At the height of the British Empire, photographs of naval and military commanders were a popular subject for eagerly collected cigarette cards. The one shown here, from the turn of the 20th century, depicts then-Captain Jellicoe (later Admiral Jellicoe of World War I) in command of HMS Centurion, the flagship of the Royal Navy's China Station.

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values.

It may also imply the glorification of the military and of the ideals

of a professional military class and the "predominance of the armed forces in the administration or policy of the state".

Militarism has been a significant element of the imperialist or expansionist ideologies of several nations throughout history. Prominent examples include the Ancient Assyrian Empire, the Greek city state of Sparta, the Roman Empire, the Aztec nation, the Kingdom of Prussia, the Habsburg/Habsburg-Lorraine Monarchies, the Ottoman Empire, the Empire of Japan, the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, the Italian Empire during the rule of Benito Mussolini, the German Empire, the British Empire, and the First French Empire under Napoleon.

By nation

Germany

Prussian (and later German) Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, right, with General Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, left, and General Albrecht von Roon,

centre. Although Bismarck was a civilian politician and not a military

officer, he wore a military uniform as part of the Prussian militarist

culture of the time. From a painting by Carl Steffeck

The roots of German militarism can be found in 19th-century Prussia and the subsequent unification of Germany under Prussian leadership. After Napoleon Bonaparte

conquered Prussia in 1806, one of the conditions of peace was that

Prussia should reduce its army to no more than 42,000 men. In order that

the country should not again be so easily conquered, the King of Prussia

enrolled the permitted number of men for one year, then dismissed that

group, and enrolled another of the same size, and so on. Thus, in the

course of ten years, he was able to gather an army of 420,000 men who

had at least one year of military training. The officers of the army

were drawn almost entirely from among the land-owning nobility.

The result was that there was gradually built up a large class of

professional officers on the one hand, and a much larger class, the rank

and file of the army, on the other. These enlisted men had become

conditioned to obey implicitly all the commands of the officers,

creating a class-based culture of deference.

This system led to several consequences. Since the officer class

also furnished most of the officials for the civil administration of the

country, the interests of the army came to be considered as identical

to the interests of the country as a whole. A second result was that the

governing class desired to continue a system which gave them so much

power over the common people, contributing to the continuing influence

of the Junker noble classes.

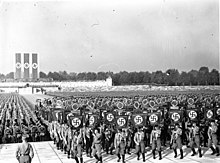

Militarism in the Third Reich

Militarism in Germany continued after World War I and the fall of the German monarchy. During the period of the Weimar Republic (1919–1933), the Kapp Putsch, an attempted coup d'état

against the republican government, was launched by disaffected members

of the armed forces. After this event, some of the more radical

militarists and nationalists were submerged in grief and despair into

the NSDAP, while more moderate elements of militarism declined. The Third Reich

was a strongly militarist state; after its fall in 1945, militarism in

German culture was dramatically reduced as a backlash against the Nazi

period.

The Federal Republic of Germany today maintains a large, modern military and has one of the highest defence budgets

in the world, although the defence budget accounts for less than 1.5

percent of Germany's GDP, is lower than e.g. that of France or Great

Britain, and does not meet the 2 percent goal,

like most other NATO members.

India

Military parade in India

The rise of militarism in India dates back to the British Raj with the establishment of several Indian independence movement organizations such as the Indian National Army led by Subhas Chandra Bose. The Indian National Army (INA) played a crucial role in pressuring the British Raj after it occupied the Andaman and Nicobar Islands with the help of Imperial Japan, but the movement lost momentum due to lack of support by the Indian National Congress, the Battle of Imphal, and Bose's sudden death.

After India gained independence in 1947, tensions with neighboring Pakistan over the Kashmir dispute and other issues led the Indian government to emphasize military preparedness (see also the political integration of India). After the Sino-Indian War in 1962, India dramatically expanded its military prowess which helped India emerge victorious during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. India became the second Asian country in the world to possess nuclear weapons, culminating in the tests of 1998. The Kashmiri insurgency and recent events including the Kargil War against Pakistan, assured that the Indian government remained committed to military expansion.

In recent years the government has increased the military

expenditure across all branches and embarked on a rapid modernization

programme.

Israel

Israel's many Arab–Israeli conflicts since the Declaration of the Establishment of the State have led to a prominence of security and defense in politics and civil society, resulting in many of Israel's former high-ranking military leaders becoming top politicians. (partial list: Yitzhak Rabin, Ariel Sharon, Ezer Weizman, Ehud Barak, Shaul Mofaz, Moshe Dayan, Yitzhak Mordechai, and Amram Mitzna).

Japan

1939 Recruitment poster for the Tank School of the Imperial Japanese Army

In parallel with 20th-century German militarism, Japanese militarism

began with a series of events by which the military gained prominence in

dictating Japan's affairs. This was evident in 15th-century Japan's Sengoku period or Age of Warring States, where powerful samurai warlords (daimyōs)

played a significant role in Japanese politics. Japan's militarism is

deeply rooted in the ancient samurai tradition, centuries before Japan's

modernization. Even though a militarist philosophy was intrinsic to the

shogunates, a nationalist style of militarism developed after the Meiji Restoration, which restored the Emperor to power and began the Empire of Japan. It is exemplified by the 1882 Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors, which called for all members of the armed forces to have an absolute personal loyalty to the Emperor.

In the 20th century (approximately in the 1920s), two factors

contributed both to the power of the military and chaos within its

ranks. One was the Cabinet Law, which required the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and Imperial Japanese Navy

(IJN) to nominate servinet could be formed. This essentially gave the

military veto power over the formation of any Cabinet in the ostensibly

parliamentary country. Another factor was gekokujō, or institutionalized disobedience by junior officers.

It was not uncommon for radical junior officers to press their goals,

to the extent of assassinating their seniors. In 1936, this phenomenon

resulted in the February 26 Incident, in which junior officers attempted a coup d'état and killed leading members of the Japanese government. The rebellion enraged Emperor Hirohito and he ordered its suppression, which was successfully carried out by loyal members of the military.

In the 1930s, the Great Depression

wrecked Japan's economy and gave radical elements within the Japanese

military the chance to realize their ambitions of conquering all of

Asia. In 1931, the Kwantung Army (a Japanese military force stationed in Manchuria) staged the Mukden Incident, which sparked the Invasion of Manchuria and its transformation into the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. Six years later, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident outside Peking sparked the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). Japanese troops streamed into China, conquering Peking, Shanghai, and the national capital of Nanking; the last conquest was followed by the Nanking Massacre. In 1940, Japan entered into an alliance with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy,

two similarly militaristic states in Europe, and advanced out of China

and into Southeast Asia. This brought about the intervention of the

United States, which embargoed all petroleum to Japan. The embargo eventually precipitated the Attack on Pearl Harbor and the entry of the U.S. into World War II.

In 1945, Japan surrendered to the United States, beginning the Occupation of Japan and the purging of all militarist influences from Japanese society and politics. In 1947, the new Constitution of Japan supplanted the Meiji Constitution

as the fundamental law of the country, replacing the rule of the

Emperor with parliamentary government. With this event, the Empire of

Japan officially came to an end and the modern State of Japan was founded.

North Korea

North Korean propaganda mural

Sŏn'gun (often transliterated "songun"), North Korea's "Military First" policy, regards military power as the highest priority of the country. This has escalated so much in the DPRK that one in five people serves in the armed forces, and the military has become one of the largest in the world.

Songun elevates the Korean People's Armed Forces within

North Korea as an organization and as a state function, granting it the

primary position in the North Korean government and society. The principle guides domestic policy and international interactions.

It provides the framework of the government, designating the military as

the "supreme repository of power". It also facilitates the

militarization of non-military sectors by emphasizing the unity of the

military and the people by spreading military culture among the masses. The North Korean government grants the Korean People's Army as the highest priority in the economy and in resource-allocation, and positions it as the model for society to emulate.

Songun is also the ideological concept behind a shift in policies (since the death of Kim Il-sung

in 1994) which emphasize the people's military over all other aspects

of state and the interests of the military comes first before the masses

(workers).

Philippines

the Philippine Army in Malolos Bulacan ca.1899

In the Pre-Colonial era, the Filipino people had their own forces, divided between the islands which each had its own ruler. They were called Sandig (Guards), Kawal (Knights), and Tanod. They also served as the police and watchers on the land, coastlines and seas. In 1521, The Visayan King of Mactan Lapu-Lapu of Cebu, organized the first recorded military action against the Spanish colonizers, in the Battle of Mactan.

In the 19th century during the Philippine Revolution, Andrés Bonifacio founded the Katipunan, a revolutionary organization against Spain at the Cry of Pugad Lawin. Some notable battles were the Siege of Baler, The Battle of Imus, Battle of Kawit, Battle of Nueva Ecija, the victorious Battle of Alapan and the famous Twin Battles of Binakayan and Dalahican. During Independence, the President General Emilio Aguinaldo established the Magdalo, a faction separate from Katipunan, and he declared the Revolutionary Government in the constitution of the First Philippine Republic.

And during the Filipino-American War, the General Antonio Luna as a High-Ranking General, He Ordered a Conscription to all Citizens, a mandatory form of National Services (at any War's) for the increase the density and the manpower of the Philippine Army.

During World War II, the Philippines was one of the participants,

as a member of Allied Forces, the Philippines with the U.S. Forces

fought the Imperial Japanese Army, (1942–1945) the notable battles is

the victorious Battle of Manila, which also called "The Liberation".

During the 1970s the President Ferdinand Marcos declared P.D.1081 or martial law, which also made the Philippines a garrison state. By the Philippine Constabulary (PC) and Integrated National Police

(INP), The High-School or Secondary and College Education have a

compulsory Curriculum concerning the Military, and nationalism which is

the "Citizens Military Training" (CMT) And "Reserve Officers Training

Corps" (ROTC).

But in 1986, when the constitution changed, this form of National

Service Training Program became non-compulsory but still part of the

Basic Education.

Turkey

Warning sign at the fence of the military area in Kırklareli, Turkey

The Ottoman Empire

lasted for centuries and always relied on its military might, but

militarism was not a part of everyday life. Militarism was only

introduced into daily life with the advent of modern institutions,

particularly schools, which became part of the state apparatus when the

Ottoman Empire was succeeded by a new nation state – the Republic of

Turkey – in 1923. The founders of the republic were determined to break

with the past and modernise the country. There was, however, an inherent

contradiction in that their modernist vision was limited by their

military roots. The leading reformers were all military men and, in

keeping with the military tradition, all believed in the authority and

the sacredness of the state. The public also believed in the military.

It was the military, after all, who led the nation through the War of Liberation (1919–1923) and saved the motherland.

The first military coup in the history of the republic was on 27th May 1960, which resulted in the hanging of PM Adnan Menderes

and 2 ministers, and a new constitution was introduced, creating a

Constitutional Court to vet the legislation passed by parliament, and a

military-dominated National Security Council to oversee the government

affairs similar to the politburo in the Soviet Union. The second military coup took place on 12th March 1971,

this time only forcing the government to resign and installing a

cabinet of technocrats and bureaucrats without dissolving the

parliament. The third military coup took place on 12th September 1980,

which resulted in the dissolution of parliament and all political

parties as well as imposition of a much more authoritarian constitution.

There was another military intervention that was called a "post-modern

coup" on 28 February 1997 which merely forced the government to resign, and finally an unsuccessful military coup attempt on 15th July 2016.

The constitutional referendums in 2010 and 2017

have changed the composition and role of the National Security Council,

and placed the armed forces under the control of civilian government.

United States

Poster shows Uncle Sam pointing his finger at the viewer in order to recruit soldiers for the American Army during World War I.

The cover of a coffee table book about the US Navy.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries political and

military leaders reformed the US federal government to establish a

stronger central government than had ever previously existed for the

purpose of enabling the nation to pursue an imperial policy in the Pacific and in the Caribbean and economic militarism

to support the development of the new industrial economy. This reform

was the result of a conflict between Neo-Hamiltonian Republicans and Jeffersonian-Jacksonian

Democrats over the proper administration of the state and direction of

its foreign policy. The conflict pitted proponents of professionalism,

based on business management principles, against those favoring more

local control in the hands of laymen and political appointees. The

outcome of this struggle, including a more professional federal civil

service and a strengthened presidency and executive branch, made a more

expansionist foreign policy possible.

After the end of the American Civil War

the national army fell into disrepair. Reforms based on various

European states including Britain, Germany, and Switzerland were made so

that it would become responsive to control from the central government,

prepared for future conflicts, and develop refined command and support

structures; these reforms led to the development of professional

military thinkers and cadre.

During this time the ideas of Social Darwinism helped propel American overseas expansion in the Pacific and Caribbean. This required modifications for a more efficient central government due to the added administration requirements (see above).

A

pie chart showing global military expenditures by country for 2018, in

US$ billions, according to the International Institute for Strategic

Studies.

The enlargement of the U.S. Army for the Spanish–American War was considered essential to the occupation and control of the new territories acquired from Spain in its defeat (Guam, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Cuba).

The previous limit by legislation of 24,000 men was expanded to 60,000

regulars in the new army bill on 2 February 1901, with allowance at that

time for expansion to 80,000 regulars by presidential discretion at

times of national emergency.

U.S. forces were again enlarged immensely for World War I. Officers such as George S. Patton were permanent captains at the start of the war and received temporary promotions to colonel.

Between the first and second world wars, the US Marine Corps engaged in questionable activities in the Banana Wars in Latin America. Retired Major General Smedley Butler,

who was at the time of his death the most decorated Marine, spoke

strongly against what he considered to be trends toward fascism and

militarism. Butler briefed Congress on what he described as a Business Plot

for a military coup, for which he had been suggested as leader; the

matter was partially corroborated, but the real threat has been

disputed. The Latin American expeditions ended with Franklin D. Roosevelt's Good Neighbor policy of 1934.

Former President Barack Obama speaking on the military intervention in Libya at the National Defense University.

After World War II, there were major cutbacks, such that units responding early in the Korean War under United Nations authority (e.g., Task Force Smith) were unprepared, resulting in catastrophic performance. It should be noted that when Harry S. Truman fired Douglas MacArthur, the tradition of civilian control held and MacArthur left without any hint of military coup.

The Cold War resulted in serious permanent military buildups. Dwight D. Eisenhower, a retired top military commander elected as a civilian President, warned, as he was leaving office, of the development of a military-industrial complex. In the Cold War, there emerged many civilian academics and industrial researchers, such as Henry Kissinger and Herman Kahn,

who had significant input into the use of military force. The

complexities of nuclear strategy and the debates surrounding them helped

produce a new group of 'defense intellectuals' and think tanks, such as

the Rand Corporation (where Kahn, among others, worked).

It has been argued that the United States has shifted to a state

of neomilitarism since the end of the Vietnam War. This form of

militarism is distinguished by the reliance on a relatively small number

of volunteer fighters; heavy reliance on complex technologies; and the

rationalization and expansion of government advertising and recruitment

programs designed to promote military service.

The direct military budget of the United States for 2008 was $740,800,000,000.

Venezuela

Hugo Chávez wearing military apparel in 2010.

Militarism in Venezuela follows the cult and myth of Simón Bolívar, known as the liberator of Venezuela. For much of the 1800s, Venezuela was ruled by powerful, militarists leaders known as caudillos. Between 1892 and 1900 alone, six rebellions occurred and 437 military actions were taken to obtain control of Venezuela. With the military controlling Venezuela for much of its history, the country practiced a "military ethos",

with civilians today still believing that military intervention in the

government is positive, especially during times of crisis, with many

Venezuelans believing that the military opens democratic opportunities

instead of blocking them.

Members of the Venezuelan armed forces carrying Chávez eyes flags saying, "Chávez lives, the fight continues".

Much of the modern political movement behind the Fifth Republic of Venezuela, ruled by the Bolivarian government established by Hugo Chávez, was built on the following of Bolívar and such militaristic ideals. Chávez often used Bolivarian propaganda to glorify the military, with Manuel Anselmi explaining in Chávez's Children: Ideology, Education, and Society in Latin America,

that "To get an idea of the importance of Bolivarian propaganda as a

source of alternative political education one can use the testimony of

Hugo Chávez himself". Chávez explained how he had "read the classics of

socialism and of military theory and study the possible role of the army

in a democratic popular revolt". In 1999 following the election of Hugo Chávez into the presidency, author Carlos Alberto Montaner described Chávez "as the new Venezuelan caudillo who would reformulate Venezuelan politics at his will".

As Chávez took power of Venezuela, his influencer, left-wing Argentine sociologist Norberto Ceresole, helped Chávez establish the Bolivarian movement in the shadow of Simón Bolívar's following, with Ceresole stating that:

All of these elements ... a military leader becoming a strong man or national head, the absence of effective, intermediary civilian institutions, the presence of an important group of "apostles" that intervene with generosity and magnanimity between the strong man and the masses ... comprise a model of change — in truth, a revolutionary model — that is absolutely new, although in line with clear historical traditions.

President Nicolás Maduro among troops during a May 2016 exercise.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute,

under the Chávez presidency between 2004 and 2008, Venezuela moved from

55th place in arms importing to 18th, acquiring nearly $2 billion worth

of weaponry from Russia. Domingo Alberto Rangel, founder of the Marxist Venezuelan political Revolutionary Left Movement,

explained that Chávez's description of a movement being "Bolivarian"

and "socialist" was contradictory, saying this "is tolerated and

continues because the regime is both military and militaristic. ...

Those who monopolize the decision in this regime are military men".

Since coming to power three years ago, Mr. Maduro has relied increasingly on the armed forces as a spiraling economic crisis pushed his approval ratings to record lows and food shortages led to lootings. ... The armed forces have swiftly repressed all opposition rallies as well as the food riots that flare up daily across the country.The Wall Street Journal

Chávez's handpicked successor, Nicolás Maduro,

relied on the military to maintain power when he was elected into

office, with Luis Manuel Esculpi, a Venezuelan security analyst, stating

that "The army is Maduro's only source of authority." Maduro grew more reliant on the military through his presidency, showing that Maduro was losing power as described by Amherst College professor, Javier Corrales.

Corrales explains that "From 2003 until Chavez died in 2013, the

civilian wing was strong, so he did not have to fall back on the

military. As civilians withdrew their support, Maduro was forced to

resort to military force." The New York Times

states that Maduro no longer had the oil revenue to buy loyalty for

protection, instead relying on favorable exchange rates, as well as the

smuggling of food and drugs, which "also generate revenue" for troops.

However, it should be noted that Venezuela denies the aggressive

use of its army , as PSUV and the Bolivarian ideology claim to be

anti-imperialist.