptors according to the following equation:Acid-base reactions can have different definitions depending on the acid-base concept employed. Some of the most common are:

- Arrhenius definition: Acids dissociate in water releasing H3O+ ions; bases dissociate in water releasing OH− ions.

- Brønsted-Lowry definition: Acids are proton (H+) donors, bases are proton acceptors; this includes the Arrhenius definition.

- Lewis definition: Acids are electron-pair acceptors, bases are electron-pair donors; this includes the Brønsted-Lowry definition.

Precipitation

Precipitation

Precipitation is the formation of a solid in a solution or inside another solid during a chemical reaction. It usually takes place when the concentration of dissolved ions exceeds the solubility limit[26] and forms an insoluble salt. This process can be assisted by adding a precipitating agent or by removal of the solvent. Rapid precipitation results in an amorphous or microcrystalline residue and slow process can yield single crystals. The latter can also be obtained by recrystallization from microcrystalline salts.[27]

Solid-state reactions

Reactions can take place between two solids. However, because of the relatively small diffusion rates in solids, the corresponding chemical reactions are very slow in comparison to liquid and gas phase reactions. They are accelerated by increasing the reaction temperature and finely dividing the reactant to increase the contacting surface area.[28]Reactions at the solid|gas interface

Reaction can take place at the solid|gas interface, surfaces at very low pressure such as ultra-high vacuum. Via scanning tunneling microscopy, it is possible to observe reactions at the solid|gas interface in real space, if the time scale of the reaction is in the correct range.[29][30] Reactions at the solid|gas interface are in some cases related to catalysis.Photochemical reactions

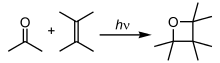

In this Paterno–Büchi reaction, a photoexcited carbonyl group is added to an unexcited olefin, yielding an oxetane.

In photochemical reactions, atoms and molecules absorb energy (photons) of the illumination light and convert into an excited state. They can then release this energy by breaking chemical bonds, thereby producing radicals. Photochemical reactions include hydrogen–oxygen reactions, radical polymerization, chain reactions and rearrangement reactions.[31]

Many important processes involve photochemistry. The premier example is photosynthesis, in which most plants use solar energy to convert carbon dioxide and water into glucose, disposing of oxygen as a side-product. Humans rely on photochemistry for the formation of vitamin D, and vision is initiated by a photochemical reaction of rhodopsin.[12] In fireflies, an enzyme in the abdomen catalyzes a reaction that results in bioluminescence.[32] Many significant photochemical reactions, such as ozone formation, occur in the Earth atmosphere and constitute atmospheric chemistry.

Catalysis

Schematic potential energy diagram showing the effect of a catalyst in

an endothermic chemical reaction. The presence of a catalyst opens a

different reaction pathway (in red) with a lower activation energy. The

final result and the overall thermodynamics are the same.

Solid heterogeneous catalysts are plated on meshes in ceramic catalytic converters in order to maximize their surface area. This exhaust converter is from a Peugeot 106 S2 1100

In catalysis, the reaction does not proceed directly, but through reaction with a third substance known as catalyst. Although the catalyst takes part in the reaction, it is returned to its original state by the end of the reaction and so is not consumed. However, it can be inhibited, deactivated or destroyed by secondary processes. Catalysts can be used in a different phase (heterogeneous) or in the same phase (homogeneous) as the reactants. In heterogeneous catalysis, typical secondary processes include coking where the catalyst becomes covered by polymeric side products. Additionally, heterogeneous catalysts can dissolve into the solution in a solid–liquid system or evaporate in a solid–gas system. Catalysts can only speed up the reaction – chemicals that slow down the reaction are called inhibitors.[33][34] Substances that increase the activity of catalysts are called promoters, and substances that deactivate catalysts are called catalytic poisons. With a catalyst, a reaction which is kinetically inhibited by a high activation energy can take place in circumvention of this activation energy.

Heterogeneous catalysts are usually solids, powdered in order to maximize their surface area. Of particular importance in heterogeneous catalysis are the platinum group metals and other transition metals, which are used in hydrogenations, catalytic reforming and in the synthesis of commodity chemicals such as nitric acid and ammonia. Acids are an example of a homogeneous catalyst, they increase the nucleophilicity of carbonyls, allowing a reaction that would not otherwise proceed with electrophiles. The advantage of homogeneous catalysts is the ease of mixing them with the reactants, but they may also be difficult to separate from the products. Therefore, heterogeneous catalysts are preferred in many industrial processes.[35]

Reactions in organic chemistry

In organic chemistry, in addition to oxidation, reduction or acid-base reactions, a number of other reactions can take place which involve covalent bonds between carbon atoms or carbon and heteroatoms (such as oxygen, nitrogen, halogens, etc.). Many specific reactions in organic chemistry are name reactions designated after their discoverers.Substitution

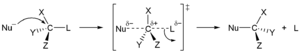

In a substitution reaction, a functional group in a particular chemical compound is replaced by another group.[36] These reactions can be distinguished by the type of substituting species into a nucleophilic, electrophilic or radical substitution.In the first type, a nucleophile, an atom or molecule with an excess of electrons and thus a negative charge or partial charge, replaces another atom or part of the "substrate" molecule. The electron pair from the nucleophile attacks the substrate forming a new bond, while the leaving group departs with an electron pair. The nucleophile may be electrically neutral or negatively charged, whereas the substrate is typically neutral or positively charged. Examples of nucleophiles are hydroxide ion, alkoxides, amines and halides. This type of reaction is found mainly in aliphatic hydrocarbons, and rarely in aromatic hydrocarbon. The latter have high electron density and enter nucleophilic aromatic substitution only with very strong electron withdrawing groups. Nucleophilic substitution can take place by two different mechanisms, SN1 and SN2. In their names, S stands for substitution, N for nucleophilic, and the number represents the kinetic order of the reaction, unimolecular or bimolecular.[37]

The three steps of an SN2 reaction. The nucleophile is green and the leaving group is red

The SN1 reaction proceeds in two steps. First, the leaving group is eliminated creating a carbocation. This is followed by a rapid reaction with the nucleophile.[38]

In the SN2 mechanism, the nucleophile forms a transition state with the attacked molecule, and only then the leaving group is cleaved. These two mechanisms differ in the stereochemistry of the products. SN1 leads to the non-stereospecific addition and does not result in a chiral center, but rather in a set of geometric isomers (cis/trans). In contrast, a reversal (Walden inversion) of the previously existing stereochemistry is observed in the SN2 mechanism.[39]

Electrophilic substitution is the counterpart of the nucleophilic substitution in that the attacking atom or molecule, an electrophile, has low electron density and thus a positive charge. Typical electrophiles are the carbon atom of carbonyl groups, carbocations or sulfur or nitronium cations. This reaction takes place almost exclusively in aromatic hydrocarbons, where it is called electrophilic aromatic substitution. The electrophile attack results in the so-called σ-complex, a transition state in which the aromatic system is abolished. Then, the leaving group, usually a proton, is split off and the aromaticity is restored. An alternative to aromatic substitution is electrophilic aliphatic substitution. It is similar to the nucleophilic aliphatic substitution and also has two major types, SE1 and SE2[40]

Mechanism of electrophilic aromatic substitution

In the third type of substitution reaction, radical substitution, the attacking particle is a radical.[36] This process usually takes the form of a chain reaction, for example in the reaction of alkanes with halogens. In the first step, light or heat disintegrates the halogen-containing molecules producing the radicals. Then the reaction proceeds as an avalanche until two radicals meet and recombine.[41]

-

- Reactions during the chain reaction of radical substitution

Addition and elimination

The addition and its counterpart, the elimination, are reactions which change the number of substitutents on the carbon atom, and form or cleave multiple bonds. Double and triple bonds can be produced by eliminating a suitable leaving group. Similar to the nucleophilic substitution, there are several possible reaction mechanisms which are named after the respective reaction order. In the E1 mechanism, the leaving group is ejected first, forming a carbocation. The next step, formation of the double bond, takes place with elimination of a proton (deprotonation). The leaving order is reversed in the E1cb mechanism, that is the proton is split off first. This mechanism requires participation of a base.[42] Because of the similar conditions, both reactions in the E1 or E1cb elimination always compete with the SN1 substitution.[43]

E2 elimination

The E2 mechanism also requires a base, but there the attack of the base and the elimination of the leaving group proceed simultaneously and produce no ionic intermediate. In contrast to the E1 eliminations, different stereochemical configurations are possible for the reaction product in the E2 mechanism, because the attack of the base preferentially occurs in the anti-position with respect to the leaving group. Because of the similar conditions and reagents, the E2 elimination is always in competition with the SN2-substitution.[44]

Electrophilic addition of hydrogen bromide

The counterpart of elimination is the addition where double or triple bonds are converted into single bonds. Similar to the substitution reactions, there are several types of additions distinguished by the type of the attacking particle. For example, in the electrophilic addition of hydrogen bromide, an electrophile (proton) attacks the double bond forming a carbocation, which then reacts with the nucleophile (bromine). The carbocation can be formed on either side of the double bond depending on the groups attached to its ends, and the preferred configuration can be predicted with the Markovnikov's rule.[45] This rule states that "In the heterolytic addition of a polar molecule to an alkene or alkyne, the more electronegative (nucleophilic) atom (or part) of the polar molecule becomes attached to the carbon atom bearing the smaller number of hydrogen atoms."[46]

If the addition of a functional group takes place at the less substituted carbon atom of the double bond, then the electrophilic substitution with acids is not possible. In this case, one has to use the hydroboration–oxidation reaction, where in the first step, the boron atom acts as electrophile and adds to the less substituted carbon atom. At the second step, the nucleophilic hydroperoxide or halogen anion attacks the boron atom.[47]

While the addition to the electron-rich alkenes and alkynes is mainly electrophilic, the nucleophilic addition plays an important role for the carbon-heteroatom multiple bonds, and especially its most important representative, the carbonyl group. This process is often associated with an elimination, so that after the reaction the carbonyl group is present again. It is therefore called addition-elimination reaction and may occur in carboxylic acid derivatives such as chlorides, esters or anhydrides. This reaction is often catalyzed by acids or bases, where the acids increase by the electrophilicity of the carbonyl group by binding to the oxygen atom, whereas the bases enhance the nucleophilicity of the attacking nucleophile.[48]

Acid-catalyzed addition-elimination mechanism

Nucleophilic addition of a carbanion or another nucleophile to the double bond of an alpha, beta unsaturated carbonyl compound can proceed via the Michael reaction, which belongs to the larger class of conjugate additions. This is one of the most useful methods for the mild formation of C–C bonds.[49][50][51]

Some additions which can not be executed with nucleophiles and electrophiles, can be succeeded with free radicals. As with the free-radical substitution, the radical addition proceeds as a chain reaction, and such reactions are the basis of the free-radical polymerization.[52]

Other organic reaction mechanisms

The Cope rearrangement of 3-methyl-1,5-hexadiene

In a rearrangement reaction, the carbon skeleton of a molecule is rearranged to give a structural isomer of the original molecule. These include hydride shift reactions such as the Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement, where a hydrogen, alkyl or aryl group migrates from one carbon to a neighboring carbon. Most rearrangements are associated with the breaking and formation of new carbon-carbon bonds. Other examples are sigmatropic reaction such as the Cope rearrangement.[53]

Cyclic rearrangements include cycloadditions and, more generally, pericyclic reactions, wherein two or more double bond-containing molecules form a cyclic molecule. An important example of cycloaddition reaction is the Diels–Alder reaction (the so-called [4+2] cycloaddition) between a conjugated diene and a substituted alkene to form a substituted cyclohexene system.[54]

Whether a certain cycloaddition would proceed depends on the electronic orbitals of the participating species, as only orbitals with the same sign of wave function will overlap and interact constructively to form new bonds. Cycloaddition is usually assisted by light or heat. These perturbations result in different arrangement of electrons in the excited state of the involved molecules and therefore in different effects. For example, the [4+2] Diels-Alder reactions can be assisted by heat whereas the [2+2] cycloaddition is selectively induced by light.[55] Because of the orbital character, the potential for developing stereoisomeric products upon cycloaddition is limited, as described by the Woodward–Hoffmann rules.[56]

Biochemical reactions

Illustration of the induced fit model of enzyme activity

Biochemical reactions are mainly controlled by enzymes. These proteins can specifically catalyze a single reaction, so that reactions can be controlled very precisely. The reaction takes place in the active site, a small part of the enzyme which is usually found in a cleft or pocket lined by amino acid residues, and the rest of the enzyme is used mainly for stabilization. The catalytic action of enzymes relies on several mechanisms including the molecular shape ("induced fit"), bond strain, proximity and orientation of molecules relative to the enzyme, proton donation or withdrawal (acid/base catalysis), electrostatic interactions and many others.[57]

The biochemical reactions that occur in living organisms are collectively known as metabolism. Among the most important of its mechanisms is the anabolism, in which different DNA and enzyme-controlled processes result in the production of large molecules such as proteins and carbohydrates from smaller units.[58] Bioenergetics studies the sources of energy for such reactions. An important energy source is glucose, which can be produced by plants via photosynthesis or assimilated from food. All organisms use this energy to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which can then be used to energize other reactions.

Applications

Thermite reaction proceeding in railway welding. Shortly after this, the liquid iron flows into the mould around the rail gap

Chemical reactions are central to chemical engineering where they are used for the synthesis of new compounds from natural raw materials such as petroleum and mineral ores. It is essential to make the reaction as efficient as possible, maximizing the yield and minimizing the amount of reagents, energy inputs and waste. Catalysts are especially helpful for reducing the energy required for the reaction and increasing its reaction rate.[59][60]

Some specific reactions have their niche applications. For example, the thermite reaction is used to generate light and heat in pyrotechnics and welding. Although it is less controllable than the more conventional oxy-fuel welding, arc welding and flash welding, it requires much less equipment and is still used to mend rails, especially in remote areas.[61]

![{\displaystyle v=-{\frac {d[{\ce {A}}]}{dt}}=k\cdot [{\ce {A}}].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/12291760fcaff20a02ff74abd0dfcb922664cddb)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {[A]}}(t)={\ce {[A]}}_{0}\cdot e^{-k\cdot t}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/498c37558508e2f7297604f93bb5408dcd8c3fd4)