Ultrasound representation of urinary bladder (black butterfly-like shape) a hyperplastic prostate. An example of practical science and medical science working together.

Example of an approximately 40,000 probe spotted oligo microarray with enlarged inset to show detail.

Biomedical engineering (BME) is the application of engineering principles and design concepts to medicine and biology for healthcare purposes (e.g. diagnostic or therapeutic). This field seeks to close the gap between engineering and medicine, combining the design and problem solving skills of engineering with medical biological sciences to advance health care treatment, including diagnosis, monitoring, and therapy.[1] Biomedical engineering has only recently emerged as its own study, as compared to many other engineering fields. Such an evolution is common as a new field transitions from being an interdisciplinary specialization among already-established fields, to being considered a field in itself. Much of the work in biomedical engineering consists of research and development, spanning a broad array of subfields (see below). Prominent biomedical engineering applications include the development of biocompatible prostheses, various diagnostic and therapeutic medical devices ranging from clinical equipment to micro-implants, common imaging equipment such as MRIs and EKG/ECGs, regenerative tissue growth, pharmaceutical drugs and therapeutic biologicals.

Bioinformatics

Bioinformatics is an interdisciplinary field that develops methods and software tools for understanding biological data. As an interdisciplinary field of science, bioinformatics combines computer science, statistics, mathematics, and engineering to analyze and interpret biological data.Bioinformatics is both an umbrella term for the body of biological studies that use computer programming as part of their methodology, as well as a reference to specific analysis "pipelines" that are repeatedly used, particularly in the field of genomics. Common uses of bioinformatics include the identification of candidate genes and nucleotides (SNPs). Often, such identification is made with the aim of better understanding the genetic basis of disease, unique adaptations, desirable properties (esp. in agricultural species), or differences between populations. In a less formal way, bioinformatics also tries to understand the organisational principles within nucleic acid and protein sequences.

Biomechanics

Biomechanics is the study of the structure and function of the mechanical aspects of biological systems, at any level from whole organisms to organs, cells and cell organelles,[2] using the methods of mechanics.[3]Biomaterial

A biomaterial is any matter, surface, or construct that interacts with living systems. As a science, biomaterials is about fifty years old. The study of biomaterials is called biomaterials science or biomaterials engineering. It has experienced steady and strong growth over its history, with many companies investing large amounts of money into the development of new products. Biomaterials science encompasses elements of medicine, biology, chemistry, tissue engineering and materials science.Biomedical optics

Biomedical optics refers to the interaction of biological tissue and light, and how this can be exploited for sensing, imaging, and treatment.[4]Tissue engineering

Tissue engineering, like genetic engineering (see below), is a major segment of biotechnology – which overlaps significantly with BME.One of the goals of tissue engineering is to create artificial organs (via biological material) for patients that need organ transplants. Biomedical engineers are currently researching methods of creating such organs. Researchers have grown solid jawbones[5] and tracheas[6] from human stem cells towards this end. Several artificial urinary bladders have been grown in laboratories and transplanted successfully into human patients.[7] Bioartificial organs, which use both synthetic and biological component, are also a focus area in research, such as with hepatic assist devices that use liver cells within an artificial bioreactor construct.[8]

Micromass cultures of C3H-10T1/2 cells at varied oxygen tensions stained with Alcian blue.

Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, recombinant DNA technology, genetic modification/manipulation (GM) and gene splicing are terms that apply to the direct manipulation of an organism's genes. Unlike traditional breeding, an indirect method of genetic manipulation, genetic engineering utilizes modern tools such as molecular cloning and transformation to directly alter the structure and characteristics of target genes. Genetic engineering techniques have found success in numerous applications. Some examples include the improvement of crop technology (not a medical application, but see biological systems engineering), the manufacture of synthetic human insulin through the use of modified bacteria, the manufacture of erythropoietin in hamster ovary cells, and the production of new types of experimental mice such as the oncomouse (cancer mouse) for research.Neural engineering

Neural engineering (also known as neuroengineering) is a discipline that uses engineering techniques to understand, repair, replace, or enhance neural systems. Neural engineers are uniquely qualified to solve design problems at the interface of living neural tissue and non-living constructs.Pharmaceutical engineering

Pharmaceutical engineering is an interdisciplinary science that includes drug engineering, novel drug delivery and targeting, pharmaceutical technology, unit operations of Chemical Engineering, and Pharmaceutical Analysis. It may be deemed as a part of pharmacy due to its focus on the use of technology on chemical agents in providing better medicinal treatment. The ISPE is an international body that certifies this now rapidly emerging interdisciplinary science.Medical devices

This is an extremely broad category—essentially covering all health care products that do not achieve their intended results through predominantly chemical (e.g., pharmaceuticals) or biological (e.g., vaccines) means, and do not involve metabolism.A medical device is intended for use in:

- the diagnosis of disease or other conditions, or

- in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease.

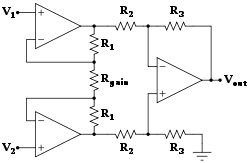

Biomedical instrumentation amplifier schematic used in monitoring low voltage biological signals, an example of a biomedical engineering application of electronic engineering to electrophysiology.

Stereolithography is a practical example of medical modeling being used to create physical objects. Beyond modeling organs and the human body, emerging engineering techniques are also currently used in the research and development of new devices for innovative therapies,[9] treatments,[10] patient monitoring,[11] of complex diseases.

Medical devices are regulated and classified (in the US) as follows (see also Regulation):

- Class I devices present minimal potential for harm to the user and are often simpler in design than Class II or Class III devices. Devices in this category include tongue depressors, bedpans, elastic bandages, examination gloves, and hand-held surgical instruments and other similar types of common equipment.

- Class II devices are subject to special controls in addition to the general controls of Class I devices. Special controls may include special labeling requirements, mandatory performance standards, and postmarket surveillance. Devices in this class are typically non-invasive and include X-ray machines, PACS, powered wheelchairs, infusion pumps, and surgical drapes.

- Class III devices generally require premarket approval (PMA) or premarket notification (510k), a scientific review to ensure the device's safety and effectiveness, in addition to the general controls of Class I. Examples include replacement heart valves, hip and knee joint implants, silicone gel-filled breast implants, implanted cerebellar stimulators, implantable pacemaker pulse generators and endosseous (intra-bone) implants.

Medical imaging

Medical/biomedical imaging is a major segment of medical devices. This area deals with enabling clinicians to directly or indirectly "view" things not visible in plain sight (such as due to their size, and/or location). This can involve utilizing ultrasound, magnetism, UV, radiology, and other means.

An MRI scan of a human head, an example of a biomedical engineering application of electrical engineering to diagnostic imaging.

Imaging technologies are often essential to medical diagnosis, and are typically the most complex equipment found in a hospital including: fluoroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), nuclear medicine, positron emission tomography (PET), PET-CT scans, projection radiography such as X-rays and CT scans, tomography, ultrasound, optical microscopy, and electron microscopy.

Implants

An implant is a kind of medical device made to replace and act as a missing biological structure (as compared with a transplant, which indicates transplanted biomedical tissue). The surface of implants that contact the body might be made of a biomedical material such as titanium, silicone or apatite depending on what is the most functional. In some cases, implants contain electronics, e.g. artificial pacemakers and cochlear implants. Some implants are bioactive, such as subcutaneous drug delivery devices in the form of implantable pills or drug-eluting stents.

Artificial limbs: The right arm is an example of a prosthesis, and the left arm is an example of myoelectric control.

A prosthetic eye, an example of a biomedical engineering application of mechanical engineering and biocompatible materials to ophthalmology.

Bionics

Artificial body part replacements are one of the many applications of bionics. Concerned with the intricate and thorough study of the properties and function of human body systems, bionics may be applied to solve some engineering problems. Careful study of the different functions and processes of the eyes, ears, and other organs paved the way for improved cameras, television, radio transmitters and receivers, and many other useful tools. These developments have indeed made our lives better, but the best contribution that bionics has made is in the field of biomedical engineering (the building of useful replacements for various parts of the human body). Modern hospitals now have available spare parts to replace body parts badly damaged by injury or disease [Citation Needed]. Biomedical engineers work hand in hand with doctors to build these artificial body parts.Clinical engineering

Clinical engineering is the branch of biomedical engineering dealing with the actual implementation of medical equipment and technologies in hospitals or other clinical settings. Major roles of clinical engineers include training and supervising biomedical equipment technicians (BMETs), selecting technological products/services and logistically managing their implementation, working with governmental regulators on inspections/audits, and serving as technological consultants for other hospital staff (e.g. physicians, administrators, I.T., etc.). Clinical engineers also advise and collaborate with medical device producers regarding prospective design improvements based on clinical experiences, as well as monitor the progression of the state of the art so as to redirect procurement patterns accordingly.Their inherent focus on practical implementation of technology has tended to keep them oriented more towards incremental-level redesigns and reconfigurations, as opposed to revolutionary research & development or ideas that would be many years from clinical adoption; however, there is a growing effort to expand this time-horizon over which clinical engineers can influence the trajectory of biomedical innovation. In their various roles, they form a "bridge" between the primary designers and the end-users, by combining the perspectives of being both 1) close to the point-of-use, while 2) trained in product and process engineering. Clinical engineering departments will sometimes hire not just biomedical engineers, but also industrial/systems engineers to help address operations research/optimization, human factors, cost analysis, etc. Also see safety engineering for a discussion of the procedures used to design safe systems.

Rehabilitation engineering

Rehabilitation engineering is the systematic application of engineering sciences to design, develop, adapt, test, evaluate, apply, and distribute technological solutions to problems confronted by individuals with disabilities. Functional areas addressed through rehabilitation engineering may include mobility, communications, hearing, vision, and cognition, and activities associated with employment, independent living, education, and integration into the community.[1]While some rehabilitation engineers have master's degrees in rehabilitation engineering, usually a subspecialty of Biomedical engineering, most rehabilitation engineers have undergraduate or graduate degrees in biomedical engineering, mechanical engineering, or electrical engineering. A Portuguese university provides an undergraduate degree and a master's degree in Rehabilitation Engineering and Accessibility.[5][7] Qualification to become a Rehab' Engineer in the UK is possible via a University BSc Honours Degree course such as Health Design & Technology Institute, Coventry University.[8]

The rehabilitation process for people with disabilities often entails the design of assistive devices such as Walking aids intended to promote inclusion of their users into the mainstream of society, commerce, and recreation.

Schematic representation of a normal ECG trace showing sinus rhythm; an example of widely used clinical medical equipment (operates by applying electronic engineering to electrophysiology and medical diagnosis).

Regulatory issues

Regulatory issues have been constantly increased in the last decades to respond to the many incidents caused by devices to patients. For example, from 2008 to 2011, in US, there were 119 FDA recalls of medical devices classified as class I. According to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Class I recall is associated to "a situation in which there is a reasonable probability that the use of, or exposure to, a product will cause serious adverse health consequences or death"[12]Regardless of the country-specific legislation, the main regulatory objectives coincide worldwide.[13] For example, in the medical device regulations, a product must be: 1) safe and 2) effective and 3) for all the manufactured devices

A product is safe if patients, users and third parties do not run unacceptable risks of physical hazards (death, injuries, …) in its intended use. Protective measures have to be introduced on the devices to reduce residual risks at acceptable level if compared with the benefit derived from the use of it.

A product is effective if it performs as specified by the manufacturer in the intended use. Effectiveness is achieved through clinical evaluation, compliance to performance standards or demonstrations of substantial equivalence with an already marketed device.

The previous features have to be ensured for all the manufactured items of the medical device. This requires that a quality system shall be in place for all the relevant entities and processes that may impact safety and effectiveness over the whole medical device lifecycle.

The medical device engineering area is among the most heavily regulated fields of engineering, and practicing biomedical engineers must routinely consult and cooperate with regulatory law attorneys and other experts. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the principal healthcare regulatory authority in the United States, having jurisdiction over medical devices, drugs, biologics, and combination products. The paramount objectives driving policy decisions by the FDA are safety and effectiveness of healthcare products that have to be assured through a quality system in place as specified under 21 CFR 829 regulation. In addition, because biomedical engineers often develop devices and technologies for "consumer" use, such as physical therapy devices (which are also "medical" devices), these may also be governed in some respects by the Consumer Product Safety Commission. The greatest hurdles tend to be 510K "clearance" (typically for Class 2 devices) or pre-market "approval" (typically for drugs and class 3 devices).

In the European context, safety effectiveness and quality is ensured through the "Conformity Assessment" that is defined as "the method by which a manufacturer demonstrates that its device complies with the requirements of the European Medical Device Directive". The directive specifies different procedures according to the class of the device ranging from the simple Declaration of Conformity (Annex VII) for Class I devices to EC verification (Annex IV), Production quality assurance (Annex V), Product quality assurance (Annex VI) and Full quality assurance (Annex II). The Medical Device Directive specifies detailed procedures for Certification. In general terms, these procedures include tests and verifications that are to be contained in specific deliveries such as the risk management file, the technical file and the quality system deliveries. The risk management file is the first deliverable that conditions the following design and manufacturing steps. Risk management stage shall drive the product so that product risks are reduced at an acceptable level with respect to the benefits expected for the patients for the use of the device. The technical file contains all the documentation data and records supporting medical device certification. FDA technical file has similar content although organized in different structure. The Quality System deliverables usually includes procedures that ensure quality throughout all product life cycle. The same standard (ISO EN 13485) is usually applied for quality management systems in US and worldwide.

Implants, such as artificial hip joints, are generally extensively regulated due to the invasive nature of such devices.

In the European Union, there are certifying entities named "Notified Bodies", accredited by European Member States. The Notified Bodies must ensure the effectiveness of the certification process for all medical devices apart from the class I devices where a declaration of conformity produced by the manufacturer is sufficient for marketing. Once a product has passed all the steps required by the Medical Device Directive, the device is entitled to bear a CE marking, indicating that the device is believed to be safe and effective when used as intended, and, therefore, it can be marketed within the European Union area.

The different regulatory arrangements sometimes result in particular technologies being developed first for either the U.S. or in Europe depending on the more favorable form of regulation. While nations often strive for substantive harmony to facilitate cross-national distribution, philosophical differences about the optimal extent of regulation can be a hindrance; more restrictive regulations seem appealing on an intuitive level, but critics decry the tradeoff cost in terms of slowing access to life-saving developments.

RoHS II

Directive 2011/65/EU, better known as RoHS 2 is a recast of legislation originally introduced in 2002. The original EU legislation "Restrictions of Certain Hazardous Substances in Electrical and Electronics Devices" (RoHS Directive 2002/95/EC) was replaced and superseded by 2011/65/EU published in July 2011 and commonly known as RoHS 2. RoHS seeks to limit the dangerous substances in circulation in electronics products, in particular toxins and heavy metals, which are subsequently released into the environment when such devices are recycled.The scope of RoHS 2 is widened to include products previously excluded, such as medical devices and industrial equipment. In addition, manufacturers are now obliged to provide conformity risk assessments and test reports – or explain why they are lacking. For the first time, not only manufacturers, but also importers and distributors share a responsibility to ensure Electrical and Electronic Equipment within the scope of RoHS comply with the hazardous substances limits and have a CE mark on their products.

IEC 60601

The new International Standard IEC 60601 for home healthcare electro-medical devices defining the requirements for devices used in the home healthcare environment. IEC 60601-1-11 (2010) must now be incorporated into the design and verification of a wide range of home use and point of care medical devices along with other applicable standards in the IEC 60601 3rd edition series.The mandatory date for implementation of the EN European version of the standard is June 1, 2013. The US FDA requires the use of the standard on June 30, 2013, while Health Canada recently extended the required date from June 2012 to April 2013. The North American agencies will only require these standards for new device submissions, while the EU will take the more severe approach of requiring all applicable devices being placed on the market to consider the home healthcare standard.

AS/NZS 3551:2012

AS/ANS 3551:2012 is the Australian and New Zealand standards for the management of medical devices. The standard specifies the procedures required to maintain a wide range of medical assets in a clinical setting (e.g. Hospital).[14] The standards are based on the IEC 606101 standards.The standard covers a wide range of medical equipment management elements including, procurement, acceptance testing, maintenance (electrical safety and preventative maintenance testing) and decommissioning.

Training and certification

Education

Biomedical engineers require considerable knowledge of both engineering and biology, and typically have a Bachelor's (B.Tech, B.S) or Master's (M.S., M.Tech, M.S.E., or M.Eng.) or a Doctoral (Ph.D.) degree in BME (Biomedical Engineering) or another branch of engineering with considerable potential for BME overlap. As interest in BME increases, many engineering colleges now have a Biomedical Engineering Department or Program, with offerings ranging from the undergraduate (B.Tech, B.S., B.Eng or B.S.E.) to doctoral levels. Biomedical engineering has only recently been emerging as its own discipline rather than a cross-disciplinary hybrid specialization of other disciplines; and BME programs at all levels are becoming more widespread, including the Bachelor of Science in Biomedical Engineering which actually includes so much biological science content that many students use it as a "pre-med" major in preparation for medical school. The number of biomedical engineers is expected to rise as both a cause and effect of improvements in medical technology.[15]In the U.S., an increasing number of undergraduate programs are also becoming recognized by ABET as accredited bioengineering/biomedical engineering programs. Over 65 programs are currently accredited by ABET.[16][17]

In Canada and Australia, accredited graduate programs in Biomedical Engineering are common, for example in Universities such as McMaster University, and the first Canadian undergraduate BME program at Ryerson University offering a four-year B.Eng program.[18][19][20][21] The Polytechnique in Montreal is also offering a bachelors's degree in biomedical engineering.

As with many degrees, the reputation and ranking of a program may factor into the desirability of a degree holder for either employment or graduate admission. The reputation of many undergraduate degrees are also linked to the institution's graduate or research programs, which have some tangible factors for rating, such as research funding and volume, publications and citations. With BME specifically, the ranking of a university's hospital and medical school can also be a significant factor in the perceived prestige of its BME department/program.

Graduate education is a particularly important aspect in BME. While many engineering fields (such as mechanical or electrical engineering) do not need graduate-level training to obtain an entry-level job in their field, the majority of BME positions do prefer or even require them.[22] Since most BME-related professions involve scientific research, such as in pharmaceutical and medical device development, graduate education is almost a requirement (as undergraduate degrees typically do not involve sufficient research training and experience). This can be either a Masters or Doctoral level degree; while in certain specialties a Ph.D. is notably more common than in others, it is hardly ever the majority (except in academia). In fact, the perceived need for some kind of graduate credential is so strong that some undergraduate BME programs will actively discourage students from majoring in BME without an expressed intention to also obtain a master's degree or apply to medical school afterwards.

Graduate programs in BME, like in other scientific fields, are highly varied, and particular programs may emphasize certain aspects within the field. They may also feature extensive collaborative efforts with programs in other fields (such as the University's Medical School or other engineering divisions), owing again to the interdisciplinary nature of BME. M.S. and Ph.D. programs will typically require applicants to have an undergraduate degree in BME, or another engineering discipline (plus certain life science coursework), or life science (plus certain engineering coursework).

Education in BME also varies greatly around the world. By virtue of its extensive biotechnology sector, its numerous major universities, and relatively few internal barriers, the U.S. has progressed a great deal in its development of BME education and training opportunities. Europe, which also has a large biotechnology sector and an impressive education system, has encountered trouble in creating uniform standards as the European community attempts to supplant some of the national jurisdictional barriers that still exist. Recently, initiatives such as BIOMEDEA have sprung up to develop BME-related education and professional standards.[23] Other countries, such as Australia, are recognizing and moving to correct deficiencies in their BME education.[24] Also, as high technology endeavors are usually marks of developed nations, some areas of the world are prone to slower development in education, including in BME.

Licensure/certification

As with other learned professions, each state has certain (fairly similar) requirements for becoming licensed as a registered Professional Engineer (PE), but, in US, in industry such a license is not required to be an employee as an engineer in the majority of situations (due to an exception known as the industrial exemption, which effectively applies to the vast majority of American engineers). The US model has generally been only to require the practicing engineers offering engineering services that impact the public welfare, safety, safeguarding of life, health, or property to be licensed, while engineers working in private industry without a direct offering of engineering services to the public or other businesses, education, and government need not be licensed. This is notably not the case in many other countries, where a license is as legally necessary to practice engineering as it is for law or medicine.Biomedical engineering is regulated in some countries, such as Australia, but registration is typically only recommended and not required.[25]

In the UK, mechanical engineers working in the areas of Medical Engineering, Bioengineering or Biomedical engineering can gain Chartered Engineer status through the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. The Institution also runs the Engineering in Medicine and Health Division.[26] The Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine (IPEM) has a panel for the accreditation of MSc courses in Biomedical Engineering and Chartered Engineering status can also be sought through IPEM.

The Fundamentals of Engineering exam – the first (and more general) of two licensure examinations for most U.S. jurisdictions—does now cover biology (although technically not BME). For the second exam, called the Principles and Practices, Part 2, or the Professional Engineering exam, candidates may select a particular engineering discipline's content to be tested on; there is currently not an option for BME with this, meaning that any biomedical engineers seeking a license must prepare to take this examination in another category (which does not affect the actual license, since most jurisdictions do not recognize discipline specialties anyway). However, the Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) is, as of 2009, exploring the possibility of seeking to implement a BME-specific version of this exam to facilitate biomedical engineers pursuing licensure.

Beyond governmental registration, certain private-sector professional/industrial organizations also offer certifications with varying degrees of prominence. One such example is the Certified Clinical Engineer (CCE) certification for Clinical engineers.

Career prospects

In 2012 there were about 19,400 biomedical engineers employed in the US, and the field was predicted to grow by 27% (much faster than average) from 2012 to 2022.[27] Biomedical engineering has the highest percentage of women engineers compared to other common engineering professions.Notable figures

- Forrest Bird (deceased) – aviator and pioneer in the invention of mechanical ventilators

- Y.C. Fung – professor emeritus at the University of California, San Diego, considered by many to be the founder of modern biomechanics[28]

- Leslie Geddes (deceased) – professor emeritus at Purdue University, electrical engineer, inventor, and educator of over 2000 biomedical engineers, received a National Medal of Technology in 2006 from President George Bush[29] for his more than 50 years of contributions that have spawned innovations ranging from burn treatments to miniature defibrillators, ligament repair to tiny blood pressure monitors for premature infants, as well as a new method for performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

- Willem Johan Kolff (deceased) – pioneer of hemodialysis as well as in the field of artificial organs

- Robert Langer – Institute Professor at MIT, runs the largest BME laboratory in the world, pioneer in drug delivery and tissue engineering[30]

- John Macleod (deceased) – one of the co-discoverers of insulin at Case Western Reserve University.

- Alfred E. Mann – Physicist, entrepreneur and philanthropist. A pioneer in the field of Biomedical Engineering.[31]

- Nicholas A. Peppas – Chaired Professor in Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, pioneer in drug delivery, biomaterials, hydrogels and nanobiotechnology.

- Robert Plonsey – professor emeritus at Duke University, pioneer of electrophysiology[32]

- Robert M. Nerem – professor emeritus at Georgia Institute of Technology. Pioneer in regenerative tissue, biomechanics, and author of over 300 published works. His works have been cited more than 20,000 times cumulatively.

- Otto Schmitt (deceased) – biophysicist with significant contributions to BME, working with biomimetics

- Ascher Shapiro (deceased) – Institute Professor at MIT, contributed to the development of the BME field, medical devices (e.g. intra-aortic balloons)

- John G. Webster – professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, a pioneer in the field of instrumentation amplifiers for the recording of electrophysiological signals

- U.A. Whitaker (deceased) – provider of the Whitaker Foundation, which supported research and education in BME by providing over $700 million to various universities, helping to create 30 BME programs and helping finance the construction of 13 buildings[33]