McDonald's Corporation is one of the most recognizable corporations in the world.

A corporation is an organization, usually a group of people or a company, authorized to act as a single entity (legally a person) and recognized as such in law. Early incorporated entities were established by charter (i.e. by an ad hoc act granted by a monarch or passed by a parliament or legislature). Most jurisdictions now allow the creation of new corporations through registration.

Corporations come in many different types but are usually divided

by the law of the jurisdiction where they are chartered into two kinds:

by whether they can issue stock or not, or by whether they are formed to make a profit or not. Corporations can be divided by the number of owners: corporation aggregate or corporation sole.

The subject of this article is a corporation aggregate. A corporation

sole is a legal entity consisting of a single ("sole") incorporated

office, occupied by a single ("sole") natural person.

Where local law distinguishes corporations by the ability to

issue stock, corporations allowed to do so are referred to as "stock

corporations", ownership of the corporation is through stock, and owners

of stock are referred to as "stockholders" or "shareholders".

Corporations not allowed to issue stock are referred to as "non-stock"

corporations; those who are considered the owners of a non-stock

corporation are persons (or other entities) who have obtained membership

in the corporation and are referred to as a "member" of the

corporation.

Corporations chartered in regions where they are distinguished by

whether they are allowed to be for profit or not are referred to as

"for profit" and "not-for-profit" corporations, respectively.

There is some overlap between stock/non-stock and

for-profit/not-for-profit in that not-for-profit corporations are always

non-stock as well. A for-profit corporation is almost always a stock

corporation, but some for-profit corporations may choose to be

non-stock. To simplify the explanation, whenever "Stockholder" or "shareholder"

is used in the rest of this article to refer to a stock corporation, it

is presumed to mean the same as "member" for a non-profit corporation

or for a profit, non-stock corporation.

Registered corporations have legal personality and their shares are owned by shareholders whose liability is generally limited to their investment. Shareholders do not typically actively manage a corporation; shareholders instead elect or appoint a board of directors to control the corporation in a fiduciary capacity. In most circumstances, a shareholder may also serve as a director or officer of a corporation.

In American English, the word corporation is most often used to describe large business corporations. In British English and in the Commonwealth countries, the term company is more widely used to describe the same sort of entity while the word corporation encompasses all incorporated entities. In American English, the word company can include entities such as partnerships that would not be referred to as companies in British English as they are not a separate legal entity.

Late in the 19th century, a new form of company having the

limited liability protections of a corporation, and the more favorable

tax treatment of either a sole proprietorship or partnership was

developed. While not a corporation, this new type of entity became very

attractive as an alternative for corporations not needing to issue

stock. In Germany, the organization was referred to as Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung or GmbH.

In the last quarter of the 20th Century this new form of non-corporate

organization became available in the United States and other countries,

and was known as the limited liability company or LLC.

Since the GmbH and LLC forms of organization are technically not

corporations (even though they have many of the same features), they

will not be discussed in this article.

History

1/8 share of the Stora Kopparberg mine, dated June 16, 1288.

The word "corporation" derives from corpus, the Latin word for body, or a "body of people". By the time of Justinian (reigned 527–565), Roman law recognized a range of corporate entities under the names universitas, corpus or collegium. These included the state itself (the Populus Romanus), municipalities, and such private associations as sponsors of a religious cult, burial clubs,

political groups, and guilds of craftsmen or traders. Such bodies

commonly had the right to own property and make contracts, to receive

gifts and legacies, to sue and be sued, and, in general, to perform

legal acts through representatives. Private associations were granted

designated privileges and liberties by the emperor.

Entities which carried on business and were the subjects of legal rights were found in ancient Rome, and the Maurya Empire in ancient India. In medieval Europe, churches became incorporated, as did local governments, such as the Pope and the City of London Corporation.

The point was that the incorporation would survive longer than the

lives of any particular member, existing in perpetuity. The alleged

oldest commercial corporation in the world, the Stora Kopparberg mining community in Falun, Sweden, obtained a charter from King Magnus Eriksson in 1347.

In medieval times, traders would do business through common law constructs, such as partnerships. Whenever people acted together with a view to profit, the law deemed that a partnership arose. Early guilds and livery companies were also often involved in the regulation of competition between traders.

Mercantilism

Replica of an East Indiaman of the Dutch East India Company/United East Indies Company. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) is often considered by many to be the first historical model of the modern corporation. The VOC was also the first permanently organized limited-liability joint-stock corporation, with a permanent capital base.

Dutch and English chartered companies, such as the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Hudson's Bay Company,

were created to lead the colonial ventures of European nations in the

17th century. Acting under a charter sanctioned by the Dutch government,

the Dutch East India Company defeated Portuguese forces and established itself in the Moluccan Islands in order to profit from the European demand for spices.

Investors in the VOC were issued paper certificates as proof of share

ownership, and were able to trade their shares on the original Amsterdam Stock Exchange. Shareholders were also explicitly granted limited liability in the company's royal charter.

A bond issued by the Dutch East India Company (VOC), dating from 1623, for the amount of 2,400 florins

In England, the government created corporations under a royal charter or an Act of Parliament with the grant of a monopoly over a specified territory. The best-known example, established in 1600, was the East India Company of London. Queen Elizabeth I granted it the exclusive right to trade with all countries to the east of the Cape of Good Hope.

Some corporations at this time would act on the government's behalf,

bringing in revenue from its exploits abroad. Subsequently, the Company

became increasingly integrated with English and later British military and colonial policy, just as most corporations were essentially dependent on the Royal Navy's ability to control trade routes.

Labeled by both contemporaries and historians as "the grandest

society of merchants in the universe", the English East India Company

would come to symbolize the dazzlingly rich potential of the

corporation, as well as new methods of business that could be both

brutal and exploitative. On 31 December 1600, Queen Elizabeth I granted the company a 15-year monopoly on trade to and from the East Indies and Africa. By 1711, shareholders in the East India Company were earning a return on their investment

of almost 150 per cent. Subsequent stock offerings demonstrated just

how lucrative the Company had become. Its first stock offering in

1713–1716 raised £418,000, its second in 1717–1722 raised £1.6 million.

A similar chartered company, the South Sea Company,

was established in 1711 to trade in the Spanish South American

colonies, but met with less success. The South Sea Company's monopoly

rights were supposedly backed by the Treaty of Utrecht, signed in 1713 as a settlement following the War of the Spanish Succession, which gave Great Britain an asiento

to trade in the region for thirty years. In fact the Spanish remained

hostile and let only one ship a year enter. Unaware of the problems,

investors in Britain, enticed by extravagant promises of profit from company promoters

bought thousands of shares. By 1717, the South Sea Company was so

wealthy (still having done no real business) that it assumed the public debt of the British government. This accelerated the inflation of the share price further, as did the Bubble Act 1720,

which (possibly with the motive of protecting the South Sea Company

from competition) prohibited the establishment of any companies without a

Royal Charter. The share price rose so rapidly that people began buying

shares merely in order to sell them at a higher price, which in turn

led to higher share prices. This was the first speculative bubble

the country had seen, but by the end of 1720, the bubble had "burst",

and the share price sank from £1000 to under £100. As bankruptcies and

recriminations ricocheted through government and high society, the mood

against corporations and errant directors was bitter.

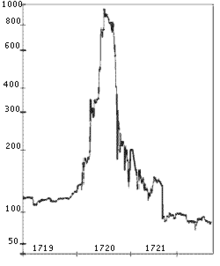

Chart of the South Sea Company's stock prices. The rapid inflation of the stock value in the 1710s led to the Bubble Act 1720, which restricted the establishment of companies without a royal charter.

In the late 18th century, Stewart Kyd, the author of the first treatise on corporate law in English, defined a corporation as

a collection of many individuals united into one body, under a special denomination, having perpetual succession under an artificial form, and vested, by policy of the law, with the capacity of acting, in several respects, as an individual, particularly of taking and granting property, of contracting obligations, and of suing and being sued, of enjoying privileges and immunities in common, and of exercising a variety of political rights, more or less extensive, according to the design of its institution, or the powers conferred upon it, either at the time of its creation, or at any subsequent period of its existence.

— A Treatise on the Law of Corporations, Stewart Kyd (1793–1794)

Development of modern company law

Due to the late 18th century abandonment of mercantilist economic theory and the rise of classical liberalism and laissez-faire economic theory due to a revolution in economics led by Adam Smith and other economists, corporations transitioned from being government or guild affiliated entities to being public and private economic entities free of governmental directions. Smith wrote in his 1776 work The Wealth of Nations

that mass corporate activity could not match private entrepreneurship,

because people in charge of others' money would not exercise as much

care as they would with their own.

Deregulation

"Jack and the Giant Joint-Stock", a cartoon in Town Talk (1858) satirizing the 'monster' joint-stock economy that came into being after the Joint Stock Companies Act 1844.

The British Bubble Act 1720's prohibition on establishing companies

remained in force until its repeal in 1825. By this point, the Industrial Revolution had gathered pace, pressing for legal change to facilitate business activity. The repeal was the beginning of a gradual lifting on restrictions, though business ventures (such as those chronicled by Charles Dickens in Martin Chuzzlewit)

under primitive companies legislation were often scams. Without

cohesive regulation, proverbial operations like the "Anglo-Bengalee

Disinterested Loan and Life Assurance Company" were undercapitalised

ventures promising no hope of success except for richly paid promoters.

The process of incorporation was possible only through a royal charter or a private act

and was limited, owing to Parliament's jealous protection of the

privileges and advantages thereby granted. As a result, many businesses

came to be operated as unincorporated associations with possibly thousands of members. Any consequent litigation

had to be carried out in the joint names of all the members and was

almost impossibly cumbersome. Though Parliament would sometimes grant a

private act to allow an individual to represent the whole in legal

proceedings, this was a narrow and necessarily costly expedient, allowed

only to established companies.

Then, in 1843, William Gladstone became the chairman of a Parliamentary Committee on Joint Stock Companies, which led to the Joint Stock Companies Act 1844, regarded as the first modern piece of company law. The Act created the Registrar of Joint Stock Companies,

empowered to register companies by a two-stage process. The first,

provisional, stage cost £5 and did not confer corporate status, which

arose after completing the second stage for another £5. For the first

time in history, it was possible for ordinary people through a simple

registration procedure to incorporate. The advantage of establishing a company as a separate legal person

was mainly administrative, as a unified entity under which the rights

and duties of all investors and managers could be channeled.

Limited liability

However,

there was still no limited liability and company members could still be

held responsible for unlimited losses by the company. The next, crucial development, then, was the Limited Liability Act 1855, passed at the behest of the then Vice President of the Board of Trade, Mr. Robert Lowe. This allowed investors to limit their liability in the event of business failure to the amount they invested in the company – shareholders were still liable directly to creditors, but just for the unpaid portion of their shares. (The principle that shareholders are liable to the corporation had been introduced in the Joint Stock Companies Act 1844).

The 1855 Act allowed limited liability to companies of more than 25 members (shareholders). Insurance companies

were excluded from the act, though it was standard practice for

insurance contracts to exclude action against individual members.

Limited liability for insurance companies was allowed by the Companies Act 1862.

This prompted the English periodical The Economist

to write in 1855 that "never, perhaps, was a change so vehemently and

generally demanded, of which the importance was so much overrated."

The major error of this judgment was recognised by the same magazine

more than 70 years later, when it claimed that, "[t]he economic

historian of the future... may be inclined to assign to the nameless

inventor of the principle of limited liability, as applied to trading

corporations, a place of honour with Watt and Stephenson, and other pioneers of the Industrial Revolution."

These two features – a simple registration procedure and limited liability – were subsequently codified into the landmark 1856 Joint Stock Companies Act.

This was subsequently consolidated with a number of other statutes in

the Companies Act 1862, which remained in force for the rest of the

century, up to and including the time of the decision in Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd.

The legislation shortly gave way to a railway boom, and from

then, the numbers of companies formed soared. In the later nineteenth

century, depression took hold, and just as company numbers had boomed,

many began to implode and fall into insolvency. Much strong academic,

legislative and judicial opinion was opposed to the notion that

businessmen could escape accountability for their role in the failing

businesses.

Further developments

Lindley LJ was the leading expert on partnerships and company law in the Salomon v. Salomon & Co. case. The landmark case confirmed the distinct corporate identity of the company.

In 1892, Germany introduced the Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung with a separate legal personality

and limited liability even if all the shares of the company were held

by only one person. This inspired other countries to introduce

corporations of this kind.

The last significant development in the history of companies was the 1897 decision of the House of Lords in Salomon v. Salomon & Co.

where the House of Lords confirmed the separate legal personality of

the company, and that the liabilities of the company were separate and

distinct from those of its owners.

In the United States, forming a corporation usually required an act of legislation until the late 19th century. Many private firms, such as Carnegie's steel company and Rockefeller's Standard Oil, avoided the corporate model for this reason (as a trust).

State governments began to adopt more permissive corporate laws from

the early 19th century, although these were all restrictive in design,

often with the intention of preventing corporations from gaining too

much wealth and power.

New Jersey was the first state to adopt an "enabling" corporate law, with the goal of attracting more business to the state,

in 1896. In 1899, Delaware followed New Jersey's lead with the

enactment of an enabling corporate statute, but Delaware only became the

leading corporate state after the enabling provisions of the 1896 New

Jersey corporate law were repealed in 1913.

The end of the 19th century saw the emergence of holding companies and corporate mergers creating larger corporations with dispersed shareholders. Countries began enacting anti-trust

laws to prevent anti-competitive practices and corporations were

granted more legal rights and protections.

The 20th century saw a proliferation of laws allowing for the creation

of corporations by registration across the world, which helped to drive

economic booms in many countries before and after World War I. Another

major post World War I shift was toward the development of conglomerates, in which large corporations purchased smaller corporations to expand their industrial base.

Starting in the 1980s, many countries with large state-owned corporations moved toward privatization, the selling of publicly owned (or 'nationalised') services and enterprises to corporations. Deregulation (reducing the regulation of corporate activity) often accompanied privatization as part of a laissez-faire policy.

Ownership and control

A corporation is, at least in theory, owned and controlled by its members. In a joint-stock company

the members are known as shareholders and each of their shares in the

ownership, control, and profits of the corporation is determined by the

portion of shares in the company that they own. Thus a person who owns a

quarter of the shares of a joint-stock company owns a quarter of the

company, is entitled to a quarter of the profit (or at least a quarter

of the profit given to shareholders as dividends) and has a quarter of

the votes capable of being cast at general meetings.

In another kind of corporation, the legal document which

established the corporation or which contains its current rules will

determine who the corporation's members are. Who a member is depends on

what kind of corporation is involved. In a worker cooperative, the members are people who work for the cooperative. In a credit union, the members are people who have accounts with the credit union.

The day-to-day activities of a corporation are typically

controlled by individuals appointed by the members. In some cases, this

will be a single individual but more commonly corporations are

controlled by a committee or by committees. Broadly speaking, there are

two kinds of committee structure.

- A single committee known as a board of directors is the method favored in most common law countries. Under this model, the board of directors is composed of both executive and non-executive directors, the latter being meant to supervise the former's management of the company.

- A two-tiered committee structure with a supervisory board and a managing board is common in civil law countries.

Formation

Historically,

corporations were created by a charter granted by government. Today,

corporations are usually registered with the state, province, or

national government and regulated by the laws enacted by that

government. Registration is the main prerequisite to the corporation's

assumption of limited liability. The law sometimes requires the

corporation to designate its principal address, as well as a registered agent (a person or company designated to receive legal service of process). It may also be required to designate an agent or other legal representative of the corporation.

Generally, a corporation files articles of incorporation

with the government, laying out the general nature of the corporation,

the amount of stock it is authorized to issue, and the names and

addresses of directors. Once the articles are approved, the

corporation's directors meet to create bylaws that govern the internal functions of the corporation, such as meeting procedures and officer positions.

The law of the jurisdiction in which a corporation operates will

regulate most of its internal activities, as well as its finances. If a

corporation operates outside its home state, it is often required to

register with other governments as a foreign corporation, and is almost always subject to laws of its host state pertaining to employment, crimes, contracts, civil actions, and the like.

Naming

Corporations

generally have a distinct name. Historically, some corporations were

named after their membership: for instance, "The President and Fellows

of Harvard College". Nowadays, corporations in most jurisdictions have a

distinct name that does not need to make reference to their membership.

In Canada, this possibility is taken to its logical extreme: many

smaller Canadian corporations have no names at all, merely numbers based

on a registration number (for example, "12345678 Ontario Limited"),

which is assigned by the provincial or territorial government where the

corporation incorporates.

In most countries, corporate names include a term or an

abbreviation that denotes the corporate status of the entity (for

example, "Incorporated" or "Inc." in the United States) or the limited

liability of its members (for example, "Limited" or "Ltd."). These terms

vary by jurisdiction and language. In some jurisdictions, they are

mandatory, and in others they are not. Their use puts everybody on constructive notice that they are dealing with an entity whose liability is limited: one can only collect from whatever assets the entity still controls when one obtains a judgment against it.

Some jurisdictions do not allow the use of the word "company" alone to denote corporate status, since the word "company" may refer to a partnership or some other form of collective ownership (in the United States it can be used by a sole proprietorship but this is not generally the case elsewhere).

Personhood

Despite not being individual human beings, corporations, as far as US law is concerned, are legal persons, and have many of the same rights and responsibilities as natural persons do. For example, a corporation can own property, and can sue or be sued. Corporations can exercise human rights against real individuals and the state, and they can themselves be responsible for human rights violations.

Corporations can be "dissolved" either by statutory operation, order of

court, or voluntary action on the part of shareholders. Insolvency

may result in a form of corporate failure, when creditors force the

liquidation and dissolution of the corporation under court order,

but it most often results in a restructuring of corporate holdings.

Corporations can even be convicted of criminal offenses, such as fraud and manslaughter. However, corporations are not considered living entities in the way that humans are.