| |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aliases | TP53, BCC7, LFS1, P53, TRP53, tumor protein p53, BMFS5 | ||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 191170 MGI: 98834 HomoloGene: 460 GeneCards: TP53 | ||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

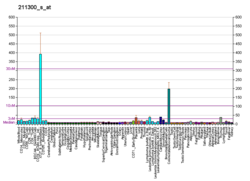

Tumor protein p53, also known as p53, cellular tumor antigen p53 (UniProt name), phosphoprotein p53, tumor suppressor p53, antigen NY-CO-13, or transformation-related protein 53 (TRP53), is any isoform of a protein encoded by homologous genes in various organisms, such as TP53 (humans) and Trp53 (mice). This homolog (originally thought to be, and often spoken of as, a single protein) is crucial in multicellular organisms, where it prevents cancer formation, thus, functions as a tumor suppressor. As such, p53 has been described as "the guardian of the genome" because of its role in conserving stability by preventing genome mutation. Hence TP53 is classified as a tumor suppressor gene. (Italics are used to denote the TP53 gene name and distinguish it from the protein it encodes.)

The name p53 was given in 1979 describing the apparent molecular mass; SDS-PAGE analysis indicates that it is a 53-kilodalton (kDa) protein. However, the actual mass of the full-length p53 protein (p53α) based on the sum of masses of the amino acid residues is only 43.7 kDa. This difference is due to the high number of proline residues in the protein, which slow its migration on SDS-PAGE, thus making it appear heavier than it actually is. In addition to the full-length protein, the human TP53 gene encodes at least 15 protein isoforms, ranging in size from 3.5 to 43.7 kDa. All these p53 proteins are called the p53 isoforms. The TP53 gene is the most frequently mutated gene (>50%) in human cancer, indicating that the TP53 gene plays a crucial role in preventing cancer formation. TP53 gene encodes proteins that bind to DNA and regulate gene expression to prevent mutations of the genome.

Gene

In humans, the TP53 gene is located on the short arm of chromosome 17 (17p13.1).

The gene spans 20 kb, with a non-coding exon 1 and a very long first

intron of 10 kb. The coding sequence contains five regions showing a

high degree of conservation in vertebrates, predominantly in exons 2, 5,

6, 7 and 8, but the sequences found in invertebrates show only distant

resemblance to mammalian TP53. TP53 orthologs have been identified in most mammals for which complete genome data are available.

In humans, a common polymorphism involves the substitution of an arginine for a proline at codon

position 72. Many studies have investigated a genetic link between this

variation and cancer susceptibility; however, the results have been

controversial. For instance, a meta-analysis from 2009 failed to show a

link for cervical cancer. A 2011 study found that the TP53 proline mutation did have a profound effect on pancreatic cancer risk among males. A study of Arab women found that proline homozygosity at TP53 codon 72 is associated with a decreased risk for breast cancer. One study suggested that TP53 codon 72 polymorphisms, MDM2 SNP309, and A2164G may collectively be associated with non-oropharyngeal cancer susceptibility and that MDM2 SNP309 in combination with TP53 codon 72 may accelerate the development of non-oropharyngeal cancer in women. A 2011 study found that TP53 codon 72 polymorphism was associated with an increased risk of lung cancer.

Meta-analyses from 2011 found no significant associations between TP53 codon 72 polymorphisms and both colorectal cancer risk and endometrial cancer risk. A 2011 study of a Brazilian birth cohort found an association between the non mutant arginine TP53 and individuals without a family history of cancer.

Another 2011 study found that the p53 homozygous (Pro/Pro) genotype was

associated with a significantly increased risk for renal cell

carcinoma.

Structure

A schematic of the known protein domains in p53. (NLS = Nuclear Localization Signal).

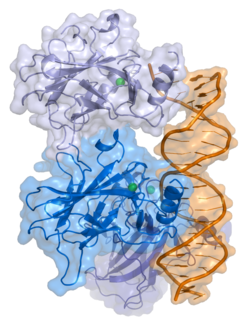

Crystal structure of four p53 DNA binding domains (as found in the bioactive homo-tetramer) and has seven domains:

- an acidic N-terminus transcription-activation domain (TAD), also known as activation domain 1 (AD1), which activates transcription factors. The N-terminus contains two complementary transcriptional activation domains, with a major one at residues 1–42 and a minor one at residues 55–75, specifically involved in the regulation of several pro-apoptotic genes.

- activation domain 2 (AD2) important for apoptotic activity: residues 43-63.

- proline rich domain important for the apoptotic activity of p53 by nuclear exportation via MAPK: residues 64-92.

- central DNA-binding core domain (DBD). Contains one zinc atom and several arginine amino acids: residues 102-292. This region is responsible for binding the p53 co-repressor LMO3.

- Nuclear Localization Signaling (NLS) domain, residues 316-325.

- homo-oligomerisation domain (OD): residues 307-355. Tetramerization is essential for the activity of p53 in vivo.

- C-terminal involved in downregulation of DNA binding of the central domain: residues 356-393.

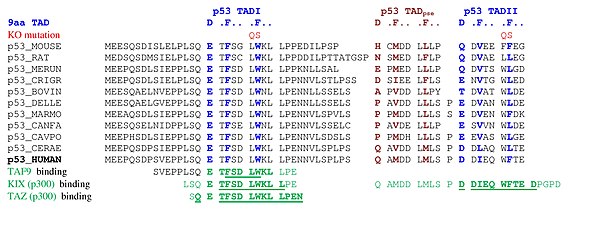

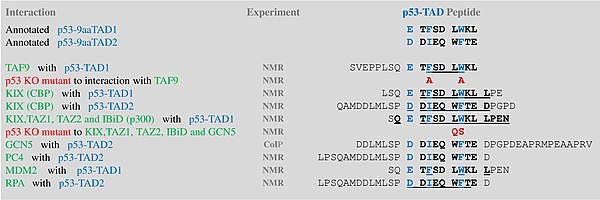

A tandem of nine-amino-acid transactivation domains (9aaTAD) was

identified in the AD1 and AD2 regions of transcription factor p53.

KO mutations and position for p53 interaction with TFIID are listed below: The competence of the p53 transactivation domains 9aaTAD to activate transcription as small peptides was reported.

9aaTADs mediate p53 interaction with general coactivators – TAF9,

CBP/p300 (all four domains KIX, TAZ1, TAZ2 and IBiD), GCN5 and PC4,

regulatory protein MDM2 and replication protein A (RPA).

Mutations that deactivate p53 in cancer usually occur in the DBD.

Most of these mutations destroy the ability of the protein to bind to

its target DNA sequences, and thus prevents transcriptional activation

of these genes. As such, mutations in the DBD are recessive loss-of-function mutations. Molecules of p53 with mutations in the OD dimerise with wild-type

p53, and prevent them from activating transcription. Therefore, OD

mutations have a dominant negative effect on the function of p53.

Wild-type p53 is a labile protein, comprising folded and unstructured regions that function in a synergistic manner.

Function

DNA damage and repair

p53 plays a role in regulation or progression through the cell cycle, apoptosis, and genomic stability by means of several mechanisms:

- It can activate DNA repair proteins when DNA has sustained damage. Thus, it may be an important factor in aging.

- It can arrest growth by holding the cell cycle at the G1/S regulation point on DNA damage recognition—if it holds the cell here for long enough, the DNA repair proteins will have time to fix the damage and the cell will be allowed to continue the cell cycle.

- It can initiate apoptosis (i.e., programmed cell death) if DNA damage proves to be irreparable.

- It is essential for the senescence response to short telomeres.

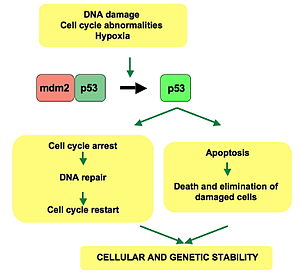

p53 pathway:

In a normal cell, p53 is inactivated by its negative regulator, mdm2.

Upon DNA damage or other stresses, various pathways will lead to the

dissociation of the p53 and mdm2 complex. Once activated, p53 will

induce a cell cycle arrest to allow either repair and survival of the

cell or apoptosis to discard the damaged cell. How p53 makes this choice

is currently unknown.

Activated p53 binds DNA and activates expression of several genes including microRNA miR-34a, WAF1/CIP1 encoding for p21 and hundreds of other down-stream genes. p21 (WAF1) binds to the G1-S/CDK (CDK4/CDK6, CDK2, and CDK1) complexes (molecules important for the G1/S transition in the cell cycle) inhibiting their activity.

When p21(WAF1) is complexed with CDK2, the cell cannot continue

to the next stage of cell division. A mutant p53 will no longer bind DNA

in an effective way, and, as a consequence, the p21 protein will not be

available to act as the "stop signal" for cell division.

Studies of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) commonly describe the

nonfunctional p53-p21 axis of the G1/S checkpoint pathway with

subsequent relevance for cell cycle regulation and the DNA damage

response (DDR). Importantly, p21 mRNA is clearly present and upregulated

after the DDR in hESCs, but p21 protein is not detectable. In this cell

type, p53 activates numerous microRNAs (like miR-302a, miR-302b, miR-302c, and miR-302d) that directly inhibit the p21 expression in hESCs.

The p21 protein binds directly to cyclin-CDK complexes that drive

forward the cell cycle and inhibits their kinase activity thereby

causing cell cycle arrest to allow repair to take place. p21 can also

mediate growth arrest associated with differentiation and a more

permanent growth arrest associated with cellular senescence. The p21

gene contains several p53 response elements that mediate direct binding

of the p53 protein, resulting in transcriptional activation of the gene

encoding the p21 protein.

The p53 and RB1 pathways are linked via p14ARF, raising the possibility that the pathways may regulate each other.

p53 expression can be stimulated by UV light, which also causes DNA damage. In this case, p53 can initiate events leading to tanning.

Stem cells

Levels of p53 play an important role in the maintenance of stem cells throughout development and the rest of human life.

In human embryonic stem cells (hESCs)s, p53 is maintained at low inactive levels. This is because activation of p53 leads to rapid differentiation of hESCs.

Studies have shown that knocking out p53 delays differentiation and

that adding p53 causes spontaneous differentiation, showing how p53

promotes differentiation of hESCs and plays a key role in cell cycle as a

differentiation regulator. When p53 becomes stabilized and activated in

hESCs, it increases p21 to establish a longer G1. This typically leads

to abolition of S-phase entry, which stops the cell cycle in G1, leading

to differentiation. p53 also activates miR-34a and miR-145, which then repress the hESCs pluripotency factors, further instigating differentiation.

In adult stem cells, p53 regulation is important for maintenance of stemness in adult stem cell niches. Mechanical signals such as hypoxia affect levels of p53 in these niche cells through the hypoxia inducible factors, HIF-1α and HIF-2α. While HIF-1α stabilizes p53, HIF-2α suppresses it.

Suppression of p53 plays important roles in cancer stem cell phenotype,

induced pluripotent stem cells and other stem cell roles and behaviors,

such as blastema formation. Cells with decreased levels of p53 have

been shown to reprogram into stem cells with a much greater efficiency

than normal cells.

Papers suggest that the lack of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis gives

more cells the chance to be reprogrammed. Decreased levels of p53 were

also shown to be a crucial aspect of blastema formation in the legs of salamanders.

p53 regulation is very important in acting as a barrier between stem

cells and a differentiated stem cell state, as well as a barrier between

stem cells being functional and being cancerous.

Other

Apart from the cellular and molecular effects above, p53 has a tissue-level anticancer effect that works by inhibiting angiogenesis.

As tumors grow they need to recruit new blood vessels to supply them,

and p53 inhibits that by (i) interfering with regulators of humor hypoxia

that also affect angiogenesis, such as HIF1 and HIF2, (ii) inhibiting

the production of angiogenic promoting factors, and (iii) directly

increasing the production of angiogenesis inhibitors, such as arresten.

p53 by regulating Leukemia Inhibitory Factor has been shown to facilitate implantation in the mouse and possibly humans reproduction.

Regulation

p53 becomes activated in response to myriad stressors, including but not limited to DNA damage (induced by either UV, IR, or chemical agents such as hydrogen peroxide), oxidative stress, osmotic shock,

ribonucleotide depletion, and deregulated oncogene expression. This

activation is marked by two major events. First, the half-life of the

p53 protein is increased drastically, leading to a quick accumulation of

p53 in stressed cells. Second, a conformational change forces p53 to be activated as a transcription regulator

in these cells. The critical event leading to the activation of p53 is

the phosphorylation of its N-terminal domain. The N-terminal

transcriptional activation domain contains a large number of

phosphorylation sites and can be considered as the primary target for

protein kinases transducing stress signals.

The protein kinases

that are known to target this transcriptional activation domain of p53

can be roughly divided into two groups. A first group of protein kinases

belongs to the MAPK

family (JNK1-3, ERK1-2, p38 MAPK), which is known to respond to several

types of stress, such as membrane damage, oxidative stress, osmotic

shock, heat shock, etc. A second group of protein kinases (ATR, ATM, CHK1 and CHK2, DNA-PK, CAK, TP53RK)

is implicated in the genome integrity checkpoint, a molecular cascade

that detects and responds to several forms of DNA damage caused by

genotoxic stress. Oncogenes also stimulate p53 activation, mediated by

the protein p14ARF.

In unstressed cells, p53 levels are kept low through a continuous degradation of p53. A protein called Mdm2 (also called HDM2 in humans), binds to p53, preventing its action and transports it from the nucleus to the cytosol. Mdm2 also acts as an ubiquitin ligase and covalently attaches ubiquitin to p53 and thus marks p53 for degradation by the proteasome. However, ubiquitylation of p53 is reversible. On activation of p53, Mdm2 is also activated, setting up a feedback loop. p53 levels can show oscillations

(or repeated pulses) in response to certain stresses, and these pulses

can be important in determining whether the cells survive the stress, or

die.

MI-63 binds to MDM2, reactivating p53 in situations where p53's function has become inhibited.

A ubiquitin specific protease, USP7 (or HAUSP), can cleave ubiquitin off p53, thereby protecting it from proteasome-dependent degradation via the ubiquitin ligase pathway . This is one means by which p53 is stabilized in response to oncogenic insults. USP42 has also been shown to deubiquitinate p53 and may be required for the ability of p53 to respond to stress.

Recent research has shown that HAUSP is mainly localized in the

nucleus, though a fraction of it can be found in the cytoplasm and

mitochondria. Overexpression of HAUSP results in p53 stabilization.

However, depletion of HAUSP does not result to a decrease in p53 levels

but rather increases p53 levels due to the fact that HAUSP binds and

deubiquitinates Mdm2. It has been shown that HAUSP is a better binding

partner to Mdm2 than p53 in unstressed cells.

USP10 however has been shown to be located in the cytoplasm in

unstressed cells and deubiquitinates cytoplasmic p53, reversing Mdm2

ubiquitination. Following DNA damage, USP10 translocates to the nucleus

and contributes to p53 stability. Also USP10 does not interact with

Mdm2.

Phosphorylation of the N-terminal end of p53 by the

above-mentioned protein kinases disrupts Mdm2-binding. Other proteins,

such as Pin1, are then recruited to p53 and induce a conformational

change in p53, which prevents Mdm2-binding even more. Phosphorylation

also allows for binding of transcriptional coactivators, like p300 and PCAF,

which then acetylate the carboxy-terminal end of p53, exposing the DNA

binding domain of p53, allowing it to activate or repress specific

genes. Deacetylase enzymes, such as Sirt1 and Sirt7, can deacetylate p53, leading to an inhibition of apoptosis. Some oncogenes can also stimulate the transcription of proteins that bind to MDM2 and inhibit its activity.

Role in disease

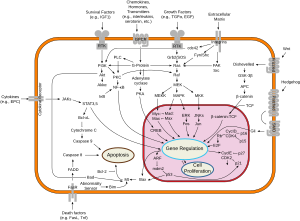

Overview of signal transduction pathways involved in apoptosis.

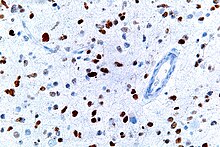

A micrograph showing cells with abnormal p53 expression (brown) in a brain tumor. p53 immunostain.

If the TP53 gene is damaged, tumor suppression is severely compromised. People who inherit only one functional copy of the TP53 gene will most likely develop tumors in early adulthood, a disorder known as Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

The TP53 gene can also be modified by mutagens (chemicals, radiation, or viruses), increasing the likelihood for uncontrolled cell division. More than 50 percent of human tumors contain a mutation or deletion of the TP53 gene. Loss of p53 creates genomic instability that most often results in an aneuploidy phenotype.

Increasing the amount of p53 may seem a solution for treatment of

tumors or prevention of their spreading. This, however, is not a usable

method of treatment, since it can cause premature aging. Restoring endogenous

normal p53 function holds some promise. Research has shown that this

restoration can lead to regression of certain cancer cells without

damaging other cells in the process. The ways by which tumor regression

occurs depends mainly on the tumor type. For example, restoration of

endogenous p53 function in lymphomas may induce apoptosis,

while cell growth may be reduced to normal levels. Thus,

pharmacological reactivation of p53 presents itself as a viable cancer

treatment option. The first commercial gene therapy, Gendicine, was approved in China in 2003 for the treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. It delivers a functional copy of the p53 gene using an engineered adenovirus.

Certain pathogens can also affect the p53 protein that the TP53 gene expresses. One such example, human papillomavirus

(HPV), encodes a protein, E6, which binds to the p53 protein and

inactivates it. This mechanism, in synergy with the inactivation of the

cell cycle regulator pRb by the HPV protein E7, allows for repeated cell division manifested clinically as warts. Certain HPV types, in particular types 16 and 18, can also lead to progression from a benign wart to low or high-grade cervical dysplasia, which are reversible forms of precancerous lesions. Persistent infection of the cervix over the years can cause irreversible changes leading to carcinoma in situ

and eventually invasive cervical cancer. This results from the effects

of HPV genes, particularly those encoding E6 and E7, which are the two

viral oncoproteins that are preferentially retained and expressed in

cervical cancers by integration of the viral DNA into the host genome.

The p53 protein is continually produced and degraded in cells of healthy people, resulting in damped oscillation.

The degradation of the p53 protein is associated with binding of MDM2.

In a negative feedback loop, MDM2 itself is induced by the p53 protein.

Mutant p53 proteins often fail to induce MDM2, causing p53 to accumulate

at very high levels. Moreover, the mutant p53 protein itself can

inhibit normal p53 protein levels. In some cases, single missense

mutations in p53 have been shown to disrupt p53 stability and function.

Suppression of p53 in human breast cancer cells is shown to lead to increased CXCR5 chemokine receptor gene expression and activated cell migration in response to chemokine CXCL13.

One study found that p53 and Myc proteins were key to the survival of Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia (CML) cells. Targeting p53 and Myc proteins with drugs gave positive results on mice with CML.

Experimental analysis of p53 mutations

Most p53 mutations are detected by DNA sequencing. However, it is

known that single missense mutations can have a large spectrum from

rather mild to very severe functional affects.

The large spectrum of cancer phenotypes due to mutations in the TP53 gene is also supported by the fact that different isoforms of p53 proteins have different cellular mechanisms for prevention against cancer. Mutations in TP53

can give rise to different isoforms, preventing their overall

functionality in different cellular mechanisms and thereby extending the

cancer phenotype from mild to severe. Recents studies show that p53

isoforms are differentially expressed in different human tissues, and

the loss-of-function or gain-of-function mutations within the isoforms can cause tissue-specific cancer or provides cancer stem cell potential in different tissues. TP53 mutation also hits energy metabolism and increases glycolysis in breast cancer cells.

The dynamics of p53 proteins, along with its antagonist Mdm2, indicate that the levels of p53, in units of concentration, oscillate as a function of time. This "damped" oscillation is both clinically documented and mathematically modelled. Mathematical models also indicate that the p53 concentration oscillates much faster once teratogens, such as double-stranded breaks (DSB) or UV radiation, are introduced to the system. This supports and models the current understanding of p53 dynamics, where DNA damage induces p53 activation. Current models can also be useful for modelling

the mutations in p53 isoforms and their effects on p53 oscillation,

thereby promoting de novo tissue-specific pharmacological drug discovery.

Discovery

p53 was identified in 1979 by Lionel Crawford, David P. Lane, Arnold Levine, and Lloyd Old, working at Imperial Cancer Research Fund (UK) Princeton University/UMDNJ (Cancer Institute of New Jersey), and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, respectively. It had been hypothesized to exist before as the target of the SV40 virus, a strain that induced development of tumors. The TP53 gene from the mouse was first cloned by Peter Chumakov of the Russian Academy of Sciences in 1982, and independently in 1983 by Moshe Oren in collaboration with David Givol (Weizmann Institute of Science). The human TP53 gene was cloned in 1984 and the full length clone in 1985.

It was initially presumed to be an oncogene due to the use of mutated cDNA following purification of tumor cell mRNA. Its role as a tumor suppressor gene was revealed in 1989 by Bert Vogelstein at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Arnold Levine at Princeton University.

Warren Maltzman, of the Waksman Institute of Rutgers University

first demonstrated that TP53 was responsive to DNA damage in the form of

ultraviolet radiation. In a series of publications in 1991–92, Michael Kastan of Johns Hopkins University, reported that TP53 was a critical part of a signal transduction pathway that helped cells respond to DNA damage.

In 1993, p53 was voted molecule of the year by Science magazine.

Isoforms

As with 95% of human genes, TP53 encodes more than one protein. In 2005 several isoforms

were discovered and until now, 12 human p53 isoforms were identified

(p53α, p53β, p53γ, ∆40p53α, ∆40p53β, ∆40p53γ, ∆133p53α, ∆133p53β,

∆133p53γ, ∆160p53α, ∆160p53β, ∆160p53γ). Furthermore, p53 isoforms are

expressed in a tissue dependent manner and p53α is never expressed

alone.

The full length p53 isoform proteins can be subdivided into different protein domains.

Starting from the N-terminus, there are first the amino-terminal

transactivation domains (TAD 1, TAD 2), which are needed to induce a

subset of p53 target genes. This domain is followed by the Proline rich

domain (PXXP), whereby the motif PXXP is repeated (P is a Proline and X

can be any amino acid). It is required among others for p53 mediated apoptosis.

Some isoforms lack the Proline rich domain, such as Δ133p53β,γ and

Δ160p53α,β,γ; hence some isoforms of p53 are not mediating apoptosis,

emphasizing the diversifying roles of the TP53 gene. Afterwards there is the DNA binding domain (DBD), which enables the proteins to sequence specific binding. The carboxyl terminal

domain completes the protein. It includes the nuclear localization

signal (NLS), the nuclear export signal (NES) and the oligomerisation

domain (OD). The NLS and NES are responsible for the subcellular

regulation of p53. Through the OD, p53 can form a tetramer and then bind

to DNA. Among the isoforms, some domains can be missing, but all of

them share most of the highly conserved DNA-binding domain.

The isoforms are formed by different mechanisms. The beta and the

gamma isoforms are generated by multiple splicing of intron 9, which

leads to a different C-terminus. Furthermore, the usage of an internal

promoter in intron 4 causes the ∆133 and ∆160 isoforms, which lack the

TAD domain and a part of the DBD. Moreover, alternative initiation of

translation at codon 40 or 160 bear the ∆40p53 and ∆160p53 isoforms.

Due to the isoformic nature of p53 proteins, there have been several sources of evidence showing that mutations within the TP53

gene giving rise to mutated isoforms are causative agents of various

cancer phenotypes, from mild to severe, due to single mutation in the TP53 gene.