A patent is a form of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, selling, and importing an invention for a limited period of years, in exchange for publishing an enabling public disclosure of the invention. In most countries patent rights fall under civil law and the patent holder needs to sue someone infringing the patent in order to enforce his or her rights. In some industries patents are an essential form of competitive advantage; in others they are irrelevant.

The procedure for granting patents, requirements placed on the

patentee, and the extent of the exclusive rights vary widely between

countries according to national laws and international agreements.

Typically, however, a patent application must include one or more claims

that define the invention. A patent may include many claims, each of

which defines a specific property right. These claims must meet relevant

patentability requirements, such as novelty, usefulness, and non-obviousness.

Under the World Trade Organization's (WTO) TRIPS Agreement,

patents should be available in WTO member states for any invention, in

all fields of technology, provided they are new, involve an inventive

step, and are capable of industrial application. Nevertheless, there are variations on what is patentable subject matter from country to country, also among WTO member states. TRIPS also provides that the term of protection available should be a minimum of twenty years.

Definition

The word patent originates from the Latin patere, which means "to lay open" (i.e., to make available for public inspection). It is a shortened version of the term letters patent,

which was an open document or instrument issued by a monarch or

government granting exclusive rights to a person, predating the modern

patent system. Similar grants included land patents, which were land grants by early state governments in the USA, and printing patents, a precursor of modern copyright.

In modern usage, the term patent usually refers to the

right granted to anyone who invents something new, useful and

non-obvious. Some other types of intellectual property rights are also

called patents in some jurisdictions: industrial design rights are called design patents in the US, plant breeders' rights are sometimes called plant patents, and utility models and Gebrauchsmuster are sometimes called petty patents or innovation patents.

The additional qualification utility patent is sometimes

used (primarily in the US) to distinguish the primary meaning from these

other types of patents. Particular species of patents for inventions

include biological patents, business method patents, chemical patents and software patents.

History

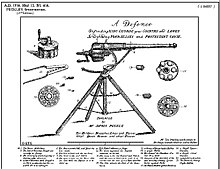

The Venetian Patent Statute, issued by the Senate of Venice in 1474, and one of the earliest statutory patent systems in the world.

Although there is some evidence that some form of patent rights was recognized in Ancient Greece in the Greek city of Sybaris, the first statutory patent system is generally regarded to be the Venetian Patent Statute of 1474. Patents were systematically granted in Venice as of 1474, where they issued a decree by which new and inventive devices had to be communicated to the Republic in order to obtain legal protection against potential infringers. The period of protection was 10 years.

As Venetians emigrated, they sought similar patent protection in their

new homes. This led to the diffusion of patent systems to other

countries.

The English patent system evolved from its early medieval origins

into the first modern patent system that recognised intellectual

property in order to stimulate invention; this was the crucial legal

foundation upon which the Industrial Revolution could emerge and flourish. By the 16th century, the English Crown would habitually abuse the granting of letters patent for monopolies. After public outcry, King James I of England (VI of Scotland)

was forced to revoke all existing monopolies and declare that they were

only to be used for "projects of new invention". This was incorporated

into the Statute of Monopolies

(1624) in which Parliament restricted the Crown's power explicitly so

that the King could only issue letters patent to the inventors or

introducers of original inventions for a fixed number of years. The

Statute became the foundation for later developments in patent law in

England and elsewhere.

James Puckle's 1718 early autocannon was one of the first inventions required to provide a specification for a patent.

Important developments in patent law emerged during the 18th century

through a slow process of judicial interpretation of the law. During the

reign of Queen Anne,

patent applications were required to supply a complete specification of

the principles of operation of the invention for public access. Legal battles around the 1796 patent taken out by James Watt for his steam engine,

established the principles that patents could be issued for

improvements of an already existing machine and that ideas or principles

without specific practical application could also legally be patented. Influenced by the philosophy of John Locke,

the granting of patents began to be viewed as a form of intellectual

property right, rather than simply the obtaining of economic privilege.

The English legal system became the foundation for patent law in countries with a common law heritage, including the United States, New Zealand and Australia. In the Thirteen Colonies, inventors could obtain patents through petition to a given colony's legislature. In 1641, Samuel Winslow was granted the first patent in North America by the Massachusetts General Court for a new process for making salt.

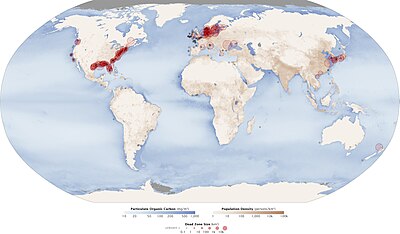

U.S. patents granted, 1790–2010.

The modern French patent system was created during the Revolution in 1791.

Patents were granted without examination since inventor's right was

considered as a natural one. Patent costs were very high (from 500 to

1,500 francs). Importation patents protected new devices coming from

foreign countries. The patent law was revised in 1844 - patent cost was

lowered and importation patents were abolished.

The first Patent Act of the U.S. Congress was passed on April 10, 1790, titled "An Act to promote the progress of useful Arts". The first patent under the Act was granted on July 31, 1790 to Samuel Hopkins for a method of producing potash

(potassium carbonate). A revised patent law was passed in 1793, and in

1836 a major revision to the patent law was passed. The 1836 law

instituted a significantly more rigorous application process, including

the establishment of an examination system. Between 1790 and 1836 about

ten thousand patents were granted. By the American Civil War about 80,000 patents had been granted.

Law

Effects

A patent does not give a right to make or use or sell an invention. Rather, a patent provides, from a legal standpoint, the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, offering for sale, or importing the patented invention for the term of the patent, which is usually 20 years from the filing date subject to the payment of maintenance fees.

From an economic and practical standpoint however, a patent is better

and perhaps more precisely regarded as conferring upon its proprietor "a

right to try to exclude by asserting the patent in court", for

many granted patents turn out to be invalid once their proprietors

attempt to assert them in court.

A patent is a limited property right the government gives inventors in

exchange for their agreement to share details of their inventions with

the public. Like any other property right, it may be sold, licensed, mortgaged, assigned or transferred, given away, or simply abandoned.

A patent, being an exclusionary right, does not necessarily give

the patent owner the right to exploit the invention subject to the

patent. For example, many inventions are improvements of prior

inventions that may still be covered by someone else's patent.

If an inventor obtains a patent on improvements to an existing

invention which is still under patent, they can only legally use the

improved invention if the patent holder of the original invention gives

permission, which they may refuse.

Some countries have "working provisions" that require the

invention be exploited in the jurisdiction it covers. Consequences of

not working an invention vary from one country to another, ranging from

revocation of the patent rights to the awarding of a compulsory license

awarded by the courts to a party wishing to exploit a patented

invention. The patentee has the opportunity to challenge the revocation

or license, but is usually required to provide evidence that the

reasonable requirements of the public have been met by the working of

invention.

Challenges

In most jurisdictions, there are ways for third parties to challenge the

validity of an allowed or issued patent at the national patent office;

these are called opposition proceedings.

It is also possible to challenge the validity of a patent in court. In

either case, the challenging party tries to prove that the patent

should never have been granted. There are several grounds for

challenges: the claimed subject matter is not patentable subject matter

at all; the claimed subject matter was actually not new, or was

obvious to experts in the field, at the time the application was filed;

or that some kind of fraud was committed during prosecution with regard

to listing of inventors, representations about when discoveries were

made, etc. Patents can be found to be invalid in whole or in part for

any of these reasons.

Infringement

Patent infringement occurs when a third party, without authorization

from the patentee, makes, uses, or sells a patented invention. Patents,

however, are enforced on a nation by nation basis. The making of an item

in China, for example, that would infringe a U.S. patent, would not

constitute infringement under US patent law unless the item were

imported into the U.S.

Enforcement

Patents can generally only be enforced through civil lawsuits

(for example, for a U.S. patent, by an action for patent infringement

in a United States federal court), although some countries (such as France and Austria) have criminal penalties for wanton infringement. Typically, the patent owner seeks monetary compensation for past infringement, and seeks an injunction

that prohibits the defendant from engaging in future acts of

infringement. To prove infringement, the patent owner must establish

that the accused infringer practises all the requirements of at least

one of the claims of the patent. (In many jurisdictions the scope of the

patent may not be limited to what is literally stated in the claims,

for example due to the doctrine of equivalents).

An accused infringer has the right to challenge the validity of the patent allegedly being infringed in a counterclaim.

A patent can be found invalid on grounds described in the relevant

patent laws, which vary between countries. Often, the grounds are a

subset of requirements for patentability in the relevant country. Although an infringer is generally free to rely on any available ground of invalidity (such as a prior publication, for example), some countries have sanctions to prevent the same validity questions being relitigated. An example is the UK Certificate of contested validity.

Patent licensing agreements are contracts

in which the patent owner (the licensor) agrees to grant the licensee

the right to make, use, sell, and/or import the claimed invention,

usually in return for a royalty or other compensation. It is common for

companies engaged in complex technical fields to enter into multiple

license agreements associated with the production of a single product.

Moreover, it is equally common for competitors in such fields to license

patents to each other under cross-licensing agreements in order to share the benefits of using each other's patented inventions.

Ownership

In

most countries, both natural persons and corporate entities may apply

for a patent. In the United States, however, only the inventor(s) may

apply for a patent although it may be assigned to a corporate entity subsequently

and inventors may be required to assign inventions to their employers

under an employment contract. In most European countries, ownership of

an invention may pass from the inventor to their employer by rule of law

if the invention was made in the course of the inventor's normal or

specifically assigned employment duties, where an invention might

reasonably be expected to result from carrying out those duties, or if

the inventor had a special obligation to further the interests of the

employer's company.

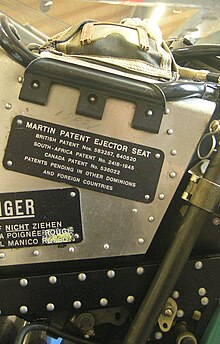

The plate of the Martin ejector seat

of a military aircraft, stating that the product is covered by multiple

patents in the UK, South Africa, Canada and pending in "other"

jurisdictions. Dübendorf Museum of Military Aviation.

The inventors, their successors or their assignees become the

proprietors of the patent when and if it is granted. If a patent is

granted to more than one proprietor, the laws of the country in question

and any agreement between the proprietors may affect the extent to

which each proprietor can exploit the patent. For example, in some

countries, each proprietor may freely license or assign their rights in

the patent to another person while the law in other countries prohibits

such actions without the permission of the other proprietor(s).

The ability to assign ownership rights increases the liquidity of a patent as property. Inventors can obtain patents and then sell them to third parties.

The third parties then own the patents and have the same rights to

prevent others from exploiting the claimed inventions, as if they had

originally made the inventions themselves.

Governing laws

The grant and enforcement of patents are governed by national laws,

and also by international treaties, where those treaties have been given

effect in national laws. Patents are granted by national or regional

patent offices.

A given patent is therefore only useful for protecting an invention in

the country in which that patent is granted. In other words, patent law

is territorial in nature. When a patent application is published, the

invention disclosed in the application becomes prior art and enters the public domain

(if not protected by other patents) in countries where a patent

applicant does not seek protection, the application thus generally

becoming prior art against anyone (including the applicant) who might

seek patent protection for the invention in those countries.

Commonly, a nation or a group of nations forms a patent office

with responsibility for operating that nation's patent system, within

the relevant patent laws. The patent office generally has responsibility

for the grant of patents, with infringement being the remit of national

courts.

The authority for patent statutes in different countries varies.

In the UK, substantive patent law is contained in the Patents Act 1977

as amended. In the United States, the Constitution empowers Congress to make laws to "promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts..." The laws Congress passed are codified in Title 35 of the United States Code and created the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

There is a trend towards global harmonization of patent laws, with the World Trade Organization (WTO) being particularly active in this area. The TRIPS Agreement

has been largely successful in providing a forum for nations to agree

on an aligned set of patent laws. Conformity with the TRIPS agreement

is a requirement of admission to the WTO and so compliance is seen by

many nations as important. This has also led to many developing

nations, which may historically have developed different laws to aid

their development, enforcing patents laws in line with global practice.

Internationally, there are international treaty procedures, such as the procedures under the European Patent Convention (EPC) [constituting the European Patent Organisation

(EPOrg)], that centralize some portion of the filing and examination

procedure. Similar arrangements exist among the member states of ARIPO and OAPI, the analogous treaties among African countries, and the nine CIS member states that have formed the Eurasian Patent Organization. A key international convention relating to patents is the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property,

initially signed in 1883. The Paris Convention sets out a range of

basic rules relating to patents, and although the convention does not

have direct legal effect in all national jurisdictions, the principles

of the convention are incorporated into all notable current patent

systems. The most significant aspect of the convention is the provision

of the right to claim priority:

filing an application in any one member state of the Paris Convention

preserves the right for one year to file in any other member state, and

receive the benefit of the original filing date. Another key treaty is

the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization

(WIPO) and covering more than 150 countries. The Patent Cooperation

Treaty provides a unified procedure for filing patent applications to

protect inventions in each of its contracting states. A patent

application filed under the PCT is called an international application,

or PCT application.

Application and prosecution

A patent is requested by filing a written application

at the relevant patent office. The person or company filing the

application is referred to as "the applicant". The applicant may be the

inventor or its assignee. The application contains a description of how

to make and use the invention that must provide sufficient detail

for a person skilled in the art (i.e., the relevant area of technology)

to make and use the invention. In some countries there are requirements

for providing specific information such as the usefulness of the

invention, the best mode

of performing the invention known to the inventor, or the technical

problem or problems solved by the invention. Drawings illustrating the

invention may also be provided.

The application also includes one or more claims that define what a patent covers or the "scope of protection".

After filing, an application is often referred to as "patent pending".

While this term does not confer legal protection, and a patent cannot

be enforced until granted, it serves to provide warning to potential

infringers that if the patent is issued, they may be liable for damages.

Once filed, a patent application is "prosecuted". A patent examiner reviews the patent application to determine if it meets the patentability requirements of that country. If the application does not comply, objections are communicated to the applicant or their patent agent or attorney through an Office action,

to which the applicant may respond. The number of Office actions and

responses that may occur vary from country to country, but eventually a

final rejection is sent by the patent office, or the patent application

is granted, which after the payment of additional fees, leads to an

issued, enforceable patent. In some jurisdictions, there are

opportunities for third parties to bring an opposition proceeding between grant and issuance, or post-issuance.

Once granted the patent is subject in most countries to renewal fees

to keep the patent in force. These fees are generally payable on a

yearly basis. Some countries or regional patent offices (e.g. the European Patent Office) also require annual renewal fees to be paid for a patent application before it is granted.

Costs

The costs

of preparing and filing a patent application, prosecuting it until grant

and maintaining the patent vary from one jurisdiction to another, and

may also be dependent upon the type and complexity of the invention, and

on the type of patent.

The European Patent Office estimated in 2005 that the average

cost of obtaining a European patent (via a Euro-direct application, i.e.

not based on a PCT application) and maintaining the patent for a

10-year term was around €32,000. Since the London Agreement entered into force on May 1, 2008, this estimation is however no longer up-to-date, since fewer translations are required.

In the United States, in 2000 the cost of obtaining a patent (patent prosecution) was estimated to be from $10,000 to $30,000 per patent.

When patent litigation is involved (which in year 1999 happened in

about 1,600 cases compared to 153,000 patents issued in the same year), costs increase significantly: although 95% of patent litigation cases are settled out of court,

those that reach the courts have legal costs on the order of a million

dollars per case, not including associated business costs.

Alternatives

A defensive publication is the act of publishing a detailed description of a new invention without patenting it, so as to establish prior art

and public identification as the creator/originator of an invention,

although a defensive publication can also be anonymous. A defensive

publication prevents others from later being able to patent the

invention.

A trade secret

is information that is intentionally kept confidential and that

provides a competitive advantage to its possessor. Trade secrets are

protected by non-disclosure agreement and labour law, each of which prevents information leaks such as breaches of confidentiality and industrial espionage. Compared to patents, the advantages of trade secrets are that the value of a trade secret continues until it is made public,

whereas a patent is only in force for a specified time, after which

others may freely copy the invention; does not require payment of fees

to governmental agencies or filing paperwork; has an immediate effect; and does not require any disclosure of information to the public. The key disadvantage of a trade secret is its vulnerability to reverse engineering.

Benefits

Primary

incentives embodied in the patent system include incentives to invent

in the first place; to disclose the invention once made; to invest the

sums necessary to experiment, produce and market the invention; and to design around and improve upon earlier patents.

- Patents provide incentives for economically efficient research and development (R&D). A study conducted annually by the Institute for Prospective Technological Studies (IPTS) shows that the 2,000 largest global companies invested more than 430 billion euros in 2008 in their R&D departments. If the investments can be considered as inputs of R&D, real products and patents are the outputs. Based on these groups, a project named Corporate Invention Board, had measured and analyzed the patent portfolios to produce an original picture of their technological profiles. Supporters of patents argue that without patent protection, R&D spending would be significantly less or eliminated altogether, limiting the possibility of technological advances or breakthroughs. Corporations would be much more conservative about the R&D investments they made, as third parties would be free to exploit any developments. This second justification is closely related to the basic ideas underlying traditional property rights. Specifically, "[t]he patent internalizes the externality by giving the [inventor] a property right over its invention." A 2008 study by Yi Quan of Kellogg School of Management showed that countries instituting patent protection on pharmaceuticals did not necessarily have an increase in domestic pharmaceutical innovation. Only countries with "higher levels of economic development, educational attainment, and economic freedom" showed an increase. There also appeared to be an optimal level of patent protection that increased domestic innovation.

- In accordance with the original definition of the term "patent", patents are intended to facilitate and encourage disclosure of innovations into the public domain for the common good. Thus patenting can be viewed as contributing to open hardware after an embargo period (usually of 20 years). If inventors did not have the legal protection of patents, in many cases, they might prefer or tend to keep their inventions secret (e.g. keep trade secrets). Awarding patents generally makes the details of new technology publicly available, for exploitation by anyone after the patent expires, or for further improvement by other inventors. Furthermore, when a patent's term has expired, the public record ensures that the patentee's invention is not lost to humanity.

- In many industries (especially those with high fixed costs and either low marginal costs or low reverse engineering costs — computer processors, and pharmaceuticals for example), once an invention exists, the cost of commercialization (testing, tooling up a factory, developing a market, etc.) is far more than the initial conception cost. (For example, the internal rule of thumb at several computer companies in the 1980s was that post-R&D costs were 7-to-1.)

One effect of modern patent usage is that a small-time inventor, who

can afford both the patenting process and the defense of the patent,

can use the exclusive right status to become a licensor. This allows

the inventor to accumulate capital from licensing the invention and may

allow innovation to occur because he or she may choose not to manage a

manufacturing buildup for the invention. Thus the inventor's time and

energy can be spent on pure innovation, allowing others to concentrate

on manufacturability.

Another effect of modern patent usage is to both enable and incentivize competitors to design around (or to "invent around" according to R S Praveen Raj) the patented invention. This may promote healthy competition among manufacturers, resulting in gradual improvements of the technology base. This may help augment national economies and confer better living standards to the citizens. The 1970 Indian Patent Act

allowed the Indian pharmaceutical industry to develop local

technological capabilities in this industry. This act coincided with the

transformation of India from a bulk importer of pharmaceutical drugs to

a leading exporter.

The rapid evolution of Indian pharmaceutical industry since the

mid-1970s highlights the fact that the design of the patent act was

instrumental in building local capabilities even in a developing country

like India.

This was possible because for many years prior to its membership in the

World Trade Organization (WTO), India did not recognize product patents

for pharmaceuticals. Without product patents with which to contend,

Indian pharmaceutical companies were able to churn out countless generic

drugs, establishing India as one of the leading generic drug

manufacturers in the world. Yet in 2005, because of its obligations

under the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property

Rights (TRIPS), India was compelled to amend its laws to provide product

patent protection to pharmaceuticals. In an attempt to satisfy the

competing demands for inexpensive drugs and effective intellectual

property protection, the Indian government created a law that afforded

protection to pharmaceuticals only if they constituted brand new

chemical substances or enhanced the therapeutic “efficacy” of known

substances. This law, which is codified under section 3(d) of the

Patents (Amendment) Act of 2005,7 has not sat well with some MNCs, including the Swiss company Novartis.

Following the denial of a patent for its leukemia drug, Glivec,

Novartis challenged the validity of section 3(d) under TRIPS and the

Indian Constitution. The Indian Supreme Court ruled against Novartis in a

decision that has, and will continue to have, broad implications for

MNCs, the Indian pharmaceutical industry, and people around the world in

need of affordable drugs.

Criticism

Legal scholars, economists, activists, policymakers, industries, and

trade organizations have held differing views on patents and engaged in

contentious debates on the subject. Critical perspectives emerged in the

nineteenth century that were especially based on the principles of free trade.

Contemporary criticisms have echoed those arguments, claiming that

patents block innovation and waste resources (e.g. with patent-related overheads) that could otherwise be used productively to improve technology. These and other research findings that patents decreased innovation because of the following mechanisms:

- Low quality, already known or obvious patents hamper innovation and commercialization.

- Blocking the use of fundamental knowledge with patents creates a "tragedy of the anticommons, where future innovations can not take place outside of a single firm in an entire field.

- Patents weaken the public domain and innovation that comes from it.

- Patent thickets, or "an overlapping set of patent rights", in particular slow innovation.

- Broad patents prevent companies from commercializing products and hurt innovation. In the worst case, such broad patents are held by non-practicing entities (patent trolls), which do not contribute to innovation. Enforcement by patent trolls of poor quality patents has led to criticism of the patent office as well as the system itself. For example, in 2011, United States business entities incurred $29 billion in direct costs because of patent trolls. Lawsuits brought by "patent assertion companies" made up 61% of all patent cases in 2012, according to the Santa Clara University School of Law.

- Patents apply a "one size fits all" model to industries with differing needs, that is especially unproductive for the software industry.

- Rent-seeking by owners of pharmaceutical patents have also been a particular focus of criticism, as the high prices they enable puts life-saving drugs out of reach of many people.

Boldrin and Levine conclude "Our preferred policy solution is to

abolish patents entirely and to find other legislative instruments, less

open to lobbying and rent seeking, to foster innovation when there is

clear evidence that laissez-faire undersupplies it." Abolishing patents may be politically challenging in some countries,

however, as the primary economic theories supporting patent law hold

that inventors and innovators need patents to recoup the costs

associated with research, inventing, and commercializing; this reasoning is weakened if the new technologies decrease these costs. A 2016 paper argued for substantial weakening of patents because current technologies (e.g. 3D printing, cloud computing, synthetic biology, etc.) have reduced the cost of innovation.

Debates over the usefulness of patents for their primary objective are part of a larger discourse on intellectual property protection, which also reflects differing perspectives on copyright.

Anti-patent initiatives

- The Patent Busting Project is an Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) initiative challenging patents that the organization claims are illegitimate and suppress innovation or limit online expression. The initiative launched in 2004 and involves two phases: documenting the damage caused by these patents, and submitting challenges to the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

- Patent critic, Joseph Stiglitz has proposed Prizes as an alternative to patents in order to further advance solutions to global problems such as AIDS.

- In 2012, Stack Exchange launched Ask Patents, a forum for crowdsourcing prior art to invalidate patents.

- Several authors have argued for developing defensive prior art to prevent patenting based on obviousness using lists or algorithms.[84] For example, a Professor of Law at the University of North Carolina School of Law, has demonstrated a method to protect DNA research., which could apply to other technology. Chin wrote an algorithm to generate 11 million "obvious" nucleotide sequences to count as prior art and his algorithmic approach has already proven effective at anticipating prior art against oligonucleotide composition claims filed since his publication of the list and has been cited by the U.S. patent office a number of times. More recently, Joshua Pearce developed an open-source algorithm for identifying prior art for 3D printing materials to make such materials obvious by patent standards. As the 3-D printing community is already grappling with legal issues, this development was hotly debated in the technical press. Chin made the same algorithem-based obvious argument in DNA probes.

- Google and other technology companies founded the LOT Network in 2014 to combat patent assertion entities by cross-licensing patents, thereby preventing legal action by such entities.