| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Diphosphopyridine nucleotide (DPN+), Coenzyme I

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.169 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number | UU3450000 |

| UNII | |

| Properties | |

| C21H27N7O14P2 | |

| Molar mass | 663.43 g/mol |

| Appearance | White powder |

| Melting point | 160 °C (320 °F; 433 K) |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Not hazardous |

| NFPA 704 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

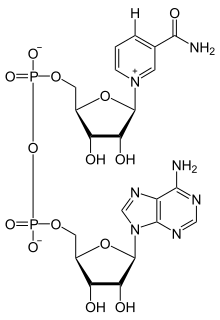

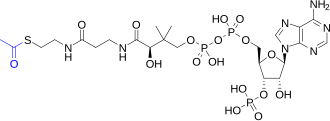

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a cofactor found in all living cells. The compound is called a dinucleotide because it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups. One nucleotide contains an adenine nucleobase and the other nicotinamide. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide exists in two forms: an oxidized and reduced form abbreviated as NAD+ and NADH respectively.

In metabolism, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide is involved in redox reactions, carrying electrons from one reaction to another. The cofactor is, therefore, found in two forms in cells: NAD+ is an oxidizing agent – it accepts electrons from other molecules and becomes reduced. This reaction forms NADH, which can then be used as a reducing agent to donate electrons. These electron transfer reactions are the main function of NAD. However, it is also used in other cellular processes, most notably a substrate of enzymes that add or remove chemical groups from proteins, in posttranslational modifications. Because of the importance of these functions, the enzymes involved in NAD metabolism are targets for drug discovery.

In organisms, NAD can be synthesized from simple building-blocks (de novo) from the amino acids tryptophan or aspartic acid. In an alternative fashion, more complex components of the coenzymes are taken up from food as niacin. Similar compounds are released by reactions that break down the structure of NAD. These preformed components then pass through a salvage pathway that recycles them back into the active form. Some NAD is converted into nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP); the chemistry of this related coenzyme is similar to that of NAD, but it has different roles in metabolism.

Although NAD+ is written with a superscript plus sign because of the formal charge on a particular nitrogen atom, at physiological pH for the most part it is actually a singly charged anion (charge of minus 1), while NADH is a doubly charged anion, because of the two bridging phosphate groups.

Physical and chemical properties

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, like all dinucleotides, consists of two nucleosides joined by a pair of bridging phosphate groups. The nucleosides each contain a ribose ring, one with adenine attached to the first carbon atom (the 1' position) and the other with nicotinamide at this position. The nicotinamide moiety can be attached in two orientations to this anomeric carbon atom. Because of these two possible structures, the compound exists as two diastereomers. It is the β-nicotinamide diastereomer of NAD+ that is found in organisms. These nucleotides are joined together by a bridge of two phosphate groups through the 5' carbons.

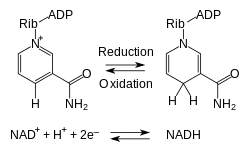

The redox reactions of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide.

In metabolism, the compound accepts or donates electrons in redox reactions. Such reactions (summarized in formula below) involve the removal of two hydrogen atoms from the reactant (R), in the form of a hydride ion (H−), and a proton (H+). The proton is released into solution, while the reductant RH2 is oxidized and NAD+ reduced to NADH by transfer of the hydride to the nicotinamide ring.

- RH2 + NAD+ → NADH + H+ + R;

From the hydride electron pair, one electron is transferred to the positively charged nitrogen of the nicotinamide ring of NAD+, and the second hydrogen atom transferred to the C4 carbon atom opposite this nitrogen. The midpoint potential of the NAD+/NADH redox pair is −0.32 volts, which makes NADH a strong reducing agent. The reaction is easily reversible, when NADH reduces another molecule and is re-oxidized to NAD+. This means the coenzyme can continuously cycle between the NAD+ and NADH forms without being consumed.

In appearance, all forms of this coenzyme are white amorphous powders that are hygroscopic and highly water-soluble. The solids are stable if stored dry and in the dark. Solutions of NAD+ are colorless and stable for about a week at 4 °C and neutral pH, but decompose rapidly in acids or alkalis. Upon decomposition, they form products that are enzyme inhibitors.

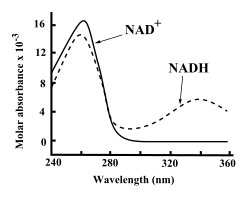

UV absorption spectra of NAD+ and NADH.

Both NAD+ and NADH strongly absorb ultraviolet light because of the adenine. For example, peak absorption of NAD+ is at a wavelength of 259 nanometers (nm), with an extinction coefficient of 16,900 M−1cm−1.

NADH also absorbs at higher wavelengths, with a second peak in UV

absorption at 339 nm with an extinction coefficient of 6,220 M−1cm−1. This difference in the ultraviolet absorption spectra

between the oxidized and reduced forms of the coenzymes at higher

wavelengths makes it simple to measure the conversion of one to another

in enzyme assays – by measuring the amount of UV absorption at 340 nm using a spectrophotometer.

NAD+ and NADH also differ in their fluorescence. NADH in solution has an emission peak at 460 nm and a fluorescence lifetime of 0.4 nanoseconds, while the oxidized form of the coenzyme does not fluoresce. The properties of the fluorescence signal changes when NADH binds to proteins, so these changes can be used to measure dissociation constants, which are useful in the study of enzyme kinetics. These changes in fluorescence are also used to measure changes in the redox state of living cells, through fluorescence microscopy.

Concentration and state in cells

In rat liver, the total amount of NAD+ and NADH is approximately 1 μmole per gram of wet weight, about 10 times the concentration of NADP+ and NADPH in the same cells. The actual concentration of NAD+ in cell cytosol is harder to measure, with recent estimates in animal cells ranging around 0.3 mM, and approximately 1.0 to 2.0 mM in yeast. However, more than 80% of NADH fluorescence in mitochondria is from bound form, so the concentration in solution is much lower.

Data for other compartments in the cell are limited, although in the mitochondrion the concentration of NAD+ is similar to that in the cytosol. This NAD+ is carried into the mitochondrion by a specific membrane transport protein, since the coenzyme cannot diffuse across membranes.

The balance between the oxidized and reduced forms of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide is called the NAD+/NADH ratio. This ratio is an important component of what is called the redox state of a cell, a measurement that reflects both the metabolic activities and the health of cells. The effects of the NAD+/NADH ratio are complex, controlling the activity of several key enzymes, including glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase. In healthy mammalian tissues, estimates of the ratio between free NAD+ and NADH in the cytoplasm typically lie around 700; the ratio is thus favourable for oxidative reactions. The ratio of total NAD+/NADH is much lower, with estimates ranging from 3–10 in mammals. In contrast, the NADP+/NADPH ratio is normally about 0.005, so NADPH is the dominant form of this coenzyme. These different ratios are key to the different metabolic roles of NADH and NADPH.

Biosynthesis

NAD+ is synthesized through two metabolic pathways. It is produced either in a de novo pathway from amino acids or in salvage pathways by recycling preformed components such as nicotinamide back to NAD+.

De novo production

Some metabolic pathways that synthesize and consume NAD+ in vertebrates. The abbreviations are defined in the text.

Most organisms synthesize NAD+ from simple components. The specific set of reactions differs among organisms, but a common feature is the generation of quinolinic acid (QA) from an amino acid—either tryptophan (Trp) in animals and some bacteria, or aspartic acid (Asp) in some bacteria and plants.

The quinolinic acid is converted to nicotinic acid mononucleotide

(NaMN) by transfer of a phosphoribose moiety. An adenylate moiety is

then transferred to form nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide (NaAD).

Finally, the nicotinic acid moiety in NaAD is amidated to a nicotinamide (Nam) moiety, forming nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide.

In a further step, some NAD+ is converted into NADP+ by NAD+ kinase, which phosphorylates NAD+. In most organisms, this enzyme uses ATP as the source of the phosphate group, although several bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and a hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii, use inorganic polyphosphate as an alternative phosphoryl donor.

Salvage pathways use three precursors for NAD+.

Salvage pathways

Besides assembling NAD+ de novo

from simple amino acid precursors, cells also salvage preformed

compounds containing a pyridine base. The three vitamin precursors used

in these salvage metabolic pathways are nicotinic acid (NA),

nicotinamide (Nam) and nicotinamide riboside (NR). These compounds can be taken up from the diet and are termed vitamin B3 or niacin. However, these compounds are also produced within cells and by digestion of cellular NAD+. Some of the enzymes involved in these salvage pathways appear to be concentrated in the cell nucleus, which may compensate for the high level of reactions that consume NAD+ in this organelle. There are some reports that mammalian cells can take up extracellular NAD+ from their surroundings, and both nicotinamide and nicotinamide riboside can be absorbed from the gut.

Despite the presence of the de novo pathway, the salvage reactions are essential in humans; a lack of niacin in the diet causes the vitamin deficiency disease pellagra. This high requirement for NAD+

results from the constant consumption of the coenzyme in reactions such

as posttranslational modifications, since the cycling of NAD+ between oxidized and reduced forms in redox reactions does not change the overall levels of the coenzyme.

The salvage pathways used in microorganisms differ from those of mammals. Some pathogens, such as the yeast Candida glabrata and the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae are NAD+ auxotrophs – they cannot synthesize NAD+ – but possess salvage pathways and thus are dependent on external sources of NAD+ or its precursors. Even more surprising is the intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis, which lacks recognizable candidates for any genes involved in the biosynthesis or salvage of both NAD+ and NADP+, and must acquire these coenzymes from its host.

Functions

Rossmann fold in part of the lactate dehydrogenase of Cryptosporidium parvum, showing NAD+ in red, beta sheets in yellow, and alpha helices in purple.

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide has several essential roles in metabolism. It acts as a coenzyme in redox reactions, as a donor of ADP-ribose moieties in ADP-ribosylation reactions, as a precursor of the second messenger molecule cyclic ADP-ribose, as well as acting as a substrate for bacterial DNA ligases and a group of enzymes called sirtuins that use NAD+ to remove acetyl groups from proteins. In addition to these metabolic functions, NAD+ emerges as an adenine nucleotide that can be released from cells spontaneously and by regulated mechanisms, and can therefore have important extracellular roles.

Oxidoreductase binding of NAD

The main role of NAD+ in metabolism is the transfer of

electrons from one molecule to another. Reactions of this type are

catalyzed by a large group of enzymes called oxidoreductases. The correct names for these enzymes contain the names of both their substrates: for example NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase catalyzes the oxidation of NADH by coenzyme Q. However, these enzymes are also referred to as dehydrogenases or reductases, with NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase commonly being called NADH dehydrogenase or sometimes coenzyme Q reductase.

There are many different superfamilies of enzymes that bind NAD+ / NADH. One of the most common superfamilies include a structural motif known as the Rossmann fold. The motif is named after Michael Rossmann who was the first scientist to notice how common this structure is within nucleotide-binding proteins.

An example of a NAD-binding bacterial enzyme involved in amino acid metabolism that does not have Rossmann fold:

In

this diagram, the hydride acceptor C4 carbon is shown at the top. When

the nicotinamide ring lies in the plane of the page with the

carboxy-amide to the right, as shown, the hydride donor lies either

"above" or "below" the plane of the page. If "above" hydride transfer is

class A, if "below" hydride transfer is class B.

When bound in the active site of an oxidoreductase, the nicotinamide

ring of the coenzyme is positioned so that it can accept a hydride from

the other substrate. Depending on the enzyme, the hydride donor is

positioned either "above" or "below" the plane of the planar C4 carbon,

as defined in the figure. Class A oxidoreductases transfer the atom from

above; class B enzymes transfer it from below. Since the C4 carbon that

accepts the hydrogen is prochiral, this can be exploited in enzyme kinetics to give information about the enzyme's mechanism. This is done by mixing an enzyme with a substrate that has deuterium atoms substituted for the hydrogens, so the enzyme will reduce NAD+ by transferring deuterium rather than hydrogen. In this case, an enzyme can produce one of two stereoisomers of NADH.

Despite the similarity in how proteins bind the two coenzymes,

enzymes almost always show a high level of specificity for either NAD+ or NADP+. This specificity reflects the distinct metabolic roles of the respective coenzymes, and is the result of distinct sets of amino acid residues in the two types of coenzyme-binding pocket. For instance, in the active site of NADP-dependent enzymes, an ionic bond is formed between a basic amino acid side-chain and the acidic phosphate group of NADP+. On the converse, in NAD-dependent enzymes the charge in this pocket is reversed, preventing NADP+ from binding. However, there are a few exceptions to this general rule, and enzymes such as aldose reductase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase can use both coenzymes in some species.

Role in redox metabolism

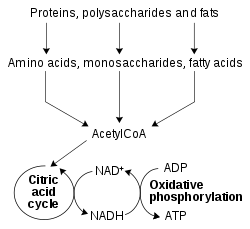

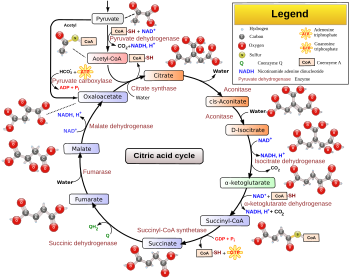

A simplified outline of redox metabolism, showing how NAD+ and NADH link the citric acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation.

The redox reactions catalyzed by oxidoreductases are vital in all

parts of metabolism, but one particularly important area where these

reactions occur is in the release of energy from nutrients. Here,

reduced compounds such as glucose and fatty acids are oxidized, thereby releasing energy. This energy is transferred to NAD+ by reduction to NADH, as part of beta oxidation, glycolysis, and the citric acid cycle. In eukaryotes the electrons carried by the NADH that is produced in the cytoplasm are transferred into the mitochondrion (to reduce mitochondrial NAD+) by mitochondrial shuttles, such as the malate-aspartate shuttle. The mitochondrial NADH is then oxidized in turn by the electron transport chain, which pumps protons across a membrane and generates ATP through oxidative phosphorylation. These shuttle systems also have the same transport function in chloroplasts.

Since both the oxidized and reduced forms of nicotinamide adenine

dinucleotide are used in these linked sets of reactions, the cell

maintains significant concentrations of both NAD+ and NADH, with the high NAD+/NADH ratio allowing this coenzyme to act as both an oxidizing and a reducing agent. In contrast, the main function of NADPH is as a reducing agent in anabolism, with this coenzyme being involved in pathways such as fatty acid synthesis and photosynthesis. Since NADPH is needed to drive redox reactions as a strong reducing agent, the NADP+/NADPH ratio is kept very low.

Although it is important in catabolism, NADH is also used in anabolic reactions, such as gluconeogenesis.

This need for NADH in anabolism poses a problem for prokaryotes growing

on nutrients that release only a small amount of energy. For example, nitrifying bacteria such as Nitrobacter

oxidize nitrite to nitrate, which releases sufficient energy to pump

protons and generate ATP, but not enough to produce NADH directly. As NADH is still needed for anabolic reactions, these bacteria use a nitrite oxidoreductase to produce enough proton-motive force to run part of the electron transport chain in reverse, generating NADH.

Non-redox roles

The coenzyme NAD+ is also consumed in ADP-ribose transfer reactions. For example, enzymes called ADP-ribosyltransferases add the ADP-ribose moiety of this molecule to proteins, in a posttranslational modification called ADP-ribosylation. ADP-ribosylation involves either the addition of a single ADP-ribose moiety, in mono-ADP-ribosylation, or the transferral of ADP-ribose to proteins in long branched chains, which is called poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation. Mono-ADP-ribosylation was first identified as the mechanism of a group of bacterial toxins, notably cholera toxin, but it is also involved in normal cell signaling. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation is carried out by the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases. The poly(ADP-ribose) structure is involved in the regulation of several cellular events and is most important in the cell nucleus, in processes such as DNA repair and telomere maintenance. In addition to these functions within the cell, a group of extracellular ADP-ribosyltransferases has recently been discovered, but their functions remain obscure.

NAD+ may also be added onto cellular RNA as a 5'-terminal modification.

The structure of cyclic ADP-ribose.

Another function of this coenzyme in cell signaling is as a precursor of cyclic ADP-ribose, which is produced from NAD+ by ADP-ribosyl cyclases, as part of a second messenger system. This molecule acts in calcium signaling by releasing calcium from intracellular stores. It does this by binding to and opening a class of calcium channels called ryanodine receptors, which are located in the membranes of organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum.

NAD+ is also consumed by sirtuins, which are NAD-dependent deacetylases, such as Sir2. These enzymes act by transferring an acetyl group from their substrate protein to the ADP-ribose moiety of NAD+;

this cleaves the coenzyme and releases nicotinamide and

O-acetyl-ADP-ribose. The sirtuins mainly seem to be involved in

regulating transcription through deacetylating histones and altering nucleosome structure.

However, non-histone proteins can be deacetylated by sirtuins as well.

These activities of sirtuins are particularly interesting because of

their importance in the regulation of aging.

Other NAD-dependent enzymes include bacterial DNA ligases, which join two DNA ends by using NAD+ as a substrate to donate an adenosine monophosphate

(AMP) moiety to the 5' phosphate of one DNA end. This intermediate is

then attacked by the 3' hydroxyl group of the other DNA end, forming a

new phosphodiester bond. This contrasts with eukaryotic DNA ligases, which use ATP to form the DNA-AMP intermediate.

Extracellular actions of NAD+

In recent years, NAD+ has also been recognized as an extracellular signaling molecule involved in cell-to-cell communication. NAD+ is released from neurons in blood vessels, urinary bladder, large intestine, from neurosecretory cells, and from brain synaptosomes, and is proposed to be a novel neurotransmitter that transmits information from nerves to effector cells in smooth muscle organs. Further studies are needed to determine the underlying mechanisms of

its extracellular actions and their importance for human health and

diseases.

Research

The enzymes that make and use NAD+ and NADH are important in both pharmacology and the research into future treatments for disease. Drug design and drug development exploits NAD+ in three ways: as a direct target of drugs, by designing enzyme inhibitors or activators based on its structure that change the activity of NAD-dependent enzymes, and by trying to inhibit NAD+ biosynthesis.

It has been studied for its potential use in the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. A placebo-controlled clinical trial in people with Parkinson's failed to show any effect.

NAD+ is also a direct target of the drug isoniazid, which is used in the treatment of tuberculosis, an infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Isoniazid is a prodrug and once it has entered the bacteria, it is activated by a peroxidase enzyme, which oxidizes the compound into a free radical form. This radical then reacts with NADH, to produce adducts that are very potent inhibitors of the enzymes enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase, and dihydrofolate reductase.

Since a large number of oxidoreductases use NAD+ and NADH as substrates, and bind them using a highly conserved structural motif, the idea that inhibitors based on NAD+ could be specific to one enzyme is surprising. However, this can be possible: for example, inhibitors based on the compounds mycophenolic acid and tiazofurin inhibit IMP dehydrogenase at the NAD+ binding site. Because of the importance of this enzyme in purine metabolism, these compounds may be useful as anti-cancer, anti-viral, or immunosuppressive drugs. Other drugs are not enzyme inhibitors, but instead activate enzymes involved in NAD+ metabolism. Sirtuins

are a particularly interesting target for such drugs, since activation

of these NAD-dependent deacetylases extends lifespan in some animal

models. Compounds such as resveratrol increase the activity of these enzymes, which may be important in their ability to delay aging in both vertebrate, and invertebrate model organisms. In one experiment, mice given NAD for one week had improved nuclear-mitochrondrial communication.

Because of the differences in the metabolic pathways of NAD+

biosynthesis between organisms, such as between bacteria and humans,

this area of metabolism is a promising area for the development of new antibiotics. For example, the enzyme nicotinamidase,

which converts nicotinamide to nicotinic acid, is a target for drug

design, as this enzyme is absent in humans but present in yeast and

bacteria.

In bacteriology, NAD, sometimes referred to factor V, is used a supplement to culture media for some fastidious bacteria.

History

Arthur Harden, co-discoverer of NAD.

The coenzyme NAD+ was first discovered by the British biochemists Arthur Harden and William John Young in 1906. They noticed that adding boiled and filtered yeast extract greatly accelerated alcoholic fermentation in unboiled yeast extracts. They called the unidentified factor responsible for this effect a coferment. Through a long and difficult purification from yeast extracts, this heat-stable factor was identified as a nucleotide sugar phosphate by Hans von Euler-Chelpin. In 1936, the German scientist Otto Heinrich Warburg

showed the function of the nucleotide coenzyme in hydride transfer and

identified the nicotinamide portion as the site of redox reactions.

Vitamin precursors of NAD+ were first identified in 1938, when Conrad Elvehjem showed that liver has an "anti-black tongue" activity in the form of nicotinamide. Then, in 1939, he provided the first strong evidence that niacin is used to synthesize NAD+. In the early 1940s, Arthur Kornberg was the first to detect an enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway. In 1949, the American biochemists Morris Friedkin and Albert L. Lehninger proved that NADH linked metabolic pathways such as the citric acid cycle with the synthesis of ATP in oxidative phosphorylation. In 1958, Jack Preiss and Philip Handler discovered the intermediates and enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of NAD+; salvage synthesis from nicotinic acid is termed the Preiss-Handler pathway. In 2004, Charles Brenner and co-workers uncovered the nicotinamide riboside kinase pathway to NAD+. Nicotinamide riboside (NR) is currently manufactured by ChromaDex under the brand name Tru Niagen.

The non-redox roles of NAD(P) were discovered later. The first to be identified was the use of NAD+ as the ADP-ribose donor in ADP-ribosylation reactions, observed in the early 1960s. Studies in the 1980s and 1990s revealed the activities of NAD+ and NADP+ metabolites in cell signaling – such as the action of cyclic ADP-ribose, which was discovered in 1987. The metabolism of NAD+ remained an area of intense research into the 21st century, with interest heightened after the discovery of the NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases called sirtuins in 2000, by Shin-ichiro Imai and coworkers.