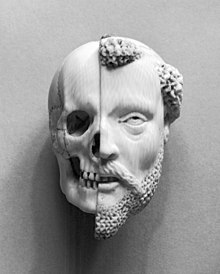

The human skull is used universally as a symbol of death.

Statue of Death, personified as a human skeleton dressed in a shroud and clutching a scythe, from the Cathedral of Trier in Trier, Germany

Death tending to his flowers, in Kuoleman Puutarha, Hugo Simberg (1906)

Death is the permanent cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Phenomena which commonly bring about death include aging, predation, malnutrition, disease, suicide, homicide, starvation, dehydration, and accidents or major trauma resulting in terminal injury. In most cases, bodies of living organisms begin to decompose shortly after death.

Death – particularly the death of humans – has commonly been considered a sad or unpleasant occasion, due to the affection for the being that has died and the termination of social and familial bonds with the deceased. Other concerns include fear of death, necrophobia, anxiety, sorrow, grief, emotional pain, depression, sympathy, compassion, solitude, or saudade. Many cultures and religions have the idea of an afterlife, and also hold the idea of reward or judgement and punishment for past sin.

Senescence

A dead Eurasian magpie

Senescence

refers to a scenario when a living being is able to survive all

calamities, but eventually dies due to causes relating to old age.

Animal and plant cells normally reproduce and function during the whole

period of natural existence, but the aging process derives from

deterioration of cellular activity and ruination of regular functioning.

Aptitude of cells for gradual deterioration and mortality means that

cells are naturally sentenced to stable and long-term loss of living

capacities, even despite continuing metabolic reactions and viability.

In the United Kingdom, for example, nine out of ten of all the deaths

that occur on a daily basis relates to senescence, while around the

world it accounts for two-thirds of 150,000 deaths that take place daily

(Hayflick & Moody, 2003).

Almost all animals who survive external hazards to their biological functioning eventually die from biological aging, known in life sciences as "senescence". Some organisms experience negligible senescence, even exhibiting biological immortality. These include the jellyfish Turritopsis dohrnii, the hydra, and the planarian. Unnatural causes of death include suicide and predation. From all causes, roughly 150,000 people die around the world each day.

Of these, two thirds die directly or indirectly due to senescence, but

in industrialized countries – such as the United States, the United

Kingdom, and Germany – the rate approaches 90% (i.e., nearly nine out of

ten of all deaths are related to senescence).

Physiological death is now seen as a process, more than an event: conditions once considered indicative of death are now reversible. Where in the process a dividing line is drawn between life and death depends on factors beyond the presence or absence of vital signs. In general, clinical death is neither necessary nor sufficient for a determination of legal death. A patient with working heart and lungs determined to be brain dead can be pronounced legally dead without clinical death occurring. As scientific knowledge and medicine advance, formulating a precise medical definition of death becomes more difficult.

Diagnosis

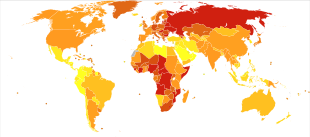

World Health Organization estimated number of deaths per million persons in 2012

1,054–4,598

4,599–5,516

5,517–6,289

6,290–6,835

6,836–7,916

7,917–8,728

8,729–9,404

9,405–10,433

10,434–12,233

12,234–17,141

Signs

Signs of death or strong indications that a warm-blooded animal is no longer alive are:

- Respiratory arrest (no breathing)

- Cardiac arrest (no pulse)

- Brain death (no neuronal activity)

- Pallor mortis, paleness which happens in the 15–120 minutes after death

- Algor mortis, the reduction in body temperature following death. This is generally a steady decline until matching ambient temperature

- Rigor mortis, the limbs of the corpse become stiff (Latin rigor) and difficult to move or manipulate

- Livor mortis, a settling of the blood in the lower (dependent) portion of the body

- Putrefaction, the beginning signs of decomposition

- Decomposition, the reduction into simpler forms of matter, accompanied by a strong, unpleasant odor.

- Skeletonization, the end of decomposition, where all soft tissues have decomposed, leaving only the skeleton.

- Fossilization, the natural preservation of the skeletal remains formed over a very long period

Problems of definition

A flower, a skull and an hourglass stand for life, death and time in this 17th-century painting by Philippe de Champaigne

French – 16th-/17th-century ivory pendant, Monk and Death, recalling mortality and the certainty of death (Walters Art Museum)

The concept of death is a key to human understanding of the phenomenon.

There are many scientific approaches and various interpretations of the

concept. Additionally, the advent of life-sustaining therapy and the

numerous criteria for defining death from both a medical and legal

standpoint, have made it difficult to create a single unifying

definition.

One of the challenges in defining death is in distinguishing it from life.

As a point in time, death would seem to refer to the moment at which

life ends. Determining when death has occurred is difficult, as

cessation of life functions is often not simultaneous across organ

systems.

Such determination therefore requires drawing precise conceptual

boundaries between life and death. This is difficult, due to there being

little consensus on how to define life.

It is possible to define life in terms of consciousness. When

consciousness ceases, a living organism can be said to have died. One of

the flaws in this approach is that there are many organisms which are

alive but probably not conscious (for example, single-celled organisms).

Another problem is in defining consciousness, which has many different

definitions given by modern scientists, psychologists and philosophers.

Additionally, many religious traditions, including Abrahamic and Dharmic

traditions, hold that death does not (or may not) entail the end of

consciousness. In certain cultures, death is more of a process than a

single event. It implies a slow shift from one spiritual state to

another.

Other definitions for death focus on the character of cessation of something. More specifically, death occurs when a living entity experiences irreversible cessation of all functioning. As it pertains to human life, death is an irreversible process where someone loses their existence as a person.

Historically, attempts to define the exact moment of a human's

death have been subjective, or imprecise. Death was once defined as the

cessation of heartbeat (cardiac arrest) and of breathing, but the development of CPR and prompt defibrillation

have rendered that definition inadequate because breathing and

heartbeat can sometimes be restarted. This type of death where

circulatory and respiratory arrest happens is known as the circulatory

definition of death (DCDD). Proponents of the DCDD believe that this

definition is reasonable because a person with permanent loss of

circulatory and respiratory function should be considered dead.

Critics of this definition state that while cessation of these

functions may be permanent, it does not mean the situation is not

irreversible, because if CPR was applied, the person could be revived.

Thus, the arguments for and against the DCDD boil down to a matter of

defining the actual words "permanent" and "irreversible," which further

complicates the challenge of defining death. Furthermore, events which

were causally

linked to death in the past no longer kill in all circumstances;

without a functioning heart or lungs, life can sometimes be sustained

with a combination of life support devices, organ transplants and artificial pacemakers.

Today, where a definition of the moment of death is required,

doctors and coroners usually turn to "brain death" or "biological death"

to define a person as being dead; people are considered dead when the

electrical activity in their brain ceases. It is presumed that an end of

electrical activity indicates the end of consciousness. Suspension of consciousness must be permanent, and not transient, as occurs during certain sleep stages, and especially a coma. In the case of sleep, EEGs can easily tell the difference.

The category of "brain death" is seen as problematic by some

scholars. For instance, Dr. Franklin Miller, senior faculty member at

the Department of Bioethics, National Institutes of Health, notes: "By

the late 1990s... the equation of brain death with death of the human

being was increasingly challenged by scholars, based on evidence

regarding the array of biological functioning displayed by patients

correctly diagnosed as having this condition who were maintained on

mechanical ventilation for substantial periods of time. These patients

maintained the ability to sustain circulation and respiration, control

temperature, excrete wastes, heal wounds, fight infections and, most

dramatically, to gestate fetuses (in the case of pregnant "brain-dead"

women)."

While "brain death" is viewed as problematic by some scholars,

there are certainly proponents of it that believe this definition of

death is the most reasonable for distinguishing life from death. The

reasoning behind the support for this definition is that brain death has

a set of criteria that is reliable and reproducible.

Also, the brain is crucial in determining our identity or who we are as

human beings. The distinction should be made that "brain death" cannot

be equated with one who is in a vegetative state or coma, in that the

former situation describes a state that is beyond recovery.

Those people maintaining that only the neo-cortex

of the brain is necessary for consciousness sometimes argue that only

electrical activity should be considered when defining death. Eventually

it is possible that the criterion for death will be the permanent and

irreversible loss of cognitive function, as evidenced by the death of the cerebral cortex. All hope of recovering human thought and personality

is then gone given current and foreseeable medical technology. At

present, in most places the more conservative definition of death –

irreversible cessation of electrical activity in the whole brain, as

opposed to just in the neo-cortex – has been adopted (for example the Uniform Determination Of Death Act in the United States). In 2005, the Terri Schiavo case brought the question of brain death and artificial sustenance to the front of American politics.

Even by whole-brain criteria, the determination of brain death

can be complicated. EEGs can detect spurious electrical impulses, while

certain drugs, hypoglycemia, hypoxia, or hypothermia

can suppress or even stop brain activity on a temporary basis. Because

of this, hospitals have protocols for determining brain death involving

EEGs at widely separated intervals under defined conditions.

In the past, adoption of this whole-brain definition was a

conclusion of the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical

Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research in 1980.

They concluded that this approach to defining death sufficed in

reaching a uniform definition nationwide. A multitude of reasons were

presented to support this definition including: uniformity of standards

in law for establishing death; consumption of a family's fiscal

resources for artificial life support; and legal establishment for

equating brain death with death in order to proceed with organ donation.

Aside from the issue of support of or dispute against brain

death, there is another inherent problem in this categorical definition:

the variability of its application in medical practice. In 1995, the

American Academy of Neurology (AAN), established a set of criteria that

became the medical standard for diagnosing neurologic death. At that

time, three clinical features had to be satisfied in order to determine

“irreversible cessation” of the total brain including: coma with clear

etiology, cessation of breathing, and lack of brainstem reflexes.

This set of criteria was then updated again most recently in 2010, but

substantial discrepancies still remain across hospitals and medical

specialties.

The problem of defining death is especially imperative as it pertains to the Dead donor rule,

which could be understood as one of the following interpretations of

the rule: there must be an official declaration of death in a person

before starting organ procurement or that organ procurement cannot

result in death of the donor.

A great deal of controversy has surrounded the definition of death and

the dead donor rule. Advocates of the rule believe the rule is

legitimate in protecting organ donors while also countering against any

moral or legal objection to organ procurement. Critics, on the other

hand, believe that the rule does not uphold the best interests of the

donors and that the rule does not effectively promote organ donation.

Legal

The death of a person has legal consequences that may vary between different jurisdictions.

A death certificate

is issued in most jurisdictions, either by a doctor, or by an

administrative office upon presentation of a doctor's declaration of

death.

Misdiagnosed

Antoine Wiertz's painting of a man buried alive

There are many anecdotal references to people being declared dead by

physicians and then "coming back to life", sometimes days later in their

own coffin, or when embalming

procedures are about to begin. From the mid-18th century onwards, there

was an upsurge in the public's fear of being mistakenly buried alive, and much debate about the uncertainty of the signs of death. Various suggestions were made to test for signs of life before burial, ranging from pouring vinegar and pepper into the corpse's mouth to applying red hot pokers to the feet or into the rectum. Writing in 1895, the physician J.C. Ouseley claimed that as many as 2,700 people were buried prematurely each year in England and Wales, although others estimated the figure to be closer to 800.

In cases of electric shock, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for an hour or longer can allow stunned nerves

to recover, allowing an apparently dead person to survive. People found

unconscious under icy water may survive if their faces are kept

continuously cold until they arrive at an emergency room. In science fiction scenarios where such technology is readily available, real death is distinguished from reversible death.

Causes

The leading cause of human death in developing countries is infectious disease. The leading causes in developed countries are atherosclerosis (heart disease and stroke), cancer, and other diseases related to obesity and aging. By an extremely wide margin, the largest unifying cause of death in the developed world is biological aging, leading to various complications known as aging-associated diseases. These conditions cause loss of homeostasis, leading to cardiac arrest, causing loss of oxygen and nutrient supply, causing irreversible deterioration of the brain and other tissues. Of the roughly 150,000 people who die each day across the globe, about two thirds die of age-related causes. In industrialized nations, the proportion is much higher, approaching 90%. With improved medical capability, dying has become a condition to be managed. Home deaths, once commonplace, are now rare in the developed world.

American children smoking in 1910. Tobacco smoking caused an estimated 100 million deaths in the 20th century.

In developing nations, inferior sanitary conditions and lack of access to modern medical technology makes death from infectious diseases more common than in developed countries. One such disease is tuberculosis, a bacterial disease which killed 1.8M people in 2015. Malaria causes about 400–900M cases of fever and 1–3M deaths annually. AIDS death toll in Africa may reach 90–100M by 2025.

According to Jean Ziegler (United Nations Special Reporter on the Right to Food, 2000 – Mar 2008), mortality due to malnutrition

accounted for 58% of the total mortality rate in 2006. Ziegler says

worldwide approximately 62M people died from all causes and of those

deaths more than 36M died of hunger or diseases due to deficiencies in micronutrients.

Tobacco

smoking killed 100 million people worldwide in the 20th century and

could kill 1 billion people around the world in the 21st century, a World Health Organization report warned.

Many leading developed world causes of death can be postponed by diet and physical activity, but the accelerating incidence of disease with age still imposes limits on human longevity. The evolutionary cause of aging

is, at best, only just beginning to be understood. It has been

suggested that direct intervention in the aging process may now be the

most effective intervention against major causes of death.

Selye proposed a unified non-specific approach to many causes of death. He demonstrated that stress decreases adaptability of an organism and proposed to describe the adaptability as a special resource, adaptation energy. The animal dies when this resource is exhausted.

Selye assumed that the adaptability is a finite supply, presented at

birth. Later on, Goldstone proposed the concept of a production or

income of adaptation energy which may be stored (up to a limit), as a

capital reserve of adaptation.

In recent works, adaptation energy is considered as an internal

coordinate on the "dominant path" in the model of adaptation. It is

demonstrated that oscillations of well-being appear when the reserve of

adaptability is almost exhausted.

In 2012, suicide overtook car crashes for leading causes of human injury deaths in the U.S., followed by poisoning, falls and murder.

Causes of death are different in different parts of the world. In

high-income and middle income countries nearly half up to more than two

thirds of all people live beyond the age of 70 and predominantly die of

chronic diseases. In low-income countries, where less than one in five

of all people reach the age of 70, and more than a third of all deaths

are among children under 15, people predominantly die of infectious

diseases.

Autopsy

An autopsy is portrayed in The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, by Rembrandt

An autopsy, also known as a postmortem examination or an obduction, is a medical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a human corpse to determine the cause and manner of a person's death and to evaluate any disease or injury that may be present. It is usually performed by a specialized medical doctor called a pathologist.

Autopsies are either performed for legal or medical purposes. A

forensic autopsy is carried out when the cause of death may be a

criminal matter, while a clinical or academic autopsy is performed to

find the medical cause of death and is used in cases of unknown or

uncertain death, or for research purposes. Autopsies can be further

classified into cases where external examination suffices, and those

where the body is dissected and an internal examination is conducted.

Permission from next of kin

may be required for internal autopsy in some cases. Once an internal

autopsy is complete the body is generally reconstituted by sewing it

back together. Autopsy is important in a medical environment and may

shed light on mistakes and help improve practices.

A necropsy, which is not always a medical procedure, was a term

previously used to describe an unregulated postmortem examination . In

modern times, this term is more commonly associated with the corpses of

animals.

Cryonics

Technicians prepare a body for cryopreservation in 1985.

Cryonics (from Greek κρύος 'kryos-' meaning 'icy cold') is the low-temperature preservation of animals and humans who cannot be sustained by contemporary medicine, with the hope that healing and resuscitation may be possible in the future.

Cryopreservation

of people or large animals is not reversible with current technology.

The stated rationale for cryonics is that people who are considered dead

by current legal or medical definitions may not necessarily be dead

according to the more stringent information-theoretic definition of

death.

Some scientific literature is claimed to support the feasibility of cryonics. Medical science and cryobiologists generally regards cryonics with skepticism.

Life extension

Life extension refers to an increase in maximum or average lifespan, especially in humans, by slowing down or reversing the processes of aging. Average lifespan is determined by vulnerability to accidents and age or lifestyle-related afflictions such as cancer, or cardiovascular disease. Extension of average lifespan can be achieved by good diet, exercise and avoidance of hazards such as smoking. Maximum lifespan is also determined by the rate of aging for a species inherent in its genes. Currently, the only widely recognized method of extending maximum lifespan is calorie restriction. Theoretically, extension of maximum lifespan can be achieved by reducing the rate of aging damage, by periodic replacement of damaged tissues, or by molecular repair or rejuvenation of deteriorated cells and tissues.

A United States poll found that religious people and irreligious

people, as well as men and women and people of different economic

classes have similar rates of support for life extension, while Africans

and Hispanics have higher rates of support than white people. 38 percent of the polled said they would desire to have their aging process cured.

Researchers of life extension are a subclass of biogerontologists known as "biomedical gerontologists".

They try to understand the nature of aging and they develop treatments

to reverse aging processes or to at least slow them down, for the

improvement of health and the maintenance of youthful vigor at every

stage of life. Those who take advantage of life extension findings and

seek to apply them upon themselves are called "life extensionists" or

"longevists". The primary life extension strategy currently is to apply

available anti-aging methods in the hope of living long enough to

benefit from a complete cure to aging once it is developed.

Reperfusion

"One of medicine's new frontiers: treating the dead", recognizes that

cells that have been without oxygen for more than five minutes die, not from lack of oxygen, but rather when their oxygen supply is resumed. Therefore, practitioners of this approach, e.g., at the Resuscitation Science institute at the University of Pennsylvania, "aim to reduce oxygen uptake, slow metabolism and adjust the blood chemistry for gradual and safe reperfusion."

Location

Before about 1930, most people in Western countries died in their own

homes, surrounded by family, and comforted by clergy, neighbors, and

doctors making house calls. By the mid-20th century, half of all Americans died in a hospital. By the start of the 21st century, only about 20-25% of people in developed countries died outside of a medical institution. The shift away from dying at home, towards dying in a professional medical environment, has been termed the "Invisible Death". This shift occurred gradually over the years, until most deaths now occur outside the home.

Emotional response

Many people are afraid of dying. Talking about it, thinking about

it, or planning for their own deaths causes them discomfort. This fear

may cause them to put off financial planning, preparing a will and testament, or requesting help from a hospice organization.

Different people have different responses to the idea of their own deaths.

Philosopher Galen Strawson writes that the death that many people wish for is an instant, painless, unexperienced annihilation.

In this unlikely scenario, the person dies without realizing it and

without being able fear it. One moment the person is walking, eating,

or sleeping, and the next moment, the person is dead. Strawson reasons

that this type of death would not take anything away from the person, as

he believes that a person cannot have a legitimate claim to ownership

in the future.

Society and culture

The regent duke Charles (later king Charles IX of Sweden) insulting the corpse of Klaus Fleming. Albert Edelfelt, 1878.

Dead bodies can be mummified either naturally, as this one from Guanajuato, or by intention, as those in ancient Egypt.

In society, the nature of death and humanity's awareness of its own mortality has for millennia been a concern of the world's religious traditions and of philosophical inquiry. This includes belief in resurrection or an afterlife (associated with Abrahamic religions), reincarnation or rebirth (associated with Dharmic religions), or that consciousness permanently ceases to exist, known as eternal oblivion (associated with atheism).

Commemoration ceremonies after death may include various mourning, funeral practices and ceremonies of honouring the deceased. The physical remains of a person, commonly known as a corpse or body, are usually interred whole or cremated, though among the world's cultures there are a variety of other methods of mortuary disposal. In the English language, blessings directed towards a dead person include rest in peace, or its initialism RIP.

Death is the center of many traditions and organizations; customs

relating to death are a feature of every culture around the world. Much

of this revolves around the care of the dead, as well as the afterlife and the disposal of bodies upon the onset of death. The disposal of human corpses does, in general, begin with the last offices before significant time has passed, and ritualistic ceremonies often occur, most commonly interment or cremation. This is not a unified practice; in Tibet, for instance, the body is given a sky burial

and left on a mountain top. Proper preparation for death and techniques

and ceremonies for producing the ability to transfer one's spiritual

attainments into another body (reincarnation) are subjects of detailed study in Tibet. Mummification or embalming is also prevalent in some cultures, to retard the rate of decay.

Legal aspects of death are also part of many cultures, particularly the settlement of the deceased estate and the issues of inheritance and in some countries, inheritance taxation.

Gravestones in Kyoto, Japan

Capital punishment

is also a culturally divisive aspect of death. In most jurisdictions

where capital punishment is carried out today, the death penalty is

reserved for premeditated murder, espionage, treason, or as part of military justice. In some countries, sexual crimes, such as adultery and sodomy, carry the death penalty, as do religious crimes such as apostasy, the formal renunciation of one's religion. In many retentionist countries, drug trafficking is also a capital offense. In China, human trafficking and serious cases of corruption are also punished by the death penalty. In militaries around the world courts-martial have imposed death sentences for offenses such as cowardice, desertion, insubordination, and mutiny.

Death in warfare and in suicide attack also have cultural links, and the ideas of dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, mutiny punishable by death, grieving relatives of dead soldiers and death notification are embedded in many cultures. Recently in the western world, with the increase in terrorism following the September 11 attacks, but also further back in time with suicide bombings, kamikaze missions in World War II and suicide missions in a host of other conflicts in history, death for a cause by way of suicide attack, and martyrdom have had significant cultural impacts.

Suicide is also present in some subcultures. In recent times for

example in the emo subculture. The qualitative research has shown emo

respondents reported “attitudes including high acceptance for suicidal

behavior and self-injury”. And concluded: “The identification with the

emo youth subculture is considered to be a factor strengthening

vulnerability towards risky behaviors.”

Suicide in general, and particularly euthanasia, are also points of cultural debate. Both acts are understood very differently in different cultures. In Japan, for example, ending a life with honor by seppuku was considered a desirable death, whereas according to traditional Christian and Islamic cultures, suicide is viewed as a sin. Death is personified in many cultures, with such symbolic representations as the Grim Reaper, Azrael, the Hindu God Yama and Father Time.

In Brazil,

a human death is counted officially when it is registered by existing

family members at a cartório, a government-authorized registry. Before

being able to file for an official death, the deceased must have been

registered for an official birth at the cartório. Though a Public

Registry Law guarantees all Brazilian citizens the right to register

deaths, regardless of their financial means, of their family members

(often children), the Brazilian government has not taken away the

burden, the hidden costs and fees, of filing for a death. For many

impoverished families, the indirect costs and burden of filing for a

death lead to a more appealing, unofficial, local, cultural burial,

which in turn raises the debate about inaccurate mortality rates.

Talking about death and witnessing it is a difficult issue with

most cultures. Western societies may like to treat the dead with the

utmost material respect, with an official embalmer and associated rites.

Eastern societies (like India) may be more open to accepting it as a fait accompli, with a funeral procession of the dead body ending in an open air burning-to-ashes of the same.

Consciousness

Much interest and debate surround the question of what happens to

one's consciousness as one's body dies. The belief in the permanent loss

of consciousness after death is often called eternal oblivion. Belief that the stream of consciousness is preserved after physical death is described by the term afterlife. Neither are likely to ever be confirmed without the ponderer having to actually die.

In biology

Earthworms are a good example of soil-dwelling detritivores.

After death, the remains of an organism become part of the biogeochemical cycle, during which animals may be consumed by a predator or a scavenger. Organic material may then be further decomposed by detritivores, organisms which recycle detritus, returning it to the environment for reuse in the food chain,

where these chemicals may eventually end up being consumed and

assimilated into the cells of a living organism. Examples of

detritivores include earthworms, woodlice and dung beetles.

Microorganisms

also play a vital role, raising the temperature of the decomposing

matter as they break it down into yet simpler molecules. Not all

materials need to be fully decomposed. Coal, a fossil fuel formed over vast tracts of time in swamp ecosystems, is one example.

Natural selection

Contemporary evolutionary theory sees death as an important part of the process of natural selection. It is considered that organisms less adapted to their environment are more likely to die having produced fewer offspring, thereby reducing their contribution to the gene pool. Their genes are thus eventually bred out of a population, leading at worst to extinction and, more positively, making the process possible, referred to as speciation. Frequency of reproduction

plays an equally important role in determining species survival: an

organism that dies young but leaves numerous offspring displays,

according to Darwinian criteria, much greater fitness than a long-lived organism leaving only one.

Extinction

Extinction is the cessation of existence of a species or group of taxa, reducing biodiversity. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of that species (although the capacity to breed and recover may have been lost before this point). Because a species' potential range

may be very large, determining this moment is difficult, and is usually

done retrospectively. This difficulty leads to phenomena such as Lazarus taxa, where species presumed extinct abruptly "reappear" (typically in the fossil record) after a period of apparent absence. New species arise through the process of speciation, an aspect of evolution. New varieties of organisms arise and thrive when they are able to find and exploit an ecological niche – and species become extinct when they are no longer able to survive in changing conditions or against superior competition.

Evolution of aging and mortality

Inquiry into the evolution of aging aims to explain why so many

living things and the vast majority of animals weaken and die with age

(exceptions include Hydra and the already cited jellyfish Turritopsis dohrnii, which research shows to be biologically immortal). The evolutionary origin of senescence remains one of the fundamental puzzles of biology. Gerontology specializes in the science of human aging processes.

Organisms showing only asexual reproduction (e.g. bacteria, some protists, like the euglenoids and many amoebozoans) and unicellular organisms with sexual reproduction (colonial or not, like the volvocine algae Pandorina and Chlamydomonas) are "immortal" at some extent, dying only due to external hazards, like being eaten or meeting with a fatal accident. In multicellular organisms (and also in multinucleate ciliates), with a Weismannist development, that is, with a division of labor between mortal somatic (body) cells and "immortal" germ (reproductive) cells, death becomes an essential part of life, at least for the somatic line.

The Volvox

algae are among the simplest organisms to exhibit that division of

labor between two completely different cell types, and as a consequence

include death of somatic line as a regular, genetically regulated part

of its life history.

Religious views

Death is an important subject of religious doctrine.

Buddhism

In Buddhist doctrine and practice, death plays an important role. Awareness of death was what motivated Prince Siddhartha to strive to find the "deathless" and finally to attain enlightenment. In Buddhist doctrine, death functions as a reminder of the value of having been born as a human being.

Being reborn as a human being is considered the only state in which one

can attain enlightenment. Therefore, death helps remind oneself that

one should not take life for granted. The belief in rebirth among

Buddhists does not necessarily remove death anxiety, since all existence in the cycle of rebirth is considered filled with suffering, and being reborn many times does not necessarily mean that one progresses.

Death is part of several key Buddhist tenets, such as the Four Noble Truths and dependent origination.

Christianity

Islam

Judaism

A yahrtzeit candle lit in memory of a loved one on the anniversary of the death

Death is seen in Judaism as tragic and intimidating. Persons who come into contact with corpses are ritually impure. There are a variety of beliefs about the afterlife

within Judaism, but none of them contradict the preference of life over

death. This is partially because death puts a cessation to the

possibility of fulfilling any commandments.

Language around death

Study of Skeletons, c. 1510, by Leonardo da Vinci

The word death comes from Old English dēaþ, which in turn comes from Proto-Germanic *dauþuz (reconstructed by etymological analysis). This comes from the Proto-Indo-European stem *dheu- meaning the "process, act, condition of dying".

The concept and symptoms of death, and varying degrees of

delicacy used in discussion in public forums, have generated numerous

scientific, legal, and socially acceptable terms or euphemisms for

death. When a person has died, it is also said they have passed away, passed on, expired, or are gone, among numerous other socially accepted, religiously specific, slang, and irreverent terms.

As a formal reference to a dead person, it has become common practice to use the participle form of "decease", as in the deceased; another noun form is decedent.

Bereft of life, the dead person is then a corpse, cadaver, a body, a set of remains, and when all flesh has rotted away, a skeleton. The terms carrion and carcass can also be used, though these more often connote the remains of non-human animals. The ashes left after a cremation are sometimes referred to by the neologism cremains, a portmanteau of "cremation" and "remains".