Behavioural genetics, also referred to as behaviour genetics, is a field of scientific research that uses genetic methods to investigate the nature and origins of individual differences in behaviour. While the name "behavioural genetics" connotes a focus on genetic influences, the field broadly investigates genetic and environmental influences, using research designs that allow removal of the confounding of genes and environment. Behavioural genetics was founded as a scientific discipline by Francis Galton in the late 19th century, only to be discredited through association with eugenics movements before and during World War II. In the latter half of the 20th century, the field saw renewed prominence with research on inheritance of behaviour and mental illness in humans (typically using twin and family studies), as well as research on genetically informative model organisms through selective breeding and crosses. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, technological advances in molecular genetics made it possible to measure and modify the genome directly. This led to major advances in model organism research (e.g., knockout mice) and in human studies (e.g., genome-wide association studies), leading to new scientific discoveries.

Findings from behavioural genetic research have broadly impacted modern understanding of the role of genetic and environmental influences on behaviour. These include evidence that nearly all researched behaviors are under a significant degree of genetic influence, and that influence tends to increase as individuals develop into adulthood. Further, most researched human behaviours are influenced by a very large number of genes and the individual effects of these genes are very small. Environmental influences also play a strong role, but they tend to make family members more different from one another, not more similar.

History

Selective breeding and the domestication

of animals is perhaps the earliest evidence that humans considered the

idea that individual differences in behaviour could be due to natural

causes. Plato and Aristotle each speculated on the basis and mechanisms of inheritance of behavioural characteristics. Plato, for example, argued in The Republic

that selective breeding among the citizenry to encourage the

development of some traits and discourage others, what today might be

called eugenics, was to be encouraged in the pursuit of an ideal society. Behavioural genetic concepts also existed during the English renaissance, where William Shakespeare perhaps first coined the terms "nature" versus "nurture" in The Tempest, where he wrote in Act IV, Scene I, that Caliban was "A devil, a born devil, on whose nature Nurture can never stick".

Modern-day behavioural genetics began with Sir Francis Galton, a nineteenth-century intellectual and cousin of Charles Darwin. Galton was a polymath who studied many subjects, including the heritability of human abilities and mental characteristics. One of Galton's investigations involved a large pedigree study of social and intellectual achievement in the English upper class. In 1869, 10 years after Darwin's On the Origin of Species, Galton published his results in Hereditary Genius.

In this work, Galton found that the rate of "eminence" was highest

among close relatives of eminent individuals, and decreased as the

degree of relationship to eminent individuals decreased. While Galton

could not rule out the role of environmental influences on eminence, a

fact which he acknowledged, the study served to initiate an important

debate about the relative roles of genes and environment on behavioural characteristics. Through his work, Galton also "introduced multivariate analysis and paved the way towards modern Bayesian statistics" that are used throughout the sciences—launching what has been dubbed the "Statistical Enlightenment".

Galton in his later years

The field of behavioural genetics, as founded by Galton, was

ultimately undermined by another of Galton's intellectual contributions,

the founding of the eugenics movement in 20th century society. The primary idea behind eugenics was to use selective breeding combined with knowledge about the inheritance of behaviour to improve the human species. The eugenics movement was subsequently discredited by scientific corruption and genocidal actions in Nazi Germany. Behavioural genetics was thereby discredited through its association to eugenics.

The field once again gained status as a distinct scientific discipline

through the publication of early texts on behavioural genetics, such as Calvin S. Hall's 1951 book chapter on behavioural genetics, in which he introduced the term "psychogenetics", which enjoyed some limited popularity in the 1960s and 1970s. However, it eventually disappeared from usage in favour of "behaviour genetics".

The start of behavior genetics as a well-identified field was marked by the publication in 1960 of the book Behavior Genetics by John L. Fuller and William Robert (Bob) Thompson.

It is widely accepted now that many if not most behaviours in animals

and humans are under significant genetic influence, although the extent

of genetic influence for any particular trait can differ widely. A decade later, in February 1970, the first issue of the journal Behavior Genetics was published and in 1972 the Behavior Genetics Association was formed with Theodosius Dobzhansky elected as the association's first president. The field has since grown and diversified, touching many scientific disciplines.

Methods

The primary goal of behavioural genetics is to investigate the nature and origins of individual differences in behaviour. A wide variety of different methodological approaches are used in behavioral genetic research, only a few of which are outlined below.

Animal studies

Animal behavior genetic studies are considered more reliable than are

studies on humans, because animal experiments allow for more variables

to be manipulated in the laboratory. In animal research selection experiments have often been employed. For example, laboratory house mice have been bred for open-field behaviour, thermoregulatory nesting, and voluntary wheel-running behaviour. A range of methods in these designs are covered on those pages.

Behavioural geneticists using model organisms employ a range of molecular techniques to alter, insert, or delete genes. These techniques include knockouts, floxing, gene knockdown, or genome editing using methods like CRISPR-Cas9.

These techniques allow behavioural geneticists different levels of

control in the model organism's genome, to evaluate the molecular, physiological, or behavioural outcome of genetic changes. Animals commonly used as model organisms in behavioral genetics include mice, zebra fish, and the nematode species C. elegans.

Twin and family studies

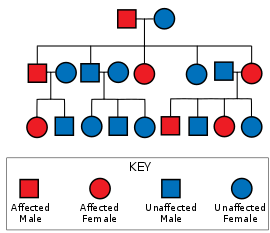

Pedigree chart showing an inheritance pattern consistent with autosomal dominant transmission. Behavioural geneticists have used pedigree studies to investigate the genetic and environmental basis of behaviour.

Some research designs used in behavioural genetic research are variations on family designs (also known as pedigree designs), including twin studies and adoption studies. Quantitative genetic modelling of individuals with known genetic relationships (e.g., parent-child, sibling, dizygotic and monozygotic twins) allows one to estimate to what extent genes and environment contribute to phenotypic differences among individuals. The basic intuition of the twin study is that monozygotic twins share 100% of their genome and dizygotic

twins share, on average, 50% of their segregating genome. Thus,

differences between the two members of a monozygotic twin pair can only

be due to differences in their environment, whereas dizygotic twins will

differ from one another due to environment as well as genes. Under this

simplistic model, if dizygotic twins differ more than monozygotic twins

it can only be attributable to genetic influences. An important

assumption of the twin model is the equal environment assumption

that monozygotic twins have the same shared environmental experiences

as dizygotic twins. If, for example, monozygotic twins tend to have more

similar experiences than dizygotic twins—and these experiences

themselves are not genetically mediated through gene-environment correlation

mechanisms—then monozygotic twins will tend to be more similar to one

another than dizygotic twins for reasons that have nothing to do with

genes.

Twin studies of monozygotic and dizygotic twins use a biometrical

formulation to describe the influences on twin similarity and to infer

heritability.

The formulation rests on the basic observation that the variance in a phenotype is due to two sources, genes and environment. More formally, , where is the phenotype, is the effect of genes, is the effect of the environment, and is a gene by environment interaction. The term can be expanded to include additive (), dominance (), and epistatic () genetic effects. Similarly, the environmental term can be expanded to include shared environment () and non-shared environment (), which includes any measurement error. Dropping the gene by environment interaction for simplicity (typical in twin studies) and fully decomposing the and terms, we now have .

Twin research then models the similarity in monozygotic twins and

dizogotic twins using simplified forms of this decomposition, shown in

the table.

| Type of relationship | Full decomposition | Falconer's decomposition |

|---|---|---|

| Perfect similarity between siblings | ||

| Monozygotic twin correlation() | ||

| Dizygotic twin correlation () | ||

|

| ||

| Where is an unknown (probably very small) quantity. | ||

The simplified Falconer formulation can then be used to derive estimates of , , and . Rearranging and substituting the and equations one can obtain an estimate of the additive genetic variance, or heritability, , the non-shared environmental effect and, finally, the shared environmental effect . The Falconer formulation is presented here to illustrate how the twin model works. Modern approaches use maximum likelihood to estimate the genetic and environmental variance components.

Measured genetic variants

The Human Genome Project has allowed scientists to directly genotype the sequence of human DNA nucleotides. Once genotyped, genetic variants can be tested for association with a behavioural phenotype, such as mental disorder, cognitive ability, personality, and so on.

- Candidate Genes. One popular approach has been to test for association candidate genes with behavioural phenotypes, where the candidate gene is selected based on some a priori theory about biological mechanisms involved in the manifestation of a behavioural trait or phenotype. In general, such studies have proven difficult to broadly replicate and there has been concern raised that the false positive rate in this type of research is high.

- Genome-wide association studies. In genome-wide association studies, researchers test the relationship of millions of genetic polymorphisms with behavioural phenotypes across the genome. This approach to genetic association studies is largely atheoretical, and typically not guided by a particular biological hypothesis regarding the phenotype. Genetic association findings for behavioural traits and psychiatric disorders have been found to be highly polygenic (involving many small genetic effects).

- SNP heritability and co-heritability. Recently, researchers have begun to use similarity between classically unrelated people at their measured single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to estimate genetic variation or covariation that is tagged by SNPs, using mixed effects models implemented in software such as Genome-wide complex trait analysis (GCTA). To do this, researchers find the average genetic relatedness over all SNPs between all individuals in a (typically large) sample, and use Haseman-Elston regression or restricted maximum likelihood to estimate the genetic variation that is "tagged" by, or predicted by, the SNPs. The proportion of phenotypic variation that is accounted for by the genetic relatedness has been called "SNP heritability". Intuitively, SNP heritability increases to the degree that phenotypic similarity is predicted by genetic similarity at measured SNPs, and is expected to be lower than the true narrow-sense heritability to the degree that measured SNPs fail to tag (typically rare) causal variants. The value of this method is that it is an independent way to estimate heritability that does not require the same assumptions as those in twin and family studies, and that it gives insight into the allelic frequency spectrum of the causal variants underlying trait variation.

Quasi-experimental designs

Some behavioural genetic designs are useful not to understand genetic influences on behaviour, but to control for genetic influences to test environmentally-mediated influences on behaviour. Such behavioural genetic designs may be considered a subset of natural experiments, quasi-experiments that attempt to take advantage of naturally occurring situations that mimic true experiments by providing some control over an independent variable. Natural experiments can be particularly useful when experiments are infeasible, due to practical or ethical limitations.

A general limitation of observational studies is that the relative influences of genes and environment are confounded. A simple demonstration of this fact is that measures of 'environmental' influence are heritable. Thus, observing a correlation

between an environmental risk factor and a health outcome is not

necessarily evidence for environmental influence on the health outcome.

Similarly, in observational studies

of parent-child behavioural transmission, for example, it is impossible

to know if the transmission is due to genetic or environmental

influences, due to the problem of passive gene-environment correlation. The simple observation that the children of parents who use drugs are more likely to use drugs as adults does not indicate why the children are more likely to use drugs when they grow up. It could be because the children are modelling

their parents' behaviour. Equally plausible, it could be that the

children inherited drug-use-predisposing genes from their parent, which

put them at increased risk for drug use as adults regardless of their

parents' behaviour. Adoption studies, which parse the relative effects

of rearing environment and genetic inheritance, find a small to

negligible effect of rearing environment on smoking, alcohol, and marijuana use in adopted children, but a larger effect of rearing environment on harder drug use.

Other behavioural genetic designs include discordant twin studies, children of twins designs, and Mendelian randomization.

General findings

There are many broad conclusions to be drawn from behavioural genetic research about the nature and origins of behaviour.

Three major conclusions include: 1) all behavioural traits and

disorders are influenced by genes; 2) environmental influences tend to

make members of the same family more different, rather than more

similar; and 3) the influence of genes tends to increase in relative

importance as individuals age.

Genetic influences on behaviour are pervasive

It is clear from multiple lines of evidence that all researched behavioural traits and disorders are influenced by genes; that is, they are heritable. The single largest source of evidence comes from twin studies, where it is routinely observed that monozygotic (identical) twins are more similar to one another than are same-sex dizygotic (fraternal) twins.

The conclusion that genetic influences are pervasive has also

been observed in research designs that do not depend on the assumptions

of the twin method. Adoption studies show that adoptees

are routinely more similar to their biological relatives than their

adoptive relatives for a wide variety of traits and disorders. In the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart, monozygotic twins separated shortly after birth were reunited in adulthood.

These adopted, reared-apart twins were as similar to one another as

were twins reared together on a wide range of measures including general

cognitive ability, personality, religious attitudes, and vocational interests, among others. Approaches using genome-wide genotyping

have allowed researchers to measure genetic relatedness between

individuals and estimate heritability based on millions of genetic

variants. Methods exist to test whether the extent of genetic similarity

(aka, relatedness) between nominally unrelated individuals (individuals

who are not close or even distant relatives) is associated with

phenotypic similarity.

Such methods do not rely on the same assumptions as twin or adoption

studies, and routinely find evidence for heritability of behavioural

traits and disorders.

Nature of environmental influence

Just as all researched human behavioural phenotypes are influenced by genes (i.e., are heritable), all such phenotypes are also influenced by the environment. The basic fact that monozygotic twins are genetically identical but are never perfectly concordant for psychiatric disorder or perfectly correlated for behavioural traits, indicates that the environment shapes human behaviour.

The nature of this environmental influence, however, is such that

it tends to make individuals in the same family more different from one

another, not more similar to one another. That is, estimates of shared environmental effects ()

in human studies are small, negligible, or zero for the vast majority

of behavioural traits and psychiatric disorders, whereas estimates of

non-shared environmental effects () are moderate to large. From twin studies is typically estimated at 0 because the correlation () between monozygotic twins is at least twice the correlation () for dizygotic twins. When using the Falconer variance decomposition () this difference between monozygotic and dizygotic twin similarity results in an estimated . It is important to note that the Falconer decomposition is simplistic.

It removes the possible influence of dominance and epistatic effects

which, if present, will tend to make monozygotic twins more similar than

dizygotic twins and mask the influence of shared environmental effects. This is a limitation of the twin design for estimating . However, the general conclusion that shared environmental effects are negligible does not rest on twin studies alone. Adoption research also fails to find large ()

components; that is, adoptive parents and their adopted children tend

to show much less resemblance to one another than the adopted child and

his or her non-rearing biological parent.

In studies of adoptive families with at least one biological child and

one adopted child, the sibling resemblance also tends be nearly zero for

most traits that have been studied.

Similarity in twins and adoptees indicates a small role for shared environment in personality.

The figure provides an example from personality

research, where twin and adoption studies converge on the conclusion of

zero to small influences of shared environment on broad personality

traits measured by the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire including positive emotionality, negative emotionality, and constraint.

Given the conclusion that all researched behavioural traits and

psychiatric disorders are heritable, biological siblings will always

tend to be more similar to one another than will adopted siblings.

However, for some traits, especially when measured during adolescence,

adopted siblings do show some significant similarity (e.g., correlations

of .20) to one another. Traits that have been demonstrated to have

significant shared environmental influences include internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, substance use and dependence, and intelligence.

Nature of genetic influence

Genetic effects on human behavioural outcomes can be described in multiple ways. One way to describe the effect is in terms of how much variance in the behaviour can be accounted for by alleles in the genetic variant, otherwise known as the coefficient of determination or . An intuitive way to think about

is that it describes the extent to which the genetic variant makes

individuals, who harbour different alleles, different from one another

on the behavioural outcome.

A complementary way to describe effects of individual genetic variants

is in how much change one expects on the behavioural outcome given a

change in the number of risk alleles an individual harbours, often

denoted by the Greek letter (denoting the slope in a regression equation), or, in the case of binary disease outcomes by the odds ratio of disease given allele status. Note the difference: describes the population-level effect of alleles within a genetic variant; or

describe the effect of having a risk allele on the individual who

harbours it, relative to an individual who does not harbour a risk

allele.

When described on the metric, the effects of individual genetic variants on complex human behavioural traits and disorders are vanishingly small, with each variant accounting for of variation in the phenotype. This fact has been discovered primarily through genome-wide association studies of complex behavioural phenotypes, including results on substance use, personality, fertility, schizophrenia, depression, and endophenotypes including brain structure and function. There are a small handful of replicated and robustly studied exceptions to this rule, including the effect of APOE on Alzheimer's disease, and CHRNA5 on smoking behaviour, and ALDH2 (in individuals of East Asian ancestry) on alcohol use.

On the other hand, when assessing effects according to the

metric, there are a large number of genetic variants that have very

large effects on complex behavioural phenotypes. The risk alleles within

such variants are exceedingly rare, such that their large behavioural

effects impact only a small number of individuals. Thus, when assessed

at a population level using the

metric, they account for only a small amount of the differences in risk

between individuals in the population. Examples include variants within

APP that result in familial forms of severe early onset Alzheimer's disease but affect only relatively few individuals. Compare this to risk alleles within APOE, which pose much smaller risk compared to APP, but are far more common and therefore affect a much greater proportion of the population.

Finally, there are classical behavioural disorders that are genetically simple in their etiology, such as Huntington's disease. Huntington's is caused by a single autosomal dominant variant in the HTT

gene, which is the only variant that accounts for any differences among

individuals in their risk for developing the disease, assuming they

live long enough. In the case of genetically simple and rare diseases such as Huntington's, the variant and the are simultaneously large.

Additional general findings

In response to general concerns about the replicability of psychological research, behavioral geneticists Robert Plomin, John C. DeFries, Valerie Knopik, and Jenae Neiderhiser published a review of the ten most well-replicated findings from behavioral genetics research. The ten findings were:

- "All psychological traits show significant and substantial genetic influence."

- "No traits are 100% heritable."

- "Heritability is caused by many genes of small effect."

- "Phenotypic correlations between psychological traits show significant and substantial genetic mediation."

- "The heritability of intelligence increases throughout development."

- "Age-to-age stability is mainly due to genetics."

- "Most measures of the 'environment' show significant genetic influence."

- "Most associations between environmental measures and psychological traits are significantly mediated genetically."

- "Most environmental effects are not shared by children growing up in the same family."

- "Abnormal is normal."

Criticisms and controversies

Behavioural

genetic research and findings have at times been controversial. Some of

this controversy has arisen because behavioural genetic findings can

challenge societal beliefs about the nature of human behaviour and abilities. Major areas of controversy have included genetic research on topics such as racial differences, intelligence, violence, and human sexuality. Other controversies have arisen due to misunderstandings of behavioural genetic research, whether by the lay public or the researchers themselves.

For example, the notion of heritability is easily misunderstood to

imply causality, or that some behavior or condition is determined by

one's genetic endowment.

When behavioral genetics researchers say that a behavior is X%

heritable, that does not mean that genetics causes, determines, or fixes

up to X% of the behavior. Instead, heritability is a statement about

population level correlations.

Historically, perhaps the most controversial subject has been on race and genetics, where fringe research

groups have claimed that observed racial differences on a behavioral

trait are a product of racial differences in allele frequencies. Such

claims are made most frequently to differences between White and Black

racial groups. These are complicated issues that are extremely difficult

to resolve due to the confounding of the racial group and environmental

experience, such as discrimination and oppression. Indeed, race is a social construct that is not very useful for genetic research. Instead, geneticists use concepts such as ancestry, which is more rigorously defined. For example, a so-called "Black" race may include all individuals of relatively recent African descent ("recent" because all humans are descended from African ancestors). However, there is more genetic diversity in Africa than the rest of the world combined, so speaking of a "Black" race is without a precise genetic meaning.

Qualitative research has fostered arguments that behavioural genetics is an ungovernable field without scientific norms or consensus, which fosters controversy.

The argument continues that this state of affairs has led to

controversies including race, intelligence, instances where variation

within a single gene was found to very strongly influence a

controversial phenotype (e.g., the "gay gene"

controversy), and others. This argument further states that because of

the persistence of controversy in behavior genetics and the failure of

disputes to be resolved, behavior genetics does not conform to the

standards of good science.

The scientific assumptions on which parts of behavioral genetic research are based have also been criticized as flawed. Genome wide association studies are often implemented with simplifying statistical assumptions, such as additivity,

which may be statistically robust but unrealistic for some behaviors.

Critics further contend that, in humans, behavior genetics represents a

misguided form of genetic reductionism based on inaccurate interpretations of statistical analyses. Studies comparing monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twins assume that environmental influences will be the same in both types of twins, but this assumption may also be unrealistic. In reality MZ twins are treated more alike than DZ twins, which itself may be an example of evocative gene-environment correlation,

suggesting that one's genes influence their treatment by others. It is

also not possible in twin studies to completely eliminate effects of the

shared womb environment, although studies comparing twins who

experience monochorionic and dichorionic environments in utero do exist, and indicate limited impact. Studies of twins separated in early life include children who were separated not at birth but part way through childhood.

The effect of early rearing environment can therefore be evaluated to

some extent in such a study, by comparing twin similarity for those

twins separated early and those separated later.