Sign reads "Political change not climate change" at the Melbourne climate strike in 2019

The complex politics of global warming results from numerous cofactors arising from the global economy's dependence on carbon dioxide (CO

2) emitting fossil fuels; and because greenhouse gases such as CO

2, methane and N

2O (mostly from agriculture) cause global warming — making global warming a non-traditional environmental challenge.

2) emitting fossil fuels; and because greenhouse gases such as CO

2, methane and N

2O (mostly from agriculture) cause global warming — making global warming a non-traditional environmental challenge.

Overview

- Implications to all aspects of a nation-state's economy: The vast majority of the world economy relies on energy sources or manufacturing techniques that release greenhouse gases at almost every stage of production, transportation, storage, delivery & disposal while a consensus of the world's scientists attribute global warming to the release of CO

2 and other greenhouse gases. This intimate linkage between global warming and economic vitality implicates almost every aspect of a nation-state's economy; - Perceived lack of adequate advanced energy technologies: Fossil fuel abundance and low prices continue to put pressure on the development of adequate advanced energy technologies that can realistically replace the role of fossil fuels—as of 2010, over 91% of the world's energy is derived from fossil fuels and non-carbon-neutral technologies. Without adequate and cost effective post-hydrocarbon energy sources, it is unlikely the countries of the developed or developing world would accept policies that would materially affect their economic vitality or economic development prospects;

- Industrialization of the developing world: As developing nations industrialize their energy needs increase and since conventional energy sources produce CO

2, the CO

2 emissions of developing countries are beginning to rise at a time when the scientific community, global governance institutions and advocacy groups are telling the world that CO

2 emissions should be decreasing. Without access to cost effective and abundant energy sources many developing countries see climate change as a hindrance to their unfettered economic development; - Metric selection (transparency) and perceived responsibility / ability to respond:

Among the countries of the world, disagreements exist over which

greenhouse gas emission metrics should be used like total emissions per

year, per capita emissions per year, CO2 emissions only, deforestation emissions, livestock emissions or even total historical emissions. Historically, the release of CO

2 has not been even among all nation-states, and nation-states have challenges with determining who should restrict emissions and at what point of their industrial development they should be subject to such commitments; - Vulnerable developing countries and developed country legacy emissions:

Some developing nations blame the developed world for having created

the global warming crisis because it was the developed countries that

emitted most of the CO

2 over the twentieth century and vulnerable countries perceive that it should be the developed countries that should pay to fix the problem; - Consensus-driven global governance models: The global governance institutions that evolved during the 20th century are all consensus driven deliberative forums where agreement is difficult to achieve and even when agreement is achieved it is almost impossible to enforce;

- Well organized and funded special-interest lobbying bodies: Special interest lobbying by well organized groups distort and amplify aspects of the challenge (fossil fuels lobby, other special interest lobbying);

- Politicization of climate science: Although there is a consensus on the science of global warming and its likely effects—some special interests groups work to suppress the consensus while others work to amplify the alarm of global warming. All parties that engage in such acts add to the politicization of the science of global warming. The result is a clouding of the reality of the global warming problem.

The focus areas for global warming politics are Adaptation, Mitigation, Finance, Technology and Losses

which are well quantified and studied but the urgency of the global

warming challenge combined with the implication to almost every facet of

a nation-state's economic interests places significant burdens on the

established largely-voluntary global institutions that have developed

over the last century; institutions that have been unable to effectively

reshape themselves and move fast enough to deal with this unique

challenge. Rapidly developing countries which see traditional energy

sources as a means to fuel their development, well funded environmental

lobbying groups and an established fossil fuel energy paradigm boasting a

mature and sophisticated political lobbying infrastructure all combine

to make global warming politics extremely polarized. Distrust between

developed and developing countries at most international conferences

that seek to address the topic add to the challenges. Further adding to

the complexity is the advent of the Internet and the development of

media technologies like blogs and other mechanisms for disseminating

information that enable the exponential growth in production and

dissemination of competing points of view which make it nearly

impossible for the development and dissemination of an objective view

into the enormity of the subject matter and its politics.

Nontraditional environmental challenge

Traditional environmental challenges generally involve behavior by a

small group of industries which create products or services for a

limited set of consumers in a manner that causes some form of damage to

the environment which is clear. As an example, a gold mine might

release a dangerous chemical byproduct into a waterway that kills the

fish there: a clear environmental damage. By contrast, CO

2 is a naturally occurring colorless odorless trace gas that is essential to the biosphere. Carbon dioxide (CO

2) is produced by all animals and utilized by plants and algae to build their body structures. Plant structures buried for tens of millions of years sequester carbon to form coal, oil and gas which modern industrial societies find essential to economic vitality. Over 80% of the worlds energy is derived from CO

2 emitting fossil fuels and over 91% of the world's energy is derived from non carbon-neutral energy sources. Scientists attribute the increases of CO

2 in the atmosphere to industrial emissions and scientists agree the increase in CO

2 causes global warming. This essential nature to the world's economies combined with the complexity of the science and the interests of countless interested parties make climate change a non-traditional environmental challenge.

2 is a naturally occurring colorless odorless trace gas that is essential to the biosphere. Carbon dioxide (CO

2) is produced by all animals and utilized by plants and algae to build their body structures. Plant structures buried for tens of millions of years sequester carbon to form coal, oil and gas which modern industrial societies find essential to economic vitality. Over 80% of the worlds energy is derived from CO

2 emitting fossil fuels and over 91% of the world's energy is derived from non carbon-neutral energy sources. Scientists attribute the increases of CO

2 in the atmosphere to industrial emissions and scientists agree the increase in CO

2 causes global warming. This essential nature to the world's economies combined with the complexity of the science and the interests of countless interested parties make climate change a non-traditional environmental challenge.

Carbon dioxide and a nation-state's economy

The vast majority of developed countries rely on CO

2 emitting energy sources for large components of their economic activity. Fossil fuel energy generally dominates the following areas of an OECD economy:

2 emitting energy sources for large components of their economic activity. Fossil fuel energy generally dominates the following areas of an OECD economy:

- agriculture (fertilizers, irrigation, plowing, planting, harvesting, pesticides)

- transportation & distribution (automobiles, shipping, trains, airplanes)

- storage (refrigeration, warehousing)

- national defense (armies, tanks, military aircraft, manufacture of munitions)

In addition, CO

2 emitting fossil fuels many times dominate the utilities aspect of an economy that provide electricity for:

2 emitting fossil fuels many times dominate the utilities aspect of an economy that provide electricity for:

- heating & cooling

- refrigeration

- production of products

- computing and telecommunications

Peak oil may significantly affect geopolitics.

Perceived lack of adequate advanced low-carbon technologies

As of 2019 fast growing cities in developing countries lack alternatives to traditional high-carbon cement, and the hydrogen economy and carbon capture and storage are not widespread.

Industrialization of the developing world

The developing world sees economic and industrial development as a

natural right and the evidence shows that the developing world is

industrializing. The developing world is using CO

2 emitting fossil fuels as one of the primary energy sources to fuel their development. At the same time the scientific consensus on climate change and the existing global governance bodies like the United Nations are urging all countries to decrease their CO

2 emissions. Developing countries logically resist this lobbying to decrease their use of fossil fuels without significant concessions like:

2 emitting fossil fuels as one of the primary energy sources to fuel their development. At the same time the scientific consensus on climate change and the existing global governance bodies like the United Nations are urging all countries to decrease their CO

2 emissions. Developing countries logically resist this lobbying to decrease their use of fossil fuels without significant concessions like:

- advanced energy technologies

- advanced adaptation technologies

- Climate Finance.

Metric selection and perceived responsibility / ability to respond

There are significant disagreements over which metrics to use when tracking global warming and there are also disagreements over which countries should be subject to emissions restrictions.

While the biosphere is indifferent to whether the greenhouse

gases are produced by one country or by a multitude, the countries of

the world do express an interest in such matters. As such disagreements

arise on whether per capita emissions should be used or whether total

emissions should be used as a metric for each individual country.

Countries also disagree over whether a developing country should share

the same commitment as a developed country that has been emitting CO

2 and other greenhouse gases for close to a century.

2 and other greenhouse gases for close to a century.

Some developing countries expressly state that they require

assistance if they are to develop, which is seen as a right, in a

fashion that does not contribute CO

2 or other greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Many times, these needs materialize as profound differences in global conferences by countries on the subject and the debates quickly turn to pecuniary matters.

2 or other greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Many times, these needs materialize as profound differences in global conferences by countries on the subject and the debates quickly turn to pecuniary matters.

Most developing countries are unwilling to accept limits on their CO

2 and other greenhouse gas emissions while most developed countries place very modest limits on their willingness to assist developing countries.

2 and other greenhouse gas emissions while most developed countries place very modest limits on their willingness to assist developing countries.

Vulnerable developing countries and developed country legacy emissions

Some developing countries fall under the category of vulnerable to

climate change. These countries involve small, sometimes isolated,

island nations, low lying nations, nations which rely on drinking water

from shrinking glaciers etc. These vulnerable countries see themselves

as the victims of climate change and some have organized themselves

under groups like the Climate Vulnerable Forum. These countries seek climate finance

from the developed and the industrializing countries to help them adapt

to the impending catastrophes that they see climate change will bring

upon them.

For these countries climate change is seen as an existential threat and

the politics of these countries is to seek reparation and adaptation

monies from the developed world and some see it as their right.

Governance

Global warming politics focus areas

Government policies regarding climate change and many official

reports on the subject usually revolve around one of the following:

- Adaptation: social and other changes that must be undertaken to successfully adapt to climate change. Adaptation might encompass, but is not limited to, changes in agriculture and urban planning.

- Finance: how countries will finance adaptation to and mitigation of climate change, whether from public or private sources or from wealth/technology transfers from developed countries to developing countries and the management mechanisms for those monies.

- Mitigation: steps and actions that the countries of the world can take to mitigate the effects of climate change.

- Restoration: steps and actions that the countries of the world can take towards climate restoration to reduce the amount of CO2 causing the of climate change and aim at reducing global temperatures.

- Technology: the technologies that are needed lower carbon emissions through increasing energy efficiency or replacement or CO

2 emitting technologies and technologies needed to adapt or mitigate climate change. Also encompasses ways that developed countries can support developing countries in adopting new technologies or increasing efficiency. - Loss and damage: first articulated at the 2012 conference and in part based on the agreement that was signed at the 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Cancun. It introduces the principle that countries vulnerable to the effects of climate change may be financially compensated in future by countries that fail to curb their carbon emissions.

- Suppression of science: The U.S. government has also responded by silencing climate scientists and muzzling government whistleblowers. Political appointees at a number of federal agencies prevented scientists from reporting their findings, changed data modeling to arrive at conclusions they had set out a prior to prove, and shut out the input of career scientists of the agencies.

- Government Targeting of Climate Activists: Domestic intelligence services of the U.S. have targeted environmental activists and climate change organizations as "domestic terrorists," investigating them, questioning them, and placing them on national "watchlists" that could make it more difficult for them to board airplanes and could instigate local law enforcement monitoring.

- Stonewalling international cooperation: The United States has rejected international treaties, such as the Kyoto Protocol of 2005 to reduce production of greenhouse gasses, and has said that in 2020 it will withdraw from the Paris Agreement, signed by all UN member countries.

Consensus-driven global political institutions

The primary mechanism for the world to tackle global warming is through the Paris Agreement, which replaced the Kyoto Protocol in 2020, both established under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) treaty.

In 2014, the UN with Peru and France created the Global Climate Action portal for writing and checking all the climate commitments

Voluntary emissions reductions

The perceived slow process of efforts for countries to agree to a

comprehensive global level binding agreements has led some countries to

seek independent/voluntary steps and focus on alternative high-value

voluntary activities like the creation of the Climate and Clean Air Coalition to Reduce Short-Lived Climate Pollutants by the United States, Canada, Mexico, Bangladesh, and Sweden

which seeks to regulate short-lived pollutants such as methane, black

carbon and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) which together are believed to

account for up to 1/3 of current global warming but whose regulation is

not as fraught with wide economic impacts and opposition. The Climate and Clean Air Coalition to Reduce Short-Lived Climate Pollutants

(CCAC) was launched on 16 February 2012 to regulate short-lived climate

pollutants (SLCPs) that together contribute up to 1/3 of global

warming. The coalition's creation is seen as a necessary and pragmatic

step given the slow pace of global climate change agreements under the

UNFCCC.

As part of the 2010 Cancún agreements, 76 developed and developing countries have made voluntary pledges to control their emissions of greenhouse gases.

These voluntary steps are seen by some as a new model where countries

pledge to voluntarily take action against global warming outside of

international treaties or obligations to other parties. This voluntary

mechanism, while promising, does not address many of the challenges seen

by the developing world in their efforts to mitigate global warming,

adapt to global warming, and increasingly to deal with losses and

damages that they directly attribute to global warming that they blame

on the developed world's historical emissions.

National Politics

In 2019 climate change became an increasingly important political issue in Germany. On the Australian Sunday morning political discussion show The Bolt Report, Richard Lindzen said in a 2011 interview that governments might use global warming as a rationale for additional taxes.

In 2019 the highest court in the Netherlands has upheld a landmark

ruling that defines protection from the devastation of climate change as

a human right and requires the government to be more ambitious in

cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

City Politics

City politicians advocating measures which have local short-term benefits for their constituents, such as low emission zones, may also have the co-benefit of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Politics of scrapping fossil fuel subsidies

The International Monetary Fund periodically assesses global subsidies for fossil fuels

as part of its work on climate, and it found in a working paper

published in 2019, that the fossil fuel industry received $5.2 trillion

in subsidies in 2017. This amounts to 6.4 percent of the global gross

domestic product.

In line with these findings, the Central Banks of France and the United

Kingdom appealed to stop subsidies to fossil fuels and the European

Investment bank has announced it will stop financing fossil fuels

projects by the end of 2021.

According to the International Institute for Sustainable Development

most attempts to remove fossil fuel subsidies are successful and the

keys points are to: consult, compensate poor people affected by the

change, and implement step-by-step.

Politics of trees

As of 2019 the preservation of forests is emerging as a global political issue.

Special interests and lobbying by non-country interested parties

Global warming has attracted the attention of left-wing groups, as here with the Democratic Socialists of America.

There are numerous special interest groups, PACs,

organizations, corporations who have public and private positions on

the multifaceted topic of global warming. The following is a partial

list of the types of special interest parties that have demonstrated an

interest in the politics of global warming:

- Financial Institutions: Financial institutions generally support policies against global warming, particularly the implementation of carbon trading schemes and the creation of market mechanisms that associate a price with carbon. These new markets would require trading infrastructures which banking institutions are well positioned to provide. Financial institutions would also be positioned well to invest, trade and develop various financial instruments that they could profit from through speculative positions on carbon prices and the use of brokerage and other financial functions like insurance and derivative instruments.

- Environmental groups: Environmental advocacy groups generally favor strict restrictions on CO

2 emissions. Environmental groups, as activists, engage in raising awareness. - Fossil fuel companies: Traditional fossil fuel corporations

could benefit or lose from stricter global warming regulations. A

reduction in the use of fossil fuels could negatively impact fossil fuel

corporations. However, the fact that fossil fuel companies are a large source of energy, are also the primary source of CO

2, and are engaged in energy trading might mean that their participation in trading schemes and other such mechanisms might give them a unique advantage and makes it unclear whether traditional fossil fuel companies would all and always be against stricter global warming policies. As an example, Enron, a traditional gas pipeline company with a large trading desk heavily lobbied the government for the EPA to regulate CO2: they thought that they would dominate the energy industry if they could be at the center of energy trading. - Renewable energy and energy efficiency companies: companies in wind, solar and energy efficiency generally support stricter global warming policies. They would expect their share of the energy market to expand as fossil fuels are made more expensive through trading schemes or taxes.

- Nuclear energy companies: nuclear energy companies could see a renaissance in a world where fossil fuels are taxed directly or through a carbon trading mechanism. For this reason, it is likely that nuclear energy companies would support stricter global warming policies.

- Electricity distribution companies: may lose from solar panels but benefit from electric vehicles.

- Traditional retailers and marketers: traditional retailers, marketers, and the general corporations respond by adopting policies that resonate with their customers. If "being green" helps a general corporation, then they could undertake modest programs to please and better align with their customers. However, since the general corporation does not make a profit from their particular position, it is unlikely that they would strongly lobby either for or against a stricter global warming policy position.

The various interested parties sometimes align with one another to

reinforce their message. Sometimes industries will fund specialty

nonprofit organizations to raise awareness and lobby on their behest.

The combinations and tactics that the various interested parties use

are nuanced and sometimes unlimited in the variety of their approaches

to promote their positions onto the general public.

Interaction of climate science and policy

Global warming has attracted the attention of central bank governors, as here with Mark Carney, appointed UN envoy for climate action in 2019.

In the scientific literature, there is an overwhelming consensus that global surface temperatures have increased in recent decades and that the trend is caused primarily by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases.

The politicization of science in the sense of a manipulation of

science for political gains is a part of the political process. It is

part of the controversies about intelligent design (compare the Wedge strategy) or Merchants of Doubt,

scientists that are under suspicion to willingly obscure findings. e.g.

about issues like tobacco smoke, ozone depletion, global warming or

acid rain. However, e.g. in case of the Ozone depletion, global regulation based on the Montreal Protocol has been successful, in a climate of high uncertainty and against strong resistance while in case of Climate Change, the Kyoto Protocol failed.

While the IPCC process tries to find and orchestrate the findings

of global (climate) change research to shape a worldwide consensus on

the matter it has been itself been object of a strong politicization. Anthropogenic climate change evolved from a mere science issue to a top global policy topic.

The IPCC process having built a broad science consensus does not hinder governments to follow different, if not opposing goals.

In case of the ozone depletion challenge, there was global regulation

already being installed before a scientific consensus was established.

A linear model of policy-making, based on a more knowledge we have, the better the political response will be does therefore not apply. Knowledge policy,

successfully managing knowledge and uncertainties as base of political

decision making requires a better understanding of the relation between

science, public (lack of) understanding and policy instead. Michael Oppenheimer

confirms limitations of the IPCC consensus approach and asks for

concurring, smaller assessments of special problems instead of large

scale attempts as in the previous IPCC assessment reports. He claims that governments require a broader exploration of uncertainties in the future.

History

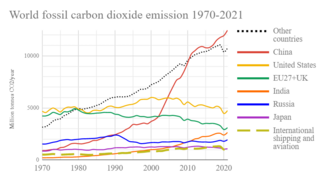

Historical annual CO2 emissions for the top six countries and confederations.

CO2 emissions per capita from 1900 to 2017.

Historically, the politics of climate change dates back to several

conferences in the late 1960s and the early 1970s under NATO and

President Richard Nixon. 1979 saw the world's first World Climate Conference. 1985 was the year that the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer was created and two years later in 1987 saw the signing of the Montreal Protocol

under the Vienna convention. This model of using a Framework

conference followed by Protocols under the Framework was seen as a

promising governing structure that could be used as a path towards a

functional governance approach that could be used to tackle broad global

multi-nation/state challenges like global warming.

One year later in 1988 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was created by the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environment Programme to assess the risk of human-induced climate change. Margaret Thatcher 1988 strongly supported IPCC and 1990 was instrumental to found the Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research in Exeter.

In 1991 the book The First Global Revolution was published by the Club of Rome

report which sought to connect environment, water availability, food

production, energy production, materials, population growth and other

elements into a blueprint for the twenty-first century: political

thinking was evolving to look at the world in terms of an integrated

global system not just in terms of weather and climate but in terms of

energy needs, food, population, etc.

1992 was the year that the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was agreed at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro

and the framework entered into force 21 March 1994. The conference

established a yearly meeting, a conference of the parties or COP meeting

to be held to continue work on Protocols which would be enforceable

treaties.

1995 saw the creation of the phrase "preventing dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system" (also called avoiding dangerous climate change) first appeared in a policy document of a governmental organization, the IPCC's Second Assessment Report: Climate Change 1995. and in 1996 the European Union adopt a goal of limiting temperature rises to a maximum 2 °C rise in average global temperature.

In 1997 the Kyoto Protocol was created under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in a very similar structure as the Montreal Protocol was under the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer which would have yearly meetings of the members or CMP meetings. However, in the same year, the US Senate passed Byrd–Hagel Resolution rejecting Kyoto without more commitments from developing countries.

Since the 1992 UNFCCC

treaty, eighteen COP sessions and eight CMP sessions have been held

under the existing structure. In that time, global CO2 emissions have

risen significantly and developing countries have grown significantly

with China replacing the United States

as the largest emitter of greenhouse gases. To some, the UNFCCC has

made significant progress in helping the world become aware of the

perils of global warming and has moved the world forward in the

addressing of the challenge. To others, the UNFCCC process has been a

failure due to its inability to control the rise of greenhouse gas

emissions.

A number of proposals for a Global Climate Regime are currently discussed, as the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action calls for a comprehensive new agreement in 2015 that includes both Annex-I and Non-Annex-I parties.

Selective historical timeline of significant climate change political events

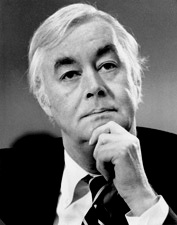

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, pioneer of the political treatment of the greenhouse effect

- 1969, on Initiative of US President Richard Nixon, NATO tried to establish a third civil column and planned to establish itself as a hub of research and initiatives in the civil region, especially on environmental topics. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Nixons NATO delegate for the topic named acid rain and the greenhouse effect as suitable international challenges to be dealt by NATO. NATO had suitable expertise in the field, experience with international research coordination and a direct access to governments. After an enthusiastic start on authority level, the German government reacted skeptically. The initiative was seen as an American attempt to regain international terrain after the lost Vietnam War. The topics and the internal coordination and preparation effort however gained momentum in civil conferences and institutions in Germany and beyond during the Brandt government.

- 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, leading role of Nobel Prize winner Willy Brandt and Olof Palme, Germany saw enhanced international research cooperation on the greenhouse topic as necessary

- 1978 Brandt Report, the greenhouse effect dealt with in the energy section

- 1979: First World Climate Conference

- 1987: Brundtland Report

- 1987: Montreal Protocol on restricting ozone layer-damaging CFCs demonstrates the possibility of coordinated international action on global environmental issues.

- 1988: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change set up to coordinate scientific research, by two United Nations organizations, the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to assess the "risk of human-induced climate change".

- 1992: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was formed to "prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system"

- 1996: European Union adopts target of a maximum 2 °C rise in average global temperature

- 25 June 1997: US Senate passes Byrd–Hagel Resolution rejecting Kyoto without more commitments from developing countries

- 1997: Kyoto Protocol agreed

- 2001: George W. Bush withdraws from the Kyoto negotiations

- 16 February 2005: Kyoto Protocol comes into force (not including the US or Australia)

- 2005: the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme is launched, the first such scheme

- July 2005: 31st G8 summit has climate change on the agenda, but makes relatively little concrete progress

- November/December 2005: United Nations Climate Change Conference; the first meeting of the Parties of the Kyoto Protocol, alongside the 11th Conference of the Parties (COP11), to plan further measures for 2008–2012 and beyond.

- 30 October 2006: The Stern Review

is published. It is the first comprehensive contribution to the global

warming debate by an economist and its conclusions lead to the promise

of urgent action by the UK government to further curb Europe's CO

2 emissions and engage other countries to do so. It discusses the consequences of climate change, mitigation measures to prevent it, possible adaptation measures to deal with its consequences, and prospects for international cooperation. - 26 June 2009: US House of Representatives passes the American Clean Energy and Security Act, the "first time either house of Congress had approved a bill meant to curb the heat-trapping gases scientists have linked to climate change."

- 12 December 2015: World leaders meet in Paris, France for the 21st Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC. One hundred eighty seven countries eventually signed on to the Paris Agreement. As of September 2016, 187 UNFCCC members have signed the treaty, 60 of which have ratified it. The agreement will only enter into force provided that 55 countries that produce at least 55% of the world's greenhouse gas emissions ratify, accept, approve or accede to the agreement; although the minimum number of ratifications has been reached, the ratifying states do not produce the requisite percentage of greenhouse gases for the agreement to enter into force.