From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Lysergic acid diethylamide (

LSD), also known as

acid, is a

hallucinogenic drug. Effects typically include altered thoughts, feelings, and awareness of one's surroundings. Many users

see or hear things that do not exist.

Dilated pupils, increased blood pressure, and increased body temperature are typical. Effects typically begin within half an hour and can last for up to 12 hours. It is used mainly as a

recreational drug and for

spiritual reasons.

While LSD does not appear to be

addictive,

tolerance with use of increasing doses may occur. Adverse psychiatric reactions such as

anxiety,

paranoia, and

delusions are possible. Long-term

flashbacks may occur despite no further use. Death as a result of LSD is very rare, though occasionally occurs via accidents. The effects of LSD are believed to occur as a result of alterations in the

serotonin system. As little as 20

micrograms can produce an effect. In pure form LSD is clear or white in color, has no smell, and is

crystalline. It breaks down with exposure to

ultraviolet light.

In the United States, as of 2017, about 10% of people have used

LSD at some point in their life, while 0.7% have used it in the last

year. It was most popular in the 1960s to 1980s. LSD is typically either swallowed or held under the tongue. It is most often sold on

blotter paper and less commonly as tablets or in

gelatin squares. There are no known treatments for addiction, if it occurs.

LSD was first

made by

Albert Hofmann in 1938 from

lysergic acid, a chemical from the fungus

ergot. Hofmann discovered its hallucinogenic properties in 1943. In the 1950s, the

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) believed the drug might be useful for

mind control so tested it on people, some without their knowledge, in a program called

MKUltra. LSD was sold as a medication for research purposes under the trade-name Delysid in the 1950s and 1960s. It was listed as a

schedule 1 controlled substance by the United Nations in 1971. It currently has no approved medical use. In Europe, as of 2011, the typical cost of a dose was between 4.50 and 25 Euro.

Uses

Recreational

Pink elephant blotters containing LSD

LSD is commonly used as a recreational drug.

Spiritual

LSD is considered an

entheogen

because it can catalyze intense spiritual experiences, during which

users may feel they have come into contact with a greater spiritual or

cosmic order. Users sometimes report

out of body experiences. In 1966,

Timothy Leary established the

League for Spiritual Discovery with LSD as its

sacrament.

Stanislav Grof has written that religious and mystical experiences observed during LSD sessions appear to be

phenomenologically indistinguishable from similar descriptions in the

sacred scriptures of the great religions of the world and the texts of ancient

civilizations.

Medical

LSD currently has no

approved uses in

medicine. A meta analysis concluded that a single dose was effective at reducing alcohol consumption in

alcoholism. LSD has also been studied in depression, anxiety, and drug dependence, with positive preliminary results.

Effects

Some symptoms reported for LSD.

Physical

LSD can cause

pupil dilation, reduced

appetite,

and wakefulness. Other physical reactions to LSD are highly variable

and nonspecific, some of which may be secondary to the psychological

effects of LSD. Among the reported symptoms are numbness, weakness,

nausea,

hypothermia or

hyperthermia, elevated

blood sugar,

goose bumps, heart rate increase, jaw clenching, perspiration,

saliva production,

mucus production,

hyperreflexia, and

tremors.

Psychological

The most common immediate psychological effects of LSD are

visual hallucinations and

illusions (colloquially known as "

trips"),

which can vary greatly depending on how much is used and how the brain

responds. Trips usually start within 20–30 minutes of taking LSD by

mouth (less if snorted or taken intravenously), peak three to four hours

after ingestion, and last up to 12 hours. Negative experiences,

referred to as "bad trips", produce intense negative emotions, such as

irrational fears and anxiety, panic attacks, paranoia, rapid mood

swings,

intrusive thoughts of hopelessness, wanting to harm others, and

suicidal ideation. It is impossible to predict when a bad trip will occur.

Good trips are stimulating and pleasurable, and typically involve

feeling as if one is floating, disconnected from reality, feelings of

joy or euphoria (sometimes called a "rush"), decreased inhibitions, and

the belief that one has extreme mental clarity or superpowers.

Sensory

Some sensory effects may include an experience of radiant colors,

objects and surfaces appearing to ripple or "breathe", colored patterns

behind the closed eyelids (

eidetic imagery),

an altered sense of time (time seems to be stretching, repeating

itself, changing speed or stopping), crawling geometric patterns

overlaying walls and other objects, and morphing objects. Some users, including Albert Hofmann, report a strong metallic taste for the duration of the effects.

LSD causes an

animated sensory experience of

senses,

emotions,

memories, time, and

awareness

for 6 to 14 hours, depending on dosage and tolerance. Generally

beginning within 30 to 90 minutes after ingestion, the user may

experience anything from subtle changes in perception to overwhelming

cognitive shifts. Changes in auditory and visual perception are typical. Visual effects include the illusion of

movement of static surfaces ("walls breathing"),

after image-like

trails of moving objects ("tracers"), the appearance of moving colored

geometric patterns (especially with closed eyes), an intensification of

colors and brightness ("sparkling"), new textures on objects, blurred

vision, and shape suggestibility. Some users report that the inanimate

world appears to animate in an inexplicable way; for instance, objects

that are static in three dimensions can seem to be moving relative to

one or more additional spatial dimensions. Many of the basic visual effects resemble the

phosphenes seen after applying pressure to the eye and have also been studied under the name "

form constants". The auditory effects of LSD may include

echo-like

distortions of sounds, changes in ability to discern concurrent

auditory stimuli, and a general intensification of the experience of

music. Higher doses often cause intense and fundamental distortions of

sensory perception such as

synaesthesia, the experience of additional spatial or temporal dimensions, and temporary

dissociation.

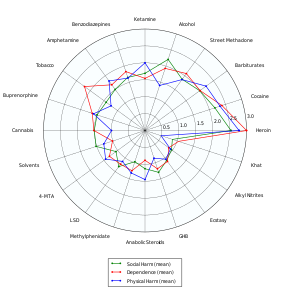

Adverse effects

Addiction

experts in psychiatry, chemistry, pharmacology, forensic science,

epidemiology, and the police and legal services engaged in

delphic analysis regarding 20 popular recreational drugs. LSD was ranked 14th in dependence, 15th in physical harm, and 13th in social harm.

Of the 20 drugs ranked according to individual and societal harm by

David Nutt,

LSD was third to last, approximately 1/10th as harmful as alcohol. The

most significant adverse effect was impairment of mental functioning

while intoxicated.

Mental disorders

LSD may trigger

panic attacks

or feelings of extreme anxiety, known familiarly as a "bad trip." Review studies suggest that LSD likely plays a role in precipitating the

onset of acute psychosis in previously healthy individuals with an

increased likelihood in individuals who have a family history of

schizophrenia. There is evidence that people with severe mental illnesses like

schizophrenia have a higher likelihood of experiencing adverse effects from taking LSD.

Suggestibility

While publicly available documents indicate that the

CIA and

Department of Defense have discontinued research into the use of LSD as a means of

mind control, research from the 1960s suggests that both mentally ill and healthy people are more

suggestible while under its influence.

Flashbacks

Some individuals may experience "

flashbacks" and a syndrome of long-term and occasionally distressing perceptual changes.

"Flashbacks" are a reported psychological phenomenon in which an

individual experiences an episode of some of LSD's subjective effects

after the drug has worn off, "persisting for months or years after

hallucinogen use".

Several studies have tried to determine the likelihood that a user of

LSD, not suffering from known psychiatric conditions, will experience

flashbacks. The larger studies include Blumenfeld's in 1971and Naditch and Fenwick's in 1977, which arrived at figures of 20% and 28%, respectively.

Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder

(HPPD) describes a post-LSD exposure syndrome in which LSD-like visual

changes are not temporary and brief, as they are in flashbacks, but

instead are persistent, and cause clinically significant impairment or

distress. The syndrome is a

DSM-IV diagnosis. Several scientific journal articles have described the disorder.

HPPD differs from flashbacks in that it is persistent and apparently

entirely visual (although mood and anxiety disorders are sometimes

diagnosed in the same individuals). A recent review suggests that

HPPD (as defined in the DSM-IV) is uncommon and affects a distinctly vulnerable subpopulation of users.

Cancer and pregnancy

The

mutagenic potential of LSD is unclear. Overall, the evidence seems to point to limited or no effect at commonly used doses. Empirical studies showed no evidence of

teratogenic or mutagenic effects from use of LSD in man.

Tolerance

Tolerance to LSD builds up over consistent use and

cross-tolerance has been demonstrated between LSD,

mescaline

and

psilocybin.

This tolerance is probably caused by

downregulation of

5-HT2A receptors in the brain and diminishes a few days after cessation of use.

LSD is not addictive. Experimental evidence has demonstrated that LSD use does not yield

positive reinforcement in either human or animal subjects.

Overdose

As of 2008 there were no documented fatalities attributed directly to an LSD overdose. Despite this several behavioral fatalities and suicides have occurred due to LSD.

Eight individuals who accidentally consumed very high amounts by

mistaking LSD for cocaine developed comatose states, hyperthermia,

vomiting, gastric bleeding, and respiratory problems–however, all

survived with supportive care.

Reassurance in a calm, safe environment is beneficial. Agitation can be safely addressed with

benzodiazepines such as

lorazepam or

diazepam.

Neuroleptics such as

haloperidol

are recommended against because they may have adverse effects. LSD is

rapidly absorbed, so activated charcoal and emptying of the stomach will

be of little benefit, unless done within 30–60 minutes of ingesting an

overdose of LSD. Sedation or physical restraint is rarely required, and

excessive restraint may cause complications such as

hyperthermia (over-heating) or

rhabdomyolysis.

Research suggests that massive doses are not lethal, but do typically require supportive care, which may include

endotracheal intubation or respiratory support. It is recommended that high blood pressure,

tachycardia

(rapid heart-beat), and hyperthermia, if present, are treated

symptomatically, and that low blood pressure is treated initially with

fluids and then with

pressors if necessary. Intravenous administration of

anticoagulants,

vasodilators, and

sympatholytics may be useful with massive doses.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Binding affinities of LSD for various receptors. The lower the

dissociation constant (K

i),

the more strongly LSD binds to that receptor (i.e. with higher

affinity). The horizontal line represents an approximate value for human

plasma concentrations of LSD, and hence, receptor affinities that are

above the line are unlikely to be involved in LSD's effect. Data

averaged from data from the

Ki Database

Most

serotonergic psychedelics are not significantly

dopaminergic, and LSD is therefore atypical in this regard. The agonism of the

D2 receptor by LSD may contribute to its psychoactive effects in humans.

LSD binds to most serotonin receptor subtypes except for the

5-HT3 and

5-HT4 receptors.

However, most of these receptors are affected at too low affinity to be

sufficiently activated by the brain concentration of approximately

10–20

nM. In humans, recreational doses of LSD can affect

5-HT1A (K

i=1.1nM),

5-HT2A (K

i=2.9nM),

5-HT2B (K

i=4.9nM),

5-HT2C (K

i=23nM),

5-HT5A (K

i=9nM [in cloned rat tissues]), and

5-HT6 receptors (K

i=2.3nM).

5-HT5B receptors, which are not present in humans, also have a high affinity for LSD. The psychedelic effects of LSD are attributed to

cross-activation of 5-HT

2A receptor heteromers. Many but not all 5-HT

2A agonists are psychedelics and 5-HT

2A antagonists block the psychedelic activity of LSD. LSD exhibits

functional selectivity at the 5-HT

2A and 5HT

2C receptors in that it activates the

signal transduction enzyme

phospholipase A2 instead of activating the enzyme

phospholipase C as the endogenous ligand serotonin does. Exactly how LSD produces its effects is unknown, but it is thought that it works by increasing

glutamate release in the

cerebral cortex and therefore

excitation in this area, specifically in layers IV and V. LSD, like many other drugs of recreational use, has been shown to activate

DARPP-32-related pathways. The drug enhances dopamine D

2 receptor

protomer recognition and

signaling of D

2–5-HT

2A receptor complexes, which may contribute to its psychotic effects.

The

crystal structure of LSD bound in its active state to a

serotonin receptor, specifically the 5-HT

2B receptor, has recently (2017) been elucidated for the first time. The LSD-bound 5-HT

2B receptor is regarded as an excellent model system for the 5-HT

2A receptor and the structure of the LSD-bound 5-HT

2B receptor was used in the study as a template to determine the structural features necessary for the activity of LSD at the 5-HT

2A receptor.

The diethylamide moiety of LSD was found to be a key component for its

activity, which is in accordance with the fact that the related

lysergamide lysergic acid amide (LSA) is far less hallucinogenic in comparison. LSD was found to stay bound to both the 5-HT

2A and 5-HT

2B receptors for an exceptionally long amount of time, which may be responsible for its long

duration of action in spite of its relatively short terminal half-life.

The extracellular loop 2 leucine 209 residue of the 5-HT2B receptor

forms a 'lid' over LSD that appears to trap it in the receptor, and this

was implicated in the

potency and

functional selectivity of LSD and its very slow

dissociation rate from the 5-HT

2 receptors.

Pharmacokinetics

The effects of LSD normally last between 6 and 12 hours depending on dosage, tolerance, body weight, and age. The Sandoz prospectus for "Delysid" warned: "intermittent disturbances of affect may occasionally persist for several days."

Contrary to early reports and common belief, LSD effects do not last

longer than the amount of time significant levels of the drug are

present in the blood. Aghajanian and Bing (1964) found LSD had an elimination half-life of only 175 minutes (about 3 hours).

However, using more accurate techniques, Papac and Foltz (1990)

reported that 1 µg/kg oral LSD given to a single male volunteer had an

apparent plasma half-life of 5.1 hours, with a peak plasma concentration

of 5 ng/mL at 3 hours post-dose.

The

pharmacokinetics

of LSD were not properly determined until 2015, which is not surprising

for a drug with the kind of low-μg potency that LSD possesses. In a sample of 16 healthy subjects, a single mid-range 200 μg oral dose of LSD was found to produce mean

maximal concentrations of 4.5 ng/mL at a median of 1.5 hours (range 0.5–4 hours) post-administration. After attainment of peak levels, concentrations of LSD decreased following

first-order kinetics with a

terminal half-life of 3.6 hours for up to 12 hours and then with slower

elimination with a terminal half-life of 8.9 hours thereafter.

The effects of the dose of LSD given lasted for up to 12 hours and were

closely correlated with the concentrations of LSD present in

circulation over time, with no acute

tolerance observed. Only 1% of the drug was eliminated in

urine unchanged whereas 13% was eliminated as the major

metabolite 2-oxo-3-hydroxy-LSD (O-H-LSD) within 24 hours. O-H-LSD is formed by

cytochrome P450 enzymes,

although the specific enzymes involved are unknown, and it does not

appear to be known whether O-H-LSD is pharmacologically active or not. The oral

bioavailability of LSD was crudely estimated as approximately 71% using previous data on

intravenous administration of LSD. The sample was equally divided between male and female subjects and

there were no significant sex differences observed in the

pharmacokinetics of LSD.

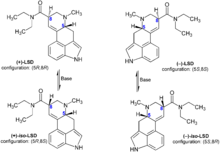

Chemistry

The four possible stereoisomers of LSD. Only (+)-LSD is psychoactive.

LSD is a

chiral compound with two

stereocenters at the

carbon atoms C-5 and C-8, so that theoretically four different

optical isomers of LSD could exist. LSD, also called (+)-

D-LSD, has the

absolute configuration (5

R,8

R). The C-5

isomers of lysergamides do not exist in nature and are not formed during the synthesis from

d-lysergic acid.

Retrosynthetically,

the C-5 stereocenter could be analysed as having the same configuration

of the alpha carbon of the naturally occurring amino acid L-

tryptophan, the precursor to all biosynthetic ergoline compounds.

However, LSD and iso-LSD, the two C-8 isomers, rapidly interconvert in the presence of

bases, as the alpha proton is acidic and can be

deprotonated and reprotonated. Non-psychoactive iso-LSD which has formed during the synthesis can be separated by

chromatography and can be isomerized to LSD.

Pure salts of LSD are

triboluminescent, emitting small flashes of white light when shaken in the dark. LSD is strongly

fluorescent and will glow bluish-white under

UV light.

Synthesis

LSD is an

ergoline derivative. It is commonly synthesized by reacting

diethylamine with an activated form of

lysergic acid. Activating reagents include

phosphoryl chloride and

peptide coupling reagents. Lysergic acid is made by alkaline

hydrolysis of lysergamides like

ergotamine, a substance usually derived from the

ergot fungus on

agar plate; or, theoretically possible, but impractical and uncommon, from

ergine (lysergic acid amide, LSA) extracted from

morning glory seeds. Lysergic acid can also be produced synthetically, eliminating the need for ergotamines.

Dosage

White on White blotters (WoW) for sublingual administration

A single dose of LSD may be between 40 and 500 micrograms—an amount

roughly equal to one-tenth the mass of a grain of sand. Threshold

effects can be felt with as little as 25 micrograms of LSD. Dosages of LSD are measured in

micrograms (µg), or millionths of a gram. By comparison, dosages of most drugs, both recreational and medicinal, are measured in

milligrams (mg), or thousandths of a gram. For example, an active dose of

mescaline, roughly

0.2 to 0.5 g, has effects comparable to 100 µg or less of LSD.

In the mid-1960s, the most important

black market LSD manufacturer (

Owsley Stanley) distributed acid at a standard concentration of 270 µg,

while street samples of the 1970s contained 30 to 300 µg. By the 1980s,

the amount had reduced to between 100 and 125 µg, dropping more in the

1990s to the 20–80 µg range, and even more in the 2000s (decade).

Reactivity and degradation

"LSD," writes the chemist

Alexander Shulgin,

"is an unusually fragile molecule… As a salt, in water, cold, and free

from air and light exposure, it is stable indefinitely."

LSD has two

labile protons at the tertiary stereogenic C5 and C8 positions, rendering these centres prone to

epimerisation. The C8 proton is more labile due to the electron-withdrawing

carboxamide attachment, but removal of the

chiral proton at the C5 position (which was once also an alpha proton of the parent molecule

tryptophan) is assisted by the inductively withdrawing nitrogen and pi electron delocalisation with the

indole ring.

LSD also has

enamine-type reactivity because of the electron-donating effects of the indole ring. Because of this,

chlorine

destroys LSD molecules on contact; even though chlorinated tap water

contains only a slight amount of chlorine, the small quantity of

compound typical to an LSD solution will likely be eliminated when

dissolved in tap water. The

double bond between the 8-position and the

aromatic ring, being conjugated with the indole ring, is susceptible to

nucleophilic attacks by water or

alcohol, especially in the presence of light. LSD often converts to "lumi-LSD", which is inactive in human beings.

A controlled study was undertaken to determine the stability of LSD in pooled urine samples.

The concentrations of LSD in urine samples were followed over time at

various temperatures, in different types of storage containers, at

various exposures to different wavelengths of light, and at varying pH

values. These studies demonstrated no significant loss in LSD

concentration at 25 °C for up to four weeks. After four weeks of

incubation, a 30% loss in LSD concentration at 37 °C and up to a 40% at

45 °C were observed. Urine fortified with LSD and stored in amber glass

or nontransparent polyethylene containers showed no change in

concentration under any light conditions. Stability of LSD in

transparent containers under light was dependent on the distance between

the light source and the samples, the wavelength of light, exposure

time, and the intensity of light. After prolonged exposure to heat in

alkaline pH conditions, 10 to 15% of the parent LSD epimerized to

iso-LSD. Under acidic conditions, less than 5% of the LSD was converted

to iso-LSD. It was also demonstrated that trace amounts of metal ions in

buffer or urine could catalyze the decomposition of LSD and that this

process can be avoided by the addition of

EDTA.

Detection in body fluids

LSD may be quantified in urine as part of a

drug abuse testing program,

in plasma or serum to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized

victims or in whole blood to assist in a forensic investigation of a

traffic or other criminal violation or a case of sudden death. Both the

parent drug and its major metabolite are unstable in biofluids when

exposed to light, heat or alkaline conditions and therefore specimens

are protected from light, stored at the lowest possible temperature and

analyzed quickly to minimize losses.

The apparent plasma half life of LSD is considered to be around

5.1 hours with peak plasma concentrations occurring 3 hours after

administration.

History

... affected by a

remarkable restlessness, combined with a slight dizziness. At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures,

extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors. After some two hours this condition faded away. — Albert Hofmann, on his first experience with LSD

LSD was first synthesized on November 16, 1938 by Swiss chemist

Albert Hofmann at the Sandoz Laboratories in

Basel,

Switzerland as part of a large research program searching for medically useful

ergot alkaloid derivatives. LSD's

psychedelic properties were discovered 5 years later when Hofmann himself accidentally ingested an unknown quantity of the chemical. The first intentional ingestion of LSD occurred on April 19, 1943, when Hofmann ingested 250

µg

of LSD. He said this would be a threshold dose based on the dosages of

other ergot alkaloids. Hofmann found the effects to be much stronger

than he anticipated.

Sandoz Laboratories introduced LSD as a psychiatric drug in 1947 and

marketed LSD as a psychiatric panacea, hailing it "as a cure for

everything from schizophrenia to criminal behavior, ‘sexual

perversions,’ and alcoholism.”

Beginning in the 1950s, the US

Central Intelligence Agency began a research program code named

Project MKULTRA.

Experiments included administering LSD to CIA employees, military

personnel, doctors, other government agents, prostitutes, mentally ill

patients, and members of the general public in order to study their

reactions, usually without the subjects' knowledge. The project was

revealed in the US congressional

Rockefeller Commission report in 1975.

In 1963, the Sandoz patents expired on LSD. Several figures, including

Aldous Huxley,

Timothy Leary, and

Al Hubbard, began to advocate the consumption of LSD. LSD became central to the counterculture of the 1960s.

In the early 1960s the use of LSD and other hallucinogens was advocated

by new proponents of consciousness expansion such as Leary, Huxley,

Alan Watts and

Arthur Koestler, and according to L. R. Veysey they profoundly influenced the thinking of the new generation of youth.

On October 24, 1968, possession of LSD was made illegal in the United States. The last

FDA

approved study of LSD in patients ended in 1980, while a study in

healthy volunteers was made in the late 1980s. Legally approved and

regulated psychiatric use of LSD continued in Switzerland until 1993.

Society and culture

Counterculture, music and art

Psychedelic art attempts to capture the visions experienced on a psychedelic trip

By the mid-1960s, the youth

countercultures in

California, particularly in

San Francisco, had adopted the use of hallucinogenic drugs, with the first major underground LSD factory established by

Owsley Stanley. From 1964,

the Merry Pranksters, a loose group that developed around novelist

Ken Kesey, sponsored the

Acid Tests, a series of events primarily staged in or near

San Francisco,

involving the taking of LSD (supplied by Stanley), accompanied by light

shows, film projection and discordant, improvised music known as the

psychedelic symphony.

The Pranksters helped popularize LSD use, through their road trips

across America in a psychedelically-decorated converted school bus,

which involved distributing the drug and meeting with major figures of

the beat movement, and through publications about their activities such

as

Tom Wolfe's

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968).

In both music and art, the influence of LSD was soon being more widely

seen and heard thanks to the bands that participated in the Acid Tests

and related events, including

the Grateful Dead,

Jefferson Airplane and

Big Brother and the Holding Company, and through the inventive poster and album art of San Francisco-based artists like

Rick Griffin,

Victor Moscoso,

Bonnie MacLean,

Stanley Mouse and

Alton Kelley, and

Wes Wilson, meant to evoke the visual experience of an LSD trip.

In San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, brothers Ron and

Jay Thelin opened the Psychedelic Shop in January 1966. The Thelins'

store is regarded as the first ever

head shop.

The Thelins opened the store to promote safe use of LSD, which was then

still legal in California. The Psychedelic Shop helped to further

popularize LSD in the Haight and to make the neighborhood the unofficial

capital of the hippie counterculture in the United States. Ron Thelin

was also involved in organizing the Love Pageant rally, a protest held

in Golden Gate park to protest California's newly adopted ban on LSD in

October 1966. At the rally, hundreds of attendees took acid in unison. Although the Psychedelic Shop closed after barely a year-and-a-half in

business, its role in popularizing LSD was considerable.

A similar and connected nexus of LSD use in the creative arts developed around the same time in

London. A key figure in this phenomenon in the UK was British academic

Michael Hollingshead,

who first tried LSD in America in 1961 while he was the Executive

Secretary for the Institute of British-American Cultural Exchange. After

being given a large quantity of pure Sandoz LSD (which was still legal

at the time) and experiencing his first "trip", Hollingshead contacted

Aldous Huxley, who suggested that he get in touch with Harvard academic

Timothy Leary, and over the next few years, in concert with Leary and

Richard Alpert, Hollingshead played a major role in their famous LSD research at

Millbrook

before moving to New York City, where he conducted his own LSD

experiments. In 1965 Hollingshead returned to the UK and founded the

World Psychedelic Center in

Chelsea, London. Among the many famous people in the UK that Hollingshead is reputed to have introduced to LSD are artist and

Hipgnosis founder

Storm Thorgerson, and musicians

Donovan,

Keith Richards,

Paul McCartney,

John Lennon, and

George Harrison.

Although establishment concern about the new drug led to it being

declared an illegal drug by the Home Secretary in 1966, LSD was soon

being used widely in the upper echelons of the British art and music

scene, including members of

the Beatles,

the Rolling Stones,

the Moody Blues,

the Small Faces,

Pink Floyd,

Jimi Hendrix

and others, and the products of these experiences were soon being both

heard and seen by the public with singles like The Small Faces' "

Itchycoo Park" and LPs like the Beatles'

Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band and Cream's

Disraeli Gears,

which featured music that showed the obvious influence of the

musicians' recent psychedelic excursions, and which were packaged in

elaborately-designed album covers that featured vividly-coloured

psychedelic artwork by artists like

Peter Blake,

Martin Sharp,

Hapshash and the Coloured Coat (

Nigel Waymouth and

Michael English) and art/music collective "

The Fool".

In the 1960s, musicians from

psychedelic music and

psychedelic rock

bands began to refer (at first indirectly, and later explicitly) to the

drug and attempted to recreate or reflect the experience of taking LSD

in their music. A number of features are often included in psychedelic

music. Exotic instrumentation, with a particular fondness for the

sitar and

tabla are common. Electric guitars are used to create

feedback, and are played through

wah wah and

fuzzbox effect pedals. Elaborate studio effects are often used, such as

backwards tapes,

panning,

phasing, long

delay loops, and extreme

reverb. In the 1960s there was a use of primitive electronic instruments such as early synthesizers and the

theremin. Later forms of electronic psychedelia also employed repetitive computer-generated beats. Songs allegedly referring to LSD include

John Prine's "Illegal Smile" and

The Beatles' song

Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, although the authors of the latter song repeatedly denied this claim. Psychedelic experiences were also reflected in

psychedelic art,

literature and

film.

LSD had a strong influence on the

Grateful Dead and the culture of

Deadheads, as well as the impact for artist

Keith Haring, early

techno music, and the

jam band Phish.

Legal status

The

United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances

(adopted in 1971) requires the signing parties to prohibit LSD. Hence,

it is illegal in all countries that were parties to the convention,

including the

United States,

Australia,

New Zealand, and most of

Europe.

However, enforcement of those laws varies from country to country.

Medical and scientific research with LSD in humans is permitted under

the 1971 UN Convention.

Australia

LSD is a

Schedule 9 prohibited substance in Australia under the

Poisons Standard (February 2017).

A Schedule 9 substance is defined as a substance which may be abused or

misused, the manufacture, possession, sale or use of which should be

prohibited by law except when required for medical or scientific

research, or for analytical, teaching or training purposes with approval

of Commonwealth and/or State or Territory Health Authorities.

In

Western Australia section 9 of the

Misuse of Drugs Act 1981

provides for summary trial before a magistrate for possession of less

than 0.004g; section 11 provides rebuttable presumptions of intent to

sell or supply if the quantity is 0.002g or more, or of possession for

the purpose of trafficking if 0.01g.

Canada

In

Canada, LSD is a controlled substance under Schedule III of the

Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

Every person who seeks to obtain the substance, without disclosing

authorization to obtain such substances 30 days before obtaining another

prescription from a practitioner, is guilty of an indictable offense

and liable to

imprisonment

for a term not exceeding 3 years. Possession for purpose of trafficking

is an indictable offense punishable by imprisonment for 10 years.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, LSD is a Schedule 1 Class 'A' drug. This means

it has no recognized legitimate uses and possession of the drug without

a license is punishable with 7 years' imprisonment and/or an unlimited

fine, and trafficking is punishable with life imprisonment and an

unlimited fine (

see main article on drug punishments Misuse of Drugs Act 1971).

In 2000, after consultation with members of the

Royal College of Psychiatrists' Faculty of Substance Misuse, the UK Police Foundation issued the

Runciman Report which recommended

"the transfer of LSD from Class A to Class B".

In November 2009, the UK

Transform Drug Policy Foundation released in the House of Commons a guidebook to the legal regulation of drugs,

After the War on Drugs: Blueprint for Regulation, which details options for regulated distribution and sale of LSD and other psychedelics.

United States

LSD is Schedule I in the United States, according to the

Controlled Substances Act of 1970. This means LSD is illegal to manufacture, buy, possess, process, or distribute without a license from the

Drug Enforcement Administration

(DEA). By classifying LSD as a Schedule I substance, the DEA holds that

LSD meets the following three criteria: it is deemed to have a high

potential for abuse; it has no legitimate medical use in treatment; and

there is a lack of accepted safety for its use under medical

supervision. There are no documented deaths from chemical

toxicity; most LSD deaths are a result of behavioral toxicity.

There can also be substantial discrepancies between the amount of

chemical LSD that one possesses and the amount of possession with which

one can be charged in the US. This is because LSD is almost always

present in a medium (e.g. blotter or neutral liquid), and the amount

that can be considered with respect to sentencing is the total mass of

the drug and its medium. This discrepancy was the subject of 1995

United States Supreme Court case,

Neal v. United States.

Lysergic acid and

lysergic acid amide, LSD precursors, are both classified in

Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act.

Ergotamine tartrate, a precursor to lysergic acid, is regulated under the

Chemical Diversion and Trafficking Act.

Mexico

In April 2009, the Mexican Congress approved changes in the General

Health Law that decriminalized the possession of illegal drugs for

immediate consumption and personal use, allowing a person to possess a

moderate amount of LSD. The only restriction is that people in

possession of drugs should not be within a 300-meter radius of schools,

police departments, or correctional facilities. Marijuana, along with

cocaine, opium, heroin, and other drugs were also decriminalized; their

possession is not considered a crime as long as the dose does not exceed

the limit established in the General Health Law. Many

question this, as cocaine is as synthesised as heroin, and both are

produced as extracts from plants. The law establishes very low amount

thresholds and strictly defines personal dosage. For those arrested with

more than the threshold allowed by the law this can result in heavy

prison sentences, as they will be assumed to be small traffickers even

if there are no other indications that the amount was meant for selling.

Czech Republic

In the

Czech Republic, until 31 December 1998 only drug possession "

for other person"

(i.e. intent to sell) was criminal (apart from production, importation,

exportation, offering or mediation, which was and remains criminal)

while possession for personal use remained legal.

On 1 January 1999, an amendment of the Criminal Code, which was necessitated in order to align the Czech drug rules with the

Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, became effective, criminalizing possession of "

amount larger than small"

also for personal use (Art. 187a of the Criminal Code) while possession

of small amounts for personal use became a misdemeanor.

The judicial practice came to the conclusion that the "

amount larger than small" must be five to ten times larger (depending on drug) than a usual single dose of an average consumer.

Under the Regulation No. 467/2009 Coll, possession of less than 5

doses of LSD was to be considered smaller than large for the purposes

of the Criminal Code and was to be treated as a misdemeanor subject to a

fine equal to a parking ticket.

Ecuador

According to the

2008 Constitution of Ecuador, in its Article 364, the Ecuadorian state does not see drug consumption as a crime but only as a health concern.

Since June 2013 the State drugs regulatory office CONSEP has published a

table which establishes maximum quantities carried by persons so as to

be considered in legal possession and that person as not a seller of

drugs.

The "CONSEP established, at their latest general meeting, that the

0.020 milligrams of LSD shall be considered the maximum consumer amount.

Economics

Production

Glassware seized by the DEA

An active dose of LSD is very minute, allowing a large number of

doses to be synthesized from a comparatively small amount of raw

material. Twenty five kilograms of precursor

ergotamine tartrate

can produce 5–6 kg of pure crystalline LSD; this corresponds to

100 million doses. Because the masses involved are so small, concealing

and transporting illicit LSD is much easier than smuggling

cocaine,

cannabis, or other illegal drugs.

Manufacturing LSD requires laboratory equipment and experience in the field of

organic chemistry.

It takes two to three days to produce 30 to 100 grams of pure compound.

It is believed that LSD is not usually produced in large quantities,

but rather in a series of small batches. This technique minimizes the

loss of precursor chemicals in case a step does not work as expected.

Forms

Five doses of LSD, often called a "five strip"

LSD is produced in crystalline form and then mixed with

excipients

or redissolved for production in ingestible forms. Liquid solution is

either distributed in small vials or, more commonly, sprayed onto or

soaked into a distribution medium. Historically, LSD solutions were

first sold on sugar cubes, but practical considerations forced a change

to

tablet

form. Appearing in 1968 as an orange tablet measuring about 6 mm

across, "Orange Sunshine" acid was the first largely available form of

LSD after its possession was made illegal.

Tim Scully, a prominent chemist, made some of these tablets, but said that most "Sunshine" in the USA came by way of

Ronald Stark, who imported approximately thirty-five million doses from Europe.

Over a period of time, tablet dimensions, weight, shape and

concentration of LSD evolved from large (4.5–8.1 mm diameter),

heavyweight (≥150 mg), round, high concentration (90–350 µg/tab) dosage

units to small (2.0–3.5 mm diameter) lightweight (as low as 4.7 mg/tab),

variously shaped, lower concentration (12–85 µg/tab, average range

30–40 µg/tab) dosage units. LSD tablet shapes have included cylinders,

cones, stars, spacecraft, and heart shapes. The smallest tablets became

known as "Microdots".

After tablets came "computer acid" or "blotter paper LSD", typically made by dipping a preprinted sheet of

blotting paper into an LSD/water/alcohol solution.

More than 200 types of LSD tablets have been encountered since 1969 and

more than 350 blotter paper designs have been observed since 1975. About the same time as blotter paper LSD came "Windowpane" (AKA "Clearlight"), which contained LSD inside a thin

gelatin square a quarter of an inch (6 mm) across.

LSD has been sold under a wide variety of often short-lived and

regionally restricted street names including Acid, Trips, Uncle Sid,

Blotter,

Lucy, Alice and doses, as well as names that reflect the designs on the sheets of blotter paper. Authorities have encountered the drug in other forms—including powder or crystal, and capsule.

Modern distribution

LSD manufacturers and traffickers in the

United States

can be categorized into two groups: A few large-scale producers, and an

equally limited number of small, clandestine chemists, consisting of

independent producers who, operating on a comparatively limited scale,

can be found throughout the country. As a group, independent producers are of less concern to the

Drug Enforcement Administration than the larger groups because their product reaches only local markets.

Many LSD dealers and chemists describe a religious or

humanitarian purpose that motivates their illicit activity. Nicholas

Schou's book

Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love, and Acid to the World describes one such group,

the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. The group was a major American LSD trafficking group in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

In the second half of the 20th century, dealers and chemists loosely associated with the

Grateful Dead like

Owsley Stanley,

Nicholas Sand, Karen Horning, Sarah Maltzer, "Dealer McDope," and

Leonard Pickard played an essential role in distributing LSD.

Mimics

LSD blotter acid mimic actually containing DOC

Different blotters which could possibly be mimics

Since 2005, law enforcement in the United States and elsewhere has

seized several chemicals and combinations of chemicals in blotter paper

which were sold as LSD mimics, including

DOB, a mixture of

DOC and

DOI,

25I-NBOMe, and a mixture of

DOC and

DOB.

Street users of LSD are often under the impression that blotter paper

which is actively hallucinogenic can only be LSD because that is the

only chemical with low enough doses to fit on a small square of blotter

paper. While it is true that LSD requires lower doses than most other

hallucinogens, blotter paper is capable of absorbing a much larger

amount of material. The DEA performed a

chromatographic analysis of blotter paper containing

2C-C

which showed that the paper contained a much greater concentration of

the active chemical than typical LSD doses, although the exact quantity

was not determined. Blotter LSD mimics can have relatively small dose squares; a sample of blotter paper containing

DOC seized by

Concord, California police had dose markings approximately 6 mm apart. Several deaths have been attributed to 25I-NBOMe.

Research

A number of organizations—including

the Beckley Foundation,

MAPS,

Heffter Research Institute and the

Albert Hofmann

Foundation—exist to fund, encourage and coordinate research into the

medicinal and spiritual uses of LSD and related psychedelics. New clinical LSD experiments in humans started in 2009 for the first time in 35 years. As it is illegal in many areas of the world, potential medical uses are difficult to study.

In 2001 the

United States Drug Enforcement Administration stated that LSD "produces no aphrodisiac effects, does not increase creativity, has no lasting positive effect in treating

alcoholics or

criminals, does not produce a '

model psychosis', and does not generate immediate personality change." More recently, experimental uses of LSD have included the treatment of alcoholism and pain and cluster headache relief.

Psychedelic therapy

In the 1950s and 1960s LSD was used in psychiatry to enhance psychotherapy known as

psychedelic therapy. Some psychiatrists believed LSD was especially useful at helping patients to "unblock" repressed subconscious material through other

psychotherapeutic methods, and also for treating alcoholism. One study concluded, "The root of the therapeutic value of the LSD experience is its potential for producing

self-acceptance and self-surrender," presumably by forcing the user to face issues and problems in that individual's psyche.

Two recent reviews concluded that conclusions drawn from most of these early trials are unreliable due to serious

methodological flaws. These include the absence of adequate

control groups, lack of followup, and vague criteria for

therapeutic

outcome. In many cases studies failed to convincingly demonstrate

whether the drug or the therapeutic interaction was responsible for any

beneficial effects.

In recent years organizations like the

Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies have renewed clinical research of LSD.

Other uses

In the 1950s and 1960s, some psychiatrists (e.g.

Oscar Janiger)

explored the potential effect of LSD on creativity. Experimental

studies attempted to measure the effect of LSD on creative activity and

aesthetic appreciation.

Since 2008 there has been ongoing research into using LSD to alleviate anxiety for

terminally ill cancer patients coping with their impending deaths.

A 2012 meta-analysis found evidence that a single dose of LSD in

conjunction with various alcoholism treatment programs was associated

with a decrease in alcohol abuse, lasting for several months, but no

effect was seen at one year. Adverse events included seizure, moderate

confusion and agitation, nausea,

vomiting, and acting in a bizarre fashion.

LSD has been used as a treatment for

cluster headaches with positive results in some small studies.

Notable individuals

Some notable individuals have commented publicly on their experiences with LSD.

Some of these comments date from the era when it was legally available

in the US and Europe for non-medical uses, and others pertain to

psychiatric

treatment in the 1950s and 1960s. Still others describe experiences

with illegal LSD, obtained for philosophic, artistic, therapeutic,

spiritual, or recreational purposes.

- Richard Feynman, a notable physicist at California Institute of Technology,

tried LSD during his professorship at Caltech. Feynman largely

sidestepped the issue when dictating his anecdotes; he mentions it in

passing in the "O Americano, Outra Vez" section.

- Jerry Garcia stated in a July 3, 1989 interview for Relix Magazine,

in response to the question "Have your feelings about LSD changed over

the years?," "They haven't changed much. My feelings about LSD are

mixed. It's something that I both fear and that I love at the same time.

I never take any psychedelic, have a psychedelic experience, without

having that feeling of, "I don't know what's going to happen." In that

sense, it's still fundamentally an enigma and a mystery."

- Bill Gates implied in an interview with Playboy that he tried LSD during his youth.

- Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World, became a user of psychedelics after moving to Hollywood. He was at the forefront of the counterculture's experimentation with psychedelic drugs, which led to his 1954 work The Doors of Perception. Dying from cancer, he asked his wife on 22 November 1963 to inject him with 100 µg of LSD. He died later that day.

- Steve Jobs, co-founder and former CEO of Apple Inc., said, "Taking LSD was a profound experience, one of the most important things in my life."

- In a 2004 interview, Paul McCartney said that The Beatles' songs "Day Tripper" and "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" were inspired by LSD trips. Nonetheless, John Lennon

consistently stated over the course of many years that the fact that

the initials of "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" spelled out L-S-D was a

coincidence (the title came from a picture drawn by his son Julian) and that the band members did not notice until after the song had been released, and Paul McCartney corroborated that story. John Lennon, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr

also experimented with the drug, although McCartney cautioned that

"it's easy to overestimate the influence of drugs on the Beatles'

music."

- Kary Mullis is reported to credit LSD with helping him develop DNA amplification technology, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993.

- Oliver Sacks, a neurologist

famous for writing best-selling case histories about his patients'

disorders and unusual experiences, talks about his own experiences with

LSD and other perception altering chemicals, in his book, Hallucinations.