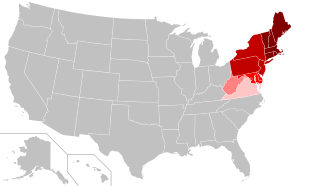

The states shown in the two darkest red shades are included in the United States Census Bureau Northeast Region. The Bureau subdivides the Northeast into:

New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania. States in lighter shades are included in other regional definitions.

The Northeastern United States, also referred to as the Northeast, is a geographical region of the United States bordered to the north by Canada, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the south by the southern United States, and to the west by the midwestern United States. The Northeast is one of the four regions defined by the United States Census Bureau for the collection and analysis of statistics.

The Census Bureau–defined region has a total area of 181,324 sq mi (469,630 km2) with 162,257 sq mi (420,240 km2) of that being land mass. Although it lacks a unified cultural identity, the Northeastern region is the nation's most economically developed, densely populated, and culturally diverse region.

Of the nation's four census regions, the Northeast has the

second-largest percentage of residents living in an urban setting, with

85 percent, and is home to the nation's largest metropolitan area. The Northeast is home to most of the Northeast megalopolis, the most economically significant and second most-populated of eleven megaregions within the United States, accounting for 20% of US GDP.

Composition

Geographically

there has always been some debate as to where the Northeastern United

States begins and ends. The vast area from central Virginia to northern Maine, and from western Pennsylvania (Pittsburgh) to the Atlantic Ocean, have all been loosely grouped into the Northeast at one time or another. Much of the debate has been what the cultural, economic, and urban aspects of the Northeast are, and where they begin or end as one reaches the borders of the region.

Using the Census Bureau's definition of the Northeast, the region includes nine states: they are Maine, New York, New Jersey, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania. The region is often subdivided into New England (the six states east of New York) and the Mid-Atlantic states

(New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania). This definition has been

essentially unchanged since 1880 and is widely used as a standard for

data tabulation. However, the Census Bureau has acknowledged the obvious limitations of this definition

and the potential merits of a proposal created after the 1950 census

that would include changing regional boundaries to include Delaware, Maryland, and the District of Columbia,

with the Mid-Atlantic states, but ultimately decided that "the new

system did not win enough overall acceptance among data users to warrant

adoption as an official new set of general-purpose State groupings. The

previous development of many series of statistics, arranged and issued

over long periods of time on the basis of the existing State groupings,

favored the retention of the summary units of the current regions and

divisions."

The Census Bureau confirmed in 1994 that it would continue to "review

the components of the regions and divisions to ensure that they continue

to represent the most useful combinations of States and State

equivalents."

Many organizations and reference works follow the Census Bureau's definition for the region; however, other entities define the Northeastern United States in significantly different ways for various purposes. The Association of American Geographers

divides the Northeast into two divisions: "New England", which consists

of Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and

Connecticut; and the "Middle States", which consists of New York,

Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. Similarly, the Geological Society of America defines the Northeast as these same states but with the addition of Maryland and the District of Columbia. The narrowest definitions include only the states of New England.

Other more restrictive definitions include New England and New York as

part of the Northeast United States, but exclude Pennsylvania and New

Jersey.

| City | City Population | Metro Population | U.S. Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| New York City | 8,398,748 | 19,979,477 | 1 |

| Philadelphia | 1,584,138 | 6,096,120 | 6 |

| Washington | 705,749 | 6,216,589 | 20 |

| Boston | 694,583 | 4,628,910 | 21 |

| Baltimore | 602,495 | 2,802,789 | 30 |

| Pittsburgh | 301,048 | 2,362,453 | 66 |

States beyond the Census Bureau definition are included in Northeast Region by various other entities:

- Various organizations include: Delaware, Maryland, and District of Columbia.

- The US EPA and NOAA include in their Northeast Region: Delaware, Maryland, and West Virginia.

- The National Fish and Wildlife Service includes in their Northeast Region: Delaware, Maryland, District of Columbia, West Virginia, and Virginia.

- The National Park Service includes in their Northeast Region: Delaware, Maryland, West Virginia, and Virginia (though small parts are also in the National Capital Region).

History

Indigenous peoples

Anthropologists recognize the "Northeastern Woodlands" as one of the cultural regions that existed in the Western Hemisphere at the time of European colonists in the 15th and later centuries. Most did not settle in North America until the 17th century. The cultural area, known as the "Northeastern Woodlands",

in addition to covering the entire Northeast U.S., also covered much of

what is now Canada and others regions of what is now the eastern United States. Among the many tribes that inhabited this area were those that made up the Iroquois nations and the numerous Algonquian peoples. In the United States of the 21st century, 18 federally recognized tribes reside in the Northeast.

For the most part, the people of the Northeastern Woodlands, on whose

lands European fishermen began camping to dry their codfish in the early

1600s, lived in villages, especially after being influenced by the

agricultural traditions of the Ohio and Mississippi valley societies.

Colonial history

All of the states making up the Northeastern region were among the original Thirteen Colonies, though Maine, Vermont, and Delaware were part of other colonies before the United States became independent in the American Revolution. The two cultural and geographic regions that form parts of the Northeastern region have distinct histories.

New England

The Landing of the Pilgrims, Henry A. Bacon (1877)

The first Europeans to settle New England were Pilgrims from England, who landed in present-day Massachusetts in 1620. The Pilgrims arrived on the ship Mayflower and founded Plymouth Colony so they could practice religion freely. Ten years later, a larger group of Puritans settled north of Plymouth Colony in Boston to form Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1636, colonists established Connecticut Colony and Providence Plantations. Providence was founded by Roger Williams,

who was banished by Massachusetts for his beliefs in freedom of

religion, and it was the first colony to guarantee all citizens freedom

of worship. Anne Hutchinson, who was also banished by Massachusetts, formed the town of Portsmouth. Providence, Portsmouth, and two other towns (Newport and Warwick) consolidated to form the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.

Although the first settlers of New England were motivated by

religion, in more recent history, New England has become one of the

least religious parts of the United States. In a 2009 Gallup

survey, less than half of residents in Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine,

and Massachusetts reported religion as an important part of their daily

life. In a 2010 Gallup survey, less than 30% of residents in Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, and Massachusetts reported attending church weekly, giving them the lowest church attendance among U.S. states.

New England played a prominent role in early American education.

Starting in the 17th century, the larger towns in New England opened grammar schools, the forerunner of the modern high school. The first public school in the English colonies was the Boston Latin School, founded in 1635. In 1636, the colonial legislature of Massachusetts founded Harvard College, the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States.

Mid-Atlantic

The first European explorer known to have explored the Atlantic shoreline of the Northeast since the Norse was Giovanni da Verrazzano in 1524. His ship La Dauphine explored the coast from what is now known as Florida to New Brunswick. Henry Hudson

explored the area of present-day New York in 1609 and claimed it for

the Netherlands. His journey stimulated Dutch interest, and the area

became known as New Netherland. In 1625, the city of New Amsterdam (the location of present-day New York City) was designated the capital of the province. The Dutch New Netherland settlement along the Hudson River and, for a time, the New Sweden settlement along the Delaware River divided the English settlements in the north and the south. In 1664, Charles II of England formally annexed New Netherland and incorporated it into the English colonial empire. The territory became the colonies of New York and New Jersey. New Jersey was originally split into East Jersey and West Jersey until the two were united as a royal colony in 1702.

In 1681, William Penn, who wanted to give Quakers a land of religious freedom, founded Pennsylvania and extended freedom of religion to all citizens.

Penn strongly desired access to the sea for his Pennsylvania Province and leased what then came to be known as the "Lower Counties on the Delaware" from the Duke.

Penn established representative government and briefly combined

his two possessions under one General Assembly in 1682. However, by 1704

the Province of Pennsylvania had grown so large that their

representatives wanted to make decisions without the assent of the Lower

Counties and the two groups of representatives began meeting on their

own, one at Philadelphia,

and the other at New Castle. Penn and his heirs remained proprietors of

both and always appointed the same person Governor for their Province

of Pennsylvania and their territory of the Lower Counties. The fact

that Delaware and Pennsylvania shared the same governor was not unique.

From 1703 to 1738, New York and New Jersey shared a governor. Massachusetts and New Hampshire also shared a governor for some time.

Environment

High Point Monument as seen from Lake Marcia at High Point, Sussex County, the highest elevation in New Jersey at 1,803 feet (550 m) above sea level

Cape Cod Bay, a leading tourist destination in Massachusetts

The Palisades along the Hudson River, New Jersey

U.S. Route 220 as it passes through Lamar Township, Pennsylvania

Topography

While most of the Northeastern United States lie in the Appalachian Highlands physiographic region, some are also part of the Atlantic coastal plain which extends south to the southern tip of Florida. The coastal plain areas (including Cape Cod in Massachusetts, Long Island in New York, most of New Jersey, Delaware, and the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland and Virginia) are generally low and flat, with sandy soil and marshy land. The highlands, including the Piedmont and the Appalachian Mountains,

are generally heavily forested, ranging from rolling hills to summits

greater than 6,000 feet (1,800 m), and pocked with many lakes. The highest peak in the Northeast is Mount Washington (New Hampshire), at 6,288 feet (1,917 m).

Land use

As of 2007,

forest-use covered approximately 60% of the Northeastern states

(including Delaware, Maryland, and the District of Columbia), about

twice the national average. About 12% was cropland and another 4%

grassland pasture or range. There is also more urbanized land in the

Northeast (11%) than any other region in the U.S.

Climate

The climate of the Northeastern United States varies from northernmost Maine to southernmost Maryland.

The climate of the region is created by the position of the general

west to east flow of weather in the middle latitudes that much of the

USA is controlled by and the position and movement of the subtropical

highs. Summers are normally warm in northern areas to hot in southern

areas. In summer, the building Bermuda High

pumps warm and sultry air toward the Northeast, and frequent (but

brief) thundershowers are common on hot summer days. In winter the

subtropical high retreats southeastward, and the polar jet stream moves

south bringing colder air masses from up in Canada and more frequent

storm systems to the region. Winter often brings both rain and snow as

well as surges of both warm and cold air.

The basic climate of the Northeast can be divided into a colder

and snowier interior (Pennsylvania, New York State, and New England),

and a milder coast and coastal plain from southern Rhode Island southward, including, New Haven, CT, New York City, Philadelphia, Trenton, Wilmington, Baltimore...etc.).

Annual mean temperatures range from the low 50s F from Maryland to

southern Connecticut, to the 40s F in most of New York State, New

England, and northern Pennsylvania.

Wildlife

The Northeast has 72 National Wildlife Refuges, encompassing more than 500,000 acres (780 sq mi; 2,000 km2) of habitat, and designed to protect some of the 92 different threatened and endangered species living in the region.

Demographics

New York City, the most populous city in the Northeast and all of the United States

Philadelphia, the second most populous city in the Northeast and the sixth most populated city in the United States

Washington, D.C., the third most populous city in the Northeast and the capital of the United States

Boston, the most populated city in Massachusetts and New England and the fourth most populated city in the Northeast

As of the July 2013 U.S. Census Bureau estimate, the population of the region totaled 55,943,073. With an average of 345.5 people per square mile, the Northeast is 2.5

times as densely populated as the second-most dense region, the South. Since the last century, the U.S. population has been shifting away from the Northeast (and Midwest) toward the South and West.

The two U.S. Census Bureau divisions in the Northeast (New England and Mid-Atlantic) rank #2 and #1 among the 9 divisions in population density according to the 2013 population estimate. The South Atlantic region (233.1) was very close behind New England (233.2). Due to the faster growth of the South Atlantic

region, it will take over the #2 division rank in population density in

the next estimate, dropping New England to 3rd position. New England is

projected to retain the number 3 rank for many, many years, as the only

other lower-ranked division with even half the population density of

New England is the East North Central division (192.1) and this region's population is projected to grow slowly.

| State | 2017 Estimate | 2010 Census | Change | Area | Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | 3,588,184 | 3,574,097 | +0.39% | 4,842.35 sq mi (12,541.6 km2) | 741/sq mi (286/km2) |

| Maine | 1,335,907 | 1,328,361 | +0.57% | 30,842.90 sq mi (79,882.7 km2) | 43/sq mi (17/km2) |

| Massachusetts | 6,859,819 | 6,547,629 | +4.77% | 7,800.05 sq mi (20,202.0 km2) | 879/sq mi (340/km2) |

| New Hampshire | 1,342,795 | 1,316,470 | +2.00% | 8,952.64 sq mi (23,187.2 km2) | 150/sq mi (58/km2) |

| Rhode Island | 1,059,639 | 1,052,567 | +0.67% | 1,033.81 sq mi (2,677.6 km2) | 1,025/sq mi (396/km2) |

| Vermont | 623,657 | 625,741 | −0.33% | 9,216.65 sq mi (23,871.0 km2) | 68/sq mi (26/km2) |

| New England | 14,810,001 | 14,444,865 | +2.53% | 62,688.4 sq mi (162,362 km2) | 236/sq mi (91/km2) |

| New Jersey | 9,005,644 | 8,791,894 | +2.43% | 7,354.21 sq mi (19,047.3 km2) | 1,225/sq mi (473/km2) |

| New York | 19,849,399 | 19,378,102 | +2.43% | 47,126.36 sq mi (122,056.7 km2) | 421/sq mi (163/km2) |

| Pennsylvania | 12,805,537 | 12,702,379 | +0.81% | 44,742.67 sq mi (115,883.0 km2) | 286/sq mi (111/km2) |

| Middle Atlantic | 41,660,580 | 40,872,375 | +1.93% | 99,223.24 sq mi (256,987.0 km2) | 420/sq mi (162/km2) |

| Total | 56,470,581 | 55,317,240 | +2.08% | 161,911.64 sq mi (419,349.2 km2) | 349/sq mi (135/km2) |

| Delaware | 961,939 | 897,936 | +7.13% | 1,948.54 sq mi (5,046.7 km2) | 494/sq mi (191/km2) |

| Maryland | 6,052,177 | 5,773,785 | +4.82% | 9,707.24 sq mi (25,141.6 km2) | 623/sq mi (241/km2) |

| District of Columbia | 693,972 | 601,767 | +15.32% | 61.05 sq mi (158.1 km2) | 11,367/sq mi (4,389/km2) |

| Total (Census + DE/MD/DC) | 64,178,669 | 62,590,728 | +2.54% | 173,628.47 sq mi (449,695.7 km2) | 370/sq mi (143/km2) |

Economy

As of 2012, the Northeast accounts for approximately 23% of U.S. gross domestic product.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission oversees 34 nuclear reactors, eight for research or testing and 26 for power production in the Northeastern United States.

New York City, considered a global financial center, is in the Northeast.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons maintains 17 federal prisons and two affiliated private facilities in the region.

Transportation

The following table includes all eight airports categorized by the FAA as large hubs located in the Northeastern states (New England and Eastern regions):

| Rank | Metro area served | Airport code |

Airport name | Largest airline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | New York | JFK | John F Kennedy International | JetBlue (37%) |

| 2 | New York | EWR | Newark Liberty International | United (49%) |

| 3 | Philadelphia | PHL | Philadelphia International | American (80%) |

| 4 | Boston | BOS | General Edward Lawrence Logan International | JetBlue (29%) |

| 5 | New York | LGA | La Guardia | Delta (21%) |

| 6 | Baltimore/Washington | BWI | Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall | Southwest (65%) |

| 7 | Washington | IAD | Washington Dulles International | United (41%) |

| 8 | Washington | DCA | Ronald Reagan Washington National | American (50%) |

Culture

One geographer, Wilbur Zelinsky, asserts that the Northeast region lacks a unified cultural identity, but has served as a "culture hearth" for the rest of the nation. Several much smaller geographical regions within the Northeast have distinct cultural identities.

Landmarks

Almost half of the National Historic Landmarks maintained by the National Park Service are located in the Northeastern United States.

Religion

According to a 2009 Gallup poll,

the Northeastern states differ from most of the rest of the U.S. in

religious affiliation, generally reflecting the descendants of

immigration patterns of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with

many Catholics arriving from Ireland, Italy, Canada, and eastern Europe.

Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, and New Jersey are the only

states in the nation where Catholics outnumber Protestants and other Christian denominations. More than 20% of respondents in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont declared no religious identity.

Compared to other U.S. regions, the Northeast, along with the Pacific

Northwest, has the lowest regular religious service attendance and the

fewest people for whom religion is an important part of their daily

lives.

Sports

The Northeast region is home to numerous professional sports franchises in the "Big Four" leagues (NFL, NBA, NHL, and MLB), with more than 100 championships collectively among them.

- New York metropolitan area: Giants, Jets (NFL), Yankees, Mets (MLB), Knicks, Nets (NBA), Rangers, Islanders, Devils (NHL)

- Philadelphia: Eagles (NFL), Phillies (MLB), 76ers (NBA), Flyers (NHL)

- Boston: Patriots (NFL), Red Sox (MLB), Celtics (NBA), Bruins (NHL)

- Pittsburgh: Steelers (NFL), Pirates (MLB), Penguins (NHL)

- Buffalo: Bills (NFL), Sabres (NHL)

Major League Soccer features five Northeastern teams: D.C. United, New England Revolution, New York City FC, New York Red Bulls, and Philadelphia Union. The region also has three WNBA teams: Connecticut Sun, New York Liberty, and Washington Mystics.

Notable golf tournaments in the Northeastern United States include the Deutsche Bank Championship, The Barclays, Quicken Loans National, and Atlantic City LPGA Classic. The US Open, held at New York City, is one of the four Grand Slam tennis tournaments, whereas the Washington Open is part of the ATP World Tour 500 series.

Notable Northeastern motorsports tracks include Watkins Glen International, Dover International Speedway, Pocono Raceway, New Hampshire Motor Speedway, and Lime Rock Park, which have hosted Formula One, IndyCar, NASCAR, and International Motor Sports Association races. Also, drag strips such as Englishtown, Epping, and Reading have hosted NHRA national events. Pimlico Race Course at Baltimore and Belmont Park at New York host the Preakness Stakes and Belmont Stakes horse races, which are part of the Triple Crown of Thoroughbred Racing.

The region has also been noted for the prevalence of the traditionally Northeastern sports of ice hockey and lacrosse.

Health

The rate

of potentially preventable hospitalizations in the Northeastern United

States fell from 2005 to 2011 for overall conditions, acute conditions,

and chronic conditions.

Politics

The Northeastern United States tended to vote Republican in federal elections through the first half of the 20th century, but the region has since the 1990s shifted to become the most Democratic in the nation. Results from a 2008 Gallup poll

indicated that eight of the top ten Democratic states were located in

the region, with every Northeastern state having a Democratic party

affiliation advantage of at least ten points. The following table demonstrates Democratic support in the Northeast as compared to the remainder of the nation.

| Year | % President vote | % Senate seats | % House seats | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast | Remainder | Northeast | Remainder | Northeast | Remainder | |

| 2000 | 57.6 | 47.5 | 60.0 | 46.3 | 59.6 | 45.7 |

| 2002 | 60.0 | 45.0 | 58.3 | 44.7 | ||

| 2004 | 57.1 | 47.3 | 60.0 | 40.0 | 59.5 | 43.0 |

| 2006 | 75.0 | 45.0 | 73.8 | 48.3 | ||

| 2008 | 60.7 | 52.0 | 80.0 | 52.5 | 81.0 | 52.9 |

| 2010 | 75.0 | 47.5 | 67.9 | 38.5 | ||