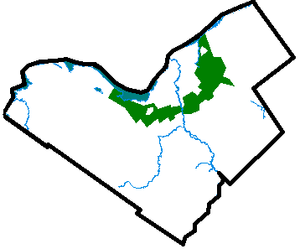

The central core of Ottawa, located in the middle of the map, is surrounded by the Ottawa Greenbelt

A greenbelt is a policy and land use zone designation used in land use planning to retain areas of largely undeveloped, wild, or agricultural land surrounding or neighboring urban areas. Similar concepts are greenways or green wedges

which have a linear character and may run through an urban area instead

of around it. In essence, a green belt is an invisible line designating

a border around a certain area, preventing development of the area and

allowing wildlife to return and be established.

Purposes

In those countries which have them, the stated objectives of green belt policy are to:

- Protect natural or semi-natural environments;

- Improve air quality within urban areas;

- Ensure that urban dwellers have access to countryside, with consequent educational and recreational opportunities; and

- Protect the unique character of rural communities that might otherwise be absorbed by expanding suburbs.

The green belt has many benefits for people:

- Walking, camping, and biking areas close to the cities and towns.

- Contiguous habitat network for wild plants, animals and wildlife.

- Cleaner air and water

- Better land use of areas within the bordering cities.

The effectiveness of green belts differs depending on location and country. They can often be eroded by urban rural fringe

uses and sometimes, development 'jumps' over the green belt area,

resulting in the creation of "satellite towns" which, although separated

from the city by green belt, function more like suburbs than

independent communities.

History

The Old Testament outlines a proposal for a green belt around the Levite towns in the Land of Israel. Moses Maimonides expounded that the greenbelt plan from the Old Testament referred to all towns in ancient Israel. In the 7th century, Muhammad established a green belt around Medina. He did this by prohibiting any further removal of trees in a 12-mile long strip around the city. In 1580 Elizabeth I of England banned new building in a 3-mile wide belt around the City of London

in an attempt to stop the spread of plague. However, this was not

widely enforced and it was possible to buy dispensations which reduced

the effectiveness of the proclamation.

In modern times, the term emerged from continental Europe where

broad boulevards were increasingly used to separate new development from

the centre of historic towns; most notably the Ringstraße in Vienna. Green belt policy was then pioneered in the United Kingdom confronted with ongoing rural flight. Various proposals were put forward from 1890 onwards but the first to garner widespread support was put forward by the London Society in its "Development Plan of Greater London" 1919. Alongside the CPRE they lobbied for a continuous belt (of up to two miles wide) to prevent urban sprawl, beyond which new development could occur.

There are fourteen green belt areas in the UK covering 16,716 km² or 13% of England, and 164 km² of Scotland; for a detailed discussion of these, see Green belt (UK). Other notable examples are the Ottawa Greenbelt and Golden Horseshoe Greenbelt in Ontario, Canada. Ottawa's 20,350-hectare (78.6 sq mi) instance is managed by the National Capital Commission (NCC). The more general term in the United States is green space or greenspace, which may be a very small area such as a park.

The dynamic Adelaide Park Lands, measuring approximately 7.6 km² surround, unbroken, the city centre of Adelaide. On the fringe of the eastern suburbs, an expansive natural greenbelt in the Adelaide Hills acts as a growth boundary for Adelaide and cools the city in the hottest months.

The concept of "green belt" has evolved in recent years to

encompass not only "Greenspace" but also "Greenstructure" which

comprises all urban and peri-urban greenspaces, an important aspect of

sustainable development in the 21st century. The European Commission's COST Action C11

(COST – European Cooperation in Science and Technology) is undertaking

"Case studies in Greenstructure Planning" involving 15 European countries.

An act of the Swedish parliament from 1994 has declared a series of parks in Stockholm and the adjacent municipality of Solna to its north a "national city park" called Royal National City Park.

Criticism

House prices

When

paired with a city which is economically prospering, homes in a Green

belt may have been motivated by or result in considerable premiums. They

may also be more economically resilient as popular among the retired

and less attractive for short-term renting of modest homes.

Where in the city itself demand exceeds supply in housing, green belt

homes compete directly with much city housing wherever such green belt

homes are well-connected to the city.

Further, they in all cases attract a future-guaranteed premium for

protection of their views, recreational space and for the

preservation/conservation value itself. Most also benefit from higher rates of urban gardening and farming, particularly when done in a community setting, which have positive effects on nutrition, fitness, self-esteem,

and happiness, providing a benefit for both physical and mental health,

in all cases easily provided or accessed in a green belt. Government planners also seek to protect the green belt as its local farmers are engaged in peri-urban agriculture which augments carbon sequestration, reduces the urban heat island effect, and provides a habitat for organisms. Peri-urban agriculture may also help recycle urban greywater and other products of wastewater, helping to conserve water and reduce waste.

The housing market contrasts with more uncertainty and economic liberalism inside and immediately outside of the belt: Green Belt homes have by definition nearby protected landscapes. Local residents in affluent parts of a Green Belt, as in parts of the city, can be assured of preserving any localised bourgeois status quo present and so assuming the Green Belt is not from the outset an area of more social housing

proportionately than the city, it naturally tends toward greater

economic wealth. In a protracted housing shortage, reduction of the

Green Belt is one of the possible solutions. All such solutions may be

resisted however by private landlords

who profit from a scarcity of housing, for example by lobbying to

restrain new housing across the city. The stated motivation and benefits

of the green belt might be well-intentioned (public health, social

gardening and agriculture, environment), but inadequately realised

relative to other solutions.

Inherently partial critics include Mark Pennington and the economics-heavy think tanks such as the Institute of Economic Affairs who would see a reduction in many Green Belts. Such studies focus on widely inherent limitations of Green Belts. In most examples only a small fraction of the population uses the green belt for leisure purposes. The IEA study claims that a green belt is not strongly causally linked to clean air and water.

Rather, they view the ultimate result of the decision to green-belt a

city as one to prevent housing demand within the zone to be met with

supply, thus exacerbating high housing prices and stifling competitive forces in general.

Increasing urban sprawl

Another

area of criticism comes from the fact that, since a greenbelt does not

extend indefinitely outside a city, it spurs the growth of areas much

further away from the city core than if it had not existed, thereby

actually increasing urban sprawl. Examples commonly cited are the Ottawa suburbs of Kanata and Orleans, both of which are outside the city's greenbelt, and are currently undergoing explosive growth (see Greenbelt (Ottawa)).

This leads to other problems, as residents of these areas have a longer

commute to work places in the city and worse access to public transport.

It also means people have to commute through the green belt, an area

not designed to cope with high levels of transportation. Not only is the

merit of a green belt subverted, but the green belt may heighten the

problem and make the city unsustainable.

There are many examples whereby the actual effect of green belts

is to act as a land reserve for future freeways and other highways.

Examples include sections of the 407 highway north of Toronto and the

Hunt Club Rd./Richmond Rd. south of Ottawa. Whether they are originally

planned as such, or the result of a newer administration taking

advantage of land that was left available by its predecessors is

debatable.

United Kingdom

Green belts were established in England from 1955 to simply prevent

the physical growth of large built-up areas; to prevent neighboring

cities and towns from merging.

In the UK, greenbelt around the major conurbations has been criticized

as one of the main protectionist bars to building housing, the others

being other planning restrictions (Local Plans and restrictive covenants) and developers' land banking.

Local Plans and land banking are to be relaxed for home building in the

2015-2030 period by law and the green belt will be reduced by some

local authorities as each local authority must now consider it among the

available shortlisted options in drawing development plans to meet

higher housing targets. Critics argue that the greenbelts defeat their

stated objective of saving the countryside and open spaces. Such

criticism falls short when considering the other, broader benefits such

as peri-urban agriculture which includes gardening and carries many benefits, especially to the retired. It also ignores the strategic aims of the Attlee Ministry

in 1946, just as in France, of shifting capital away from the capital

city (addressing regional disparity) and avoiding intra-urban gridlock.

The restrictions of the Green Belt were particularly in the 1940s-1980s

mitigated with planned, government-supported, new towns under the New Towns Act 1946 and New Towns Act 1981. These saw establishment beyond the greenbelts of new homes, infrastructure, businesses and other facilities. Without large scale sustainable development, infill development

sees urban green space lost. A chronic housing shortage with inadequate

new settlements and/or extension of those outside of the green belt

and/or no green belt reduction has seen many brownfield sites, often

well-suited to industry and commerce, lost in existing conurbations.

Notable examples

Australia

- Adelaide's Central Business District is completely encircled by the Adelaide Parklands, as was initially planned in 1837.

- The Nillumbik Shire Council which is located approximately 30 km (19 miles) north-east of Melbourne is considered as "The Green Wedge Shire" because of the agreement with the Victorian Government which prevents high-density infrastructure to be built.

Brazil

- The São Paulo City Green Belt Biosphere Reserve – GBBR, an integral part of the Atlantic Forest Biosphere Reserve, was created in 1994 stemming from a people's movement that collected 150 thousand signatures. It extends throughout 73 municipalities including São Paulo metro and the Santos area. With approximately 17,000 km², it is inhabited by about 23 million people, corresponding to more than 10% of the country's total population in an area equivalent to 0.2% of the Brazilian territory. There are over 6,000 km² of forests and other Atlantic Forest ecosystems at the Reserve, one of the planet's most threatened biomes. In addition to a spectacular biological diversity, the GBBR's ecosystems render valuable ecosystem services.

Canada

- Ottawa Greenbelt, is Canada's oldest greenbelt. Created in 1956 to help curb urban sprawl, it surrounds the capital city of Ottawa. It is mostly owned and managed by the National Capital Commission (NCC).

- Greenbelt (Golden Horseshoe), is a 7300 km² band of land that encompasses the rural and agricultural land surrounding the Greater Toronto Area and Niagara Peninsula, and parts of the Bruce Peninsula. Most of the land consists of the Oak Ridges Moraine, an environmentally sensitive land that is a major aquifer for the region, and the Niagara Escarpment, a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. In an effort to restrain urban sprawl, the Ontario government created the Greenbelt Act in February 2005 to protect this greenspace from all future development, with the exception of limited agricultural use.

- British Columbia – the Agricultural Land Reserve protects agricultural land throughout this mountainous province from urban development, including around Vancouver. This protection is strict and urban development of agricultural land is only allowed if no reasonable alternative exists. However, it does not protect non-agricultural land, particularly hillsides, leading to substantial, and highly visible, leapfrog-type hillside sprawl.

- Quebec – The Commission de protection du territoire agricole du Québec asserts its mission, namely to keep a territory (the agricultural zones) that is favorable for the practice and the development of agricultural activities. In so doing, the commission safeguards the agricultural territory and helps make its protection a local priority. The agricultural zones cover an area of 63 000 square kilometres in 952 local municipalities.

Dominican Republic

- The Greater Santo Domingo has a Greenbelt (Santo Domingo Greenbelt) project surrounding the whole Distrito Nacional. It is composed of the National botanical Garden, Mirador Del Norte, Mirador del Este, and other parks surrounding the area from its outer municipios. It has largely been affected by uncontrolled urbanization, but other parts remain unaffected.[16][17]

Iran

- Green Belt in Tehran has always been a consequential matter due to the rapid increase of the city size, population, cars, factories, pollution and other expansions which hardened breathing. By a big project, the green belt of Tehran increased from 29 square kilometres in 1979 to 530 square kilometres in 2017 and the number of parks also increased from 75 in 1979 to 2,211 in 2017 in total urban and suburb areas. Such actions and afforestation increased the humidity level and precipitation chance in the city which cools the summer's temperatures down by up to 4 °C. Tehran municipality announced to increase the green belt by 10 square kilometres each year.

Mainland Europe

Rennes Green Belt

- European Green Belt

- Banjica Forest, Belgrade

- Royal National City Park, Stockholm

- German Green Belt

- Inner and Outer Green Belt of Cologne

- Coulée verte du sud parisien

- Coulée verte du nord parisien

- Promenade plantée

- Vienna Woods, Austria

- Rennes Green Belt, France

- Parco Agricolo Sud Milano, Milan

New Zealand

In New Zealand, the term Town Belt is most commonly used for an urban green belt.

- Dunedin Town Belt is one of the world's oldest green belts, having been planned at the time of the city's rapid growth during the Otago Gold Rush of the 1860s. It surrounds the city centre on three sides (the fourth side being the city's harbour).

- Hamilton Town Belt

- Wellington Town Belt

Philippines

- Makati City's green belt is very green yet full of malls and modern structures.

Thailand

- Bangkok's Bang Krachao Green Area located inside the curve of Chao Phraya River is considered a green area with authority control over the urbanization. Today it is a popular spot for tourism and cycling. The area is located within the border of Bangkok Province and Samut Sakorn Province.

South Korea

- It was first introduced as Limited Development Area in 1971 with City Planning Law to prevent urban sprawl around Seoul. Currently green belts are designated around Seoul, Busan and other metropolitan areas around the country.

United Kingdom

Designated areas of green belt in England; the Metropolitan Green Belt outlined in red

- The Metropolitan Green Belt (5,100 km²)

- The North West Green Belt (2,600 km²)

- South and West Yorkshire Green Belt (2,600 km²)

- West Midlands Green Belt (2,300 km²)

United States

- The U.S. states of Oregon, Washington and Tennessee require cities to establish urban growth boundaries (UGBs).

- Notable U.S. cities which have adopted UGBs include Portland, Oregon; Twin Cities, Minnesota; Virginia Beach, Virginia; Lexington, Kentucky (US's first in 1958[20]); and Miami-Dade County, Florida.

- The Public Works Administration of the New Deal created three Greenbelt communities based on the ideas of Ebenezer Howard which are now the municipalities of Greenbelt, Maryland, Greenhills, Ohio, and Greendale, Wisconsin.

- More than 20 cities in the San Francisco Bay Area have UGBs (see Greenbelt Alliance, a Bay Area organization that has been involved in establishing these boundaries).

- Staten Island Greenbelt and Brooklyn-Queens Greenway in New York City

- Barton Creek Greenbelt, Austin

- Ann Arbor, Michigan is acquiring conservation easements on agricultural land around the city without the establishment of an urban growth boundary. While the city's initial plan did not include the participation of surrounding townships, at least four townships have participated directly or have initiated their own efforts to protect agricultural land surrounding the city.

- Boise Greenbelt, Boise, Idaho

- The Jungle, Seattle

- The Emerald Necklace in Boston is halfway between a green belt and a greenway, nearly ringing central Boston. The final link in the chain, the Dorchesterway, was never constructed.