| |

| Author | Samuel P. Huntington |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Simon & Schuster |

Publication date

| 1997 |

| ISBN | 978-0-684-84441-1 |

| OCLC | 38269418 |

The Clash of Civilizations is a hypothesis that people's cultural and religious identities will be the primary source of conflict in the post-Cold War world. The American political scientist Samuel P. Huntington argued that future wars would be fought not between countries, but between cultures, and that Islamic extremism would become the biggest threat to world peace. It was proposed in a 1992 lecture at the American Enterprise Institute, which was then developed in a 1993 Foreign Affairs article titled "The Clash of Civilizations?", in response to his former student Francis Fukuyama's 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man. Huntington later expanded his thesis in a 1996 book The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order.

The phrase itself was earlier used by Albert Camus in 1946, by Girilal Jain in his analysis of the Ayodhya dispute in 1988, by Bernard Lewis in an article in the September 1990 issue of The Atlantic Monthly titled "The Roots of Muslim Rage" and by Mahdi El Mandjra in his book "La première guerre civilisationnelle" published in 1992. Even earlier, the phrase appears in a 1926 book regarding the Middle East by Basil Mathews: Young Islam on Trek: A Study in the Clash of Civilizations (p. 196). This expression derives from "clash of cultures", already used during the colonial period and the Belle Époque.

Huntington began his thinking by surveying the diverse theories about the nature of global politics in the post-Cold War period. Some theorists and writers argued that human rights, liberal democracy, and the capitalist free market economy had become the only remaining ideological alternative for nations in the post-Cold War world. Specifically, Francis Fukuyama argued that the world had reached the 'end of history' in a Hegelian sense.

Huntington believed that while the age of ideology had ended, the world had only reverted to a normal state of affairs characterized by cultural conflict. In his thesis, he argued that the primary axis of conflict in the future will be along cultural lines. As an extension, he posits that the concept of different civilizations, as the highest rank of cultural identity, will become increasingly useful in analyzing the potential for conflict. At the end of his 1993 Foreign Affairs article, "The Clash of Civilizations?", Huntington writes, "This is not to advocate the desirability of conflicts between civilizations. It is to set forth descriptive hypothesis as to what the future may be like."

In addition, the clash of civilizations, for Huntington, represents a development of history. In the past, world history was mainly about the struggles between monarchs, nations and ideologies, such as seen within Western civilization. But after the end of the Cold War, world politics moved into a new phase, in which non-Western civilizations are no longer the exploited recipients of Western civilization but have become additional important actors joining the West to shape and move world history.

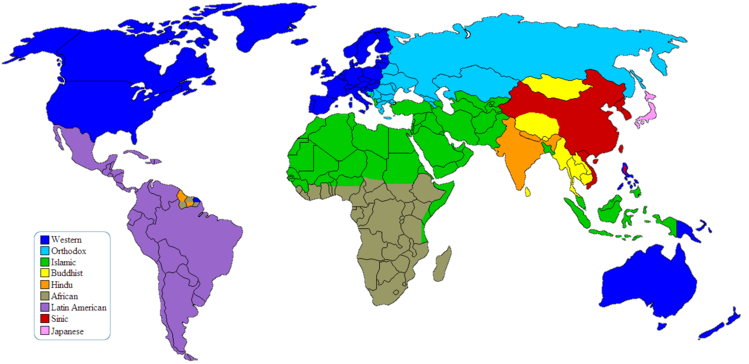

Major civilizations according to Huntington

The clash of civilizations according to Huntington (1996),

as presented in the book. Huntington divided the world into

the "major civilizations" in his thesis as such:

- Western civilization, comprising the United States and Canada, Western and Central Europe, Australia and Oceania. Whether Latin America and the former member states of the Soviet Union are included, or are instead their own separate civilizations, will be an important future consideration for those regions, according to Huntington. The traditional Western viewpoint identified Western Civilization with the Western Christian (Catholic-Protestant) countries and culture.

- Latin American. Includes Central America, South America (excluding Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana), Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico. May be considered a part of Western civilization. Many people in South America and Mexico regard themselves as full members of Western civilization (especially White Latin Americans).

- The Orthodox world of the former Soviet Union, the former Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece and Romania.

- Countries with a non-Orthodox majority are usually excluded e.g. Muslim Azerbaijan and Muslim Albania and most of Central Asia, as well as majority Muslim regions in the Balkans, Caucasus and central Russian regions such as Tatarstan and Bashkortostan, Roman Catholic Slovenia and Croatia, Protestant and Catholic Baltic states). However, Armenia is included, despite its dominant faith, the Armenian Apostolic Church, being a part of Oriental Orthodoxy rather than the Eastern Orthodox Church, and Kazakhstan is also included, despite its dominant faith being Sunni Islam.

- The Eastern world is the mix of the Buddhist, Chinese, Hindu, and Japonic civilizations.

- The Buddhist areas of Bhutan, Cambodia, Laos, Mongolia, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Thailand are identified as separate from other civilizations, but Huntington believes that they do not constitute a major civilization in the sense of international affairs.

- The Confucian civilization of China, the Koreas, Singapore, Taiwan, and Vietnam. This group also includes the Chinese diaspora, especially in relation to Southeast Asia.

- Hindu civilization, located chiefly in India, Bhutan and Nepal, and culturally adhered to by the global Indian diaspora.

- Japan, considered a hybrid of Chinese civilization and older Altaic patterns.

- The Muslim world of the Greater Middle East (excluding Armenia, Cyprus, Ethiopia, Georgia, Israel, Malta and South Sudan), northern West Africa, Albania, Bangladesh, parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brunei, Comoros, Indonesia, Malaysia and Maldives.

- The civilization of Sub-Saharan Africa located in Southern Africa, Middle Africa (excluding Chad), East Africa (excluding Ethiopia, the Comoros, Mauritius, and the Swahili coast of Kenya and Tanzania), Cape Verde, Ghana, the Ivory Coast, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Considered as a possible 8th civilization by Huntington.

- Instead of belonging to one of the "major" civilizations, Ethiopia and Haiti are labeled as "Lone" countries. Israel could be considered a unique state with its own civilization, Huntington writes, but one which is extremely similar to the West. Huntington also believes that the Anglophone Caribbean, former British colonies in the Caribbean, constitutes a distinct entity.

- There are also others which are considered "cleft countries" because they contain very large groups of people identifying with separate civilizations. Examples include Ukraine ("cleft" between its Eastern Rite Catholic-dominated western section and its Orthodox-dominated east), French Guiana (cleft between Latin America, and the West), Benin, Chad, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Togo (all cleft between Islam and Sub-Saharan Africa), Guyana and Suriname (cleft between Hindu and Sub-Saharan African), Sri Lanka (cleft between Hindu and Buddhist), China (cleft between Sinic and Buddhist, in the case of Tibet; and the West, in the case of Hong Kong and Macau), and the Philippines (cleft between Islam, in the case of Mindanao; Sinic, and the West). Sudan was also included as "cleft" between Islam and Sub-Saharan Africa; this division became a formal split in July 2011 following an overwhelming vote for independence by South Sudan in a January 2011 referendum.

Huntington's thesis of civilizational clash

Huntington at the 2004 World Economic Forum

Huntington argues that the trends of global conflict after the end of the Cold War are increasingly appearing at these civilizational divisions. Wars such as those following the break up of Yugoslavia, in Chechnya, and between India and Pakistan were cited as evidence of inter-civilizational conflict. He also argues that the widespread Western belief in the universality of the West's values and political systems is naïve and that continued insistence on democratization and such "universal" norms will only further antagonize other civilizations. Huntington sees the West as reluctant to accept this because it built the international system, wrote its laws, and gave it substance in the form of the United Nations.

Huntington identifies a major shift of economic, military, and political power from the West to the other civilizations of the world, most significantly to what he identifies as the two "challenger civilizations", Sinic and Islam.

In Huntington's view, East Asian Sinic civilization is culturally asserting itself and its values relative to the West due to its rapid economic growth. Specifically, he believes that China's goals are to reassert itself as the regional hegemon, and that other countries in the region will 'bandwagon' with China due to the history of hierarchical command structures implicit in the Confucian Sinic civilization, as opposed to the individualism and pluralism valued in the West. Regional powers such as the two Koreas and Vietnam will acquiesce to Chinese demands and become more supportive of China rather than attempting to oppose it. Huntington therefore believes that the rise of China poses one of the most significant problems and the most powerful long-term threat to the West, as Chinese cultural assertion clashes with the American desire for the lack of a regional hegemony in East Asia.

Huntington argues that the Islamic civilization has experienced a massive population explosion which is fueling instability both on the borders of Islam and in its interior, where fundamentalist movements are becoming increasingly popular. Manifestations of what he terms the "Islamic Resurgence" include the 1979 Iranian revolution and the first Gulf War. Perhaps the most controversial statement Huntington made in the Foreign Affairs article was that "Islam has bloody borders". Huntington believes this to be a real consequence of several factors, including the previously mentioned Muslim youth bulge and population growth and Islamic proximity to many civilizations including Sinic, Orthodox, Western, and African.

Huntington sees Islamic civilization as a potential ally to China, both having more revisionist goals and sharing common conflicts with other civilizations, especially the West. Specifically, he identifies common Chinese and Islamic interests in the areas of weapons proliferation, human rights, and democracy that conflict with those of the West, and feels that these are areas in which the two civilizations will cooperate.

Russia, Japan, and India are what Huntington terms 'swing civilizations' and may favor either side. Russia, for example, clashes with the many Muslim ethnic groups on its southern border (such as Chechnya) but—according to Huntington—cooperates with Iran to avoid further Muslim-Orthodox violence in Southern Russia, and to help continue the flow of oil. Huntington argues that a "Sino-Islamic connection" is emerging in which China will cooperate more closely with Iran, Pakistan, and other states to augment its international position.

Huntington also argues that civilizational conflicts are "particularly prevalent between Muslims and non-Muslims", identifying the "bloody borders" between Islamic and non-Islamic civilizations. This conflict dates back as far as the initial thrust of Islam into Europe, its eventual expulsion in the Iberian reconquest, the attacks of the Ottoman Turks on Eastern Europe and Vienna, and the European imperial division of the Islamic nations in the 1800s and 1900s.

Huntington also believes that some of the factors contributing to this conflict are that both Christianity (upon which Western civilization is based) and Islam are:

- Missionary religions, seeking conversion of others

- Universal, "all-or-nothing" religions, in the sense that it is believed by both sides that only their faith is the correct one

- Teleological religions, that is, that their values and beliefs represent the goals of existence and purpose in human existence.

Why civilizations will clash

Huntington offers six explanations for why civilizations will clash:- Differences among civilizations are too basic in that civilizations are differentiated from each other by history, language, culture, tradition, and, most importantly, religion. These fundamental differences are the product of centuries and the foundations of different civilizations, meaning they will not be gone soon.

- The world is becoming a smaller place. As a result, interactions across the world are increasing, which intensify "civilization consciousness" and the awareness of differences between civilizations and commonalities within civilizations.

- Due to economic modernization and social change, people are separated from longstanding local identities. Instead, religion has replaced this gap, which provides a basis for identity and commitment that transcends national boundaries and unites civilizations.

- The growth of civilization-consciousness is enhanced by the dual role of the West. On the one hand, the West is at a peak of power. At the same time, a return-to-the-roots phenomenon is occurring among non-Western civilizations. A West at the peak of its power confronts non-Western countries that increasingly have the desire, the will and the resources to shape the world in non-Western ways.

- Cultural characteristics and differences are less mutable and hence less easily compromised and resolved than political and economic ones.

- Economic regionalism is increasing. Successful economic regionalism will reinforce civilization-consciousness. Economic regionalism may succeed only when it is rooted in a common civilization.

The West versus the Rest

Huntington suggests that in the future the central axis of world politics tends to be the conflict between Western and non-Western civilizations, in [Stuart Hall]'s phrase, the conflict between "the West and the Rest". He offers three forms of general actions that non-Western civilization can take in response to Western countries.- Non-Western countries can attempt to achieve isolation in order to preserve their own values and protect themselves from Western invasion. However, Huntington argues that the costs of this action are high and only a few states can pursue it.

- According to the theory of "band-wagoning" non-Western countries can join and accept Western values.

- Non-Western countries can make an effort to balance Western power through modernization. They can develop economic, military power and cooperate with other non-Western countries against the West while still preserving their own values and institutions. Huntington believes that the increasing power of non-Western civilizations in international society will make the West begin to develop a better understanding of the cultural fundamentals underlying other civilizations. Therefore, Western civilization will cease to be regarded as "universal" but different civilizations will learn to coexist and join to shape the future world.

Core state and fault line conflicts

In Huntington's view, intercivilizational conflict manifests itself in two forms: fault line conflicts and core state conflicts.Fault line conflicts are on a local level and occur between adjacent states belonging to different civilizations or within states that are home to populations from different civilizations.

Core state conflicts are on a global level between the major states of different civilizations. Core state conflicts can arise out of fault line conflicts when core states become involved.

These conflicts may result from a number of causes, such as: relative influence or power (military or economic), discrimination against people from a different civilization, intervention to protect kinsmen in a different civilization, or different values and culture, particularly when one civilization attempts to impose its values on people of a different civilization.

Modernization, Westernization, and "torn countries"

Critics of Huntington's ideas often extend their criticisms to traditional cultures and internal reformers who wish to modernize without adopting the values and attitudes of Western culture. These critics sometimes claim that to modernize it is necessary to become Westernized to a very large extent, so that sources of tension with the West will be reduced.Japan, China and the Four Asian Tigers have modernized in many respects while maintaining traditional or authoritarian societies which distinguish them from the West. Some of these countries have clashed with the West and some have not.

Perhaps the ultimate example of non-Western modernization is Russia, the core state of the Orthodox civilization. Huntington argues that Russia is primarily a non-Western state although he seems to agree that it shares a considerable amount of cultural ancestry with the modern West. According to Huntington, the West is distinguished from Orthodox Christian countries by its experience of the Renaissance, Reformation, the Enlightenment; by overseas colonialism rather than contiguous expansion and colonialism; and by the infusion of Classical culture through ancient Greece rather than through the continuous trajectory of the Byzantine Empire.

Huntington refers to countries that are seeking to affiliate with another civilization as "torn countries". Turkey, whose political leadership has systematically tried to Westernize the country since the 1920s, is his chief example. Turkey's history, culture, and traditions are derived from Islamic civilization, but Turkey's elite, beginning with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk who took power as first President in 1923, imposed Western institutions and dress, embraced the Latin alphabet, joined NATO, and has sought to join the European Union.

Mexico and Russia are also considered to be torn by Huntington. He also gives the example of Australia as a country torn between its Western civilizational heritage and its growing economic engagement with Asia.

According to Huntington, a torn country must meet three requirements to redefine its civilizational identity. Its political and economic elite must support the move. Second, the public must be willing to accept the redefinition. Third, the elites of the civilization that the torn country is trying to join must accept the country.

The book claims that to date no torn country has successfully redefined its civilizational identity, this mostly due to the elites of the 'host' civilization refusing to accept the torn country, though if Turkey gained membership in the European Union, it has been noted that many of its people would support Westernization, as in the following quote by EU Minister Egemen Bağış: "This is what Europe needs to do: they need to say that when Turkey fulfills all requirements, Turkey will become a member of the EU on date X. Then, we will regain the Turkish public opinion support in one day." If this were to happen, it would, according to Huntington, be the first to redefine its civilizational identity.

Criticism

Huntington has fallen under the stern critique of various left-leaning academic writers, who have either empirically, historically, logically, or ideologically challenged his claims (Fox, 2005; Mungiu Pippidi & Mindruta, 2002; Henderson & Tucker, 2001; Russett, Oneal, & Cox, 2000; Harvey, 2000).In an article explicitly referring to Huntington, scholar Amartya Sen (1999) argues:

diversity is a feature of most cultures in the world. Western civilization is no exception. The practice of democracy that has won out in the modern West is largely a result of a consensus that has emerged since the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, and particularly in the last century or so. To read in this a historical commitment of the West—over the millennia—to democracy, and then to contrast it with non-Western traditions (treating each as monolithic) would be a great mistake.In his 2003 book Terror and Liberalism, Paul Berman argues that distinct cultural boundaries do not exist in the present day. He argues there is no "Islamic civilization" nor a "Western civilization", and that the evidence for a civilization clash is not convincing, especially when considering relationships such as that between the United States and Saudi Arabia. In addition, he cites the fact that many Islamic extremists spent a significant amount of time living or studying in the Western world. According to Berman, conflict arises because of philosophical beliefs various groups share (or do not share), regardless of cultural or religious identity.

Timothy Garton Ash objects to the ‘extreme cultural determinism… crude to the point of parody’ of Huntington’s idea that Catholic and Protestant Europe is headed for democracy but that Orthodox Christian and Islamic Europe must accept dictatorship.

Edward Said issued a response to Huntington's thesis in his 2001 article, "The Clash of Ignorance". Said argues that Huntington's categorization of the world's fixed "civilizations" omits the dynamic interdependency and interaction of culture. A longtime critic of the Huntingtonian paradigm, and an outspoken proponent of Arab issues, Edward Said (2004) also argues that the clash of civilizations thesis is an example of "the purest invidious racism, a sort of parody of Hitlerian science directed today against Arabs and Muslims" (p. 293).

Noam Chomsky has criticized the concept of the clash of civilizations as just being a new justification for the United States "for any atrocities that they wanted to carry out", which was required after the Cold War as the Soviet Union was no longer a viable threat.

Intermediate Region

Huntington's geopolitical model, especially the structures for North Africa and Eurasia, is largely derived from the "Intermediate Region" geopolitical model first formulated by Dimitri Kitsikis and published in 1978. The Intermediate Region, which spans the Adriatic Sea and the Indus River, is neither Western nor Eastern (at least, with respect to the Far East) but is considered distinct.Concerning this region, Huntington departs from Kitsikis contending that a civilizational fault line exists between the two dominant yet differing religions (Eastern Orthodoxy and Sunni Islam), hence a dynamic of external conflict. However, Kitsikis establishes an integrated civilization comprising these two peoples along with those belonging to the less dominant religions of Shia Islam, Alevism, and Judaism. They have a set of mutual cultural, social, economic and political views and norms which radically differ from those in the West and the Far East.In the Intermediate Region, therefore, one cannot speak of a civilizational clash or external conflict, but rather an internal conflict, not for cultural domination, but for political succession. This has been successfully demonstrated by documenting the rise of Christianity from the Hellenized Roman Empire, the rise of the Islamic caliphates from the Christianized Roman Empire and the rise of Ottoman rule from the Islamic caliphates and the Christianized Roman Empire.

Mohammad Khatami, reformist president of Iran (in office 1997–2005), introduced the theory of Dialogue Among Civilizations as a response to Huntington's theory.

Opposing concepts

In recent years, the theory of Dialogue Among Civilizations, a response to Huntington's Clash of Civilizations, has become the center of some international attention. The concept was originally coined by Austrian philosopher Hans Köchler in an essay on cultural identity (1972). In a letter to UNESCO, Köchler had earlier proposed that the cultural organization of the United Nations should take up the issue of a "dialogue between different civilizations" (dialogue entre les différentes civilisations). In 2001, Iranian president Mohammad Khatami introduced the concept at the global level. At his initiative, the United Nations proclaimed the year 2001 as the "United Nations Year of Dialogue among Civilizations".The Alliance of Civilizations (AOC) initiative was proposed at the 59th General Assembly of the United Nations in 2005 by the Spanish Prime Minister, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero and co-sponsored by the Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The initiative is intended to galvanize collective action across diverse societies to combat extremism, to overcome cultural and social barriers between mainly the Western and predominantly Muslim worlds, and to reduce the tensions and polarization between societies which differ in religious and cultural values.

Geert Wilders, a Dutch politician best known for his intense criticism of Islam, has stated on several occasions that there is a clash between Western civilization and barbarism, referring to Islam.