| Behaviour therapy | |

|---|---|

| ICD-9-CM | 94.33 |

| MeSH | D001521 |

Behavior therapy or behavioral psychotherapy is a broad term referring to clinical psychotherapy that uses techniques derived from behaviorism. Those who practice behavior therapy tend to look at specific, learned behaviors and how the environment influences those behaviors. Those who practice behavior therapy are called behaviourists, or behavior analysts. They tend to look for treatment outcomes that are objectively measurable. Behavior therapy does not involve one specific method but it has a wide range of techniques that can be used to treat a person's psychological problems. Traditional behavior therapy draws from respondent conditioning and operant conditioning to solve patients problems.

Behavioral psychotherapy is sometimes juxtaposed with cognitive psychotherapy, while cognitive behavioral therapy integrates aspects of both approaches.

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) is the application of behavior analysis that focuses on assessing how environmental variables influence learning principles, particularly respondent and operant conditioning, to identify potential behavior-change procedures, which are frequently used throughout clinical therapy. Cognitive-behavior therapy views cognition and emotions as preceding overt behavior with treatment plans in psychotherapy to lessen the issue. Hallmark techniques of behaviour therapies are overlapping components of cognitive psychology, in addition to behaviour analytic principles of counterconditioning, punishment, habituation, and functional analysis (FA).

History

Precursors of certain fundamental aspects of behaviour therapy have

been identified in various ancient philosophical traditions,

particularly Stoicism. For example, Wolpe and Lazarus wrote,

While the modern behavior therapist deliberately applies principles of learning to this therapeutic operations, empirical behavior therapy is probably as old as civilization – if we consider civilization as having started when man first did things to further the well-being of other men. From the time that this became a feature of human life there must have been occasions when a man complained of his ills to another who advised or persuaded him of a course of action. In a broad sense, this could be called behavior therapy whenever the behavior itself was conceived as the therapeutic agent. Ancient writings contain innumerable behavioral prescriptions that accord with this broad conception of behavior therapy.

The first use of the term behaviour modification appears to have been by Edward Thorndike in 1911. His article Provisional Laws of Acquired Behavior or Learning makes frequent use of the term "modifying behavior". Through early research in the 1940s and the 1950s the term was used by Joseph Wolpe's research group. The experimental tradition in clinical psychology

used it to refer to psycho-therapeutic techniques derived from

empirical research. It has since come to refer mainly to techniques for

increasing adaptive behaviour through reinforcement and decreasing

maladaptive behaviour through extinction or punishment (with emphasis on

the former). Two related terms are behaviour therapy and applied behaviour analysis.

Since techniques derived from behavioural psychology tend to be the

most effective in altering behaviour, most practitioners consider

behaviour modification along with behaviour therapy and applied

behaviour analysis to be founded in behaviourism.

While behaviour modification and applied behaviour analysis typically

uses interventions based on the same behavioural principles, many

behaviour modifiers who are not applied behaviour analysts tend to use

packages of interventions and do not conduct functional assessments

before intervening.

Possibly the first occurrence of the term "behavior therapy" was in a 1953 research project by B.F. Skinner, Ogden Lindsley, Nathan H. Azrin and Harry C. Solomon.

The paper talked about operant conditioning and how it could be used to

help improve the functioning of people who were diagnosed with chronic

schizophrenia. Early pioneers in behaviour therapy include Joseph Wolpe and Hans Eysenck.

In general, behaviour therapy is seen as having three distinct

points of origin: South Africa (Wolpe's group), The United States

(Skinner), and the United Kingdom (Rachman and Eysenck). Each had its

own distinct approach to viewing behaviour problems. Eysenck in

particular viewed behaviour problems as an interplay between personality

characteristics, environment, and behaviour. Skinner's group in the United States took more of an operant conditioning focus. The operant focus created a functional approach to assessment and interventions focused on contingency management such as the token economy and behavioural activation. Skinner's student Ogden Lindsley is credited with forming a movement called precision teaching,

which developed a particular type of graphing program called the

standard celeration chart to monitor the progress of clients. Skinner

became interested in the individualising of programs for improved

learning in those with or without disabilities and worked with Fred S. Keller to develop programmed instruction. Programmed instruction had some clinical success in aphasia rehabilitation. Gerald Patterson used programme instruction to develop his parenting text for children with conduct problems. With age, respondent conditioning appears to slow but operant conditioning remains relatively stable.

While the concept had its share of advocates and critics in the west,

its introduction in the Asian setting, particularly in India in the

early 1970s and its grand success were testament to the famous Indian psychologist H. Narayan Murthy's enduring commitment to the principles of behavioural therapy and biofeedback.

While many behaviour therapists remain staunchly committed to the basic operant and respondent paradigm, in the second half of the 20th century, many therapists coupled behaviour therapy with the cognitive therapy, of Aaron Beck, Albert Ellis, and [Donald Meichenbaum (psychologist)]]to form cognitive behaviour therapy.

In some areas the cognitive component had an additive effect (for

example, evidence suggests that cognitive interventions improve the

result of social phobia treatment.)

but in other areas it did not enhance the treatment, which led to the

pursuit of third generation behaviour therapies. Third generation

behaviour therapy uses basic principles of operant and respondent

psychology but couples them with functional analysis and a clinical formulation/case

conceptualisation of verbal behaviour more inline with view of the

behaviour analysts. Some research supports these therapies as being more

effective in some cases than cognitive therapy, but overall the question is still in need of answers.

Theoretical basis

The behavioural approach to therapy assumes that behaviour that

is associated with psychological problems develops through the same

processes of learning that affects the development of other behaviours.

Therefore, behaviourists see personality problems in the way that

personality was developed. They do not look at behaviour disorders as

something a person has but that it reflects how learning has influenced

certain people to behave in a certain way in certain situations.

Behaviour therapy is based upon the principles of classical conditioning developed by Ivan Pavlov and operant conditioning developed by B.F. Skinner.

Classical conditioning happens when a neutral stimulus comes right

before another stimulus that triggers a reflexive response. The idea is

that if the neutral stimulus and whatever other stimulus that triggers a

response is paired together often enough that the neutral stimulus will

produce the reflexive response. Operant conditioning has to do with rewards and punishments and how they can either strengthen or weaken certain behaviours.

Contingency management programs are a direct product of research from operant conditioning. These programs have been highly successful with those suffering from panic disorders, anxiety disorders, and phobias.

Systematic desensitisation and exposure and response prevention both evolved from respondent conditioning and have also received considerable research.

Behavior avoidance test (BAT) is a behavioural procedure in which

the therapist measures how long the client can tolerate an

anxiety-inducing stimulus.

The BAT falls under the exposure-based methods of behaviour therapy.

Exposure-based methods of behavioural therapy are well suited to the

treatment of phobias, which include intense and unreasonable fears

(e.g., of spiders, blood, public speaking).

The therapist needs some type of behavioural assessment to record the

continuing progress of a client undergoing an exposure-based treatment

for phobia. One simple assessment approach for this is the BAT. The BAT

approach is predicted on the assumption that the client's fear is the

main determinant of behaviour in the testing situation. BAT can be

conducted visual, virtually, or physically, depending on the clients'

maladaptive behaviour. Its application is not limited to phobias, it is

applied to various disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Current forms

Behavioral therapy based on operant and respondent principles has considerable evidence base to support its usage. This approach remains a vital area of clinical psychology and is often termed clinical behavior analysis. Behavioral psychotherapy has become increasingly contextual in recent years. Behavioral psychotherapy has developed greater interest in recent years in personality disorders as well as a greater focus on acceptance and complex case conceptualizations.

Functional analytic psychotherapy

One current form of behavioral psychotherapy is functional analytic psychotherapy. Functional analytic psychotherapy is a longer duration behavior therapy. Functional analytic therapy focuses on in-session use of reinforcement and is primarily a relationally-based therapy. As with most of the behavioral psychotherapies, functional analytic psychotherapy is contextual in its origins and nature. and draws heavily on radical behaviorism and functional contextualism.

Functional analytic psychotherapy holds to a process model of research, which makes it unique compared to traditional behavior therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Functional analytic psychotherapy has a strong research support.

Recent functional analytic psychotherapy research efforts are focusing

on management of aggressive inpatients.

Assessment

Behaviour

therapists complete a functional analysis or a functional assessment

that looks at four important areas: stimulus, organism, response and

consequences. The stimulus is the condition or environmental trigger that causes behaviour. An organism involves the internal responses of a person, like physiological responses, emotions and cognition.

A response is the behaviour that a person exhibits and the consequences

are the result of the behaviour. These four things are incorporated

into an assessment done by the behaviour therapist.

Most behaviour therapists use objective assessment methods like

structured interviews, objective psychological tests or different

behavioural rating forms. These types of assessments are used so that

the behaviour therapist can determine exactly what a client's problem

may be and establish a baseline for any maladaptive responses that the

client may have. By having this baseline, as therapy continues this same

measure can be used to check a client's progress, which can help

determine if the therapy is working. Behaviour therapists do not

typically ask the why questions but tend to be more focused on the how,

when, where and what questions. Tests such as the Rorschach inkblot test

or personality tests like the MMPI (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory)

are not commonly used for behavioural assessment because they are based

on personality trait theory assuming that a person's answer to these

methods can predict behaviour. Behaviour assessment is more focused on

the observations of a persons behaviour in their natural environment.

Behavioural assessment specifically attempts to find out what the

environmental and self-imposed variables are. These variables are the

things that are allowing a person to maintain their maladaptive

feelings, thoughts and behaviours. In a behavioural assessment "person

variables" are also considered. These "person variables" come from a

person's social learning history and they effect the way in which the

environment affects that person's behaviour. An example of a person

variable would be behavioural competence. Behavioural competence looks

at whether a person has the appropriate skills and behaviours that are

necessary when performing a specific response to a certain situation or

stimuli.

When making a behavioural assessment the behaviour therapist

wants to answer two questions: (1) what are the different factors

(environmental or psychological) that are maintaining the maladaptive

behaviour and (2) what type of behaviour therapy or technique that can

help the individual improve most effectively. The first question

involves looking at all aspects of a person, which can be summed up by

the acronym BASIC ID. This acronym stands for behaviour, affective

responses, sensory reactions, imagery, cognitive processes,

interpersonal relationships and drug use.

Clinical applications

Behaviour

therapy based its core interventions on functional analysis. Just a few

of the many problems that behaviour therapy have functionally analysed

include intimacy in couples relationships, forgiveness in couples, chronic pain, stress-related behaviour problems of being an adult child of an alcoholic, anorexia, chronic distress, substance abuse, depression, anxiety, insomnia, and obesity.

Functional analysis has even been applied to problems that

therapists commonly encounter like client resistance, partially engaged

clients and involuntary clients.

Applications to these problems have left clinicians with considerable

tools for enhancing therapeutic effectiveness. One way to enhance

therapeutic effectiveness is to use positive reinforcement or operant

conditioning. Although behaviour therapy is based on the general

learning model, it can be applied in a lot of different treatment

packages that can be specifically developed to deal with problematic

behaviours. Some of the more well known types of treatments are:

Relaxation training, systematic desensitization, virtual reality

exposure, exposure and response prevention techniques, social skills

training, modeling, behavioural rehearsal and homework, and aversion therapy and punishment.

Relaxation training involves clients learning to lower arousal to

reduce their stress by tensing and releasing certain muscle groups

throughout their body.

Systematic desensitization is a treatment in which the client slowly

substitutes a new learned response for a maladaptive response by moving

up a hierarchy of situations involving fear.

Systematic desensitization is based in part on counter conditioning.

Counter conditioning is learning new ways to change one response for

another and in the case of desensitization it is substituting that

maladaptive behaviour for a more relaxing behaviour. Exposure and response prevention techniques (also known as flooding and response prevention)

is the general technique in which a therapist exposes an individual to

anxiety-provoking stimuli while keeping them from having any avoidance

responses.

Virtual reality therapy provides realistic, computer-based

simulations of troublesome situations. The modeling process involves a

person being subjected to watching other individuals who demonstrate

behaviour that is considered adaptive and that should be adopted by the

client. This exposure involves not only the cues of the "model person"

as well as the situations of a certain behaviour that way the

relationship can be seen between the appropriateness of a certain

behaviour and situation in which that behaviour occurs is demonstrated.

With the behavioural rehearsal and homework treatment a client gets a

desired behaviour during a therapy session and then they practice and

record that behaviour between their sessions. Aversion therapy

and punishment is a technique in which an aversive (painful or

unpleasant) stimulus is used to decrease unwanted behaviours from

occurring. It is concerned with two procedures: 1) the procedures are

used to decrease the likelihood of the frequency of a certain behaviour

and 2) procedures that will reduce the attractiveness of certain

behaviours and the stimuli that elicit them.

The punishment side of aversion therapy is when an aversive stimulus is

presented at the same time that a negative stimulus and then they are

stopped at the same time when a positive stimulus or response is

presented. Examples of the type of negative stimulus or punishment that can be used is shock therapy treatments, aversive drug treatments as well as response cost contingent punishment which involves taking away a reward.

Applied behaviour analysis is using behavioural methods to modify

certain behaviours that are seen as being important socially or

personally. There are four main characteristics of applied behaviour

analysis. First behaviour analysis is focused mainly on overt behaviours

in an applied setting. Treatments are developed as a way to alter the

relationship between those overt behaviours and their consequences.

Another characteristic of applied behaviour analysis is how

it(behaviour analysis) goes about evaluating treatment effects. The

individual subject is where the focus of study is on, the investigation

is centered on the one individual being treated. A third characteristic

is that it focuses on what the environment does to cause significant

behaviour changes. Finally the last characteristic of applied behaviour

analysis is the use of those techniques that stem from operant and

classical conditioning such as providing reinforcement, punishment,

stimulus control and any other learning principles that may apply.

Social skills training teaches clients skills to access reinforcers and lessen life punishment. Operant conditioning procedures in meta-analysis had the largest effect size for training social skills, followed by modelling, coaching, and social cognitive techniques in that order. Social skills training has some empirical support particularly for schizophrenia. However, with schizophrenia, behavioural programs have generally lost favor.

Some other techniques that have been used in behaviour therapy

are contingency contracting, response costs, token economies,

biofeedback, and using shaping and grading task assignments.

Shaping and graded task assignments are used when behaviour that

needs to be learned is complex. The complex behaviours that need to be

learned are broken down into simpler steps where the person can achieve

small things gradually building up to the more complex behaviour. Each

step approximates the eventual goal and helps the person to expand their

activities in a gradual way. This behaviour is used when a person feels

that something in their lives can not be changed and life's tasks

appear to be overwhelming.

Another technique of behaviour therapy involves holding a client

or patient accountable of their behaviours in an effort to change them.

This is called a contingency contract, which is a formal written

contract between two or more people that defines the specific expected

behaviours that you wish to change and the rewards and punishments that

go along with that behaviour.

In order for a contingency contract to be official it needs to have

five elements. First it must state what each person will get if they

successfully complete the desired behaviour. Secondly those people

involved have to monitor the behaviours. Third, if the desired behaviour

is not being performed in the way that was agreed upon in the contract

the punishments that were defined in the contract must be done. Fourth

if the persons involved are complying with the contract they must

receive bonuses. The last element involves documenting the compliance

and noncompliance while using this treatment in order to give the

persons involved consistent feedback about the target behaviour and the

provision of reinforcers.

Token economies is a behaviour therapy technique where clients

are reinforced with tokens that are considered a type of currency that

can be used to purchase desired rewards, like being able to watch

television or getting a snack that they want when they perform

designated behaviours.

Token economies are mainly used in institutional and therapeutic

settings. In order for a token economy to be effective their must be

consistency in administering the program by the entire staff. Procedures

must be clearly defined so that there is no confusion among the

clients. Instead of looking for ways to punish the patients or to deny

them of rewards, the staff has to reinforce the positive behaviours so

that the clients will increase the occurrence of the desired behaviour.

Over time the tokens need to be replaced with less tangible rewards such

as compliments so that the client will be prepared when they leave the

institution and won't expect to get something every time they perform a

desired behaviour.

Closely related to token economies is a technique called response

costs. This technique can either be used with or without token

economies. Response costs is the punishment side of token economies

where there is a loss of a reward or privilege after someone performs an

undesirable behaviour. Like token economies this technique is used mainly in institutional and therapeutic settings.

Considerable policy implications have been inspired by

behavioural views of various forms of psychopathology. One form of

behaviour therapy, habit reversal training, has been found to be highly effective for treating tics.

In rehabilitation

Currently, there is a greater call for behavioral psychologists to be involved in rehabilitation efforts.

Treatment of mental disorders

Two large studies done by the Faculty of Health Sciences at Simon

Fraser University

indicates that both behaviour therapy and cognitive-behavioural therapy

(CBT) are equally effective for OCD. CBT has been shown to perform

slightly better at treating co-occurring depression.

Considerable policy implications have been inspired by

behavioural views of various forms of psychopathology. One form of

behaviour therapy (habit reversal training) has been found to be highly effective for treating tics.

There has been a development towards combining techniques to

treat psychiatric disorders. Cognitive interventions are used to enhance

the effects of more established behavioural interventions based on

operant and classical conditioning. An increased effort has also been

placed to address the interpersonal context of behaviour.

Behaviour therapy can be applied to a number of mental disorders

and in many cases is more effective for specific disorders as compared

to others. Behaviour therapy techniques can be used to deal with any

phobias that a person may have. Desensitization has also been applied to

other issues such as dealing with anger, if a person has trouble

sleeping and certain speech disorders.

Desensitization does not occur over night, there is a process of

treatment. Desensitization is done on a hierarchy and happens over a

number of sessions. The hierarchy goes from situations that make a person less anxious or nervous up to things that are considered to be extreme for the patient.

Modeling has been used in dealing with fears and phobias.

Modeling has been used in the treatment of fear of snakes as well as a

fear of water.

Aversive therapy techniques have been used to treat sexual deviations as well as alcoholism.

Exposure and prevention procedure techniques can be used to treat

people who have anxiety problems as well as any fears or phobias.

These procedures have also been used to help people dealing with any

anger issues as well as pathological grievers (people who have

distressing thoughts about a deceased person).

Virtual reality therapy deals with fear of heights, fear of flying, and a variety of other anxiety disorders.

VRT has also been applied to help people with substance abuse problems

reduce their responsiveness to certain cues that trigger their need to

use drugs.

Shaping and graded task assignments has been used in dealing with

suicide and depressed or inhibited individuals. This is used when a

patient feel hopeless and they have no way of changing their lives. This

hopelessness involves how the person reacts and responds to someone

else and certain situations and their perceived powerlessness to change

that situation that adds to the hopelessness. For a person with suicidal

ideation, it is important to start with small steps. Because that

person may perceive everything as being a big step, the smaller you

start the easier it will be for the person to master each step.

This technique has also been applied to people dealing with

agoraphobia, or fear of being in public places or doing something

embarrassing.

Contingency contracting has been used to deal with behaviour

problems in delinquents and when dealing with on task behaviours in

students.

Token economies are used in controlled environments and are found

mostly in psychiatric hospitals. They can be used to help patients with

different mental illnesses but it doesn't focus on the treatment of the

mental illness but instead on the behavioural aspects of a patient.

The response cost technique has been used to address a variety of

behaviours such as smoking, overeating, stuttering, and psychotic talk.

Treatment outcomes

Systematic desensitization has been shown to successfully treat

phobias about heights, driving, insects as well as any anxiety that a

person may have. Anxiety can include social anxiety, anxiety about

public speaking as well as test anxiety. It has been shown that the use

of systematic desensitization is an effective technique that can be

applied to a number of problems that a person may have.

When using modeling procedures this technique is often compared

to another behavioural therapy technique. When compared to

desensitization, the modeling technique does appear to be less

effective.

However it is clear that the greater the interaction between the

patient and the subject he is modeling the greater the effectiveness of

the treatment.

While undergoing exposure therapy a person usually needs five

sessions to see if the treatment is working. After five sessions

exposure treatment is seen to benefit the patient and help with their

problems. However even after five sessions it is recommended that the

patient or client should still continue treatment.

Virtual Reality treatment has shown to be effective for a fear of heights. It has also been shown to help with the treatment of a variety of anxiety disorders.

Virtual reality therapy can be very costly so therapists are still

awaiting results of controlled trials for VR treatment to see which

applications show the best results.

For those with suicidal ideation treatment depends on how severe

the person's depression and feeling of hopelessness is. If these things

are severe the person's response to completing small steps will not be

of importance to them because they don't consider it to be a big deal.

Generally those who aren't severely depressed or fearful, this

technique has been successful because the completion of simpler

activities build up their confidences and allows them to continue on to

more complex situations.

Contingency contracts have been seen to be effective in changing

any undesired behaviours of individuals. It has been seen to be

effective in treating behaviour problems in delinquents regardless of

the specific characteristics of the contract.

Token economies have been shown to be effective when treating

patients in psychiatric wards who had chronic schizophrenia. The results

showed that the contingent tokens were controlling the behaviour of the

patients.

Response costs has been shown to work in suppressing a variety of

behaviours such as smoking, overeating or stuttering with a diverse

group of clinical populations ranging from sociopaths to school

children. These behaviours that have been suppressed using this

technique often do not recover when the punishment contingency is

withdrawn. Also undesirable side effects that are usually seen with

punishment are not typically found when using the response cost

technique.

Third generation

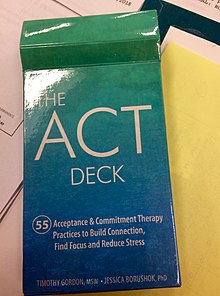

The third-generation behaviour therapy movement has been called clinical behavior analysis because it represents a movement away from cognitivism and back toward radical behaviourism and other forms of behaviourism, in particular functional analysis and behavioural models of verbal behaviour. This area includes acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP) (McCullough, 2000), behavioural activation (BA), functional analytic psychotherapy (FAP), integrative behavioural couples therapy and dialectical behavioural therapy. These approaches are squarely within the applied behaviour analysis tradition of behaviour therapy.

ACT may be the most well-researched of all the third-generation behaviour therapy models. It is based on relational frame theory.

Other authors object to the term "third generation" or "third wave" and

incorporate many of the "third wave" therapeutic techniques under the

general umbrella term of modern cognitive behavioral therapies.

Functional analytic psychotherapy is based on a functional analysis of the therapeutic relationship. It places a greater emphasis on the therapeutic context and returns to the use of in-session reinforcement. In general, 40 years of research supports the idea that in-session reinforcement of behaviour can lead to behavioural change.

Behavioural activation

emerged from a component analysis of cognitive behaviour therapy. This

research found no additive effect for the cognitive component. Behavioural activation is based on a matching model of reinforcement.

A recent review of the research, supports the notion that the use of

behavioural activation is clinically important for the treatment of

depression.

Integrative behavioural couples therapy

developed from dissatisfaction with traditional behavioural couples

therapy. Integrative behavioural couples therapy looks to Skinner (1966)

for the difference between contingency-shaped and rule-governed

behaviour.

It couples this analysis with a thorough functional assessment of the

couple's relationship. Recent efforts have used radical behavioural

concepts to interpret a number of clinical phenomena including

forgiveness.

Organizations

Many organisations exist for behaviour therapists around the world. The Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI) provides accreditation for training programs in behaviour therapy. The ABAI has a special interest group for practitioner issues, behavioral counseling, and clinical behavior analysis ABA:I. ABAI has larger special interest groups for autism and its peculiar and narrow interpretation of behavioral medicine. ABAI serves as the core intellectual home for behavior analysts. ABAI sponsors two conferences/year – one in the U.S. and one international.

In the United States, the American Psychological Association's Division 25 is the division for behaviour analysis.

The Association for Contextual Behavior Therapy is another professional

organisation. ACBS is home to many clinicians with specific interest in

third generation behaviour therapy. Doctoral-level behavior analysts

who are psychologists belong to American Psychological Association's division 25 – Behavior analysis. APA offers a diplomate in behavioral psychology.

The Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies

(formerly the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy) is

for those with a more cognitive orientation. The ABCT also has an

interest group in behavior analysis,

which focuses on clinical behavior analysis. In addition, the

Association for Behavioral an Cognitive Therapies has a special interest

group on addictions.

The World Association for Behavior Analysis offers a certification in behavior therapy.

Characteristics

By

nature, behavioural therapies are empirical (data-driven), contextual

(focused on the environment and context), functional (interested in the

effect or consequence a behaviour ultimately has), probabilistic

(viewing behaviour as statistically predictable), monistic (rejecting mind–body dualism and treating the person as a unit), and relational (analysing bidirectional interactions).

Behavioural therapy develops, adds and provides behavioural

intervention strategies and programs for clients, and training to people

who care to facilitate successful lives in the communities.

Training

Recent efforts in behavioral psychotherapy have focused on the supervision process. A key point of behavioral models of supervision is that the supervisory process parallels the behavioral psychotherapy.

Methods

- Behaviour management

- Behaviour modification

- Clinical behavior analysis

- Contingency management

- Covert conditioning

- Exposure and response prevention

- Flooding

- Habit reversal training

- Matching law

- Modeling

- Observational learning

- Operant conditioning

- Professional practice of behavior analysis

- Respondent conditioning

- Systematic desensitisation