A political party is an organized group of people who have the same ideology, or who otherwise have the same political positions, and who field candidates for elections, in an attempt to get them elected and thereby implement the party's agenda. They are a defining element of representative democracy.

While there is some international commonality in the way political parties are recognized and in how they operate, there are often many differences, and some are significant. Most of political parties have an ideological core, but some do not, and many represent ideologies very different from their ideology at the time the party was founded. Many countries, such as Germany and India, have several significant political parties, and some nations have one-party systems, such as China and Cuba. The United States is in practice a two-party system but with many smaller parties also participating.

Historical development

The idea of people forming large groups or factions to advocate for their shared interests is ancient. Plato mentions the political factions of Classical Athens in the Republic, and Aristotle discusses the tendency of different types of government to produce factions in the Politics. Certain ancient disputes were also factional, like the Nika riots between two chariot racing factions at the Hippodrome of Constantinople.

However, modern political parties are considered to have emerged around

the end of the 18th or early 19th centuries, appearing first in Europe

and the United States. What distinguishes political parties from factions and interest groups is that political parties use an explicit label to identify their members as having shared electoral and legislative goals.

The transformation from loose factions into organised modern political

parties is considered to have first occurred in either the United Kingdom or the United States, with the United Kingdom's Conservative Party and the Democratic Party of the United States both frequently called the world's "oldest continuous political party".

Emergence in Britain

The party system that emerged in early modern Britain is considered to be one of the world's first, with origins in the factions that emerged from the Exclusion Crisis and Glorious Revolution of the late 17th century. The Whig faction originally organised itself around support for Protestant constitutional monarchy as opposed to absolute rule, whereas the conservative Tory faction (originally the Royalist or Cavalier faction of the English Civil War) supported a strong monarchy. These two groups structured disputes in the politics of the United Kingdom

throughout the 18th century. Throughout the next several centuries,

these loose factions began to adopt more coherent political tendencies

and ideologies: the liberal political ideas of John Locke and the notion of universal rights espoused by theorists like Algernon Sidney and later John Stuart Mill were major influences on the Whigs, whereas the Tories eventually came to be identified with conservative philosophers like Edmund Burke.

The period between the advent of factionalism, around the Glorious Revolution, and the accession of George III in 1760 was characterised by Whig supremacy, during which the Whigs remained the most powerful bloc and consistently championed constitutional monarchy with strict limits on the monarch's power, opposed the accession of a Catholic king, and believed in extending toleration to nonconformist Protestants and dissenters. Although the Tories were out of office for half a century, they largely remained a united opposition to the Whigs.

When they lost power, the old Whig leadership dissolved into a decade of factional chaos with distinct Grenvillite, Bedfordite, Rockinghamite, and Chathamite

factions successively in power, and all referring to themselves as

"Whigs". The first distinctive political parties emerged from this

chaos. The first such party was the Rockingham Whigs under the leadership of Charles Watson-Wentworth and the intellectual guidance of the political philosopher Edmund Burke.

Burke laid out a philosophy that described the basic framework of the

political party as "a body of men united for promoting by their joint

endeavours the national interest, upon some particular principle in

which they are all agreed".

As opposed to the instability of the earlier factions, which were often

tied to a particular leader and could disintegrate if removed from

power, the party was centred around a set of core principles and

remained out of power as a united opposition to government.

In A Block for the Wigs (1783), James Gillray caricatured Fox's return to power in a coalition with North. George III is the blockhead in the centre.

A coalition including the Rockingham Whigs, led by the Earl of Shelburne, took power in 1782, only to collapse after Rockingham's death. The new government, led by the radical politician Charles James Fox in coalition with Lord North, was soon brought down and replaced by William Pitt the Younger

in 1783. It was now that a genuine two-party system began to emerge,

with Pitt leading the new Tories against a reconstituted "Whig" party

led by Fox. The modern Conservative Party was created out of these Pittite Tories. In 1859 under Lord Palmerston, the Whigs, heavily influenced by the classical liberal ideas of Adam Smith, joined together with the free trade Tory followers of Robert Peel and the independent Radicals to form the Liberal Party.

Emergence in the United States

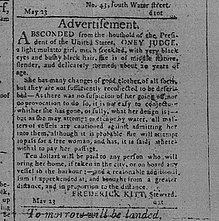

Although the framers of the 1787 United States Constitution

did not anticipate that American political disputes would be primarily

organised around political parties, political controversies in the early

1790s over the extent of federal government powers saw the emergence of two proto-political parties: the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party, which were championed by Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, respectively. However, a consensus reached on these issues ended party politics in 1816 for nearly a decade, a period commonly known as the Era of Good Feelings.

The splintering of the Democratic-Republican Party in the aftermath of the contentious 1824 presidential election

led to the re-emergence of political parties. Two major parties would

dominate the political landscape for the next quarter-century: the

Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, established by Henry Clay from the National Republicans

and from other Anti-Jackson groups. When the Whig Party fell apart in

the mid-1850s, its position as a major U.S. political party was filled

by the Republican Party.

Worldwide spread

Charles Stewart Parnell, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party

Another candidate for the first modern party system to emerge is that of Sweden. Throughout the second half of the 19th century, the party model of politics was adopted across Europe. In Germany, France, Austria and elsewhere, the 1848 Revolutions

sparked a wave of liberal sentiment and the formation of representative

bodies and political parties. The end of the century saw the formation

of large socialist parties in Europe, some conforming to the philosophy of Karl Marx, others adapting social democracy through the use of reformist and gradualist methods.

At the same time, the Home Rule League Party, campaigning for Home Rule for Ireland in the British Parliament, was fundamentally changed by the Irish political leader Charles Stewart Parnell in the 1880s. In 1882, he changed his party's name to the Irish Parliamentary Party and created a well-organized grassroots structure, introducing membership to replace ad hoc

informal groupings. He created a new selection procedure to ensure the

professional selection of party candidates committed to taking their

seats, and in 1884 he imposed a firm 'party pledge' which obliged MPs to

vote as a bloc in parliament on all occasions. The creation of a strict

party whip and a formal party structure was unique at the time, preceded only by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (1875), even though the latter was persecuted by Otto von Bismarck

from 1878 to 1890. These parties' efficient structure and control

contrasted with the loose rules and flexible informality found in the main British parties, and represented the development of new forms of party organisation, which constituted a "model" in the 20th-century.

Origin of political parties

Political

parties are a nearly ubiquitous feature of modern countries. Nearly all

democratic countries have strong political parties, and many political

scientists consider countries with fewer than two parties to necessarily

be autocratic.

However, these sources allow that a country with multiple competitive

parties is not necessarily democratic, and the politics of many

autocratic countries are organised around one dominant political party. There are many explanations for how and why political parties are such a crucial part of modern states.

Social cleavages

One of the core explanations for why political parties exist is that

they arise from existing divisions among people. Building on Harold Hotelling's work on the aggregation of preferences and Duncan Black's development of social choice theory, Anthony Downs

showed how an underlying distribution of preferences in an electorate

can produce regular results in the aggregate, such as the median voter theorem.

This abstract model shows that parties can arise from variations within

an electorate, and can adjust themselves to the patterns in the

electorate. However, Downs assumed that some distribution of preferences

exists, rather than attributing any meaning to that distribution.

Seymour Martin Lipset and Stein Rokkan

made the idea of differences within an electorate more concrete by

arguing that several major party systems of the 1960s were the result of

social cleavages that had already existed in the 1920s.

They identify four lasting cleavages in the countries they examine: a

Center-Periphery cleavage regarding religion and language, a

State-Church cleavage centered on control of mass education, a

Land-Industry cleavage regarding freedom of industry and agricultural

policies, and an Owner-Worker cleavage which includes a conflict between

nationalism and internationalism.

Subsequent authors have expanded on or modified these cleavages,

particularly when examining parties in other parts of the world.

The argument that parties are produced by social cleavages has

drawn several criticisms. Some authors have challenged the theory on

empirical grounds, either finding no evidence for the claim that parties

emerge from existing cleavages or arguing that this claim is not

empirically testable.

Others note that while social cleavages might cause political parties

to exist, this obscures the opposite effect: that political parties also

cause changes in the underlying social cleavages.

A further objection is that, if the explanation for where parties come

from is that they emerge from existing social cleavages, then the theory

has not identified what causes parties unless it also explains where

social cleavages come from; one response to this objection, along the

lines of Charles Tilly's bellicist theory of state-building, is that social cleavages are formed by historical conflicts.

Individual and group incentives

An alternative explanation for why parties are ubiquitous across the world is that the formation of parties provides compatible incentives for candidates and legislators. One explanation for the existence of parties, advanced by John Aldrich,

is that the existence of political parties means that a candidate in

one electoral district has an incentive to assist a candidate in a

different district, when those two candidates have a similar ideology.

One reason that this incentive exists is that parties can solve

certain legislative challenges that a legislature of unaffiliated

members might face. Gary W. Cox and Mathew D. McCubbins

argue that the development of many institutions can be explained by

their power to constrain the incentives of individuals; a powerful

institution can prohibit individuals from acting in ways that harm the

community.

This suggests that political parties might be mechanisms for preventing

candidates with similar ideologies from acting to each other's

detriment.

One specific advantage that candidates might obtain from helping

similar candidates in other districts is that the existence of a party

apparatus can help coalitions of electors to agree on ideal policy

choices, which is in general not possible.

This could be true even in contexts where it is only slightly

beneficial to be part of a party; models of how individuals coordinate

on joining a group or participating in an event show how even a weak

preference to be part of a group can provoke mass participation.

Parties as heuristics

Parties may be necessary for many individuals to participate in

politics, because they provide a massively simplifying heuristic which

allows people to make informed choices with a much lower cognitive cost.

Without political parties, electors would have to evaluate every

individual candidate in every single election they are eligible to vote

in. Instead, parties enable electors to make judgments about a few

groups instead of a much larger number of individuals. Angus Campbell, Philip Converse, Warren Miller, and Donald E. Stokes argued in The American Voter that identification with a political party is a crucial determinant of whether and how an individual will vote.

Because it is much easier to become informed about a few parties'

platforms than about many candidates' personal positions, parties reduce

the cognitive burden for people to cast informed votes. However,

evidence suggests that over the last several decades the strength of

party identification has been weakening, so this may be a less important

function for parties to provide than it was in the past.

Structure

A political party is typically led by a party leader (the most powerful member and spokesperson representing the party), a party secretary (who maintains the daily work and records of party meetings), party treasurer (who is responsible for membership dues) and party chair

(who forms strategies for recruiting and retaining party members, and

also chairs party meetings). Most of the above positions are also

members of the party executive, the leading organization which sets

policy for the entire party at the national level. The structure is far

more decentralized in the United States because of the separation of

powers, federalism and the multiplicity of economic interests and

religious sects. Even state parties are decentralized as county and

other local committees are largely independent of state central

committees. The national party leader in the U.S. will be the president,

if the party holds that office, or a prominent member of Congress in

opposition (although a big-state governor may aspire to that role).

Officially, each party has a chairman for its national committee who is a

prominent spokesman, organizer and fund-raiser, but without the status

of prominent elected office holders.

In parliamentary democracies, on a regular, periodic basis, party conferences

are held to elect party officers, although snap leadership elections

can be called if enough members opt for such. Party conferences are also

held in order to affirm party values for members in the coming year.

American parties also meet regularly and, again, are more subordinate to

elected political leaders.

Depending on the demographic spread of the party membership,

party members form local or regional party committees in order to help

candidates run for local or regional offices in government. These local

party branches reflect the officer positions at the national level.

It is also customary for political party members to form wings

for current or prospective party members, most of which fall into the

following two categories:

- identity-based: including youth wings and/or armed wings

- position-based: including wings for candidates, mayors, governors, professionals, students, etc. The formation of these wings may have become routine but their existence is more of an indication of differences of opinion, intra-party rivalry, the influence of interest groups, or attempts to wield influence for one's state or region.

These are useful for party outreach, training and employment. Many

young aspiring politicians seek these roles and jobs as stepping stones

to their political careers in legislative or executive offices.

The internal structure of political parties has to be democratic

in some countries. In Germany Art. 21 Abs. 1 Satz 3 GG establishes a

command of inner-party democracy.

Parliamentary parties

When

the party is represented by members in the lower house of parliament,

the party leader simultaneously serves as the leader of the parliamentary group of that full party representation; depending on a minimum number of seats held, Westminster-based parties typically allow for leaders to form frontbench

teams of senior fellow members of the parliamentary group to serve as

critics of aspects of government policy. When a party becomes the

largest party not part of the Government, the party's parliamentary

group forms the Official Opposition, with Official Opposition frontbench team members often forming the Official Opposition Shadow cabinet.

When a party achieves enough seats in an election to form a majority,

the party's frontbench becomes the Cabinet of government ministers. They

are all elected members. There are members who attend party without

promotion.

Regulation

The

freedom to form, declare membership in, or campaign for candidates from

a political party is considered a measurement of a state's adherence to

liberal democracy as a political value. Regulation of parties may run

from a crackdown on or repression of all opposition parties, a norm for

authoritarian governments, to the repression of certain parties which

hold or promote ideals which run counter to the general ideology of the

state's incumbents (or possess membership by-laws which are legally

unenforceable).

Furthermore, in the case of far-right, far-left and regionalism

parties in the national parliaments of much of the European Union,

mainstream political parties may form an informal cordon sanitaire which applies a policy of non-cooperation towards those "Outsider Parties" present in the legislature which are viewed as 'anti-system' or otherwise unacceptable for government. Cordons sanitaire,

however, have been increasingly abandoned over the past two decades in

multi-party democracies as the pressure to construct broad coalitions in

order to win elections – along with the increased willingness of

outsider parties themselves to participate in government – has led to

many such parties entering electoral and government coalitions.

Starting in the second half of the 20th century, modern

democracies have introduced rules for the flow of funds through party

coffers, e.g. the Canada Election Act 1976, the PPRA in the U.K. or the

FECA in the U.S. Such political finance

regimes stipulate a variety of regulations for the transparency of

fundraising and expenditure, limit or ban specific kinds of activity and

provide public subsidies for party activity, including campaigning.

Partisan style

Partisan

style varies according to each jurisdiction, depending on how many

parties there are, and how much influence each individual party has.

Nonpartisan systems

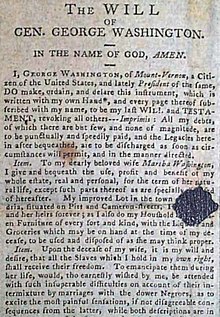

In a nonpartisan system, no official political parties exist, sometimes reflecting legal restrictions on political parties.

In nonpartisan elections, each candidate is eligible for office on his

or her own merits. In nonpartisan legislatures, there are no typically

formal party alignments within the legislature. The administration of George Washington and the first few sessions of the United States Congress were nonpartisan. Washington also warned against political parties during his Farewell Address. In the United States, the unicameral legislature of Nebraska is nonpartisan but is elected and often votes on informal party lines. In Canada, the territorial legislatures of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut are nonpartisan. In New Zealand, Tokelau

has a nonpartisan parliament. Many city and county governments in the

United States and Canada are nonpartisan. Nonpartisan elections and

modes of governance are common outside of state institutions.

Unless there are legal prohibitions against political parties, factions

within nonpartisan systems often evolve into political parties.

Uni-party systems

In one-party systems,

one political party is legally allowed to hold effective power.

Although minor parties may sometimes be allowed, they are legally

required to accept the leadership of the dominant party. This party may

not always be identical to the government, although sometimes positions

within the party may in fact be more important than positions within the

government. North Korea and China are examples; others can be found in Fascist states, such as Nazi Germany between 1934 and 1945. The one-party system is thus often equated with dictatorships and tyranny.

In dominant-party systems,

opposition parties are allowed, and there may be even a deeply

established democratic tradition, but other parties are widely

considered to have no real chance of gaining power. Sometimes,

political, social and economic circumstances, and public opinion are the

reason for others parties' failure. Sometimes, typically in countries

with less of an established democratic tradition, it is possible the

dominant party will remain in power by using patronage and sometimes by voting fraud.

In the latter case, the definition between dominant and one-party

system becomes rather blurred. Examples of dominant party systems

include the People's Action Party in Singapore, the African National Congress in South Africa, the Cambodian People's Party in Cambodia, the Liberal Democratic Party in Japan, and the National Liberation Front in Algeria. One-party dominant system also existed in Mexico with the Institutional Revolutionary Party until the 1990s, in the southern United States with the Democratic Party from the late 19th century until the 1970s, in Indonesia with the Golkar from the early 1970s until 1998.

Bi-party systems

Two-party systems are states such as Honduras, Jamaica, Malta, Ghana

and the United States in which there are two political parties dominant

to such an extent that electoral success under the banner of any other

party is almost impossible. One right wing coalition party and one left

wing coalition party is the most common ideological breakdown in such a

system but in two-party states political parties are traditionally catch all parties which are ideologically broad and inclusive.

The United States has gone through several party systems,

each of which has been essentially two-party in nature. The divide has

typically been between a conservative and liberal party; presently, the Republican Party and Democratic Party

serve these roles. Third parties have seen extremely little electoral

success, and successful third party runs typically lead to vote splitting

due to the first-past-the-post, winner-takes-all systems used in most

US elections. There have been several examples of third parties

siphoning votes from major parties, such as Theodore Roosevelt in 1912 and George Wallace in 1968, resulting in the victory of the opposing major party. In presidential elections, the Electoral College system has prevented third party candidates from being competitive, even when they have significant support (such as in 1992).

More generally, parties with a broad base of support across regions or

among economic and other interest groups have a greater chance of

winning the necessary plurality in the U.S.'s largely single-member

district, winner-take-all elections.

The UK political system, while technically a multi-party system,

has functioned generally as a two-party (sometimes called a

"two-and-a-half party") system; since the 1920s the two largest

political parties have been the Conservative Party and the Labour Party. Before the Labour Party rose in British politics the Liberal Party was the other major political party along with the Conservatives. Though coalition and minority governments have been an occasional feature of parliamentary politics, the first-past-the-post electoral system used for general elections

tends to maintain the dominance of these two parties, though each has

in the past century relied upon a third party to deliver a working

majority in Parliament. (A plurality voting system usually leads to a two-party system, a relationship described by Maurice Duverger and known as Duverger's Law.) There are also numerous other parties that hold or have held a number of seats in Parliament.

Multi-party systems

A poster for the European Parliament election 2004 in Italy, showing party lists

Multi-party systems are systems in which more than two parties are represented and elected to public office.

Australia, Canada, Nepal,

Pakistan, India, Ireland, United Kingdom and Norway are examples of

countries with two strong parties and additional smaller parties that

have also obtained representation. The smaller or "third" parties may

hold the balance of power in a parliamentary system, and thus may be invited to form a part of a coalition government together with one of the larger parties, or may provide a supply and confidence agreement to the government; or may instead act independently from the dominant parties.

More commonly, in cases where there are three or more parties, no

one party is likely to gain power alone, and parties have to work with

each other to form coalition governments. This is almost always the case

in Germany on national and state level, and in most constituencies at

the communal level. Furthermore, since the forming of the Republic of Iceland there has never been a government not led by a coalition, usually involving the Independence Party or the Progressive Party. A similar situation exists in the Republic of Ireland,

where no one party has held power on its own since 1989. Since then,

numerous coalition governments have been formed. These coalitions have

been led exclusively by either Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael.

Political change is often easier with a coalition government than in one-party or two-party dominant systems.

If factions in a two-party system are in fundamental disagreement on

policy goals, or even principles, they can be slow to make policy

changes, which appears to be the case now in the U.S. with power split

between Democrats and Republicans. Still coalition governments struggle,

sometimes for years, to change policy and often fail altogether, post

World War II France and Italy being prime examples. When one party in a

two-party system controls all elective branches, however, policy changes

can be both swift and significant. Democrats Woodrow Wilson, Franklin

Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson were beneficiaries of such fortuitous

circumstances, as were Republicans as far removed in time as Abraham

Lincoln and Ronald Reagan. Barack Obama briefly had such an advantage

between 2009 and 2011.

Funding

Political parties are funded by contributions from

- party members and other individuals,

- organizations, which share their political ideas (e.g. trade union affiliation fees) or which could benefit from their activities (e.g. corporate donations) or

- governmental or public funding.

Political parties, still called factions by some, especially those in the governmental apparatus, are lobbied vigorously by organizations, businesses and special interest groups such as trade unions.

Money and gifts-in-kind to a party, or its leading members, may be

offered as incentives. Such donations are the traditional source of

funding for all right-of-centre cadre parties. Starting in the late 19th

century these parties were opposed by the newly founded left-of-centre

workers' parties. They started a new party type, the mass membership

party, and a new source of political fundraising, membership dues.

From the second half of the 20th century on parties which

continued to rely on donations or membership subscriptions ran into

mounting problems. Along with the increased scrutiny of donations there

has been a long-term decline in party memberships in most western

democracies which itself places more strains on funding. For example, in

the United Kingdom and Australia membership of the two main parties in

2006 is less than an 1/8 of what it was in 1950, despite significant

increases in population over that period.

In some parties, such as the post-communist parties of France and Italy or the Sinn Féin party and the Socialist Party,

elected representatives (i.e. incumbents) take only the average

industrial wage from their salary as a representative, while the rest

goes into party coffers. Although these examples may be rare nowadays, "rent-seeking" continues to be a feature of many political parties around the world.

In the United Kingdom, it has been alleged that peerages have been awarded to contributors to party funds, the benefactors becoming members of the House of Lords and thus being in a position to participate in legislating. Famously, Lloyd George was found to have been selling peerages. To prevent such corruption in the future, Parliament passed the Honours (Prevention of Abuses) Act 1925 into law. Thus the outright sale of peerages and similar honours became a criminal act.

However, some benefactors are alleged to have attempted to circumvent

this by cloaking their contributions as loans, giving rise to the 'Cash for Peerages' scandal.

Such activities as well as assumed "influence peddling"

have given rise to demands that the scale of donations should be

capped. As the costs of electioneering escalate, so the demands made on

party funds increase. In the UK some politicians are advocating that

parties should be funded by the state;

a proposition that promises to give rise to interesting debate in a

country that was the first to regulate campaign expenses (in 1883).

In many other democracies such subsidies for party activity (in

general or just for campaign purposes) have been introduced decades ago.

Public financing for parties and/ or candidates (during election times

and beyond) has several permutations and is increasingly common.

Germany, Sweden, Israel, Canada, Australia, Austria and Spain are cases

in point. More recently among others France, Japan, Mexico, the

Netherlands and Poland have followed suit.

There are two broad categories of public funding, direct, which

entails a monetary transfer to a party, and indirect, which includes

broadcasting time on state media, use of the mail service or supplies. According to the Comparative Data from the ACE Electoral Knowledge Network,

out of a sample of over 180 nations, 25% of nations provide no direct

or indirect public funding, 58% provide direct public funding and 60% of

nations provide indirect public funding.

Some countries provide both direct and indirect public funding to

political parties. Funding may be equal for all parties or depend on

the results of previous elections or the number of candidates

participating in an election. Frequently parties rely on a mix of private and public funding and are required to disclose their finances to the Election management body.

In fledgling democracies funding can also be provided by foreign aid. International donors provide financing to political parties in developing countries as a means to promote democracy and good governance.

Support can be purely financial or otherwise. Frequently it is provided

as capacity development activities including the development of party

manifestos, party constitutions and campaigning skills. Developing links between ideologically linked parties is another common feature of international support for a party.

Sometimes this can be perceived as directly supporting the political

aims of a political party, such as the support of the US government to

the Georgian party behind the Rose Revolution.

Other donors work on a more neutral basis, where multiple donors

provide grants in countries accessible by all parties for various aims

defined by the recipients.

There have been calls by leading development think-tanks, such as the

Overseas Development Institute, to increase support to political parties

as part of developing the capacity to deal with the demands of

interest-driven donors to improve governance.

Colors and emblems

Generally speaking, over the world, political parties associate themselves with colors, primarily for identification, especially for voter recognition during elections.

- Blue generally denotes conservatism.

- Yellow is often used for liberalism or libertarianism.

- Red often signifies social democratic, socialist, or communist parties.

- Green is often associated with green politics, Islamism, agrarianism, or Irish republicanism.

- Orange is the traditional color of Christian democracy.

- Black is generally associated with fascist parties, going back to Benito Mussolini's blackshirts, but also with Anarchism. Similarly, brown is sometimes associated with Nazism, going back to the Nazi Party's tan-uniformed Stormtroopers.

Color associations are useful when it is not desirable to make rigorous links to parties, particularly when coalitions and alliances are formed between political parties and other organizations, for example: "Purple" (Red-Blue) alliances, Red-green alliances, Blue-green alliances, Traffic light coalitions, Pan-green coalitions, and Pan-blue coalitions.

Political color schemes in the United States diverge from

international norms. Since 2000, red has become associated with the

right-wing Republican Party and blue with the left-wing Democratic Party.

However, unlike political color schemes of other countries, the parties

did not choose those colors; they were used in news coverage of the

2000 election results and ensuing legal battle and caught on in popular

usage. Prior to the 2000 election the media typically alternated which

color represented which party each presidential election cycle. The

color scheme happened to get inordinate attention that year, so the

cycle was stopped lest it cause confusion the following election.

Emblems

The emblem of socialist parties is often a red rose held in a fist. Communist parties often use a hammer to represent the worker, a sickle to represent the farmer, or both a hammer and a sickle to refer to both at the same time.

The emblem of Nazism, the swastika or "hakenkreuz",

has been adopted as a near-universal symbol for almost any organised

white supremacist group, even though it dates from more ancient times.

International organization

During

the 19th and 20th century, many national political parties organized

themselves into international organizations along similar policy lines.

Notable examples are The Universal Party, International Workingmen's Association (also called the First International), the Socialist International (also called the Second International), the Communist International (also called the Third International), and the Fourth International, as organizations of working class parties, or the Liberal International (yellow), Hizb ut-Tahrir, Christian Democratic International and the International Democrat Union (blue). Organized in Italy in 1945, the International Communist Party, since 1974 headquartered in Florence has sections in six countries. Worldwide green parties have recently established the Global Greens. The Universal Party, The Socialist International, the Liberal International, and the International Democrat Union

are all based in London.

Some administrations (e.g. Hong Kong) outlaw formal linkages between

local and foreign political organizations, effectively outlawing

international political parties.

Types

Klaus von Beyme

categorised European parties into nine families, which described most

parties. He was able to arrange seven of them from left to right:

Communist, Socialist, Green, Liberal, Christian democratic, Conservative and Libertarian. The position of two other types, Agrarian and Regional/Ethnic parties varied.

Political scientists have distinguished between different types

of political parties that have evolved throughout history. These include

cadre parties, mass parties, catch-all parties and cartel parties.

Cadre parties were political elites that were concerned with contesting

elections and restricted the influence of outsiders, who were only

required to assist in election campaigns. Mass parties tried to recruit

new members who were a source of party income and were often expected to

spread party ideology as well as assist in elections. In the United

States, where both major parties were cadre parties, the introduction of

primaries and other reforms has transformed them so that power is held

by activists who compete over influence and nomination of candidates.

Cadre party

A cadre party, or elite party,

is a type of political party that was dominant in the nineteenth

century before the introduction of universal suffrage and that was made

up of a collection of individuals or political elites. The French

political scientist Marcel Duverger first distinguished between “cadre”

and “mass” parties, founding his distinction on the differences within

the organisational structures of these two types.

Cadre parties are characterised by minimal and loose organisation, and

are financed by fewer larger monetary contributions typically

originating from outside the party. Cadre parties give little priority

to expanding the party’s membership base, and its leaders are its only

members. The earliest parties, such as the early American political parties, the Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists, are classified as cadre parties.

Mass party

A mass party is a type of political party that developed around cleavages in society and mobilised the ordinary citizens or 'masses' in the political process.

In Europe, the introduction of universal suffrage resulted in the

creation of worker’s parties that later evolved into mass parties; an

example is the German Social Democratic Party.

These parties represented large groups of citizens who had previously

not been represented in political processes, articulating the interests

of different groups in society. In contrast to cadre parties, mass

parties are funded by their members, and rely on and maintain a large

membership base. Further, mass parties prioritise the mobilisation of

voters and are more centralised than cadre parties.

Catch-all party

The catch-all party, also called the 'big tent' party, is a term developed by German-American political scientist Otto Kirchheimer used to describe the parties that developed in the 1950s and 1960s from changes within the mass parties.

Kirchheimer characterised the shift from the traditional mass parties

to catch-all parties as a set of developments including the “drastic

reduction of the party’s ideological baggage” and the "downgrading of

the role of the individual party member".

By broadening their central ideologies into more open-ended ones,

catch-all parties seek to secure the support of a wider section of the

population. Further, the role of members is reduced as catch-all parties

are financed in part by the state or by donations. In Europe, the shift of Christian Democratic parties that were organised around religion into broader centre-right parties epitomises this type.

Cartel party

Cartel parties

are a type of political party that emerged post-1970s and are

characterised by heavy state financing and the diminished role of

ideology as an organising principle. The cartel party thesis was

developed by Richard Katz and Peter Mair who wrote that political parties have turned into "semi-state agencies",

acting on behalf of the state rather than groups in society. The term

'cartel' refers to the way in which prominent parties in government make

it difficult for new parties to enter, as such forming a cartel of

established parties. As with catch-all parties, the role of members in

cartel parties is largely insignificant as parties use the resources of

the state to maintain their position within the political system.

Niche party

Niche

parties are a type of political party that developed on the basis of

the emergence of new cleavages and issues in politics, such as

immigration and the environment.

In contrast to mainstream or catch-all parties, niche parties

articulate an often limited set of interests in a way that does not

conform to the dominant economic left-right divide in politics,

emphasising issues that do not attain prominence within the other

parties.

Further, niche parties do not respond to changes in public opinion to

the extent that mainstream parties do. Examples of niche parties include

Green parties and extreme nationalist parties, such as the Front National in France.

However, over time these parties may lose some of their niche

qualities, instead adopting those of mainstream parties, for example

after entering government.