The term Eurocentrism itself dates back to the late 1970s and became prevalent during the 1990s, especially in the context of decolonization and development and humanitarian aid offered by industrialised countries (First World) to developing countries (Third World).

Terminology

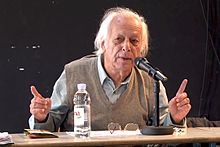

Eurocentrism as the term for an ideology was coined by Samir Amin in the 1970s

The adjective Eurocentric, or Europe-centric, has been in use, in various contexts, since at least the 1920s. The term was popularised (in French as européocentrique) in the context of decolonization and internationalism in the mid-20th century. English usage of Eurocentric as an ideological term in identity politics was current by the mid-1980s.

The abstract noun Eurocentrism (French eurocentrisme, earlier europocentrisme) as the term for an ideology was coined in the 1970s by the Egyptian Marxian economist Samir Amin, then director of the African Institute for Economic Development and Planning of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Amin used the term in the context of a global, core-periphery or dependency model of capitalist development. English usage of Eurocentrism is recorded by 1979.

The coinage of Western-centrism is younger, attested in the late 1990s, and specific to English.

European exceptionalism

During the European colonial era, encyclopedias often sought to give a rationale for the predominance of European rule during the colonial period by referring to a special position taken by Europe compared to the other continents.

Thus, Johann Heinrich Zedler, in 1741, wrote that "even though Europe is the smallest of the world's four continents,

it has for various reasons a position that places it before all

others.... Its inhabitants have excellent customs, they are courteous

and erudite in both sciences and crafts".

The Brockhaus Enzyklopädie (Conversations-Lexicon)

of 1847 still has an ostensibly Eurocentric approach and claims about

Europe that "its geographical situation and its cultural and political

significance is clearly the most important of the five continents, over

which it has gained a most influential government both in material and

even more so in cultural aspects".

European exceptionalism thus grew out of the Great Divergence of the Early Modern period,

due to the combined effects of the Scientific Revolution, the Commercial Revolution, and the rise of colonial empires, the Industrial Revolution and a Second European colonization wave.

European exceptionalism is widely reflected in popular genres of

literature, especially literature for young adults (for example, Rudyard Kipling's Kim)

and adventure literature in general. Portrayal of European colonialism

in such literature has been analysed in terms of Eurocentrism in

retrospect, such as presenting idealised and often exaggeratedly

masculine Western heroes, who conquered 'savage' peoples in the

remaining 'dark spaces' of the globe.

The European miracle, a term coined by Eric Jones in 1981,

refers to this surprising rise of Europe during the Early Modern

period. During the 15th to 18th centuries, a great divergence took

place, comprising the European Renaissance, age of discovery, the formation of the colonial empires, the Age of Reason, and the associated leap forward in technology and the development of capitalism and early industrialisation. The result was that by the 19th century, European powers dominated world trade and world politics.

Eurocentrism is a way of dominating the exchange of ideas to show

the superiority of one perspective and how much power it holds over

different social groups.

History of the concept

Anticolonialism

Even in the 19th century, anticolonial movements

had developed claims about national traditions and values that were set

against those of Europe. In some cases, as China, where local ideology

was even more exclusionist than the Eurocentric one, Westernisation

did not overwhelm longstanding Chinese attitudes to its own cultural

centrality, but some would state that idea itself is a rather desperate

attempt to cast Europe in a good light by comparison.

Orientalism developed in the late 18th century as a disproportionate Western interest in and idealization of Eastern (i.e. Asian) cultures.

By the early 20th century, some historians, such as Arnold J. Toynbee,

were attempting to construct multifocal models of world civilizations.

Toynbee also drew attention in Europe to non-European historians, such

as the medieval Tunisian scholar Ibn Khaldun. He also established links with Asian thinkers, such as through his dialogues with Daisaku Ikeda of Soka Gakkai International.

The explicit concept of Eurocentrism is a product of the period of decolonisation in the 1960s to 1970s. Its original context is the core-periphery or dependency model of capitalist development of Marxian economics (Amin 1974, 1988).

Debate since 1990s

Eurocentrism has been a particularly important concept in development studies.

Brohman (1995) argued that Eurocentrism "perpetuated intellectual

dependence on a restricted group of prestigious Western academic

institutions that determine the subject matter and methods of research".

In treatises on historical or contemporary Eurocentrism that

appeared since the 1990s, Eurocentrism is mostly cast in terms of

dualisms such as

civilized/barbaric or advanced/backward, developed/undeveloped,

core/periphery, implying "evolutionary schemas through which societies

inevitably progress", with a remnant of an "underlying presumption of a

superior white Western self as referent of analysis" (640).

Eurocentrism and the dualistic properties that it labels on

non-European countries, cultures and persons have often been criticized

in the political discourse of the 1990s and 2000s, particularly in the

greater context of political correctness, race in the United States and affirmative action.

In the 1990s, there was a trend of criticizing various geographic terms current in the English language as Eurocentric, such as

the traditional division of Eurasia into Europe and Asia or the term Middle East.

Eric Sheppard, in 2005, argued that contemporary Marxism

itself has Eurocentric traits (in spite of "Eurocentrism" originating

in the vocabulary of Marxian economics), because it supposes that the third world must go through a stage of capitalism before "progressive social formations can be envisioned".

There has been some debate on whether historical Eurocentrism

qualifies as "just another ethnocentrism", as it is found in most of the

world's cultures, especially in cultures with imperial aspirations, as

in the Sinocentrism in China; in the Empire of Japan (c. 1868-1945), or during the American Century. James M. Blaut

(2000) argued that Eurocentrism indeed army beyond other

ethnocentrisms, as the scale of European colonial expansion was

historically unprecedented and resulted in the formation of a

"colonizer's model of the world".

Race and politics in the United States

The terms Afrocentrism vs. Eurocentrism have come to play a role in the 2000s to 2010s in the context of the political discourse on race in the United States and critical whiteness studies, aiming to expose white supremacism and white privilege.

Afrocentrist scholars, such as Molefi Asante,

have argued that there is a prevalence of Eurocentric thought in the

processing of much of academia on African affairs. On the other hand, in

an article, 'Eurocentrism and Academic Imperialism' by Professor Seyed Mohammad Marandi, from the University of Tehran,

states that Eurocentric thought exists in almost all aspects of

academia in many parts of the world, especially in the humanities. Edgar Alfred Bowring

states that in the West, self-regard, self-congratulation and

denigration of the ‘Other’ run more deeply and those tendencies have

infected more aspects of their thinking, laws and policy than anywhere

else. Luke Clossey and Nicholas Guyatt have measured the degree of Eurocentrism in the research programs of top history departments. In Southern Europe and Latin America, a number of academic proposals to offer alternatives to the Eurocentric perspective have emerged, such as the project of the Epistemologies of the South by Portuguese scholar Boaventura de Sousa Santos and those of the Subaltern Studies groups in India and Latin America (the Modernity/Coloniality Group of Anibal Quijano, Edgardo Lander, Enrique Dussel, Santiago Castro-Gómez, Ramón Grosfoguel, and others.

Georg Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

(1770-1831) was the leading supporter of Eurocentrism, believing that

world history started in the East but ended in the West, especially in

Prussia's constitutional monarchy. His real interest in history was in

Europe and Oriental culture was only one episode of world history to

him. In Lectures on the Philosophy of History, he claimed that world history started in Asia but shifted to Greece and Italy, and then north of the Alps to France, Germany and England.

According to Hegel, India and China are stationary countries which lack

inner momentum. China replaced the real historically development with a

fixed, stable scenario, which makes it the outsider of world history.

Both India and China were waiting and anticipating a combination of

certain factors from outside until they can acquire real progress in

human civilization.

Hegel's ideas had a profound impact on western history. Some scholars

disagree with his ideas that the Oriental countries were outside of

world history. However, they accepted that the oriental countries were constantly in a stagnant state.

Max Weber

Max Weber

(1864-1920) was considered as the most ardent supporter of

Eurocentrism, and he suggested that capitalism is the specialty of

Europe and Oriental countries such as India and China do not contain

sufficient factors to develop capitalism. Weber wrote many treatises to publicize the distinctiveness of Europe. In The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism,

he wrote that the "rational" capitalism manifested by its enterprises

and mechanisms only appear in the Protestant western countries, and a

series of generalized and universal cultural phenomena only appear in

the west.

Even the state, with a written constitution and a government organized

by trained administrators and constrained by rational law, only appear

in the west, even though other regimes can also comprise states.

Rationality is a multi-layered term whose connotations are developed

and escalated as with the social progress. Weber regarded rationality as

a proprietary article for western capitalist society.

Andre Gunder Frank

Andre Gunder Frank

harshly criticized Eurocentrism. He believed that most scholars were

the desciples of the social sciences and history guided by Eurocentrism.

He criticized some western scholars for their ideas that non-west areas

lack outstanding contributions in history, economy, ideology, politics

and culture compared with the west.

These scholars believed that the same contribution made by the west

gives westerners an advantage of endo-genetic momentum which is pushed

towards the rest of the world, but Frank believed that the Oriental

countries also contributed to the human civilization in their own

perspectives.

Arnold Toynbee

Arnold Toynbee

(1889-1975) argued that the unit for historical research is the society

instead of the state. There are over 20 civilizations in the world

history. In his A Study of History, he gave a critical remark on

Eurocentrism. He believed that although western capitalism shrouded the

world and achieved a political unity based on its economy, the western

countries cannot "westernize" other countries.

Toynbee concluded that Eurocentrism is characteristic of three

misconceptions manifested by self-centerment, the fixed development of

Oriental countries and the linear progress.

Eurocentrism in America

Some

historians claim that American culture is largely biased in favor of a

white, male, and European context, due to the long-term influence of

European practices.

However, Western success is relatively recent, and civilizations in

different parts of the world other than Europe have made significant

contributions to the various cultures of the world, including that of

the United States.

Eurocentrism in the beauty industry

Eurocentrism

has affected the beauty realm globally. The beauty standard has become

westernized and has influenced people throughout the globe. Many have

altered their natural self to reflect this image. Many beauty and advertising companies have redirected their products to support this idea of Eurocentrism.

Clark doll experiment

In the 1940s, psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark held experiments

called “the doll tests” to examine the psychological effects of

segregation on African-American children. They tested children by

presenting them four dolls, identical but different skin tone. They had

to choose which doll they preferred and were asked the race of the doll.

Most of the children chose the white doll. The Clark's stated in their

results that the perception of the African-American children were

altered by the discrimination they faced.

The tested children also labeled positive descriptions to the white

dolls. One of the criticisms of this test is presented by Robin

Bernstein, a professor of African and African American studies and

women, gender, and sexuality. His argument is that "Clark's child

subjects by offering a new understanding of them not as psychologically

damaged dupes, but instead as agential experts in children’s culture."

Mexican doll experiment

In 2012, Mexicans recreated the doll test. Mexico’s National Council to Prevent Discrimination

presented a video where children had to pick the “good doll,” and the

doll that looks like them. By doing this experiment, the researchers

wanted to analyze the degree to which Mexican children are influenced by

modern day media accessible to them.

Most of the children chose the white doll because it was better. They

also stated that it looked like them. The people who carried out the

study noted that Euro centrism is deeply rooted in different cultures,

including Latin cultures.

There was back lash from this experiment because the children did not

have more options other than the two dolls ( black and white). The

children were half-Spanish and half-Indian descent.

Beauty advertisements

Advertisements

shown throughout the world are Eurocentric and emphasize western

characteristics. Caucasian models are the number one models to be hired

by popular, global brands like Estee Lauder and L’Oreal. Local models in

the region in Korea, Hong Kong and Japan barely made it to global

brands’ ads, compared to Caucasian models who appear in forty-four

percent of Korean and fifty-four percent of Japanese ads. By

demonstrating these ads, they are emphasizing that the ideal skin is

bright, transparent, white, full, and fine. On the other hand, dark skin

is looked down upon. Not only is skin color desired by these models, but also their physical frame, hair, and facial features.

Skin lightening

Skin lightening

has become a common practice throughout different areas of the globe in

order to fit the Eurocentric beauty standard. Many women risk their

health in order to use these products and obtain the tone they desire. A

study conducted by Dr Lamine Cissé observed the female population in

some African countries. They found that 26% of women were using skin

lightening creams at the time and 36% had used them at some time. The

common products used were hydroquinone and corticosteroids. 75% of women

who used these creams showed cutaneous adverse effects. Whitening products have also become popular in many areas in Asia like South Korea.

With the rise of these products, research has been done to study the

long term damage. Some complications experienced are exogenous

ochronosis, impaired wound healing and wound dehiscence, the fish odor

syndrome, nephropathy, steroid addiction syndrome, predisposition to

infections, a broad spectrum of cutaneous and endocrinologic

complications of corticosteroids, and suppression of

hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis. Despite all these health effects it can cause, many will not give up their products.

South Korea

South

Korea has been influenced by the Western beauty standard. In order to

achieve a more western look, some South Koreans turn to plastic surgery

to obtain those features. According to the International Society of

Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, South Korea has the highest rates of plastic

surgery procedures per capita. The most asked for procedures are the

blepharoplasty and rhinoplasty.

Another procedure done in Korea is having the muscle under the tongue

that connects to the bottom of the mouth surgically snipped. Parents

have their children to undergo this surgery in order to pronounce

English better.

In Korea, cosmetic eyelid surgery is considered to be normal. Korea has

close and modern ties with the U.S. which allows constant interaction

with the Western culture. In order to fit in they undergo these lengths

to become more westernized.

Many companies in South Korea have focused on more race-driven beauty

and have made more skin lightening products, hair straightening products

and even affordable eyelid surgeries.