George Washington (John Trumbull, 1780), with William Lee, Washington's enslaved personal servant

George Washington was a Founding Father of the United States

who owned slaves and became uneasy with the institution of slavery, but

only provided for the emancipation of his slaves after his death. Slavery was ingrained in the economic and social fabric of colonial Virginia,

and Washington inherited his first ten slaves at the age of eleven on

the death of his father in 1743. In adulthood his personal slaveholding

grew through inheritance, purchase and natural increase. In 1759, he

gained control of dower slaves belonging to the Custis estate on his marriage to Martha Dandridge Custis. Washington's early attitudes to slavery reflected the prevailing Virginia planter

views of the day and he demonstrated no moral qualms about the

institution. He became skeptical about the economic efficacy of slavery

before the American Revolutionary War. Although he expressed support in private for the abolition of slavery

by a gradual legislative process after the war, Washington remained

dependent on slave labor. By the time of his death in 1799 there were

317 slaves at his Mount Vernon estate, 124 owned by Washington and the remainder managed by him as his own property but belonging to other people.

Washington was a demanding master. He provided his slaves with

basic food, clothing and accommodation comparable to general practice at

the time but not always adequate, and with medical care. In return, he

expected them to work diligently from sunrise to sunset over the six-day

working week that was standard at the time. Some three-quarters of his

slaves labored in the fields, while the remainder worked at the main

residence as domestic servants and artisans. They supplemented their

diet by hunting, trapping, and growing vegetables in their free time,

and bought extra rations, clothing and housewares with income from the

sale of game and produce. They built their own community around marriage

and family, though because Washington allocated slaves to farms

according to the demands of the business without regard for their

relationships, many husbands lived separately from their wives and

children. Washington used both reward and punishment to encourage and

discipline his slaves, but was constantly disappointed when they failed

to meet his exacting standards. They resisted enslavement by various

means, including theft to supplement food and clothing and as another

source of income, by feigning illness, and by running away.

Washington's first doubts about slavery were entirely economic,

prompted by his transition from tobacco to grain crops in the 1760s

which left him with a costly surplus of slaves. As commander-in-chief of

the Continental Army

in 1775, he initially refused to accept African-Americans, free or

slave, into the ranks, but reversed this position due to the demands of

war. The first indication of moral doubt appeared during efforts to sell

some of his slaves in 1778, when Washington expressed distaste for

selling them at a public venue and his desire that slave families not be

split up as a result of the sale. His public words and deeds at the end

of the American Revolutionary War in 1783 showed no antislavery

sentiments. Politically, Washington was concerned that such a divisive

issue as slavery

should not threaten national unity, and he never spoke publicly about

the institution. Privately, Washington considered freeing all the slaves

he controlled in the mid-1790s, but could not realize this because of

his economic dependence on them and the refusal of his family to

cooperate. His will provided for the emancipation of his slaves, the

only slave-owning Founding Father to do so. Because many of his slaves

were married to Martha's dower slaves, whom he could not legally free,

Washington stipulated that, with the exception of his valet William Lee

who was freed immediately, his slaves be emancipated on the death of

Martha. She freed them in 1801, a year before her own death, but her

dower slaves were passed to her grandchildren and remained in bondage.

Background

First slaves arriving in Virginia

Slavery was introduced into the English colony of Virginia when the first Africans were transported to Point Comfort

in 1619. Those who accepted Christianity became "Christian servants"

with time-limited servitude, or even freed, but this mechanism for

ending bondage was gradually shut down. In 1667, the Virginia Assembly passed a law that barred baptism as a means of conferring freedom. Africans who had been baptised before arriving in Virginia could be granted the status of indentured servant

until 1682, when another law declared them to be slaves. Whites and

people of African descent in the lowest stratum of Virginian society

shared common disadvantages and a common lifestyle, which included

intermarriage until the Assembly made such unions punishable by

banishment in 1691.

In 1671, Virginia counted 6,000 white indentured servants among

its 40,000 population but only 2,000 people of African descent, up to a

third of whom in some counties were free. Towards the end of the 17th

century, English policy shifted in favor of retaining cheap labor rather

than shipping it to the colonies, and the supply of indentured servants

in Virginia began to dry up; by 1715, annual immigration was in the

hundreds, compared with 1,500–2,000 in the 1680s. As tobacco planters

put more land under cultivation, they made up the shortfall in labor

with increasing numbers of slaves. The institution was rooted in race

with the Virginia Slave Codes of 1705,

and from around 1710 the growth in the slave population was fueled by

natural increase. Between 1700 and 1750 the number of slaves in the

colony increased from 13,000 to 105,000, nearly eighty percent of them

born in Virginia.

In Washington's lifetime, slavery was deeply ingrained in the economic

and social fabric of Virginia, where some forty percent of the

population and virtually all African Americans were enslaved.

George Washington was born in 1732, the first child of his father Augustine's

second marriage. Augustine was a tobacco planter with some 10,000 acres

(4,000 ha) of land and 50 slaves. On his death in 1743, he left his

2,500-acre (1,000 ha) Little Hunting Creek to George's older

half-brother Lawrence, who renamed it Mount Vernon. Washington inherited the 260-acre (110 ha) Ferry Farm and ten slaves. He leased Mount Vernon from Lawrence's widow two years after his brother's death in 1752 and inherited it in 1761. He was an aggressive land speculator, and by 1774 he had amassed some 32,000 acres (13,000 ha) of land in the Ohio Country on Virginia's western frontier. At his death he possessed over 80,000 acres (32,000 ha).

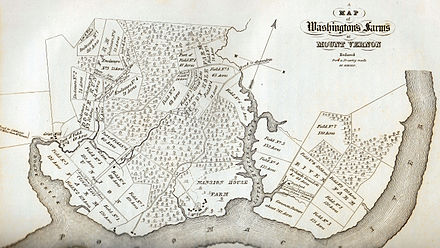

In 1757, he began a program of expansion at Mount Vernon that would

ultimately result in an 8,000-acre (3,200 ha) estate with five separate

farms, on which he initially grew tobacco.

Mount Vernon estate

Agricultural land required labor to be productive, and in the

18th-century American south that meant slave labor. Washington inherited

slaves from Lawrence, acquired more as part of the terms of leasing

Mount Vernon, and inherited slaves again on the death of Lawrence's

widow in 1761. On his marriage in 1759 to Martha Dandridge Custis, Washington gained control of eighty-four dower

slaves. They belonged to the Custis estate and were held in trust by

Martha for the Custis heirs, and although Washington had no legal title

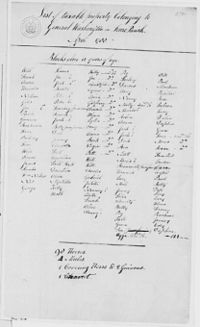

to them, he managed them as his own property. Between 1752 and 1773, he purchased at least seventy-one slaves – men, women and children. He scaled back significantly his purchasing of slaves after the American Revolution but continued to acquire them, mostly through natural increase and occasionally in settlement of debts. In 1786, he listed 216 slaves – 122 men and women and 88 children. – making him one of the largest slaveholders in Fairfax County.

Of that total, 103 belonged to Washington, the remainder being dower

slaves. By the time of Washington's death in 1799, the slave population

at Mount Vernon had increased to 317 people, including 143 children. Of

that total, he owned 124, leased 40 and controlled 153 dower slaves.

Slavery at Mount Vernon

Washington

thought of his workers as part of an extended family with him the

father figure at its head. He displayed elements of both patriarchy and

paternalism in his attitudes to the slaves he controlled. The patriarch

in him expected absolute obedience and manifested itself in a strict,

rigorous control of the slaves and the emotional distance he maintained

from them. There are examples of genuine affection between master and slave, such as was the case with his valet William Lee, but such cases were the exception.

The paternalist in him saw his relationship with his slaves as one of

mutual obligations; he provided for them and they in return served him, a

relationship in which slaves were able to approach Washington with

their concerns and grievances. Paternal masters regarded themselves as generous and deserving of gratitude. When Martha's maid Oney Judge

escaped in 1796, Washington complained about "the ingratitude of the

girl, who was brought up and treated more like a child than a Servant."

George Washington is a

hard master, very severe, a hard husband, a hard father, a hard

governor. From his childhood he always ruled and ruled severely. He was

first brought up to govern slaves, he then governed an army, then a

nation. He thinks hard of all, is despotic in every respect, he

mistrusts every man, thinks every man a rogue and nothing but severity

will do.

Thomas Jefferson, 1799

Although Washington employed a farm manager to run the estate and an

overseer at each of the farms, he was a hands-on manager who ran his

business with a military discipline and involved himself in the minutiae

of everyday work.

During extended absences while on official business, he maintained

close control through weekly reports from the farm manager and

overseers.

He demanded from all of his workers the same meticulous eye for detail

that he exercised himself; a former slave would later recall that the

"slaves...did not quite like" Washington, primarily because "he was so

exact and so strict...if a rail, a clapboard, or a stone was permitted

to remain out of its place, he complained; sometimes in language of

severity."

In Washington's view, "lost labour is never to be regained," and he

required "every labourer (male or female) [do] as much in the 24 hours

as their strength without endangering the health, or constitution will

allow of." He had a strong work ethic and expected the same from his

workers, slave and hired.

He was constantly disappointed with slaves who did not share his

motivation and resisted his demands, leading him to regard them as

indolent and insist that his overseers supervise them closely at all

times.

In 1799, nearly three-quarters of the slaves, over half of them

female, worked in the fields. They were kept busy year round, their

tasks varying with the season. The remainder worked as domestic servants in the main residence or as artisans, such as carpenters, joiners, coopers, spinners and seamstresses. Between 1766 and 1799, seven dower slaves worked at one time or another as overseers.

Slaves were expected to work from sunrise to sunset over a six-day work

week that was standard on Virginia plantations. With two hours off for

meals, their workdays would range between seven and a half hours to

thirteen hours, depending on season. They were given three or four days

off at Christmas and a day each at Easter and Whitsunday. Domestic slaves started early, worked into the evenings and did not necessarily have Sundays and holidays free.

On special occasions when slaves were required to put in extra effort,

such as working through a holiday or bringing in the harvest, they were

paid or compensated with extra time off.

Washington instructed his overseers to treat slaves "with humanity and tenderness" when sick.

Slaves who were less able, through injury, disability or age, were

given light duties, while those too sick to work were generally, though

not always, excused work while they recovered. Washington provided them with good, sometimes costly medical care – when a slave named Cupid fell ill with pleurisy,

Washington had him taken to the main house where he could be better

cared for and personally checked on him throughout the day.

The paternal concern for the welfare of his slaves was mixed with an

economic consideration for the lost productivity arising from sickness

and death among the labor force.

Living conditions

Modern reconstruction of a slave cabin at Mount Vernon

At Mansion House Farm, most slaves were housed in a two-story frame building

known as the "Quarters for Families". This was replaced in 1792 by

brick-built accommodation wings either side of the greenhouse comprising

four rooms in total, each some 600 square feet (56 m2). The Mount Vernon Ladies' Association

have concluded these rooms were communal areas furnished with bunks

that allowed little privacy for the predominantly male occupants. Other

slaves at Mansion House Farm lived over the outbuildings where they

worked or in log cabins.

Such cabins were the standard slave accommodation at the outlying

farms, comparable to the accommodation occupied by the lower strata of

free white society across the Chesapeake area and by slaves on other Virginia plantations. They provided a single room that ranged in size from 168 square feet (15.6 m2) to 246 square feet (22.9 m2) to house a family.

The cabins were often poorly constructed, daubed with mud for draft-

and water-proofing, with dirt floors. Some cabins were built as

duplexes; some single-unit cabins were small enough to be moved on

carts.

There are few sources which shed light on living conditions in these

cabins, but one visitor in 1798 wrote, "husband and wife sleep on a mean

pallet, the children on the ground; a very bad fireplace, some utensils

for cooking, but in the middle of this poverty some cups and a teapot."

Other sources suggest the interiors were smoky, dirty and dark, with

only a shuttered opening for a window and the fireplace for illumination

at night.

Washington provided slaves with a blanket each fall at most,

which they used for their own bedding and which they were required to

use to gather leaves for livestock bedding.

Slaves at the outlying farms were issued with a basic set of clothing

each year, comparable to the clothing issued on other Virginia

plantations. Slaves slept and worked in their clothes, leaving them to

spend many months in garments that were worn, ripped and tattered.

Domestic slaves at the main residence who came into regular contact

with visitors were better clothed; butlers, waiters and body servants

were dressed in a livery

based on the three-piece suit of an 18th-century gentleman, and maids

were provided with finer quality clothing than their counterparts in the

fields.

Washington desired his slaves to be fed adequately but no more. Each slave was provided with a basic daily food ration of one US quart (0.95 l) or more of cornmeal,

up to eight ounces (230 g) of herring and occasionally some meat, a

fairly typical ration for slaves in Virginia that was adequate in terms

of the calorie requirement for a young man engaged in moderately heavy

agricultural labor but nutritionally deficient.

The basic ration was supplemented by slaves' own efforts hunting (for

which some slaves were allowed guns) and trapping game. They grew their

own vegetables in small garden plots they were permitted to maintain in

their own time, on which they also reared poultry.

Washington often tipped slaves on his visits to other estates,

and it is likely that his own slaves were similarly rewarded by visitors

to Mount Vernon. Slaves occasionally earned money through their normal

work or for particular services rendered – for example, Washington

rewarded three of his own slaves with cash for good service in 1775, a

slave received a fee for the care of a mare that was being bred in 1798

and the chef Hercules profited well by selling slops from the presidential kitchen. Slaves also earned money from their own endeavors, by selling to Washington or at the market in Alexandria food they had caught or grown and small items they had made.

They used the proceeds to purchase from Washington or the shops in

Alexandria better clothing, housewares and extra provisions such as

flour, pork, whiskey, tea, coffee and sugar.

Family and community

Interior of the reconstructed slave cabin at Mount Vernon

Although the law did not recognize slave marriages, Washington did,

and by 1799 some two-thirds of the adult slaves at Mount Vernon were

married.

To minimize time lost in getting to the workplace and thus increase

productivity, slaves were accommodated at the farm on which they worked.

Because of the unequal distribution of males and females across the

five farms, slaves often found partners on different farms, and in their

day to day lives husbands were routinely separated from their wives and

children. Only thirty-six of the ninety-six married slaves at Mount

Vernon in 1799 lived together, while thirty-eight had spouses who lived

on separate farms and twenty-two had spouses who lived on other

plantations.

The evidence suggests couples that were separated did not regularly

visit during the week, and doing so prompted complaints from Washington

that slaves were too exhausted to work after such "night walking",

leaving Saturday nights/Sundays and holidays as the main time such

families could spend together.

Despite the stress and anxiety caused by this indifference to family

stability – on one occasion an overseer wrote that the separation of

families "seems like death to them" – marriage was the foundation on

which slaves established their own community, and longevity in these

unions was not uncommon.

Large families that covered multiple generations, along with

their attendant marriages, were part of a slave community-building

process that transcended ownership. Washington's head carpenter Isaac,

for example, lived with his wife Kitty, a dower-slave milkmaid, at

Mansion House Farm. The couple had nine daughters ranging in age from

six to twenty-seven in 1799, and the marriages of four of those

daughters had extended the family to other farms within and outside the

Mount Vernon estate and produced three grandchildren. Children were born into slavery, their ownership determined by the ownership of their mothers.

The value attached to the birth of a slave child, if it was noted at

all, is indicated in the weekly report of one overseer, which stated,

"Increase 9 Lambs & 1 male child of Lynnas." New mothers received a

new blanket and three to five weeks of light duties to recover. An

infant remained with its mother at her place of work.

Older children, the majority of whom lived in single-parent households

in which the mother worked from dawn to dusk, performed small family

chores but were otherwise left to play largely unsupervised until they

reached an age when they could begin to be put to work for Washington,

usually somewhere between eleven and fourteen years old. In 1799, nearly sixty percent of the slave population was under nineteen years old and nearly thirty-five percent under nine.

There is evidence that slaves passed on their African cultural values through telling stories, among them the tales of Br'er Rabbit

which, with their origins in Africa and stories of a powerless

individual triumphing through wit and intelligence over powerful

authority, would have resonated with the slaves.

African-born slaves brought with them some of the religious rituals of

their ancestral home, and there is an undocumented tradition of voodoo

being practiced at one of the Mount Vernon farms. Although the slave condition made it impossible to adhere to the Five Pillars of Islam, some slave names betray a Muslim cultural origin. Anglicans

reached out to American-born slaves in Virginia, and some of the Mount

Vernon slaves are known to have been christened before Washington

acquired the estate. There is evidence in the historical record from

1797 that Mount Vernon slaves had contacts with Baptists, Methodists and Quakers.

The three religions advocated abolition, raising hopes of freedom among

the slaves, and the congregation of the Alexandria Baptist Church,

founded in 1803, included slaves formerly owned by Washington.

Mulattoes

In 1799 there were some twenty mulatto

(mixed race) slaves at Mount Vernon. The probability of paternal

relationships between slaves and hired white workers is indicated by

some surnames: Betty and Tom Davis, probably the children of Thomas

Davis, a white weaver at Mount Vernon in the 1760s; George Young, likely

the son of a man of the same name who was a clerk at Mount Vernon in

1774; and Judge and her sister Delphy, the daughters of Andrew Judge, an

indentured tailor at Mount Vernon in the 1770s and 1780s.

There is evidence to suggest that white overseers – working in close

proximity to slaves under the same demanding master and physically and

socially isolated from their own peer group, a situation that drove some

to drink – indulged in sexual relations with the slaves they

supervised. Some white visitors to Mount Vernon seemed to have expected slave women to provide sexual favors.

The living arrangements left some slave females alone and vulnerable,

and the Mount Vernon research historian Mary V. Thompson writes that

relationships "could have been the result of mutual attraction and

affection, very real demonstrations of power and control, or even

exercises in the manipulation of an authority figure."

Resistance

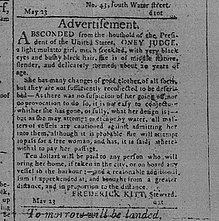

Advertisement placed in the Pennsylvania Gazette after Oney Judge absconded from the President's House in 1796

The frequent comments Washington made about "rogueries" and "old

tricks" indicate the resistance displayed by the slaves against the

system.

The most common act of resistance was theft, so common that Washington

made allowances for it as part of normal wastage. Food was stolen both

to supplement rations and to sell, and Washington believed the selling

of tools was another source of income for slaves. Because cloth and

clothing were commonly stolen, Washington required seamstresses to show

the results of their work and the leftover scraps before issuing them

with more material. Sheep were washed before shearing to prevent the

theft of wool, and storage areas were kept locked and keys left with

trusted individuals.

In 1792, Washington ordered the culling of slaves' dogs he believed

were being used in a spate of livestock theft and ruled that slaves who

kept dogs without authorization were to be "severely punished" and their

dogs hanged.

Another means by which slaves resisted, one that was virtually

impossible to prove, was feigning illness. Over the years Washington

became increasingly skeptical about absenteeism due to sickness among

his slaves and concerned about the diligence or ability of his overseers

in recognizing genuine cases. Between 1792 and 1794, while Washington

was away from Mount Vernon as President, the number of days lost to

sickness increased tenfold compared to 1786, when he was resident at

Mount Vernon and able to control the situation personally. In one case,

Washington suspected a slave of frequently avoiding work over a period

of decades through acts of deliberate self harm.

Slaves asserted some independence and frustrated Washington by the pace and quality of their work. In 1760, Washington noted that four of his carpenters quadrupled their output of timber under his personal supervision.

Thirty-five years later, he described his carpenters as an "idle...set

of rascals" who would take a month or more to complete at Mount Vernon

work that was being done in two or three days in Philadelphia.

The output of seamstresses dropped off when Martha was away, and

spinners found they could slacken by playing the overseers off against

her.

Tools were regularly lost or damaged, thus stopping work, and

Washington despaired of employing innovations that might improve

efficiency because he believed the slaves were too clumsy to operate the

new machinery involved.

The most emphatic act of resistance was to run away, and between

1760 and 1799 at least forty-seven slaves under Washington's control did

so. Seventeen of these, fourteen men and three women, escaped to a British warship that anchored in the Potomac River near Mount Vernon in 1781.

In general, the best chance of success lay with second- or

third-generation African-American slaves who had good English, possessed

skills that would allow them to support themselves as free people and

were in close enough contact with their masters to receive special

privileges. Thus it was that Judge, an especially talented seamstress,

and Hercules escaped in 1796 and 1797 respectively and eluded recapture.

Washington took seriously the recapture of fugitives, and in three

cases an escaped slave was sold off in the West Indies after recapture,

effectively a death sentence in the severe conditions slaves had to

endure there.

Control

Slavery was a system

in which enslaved people lived in fear; fear of being sold, fear of

being separated from their families or their children or their parents,

fear of not being in control of their bodies or their lives, fear of

never knowing freedom. No matter what their clothing was like, no matter

what food they ate, no matter what their quarters looked like, enslaved

people lived with that fear. And that was the psychological violence of

slavery. That's how slave owners maintained control over enslaved

people.

Jessie MacLeodAssociate Curator

George Washington's Mount Vernon

Washington used both reward and punishment to encourage discipline and productivity in his slaves.

In one case, he suggested "admonition and advice" would be more

effective than "further correction", and he occasionally appealed to a

slave's sense of pride to encourage better performance. Rewards in the

form of better blankets and clothing fabric were given to the "most

deserving", and there are examples of cash payments being awarded for

good behavior.

He opposed the use of the lash in principle, but saw the practice as a

necessary evil and sanctioned its occasional use, generally as a last

resort, on both male and female slaves if they did not, in his words,

"do their duty by fair means."

There are accounts of carpenters being whipped in 1758 when the

overseer "could see a fault", of a slave called Jemmy being whipped for

stealing corn and escaping in 1773 and of a seamstress called Charlotte

being whipped in 1793 by an overseer "determined to lower Spirit or skin

her Back" for impudence and refusing to work.

Washington regarded the "passion" with which one of his overseers

administered floggings to be counter-productive, and Charlotte's

protest that she had not been whipped in fourteen years indicates the

frequency with which physical punishment was used.

Whippings were administered by overseers after review, a system

Washington required to ensure slaves were spared capricious and extreme

punishment. Washington did not himself flog slaves, but he did on

occasion lash out in a flash of temper with verbal abuse and physical

violence when they failed to perform as he expected.

Contemporaries generally described Washington as having a calm

demeanor, but there are several reports from those who knew him

privately that talk of his temper. One wrote that "in private and

particularly with his servants, its violence sometimes broke out."

Another reported that Washington's servants "seemed to watch his eye and

to anticipate his every wish; hence a look was equivalent to a

command."

Threats of demotion to fieldwork, corporal punishment and being shipped

to the West Indies were part of the system by which he controlled his

slaves.

Evolution of Washington's attitudes

Life of George Washington: The Farmer by Junius Brutus Stearns (1851)

Washington's early views on slavery were no different from any Virginia planter of the time. He demonstrated no moral qualms about the institution and referred to his slaves as "a Species of Property."

The economics of slavery prompted the first doubts in Washington about

the institution, marking the beginning of a slow evolution in his

attitude towards it. By 1766, he had transitioned his business from the

labor-intensive planting of tobacco to the less demanding farming of

grain crops. His slaves were employed on a greater variety of tasks that

needed more skills than tobacco planting required of them; as well as

the cultivation of grains and vegetables, they were employed in cattle

herding, spinning, weaving and carpentry. The transition left Washington

with a surplus of slaves and revealed to him the inefficiencies of the

slave labor system.

There is little evidence that Washington seriously questioned the ethics of slavery before the Revolution.

In the 1760s he often participated in tavern lotteries, events in which

defaulters' debts were settled by raffling off their assets to a

high-spirited crowd.

In 1769, Washington co-managed one such lottery in which fifty-five

slaves were sold, among them six families and five females with

children. The more valuable married males were raffled together with

their wives and children; less valuable slaves were separated from their

families into different lots. Robin and Bella, for example, were

raffled together as husband and wife while their children,

twelve-year-old Sukey and seven-year-old Betty, were listed in a

separate lot. Only chance dictated whether the family would remain

together, and with 1,840 tickets on sale the odds were not good.

The historian Henry Wiencek

concludes that the repugnance Washington felt at this cruelty in which

he had participated prompted his decision not to break up slave families

by sale or purchase, and marks the beginning of a transformation in

Washington's thinking about the morality of slavery.

Wiencek writes that in 1775 Washington took more slaves than he needed

rather than break up the family of a slave he had agreed to accept in

payment of a debt. The historians Philip D. Morgan and Peter Henriques

are skeptical of Wiencek's conclusion and believe there is no evidence

of any change in Washington's moral thinking at this stage. Morgan

writes that in 1772, Washington was "all business" and "might have been

buying livestock" in purchasing more slaves who were to be, in

Washington's words, "strait Limb'd, & in every respect strong &

likely, with good Teeth & good Countenance." Morgan gives a

different account of the 1775 purchase, writing that Washington resold

the slave because of the slave's resistance to being separated from

family and that the decision to do so was "no more than the conventional

piety of large Virginia planters who usually said they did not want to

break up slave families – and often did it anyway."

American Revolution

Washington's taxable property in April 1788: 121 slaves, 98 horses, 4 mules and a chariot

From the late 1760s, Washington became increasingly radicalized

against the North American colonies' subservient status within the British Empire. In 1774 he was a key participant in the adoption of the Fairfax Resolves which, alongside the assertion of colonial rights, condemned the transatlantic slave trade on moral grounds. He began to express the growing rift with Great Britain

in terms of slavery, stating in the summer of 1774 that the British

authorities were "endeavouring by every piece of Art & despotism to

fix the Shackles of Slavry [sic]" upon the colonies. Two years later, on taking command of the Continental Army at Cambridge at the start of the American Revolutionary War,

he wrote in orders to his troops that "it is a noble Cause we are

engaged in, it is the Cause of virtue and mankind...freedom or Slavery

must be the result of our conduct."

The hypocrisy inherent in slave owners characterizing a war of

independence as a struggle for their own freedom from slavery was not

lost on the British writer Samuel Johnson, who asked, "How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?"

Washington shared the common southern concern about arming

African-Americans or slaves and initially refused to accept either into

the ranks of the Continental Army. He reversed his position on the

recruitment of free African-Americans when the royal governor of

Virginia, Lord Dunmore, issued a proclamation

in November 1775 offering freedom to rebel-owned slaves who enlisted in

the British forces. Three years later and facing acute manpower

shortages, Washington approved a Rhode Island initiative to raise a

battalion of African Americans.

Washington gave a cautious response to a 1779 proposal from his young aide John Laurens

for the recruitment of 3,000 South Carolinian slaves who would be

rewarded with emancipation. He was concerned that such a move would

prompt the British to do the same, leading to an arms race in which the

Americans would be at a disadvantage, and that it would promote

discontent among those who remained enslaved.

During the war, some 5,000 African-Americans served in a Continental

Army that was more integrated than any American force before the Vietnam War,

and another 1,000 served on American warships. They represented less

than three percent of all American forces mobilized, though in 1778 they

provided between six and thirteen percent of the Continental Army.

The first indication of a shift in Washington's thinking on

slavery appears during the war, in correspondence of 1778 and 1779 with Lund Washington, who managed Mount Vernon in Washington's absence.

In the exchange of letters, a conflicted Washington expressed a desire

"to get quit of Negroes", but made clear his reluctance to sell them at a

public venue and his wish that "husband and wife, and Parents and

children are not separated from each other."

His determination not to separate families became a major complication

in his deliberations on the sale, purchase and, in due course,

emancipation of his own slaves.

His restrictions put Lund in a difficult position with two female

slaves he had already all but sold in 1778, and Lund's irritation was

evident in his request to Washington for clear instructions.

Despite Washington's reluctance to break up families, there is little

evidence that moral considerations played any part in his thinking at

this stage. He sought to liberate himself from an economically unviable

system, not to liberate his slaves. They were still a property from

which he expected to profit. During a period of severe wartime

depreciation, the question was not whether to sell his slaves, but when,

where and how best to sell them. Lund sold nine slaves, including the

two females, in January 1779.

Washington's actions at the war's end reveal little in the way of

antislavery inclinations. He was anxious to recover his own slaves and

refused to consider compensation for the upwards of 80,000 slaves

evacuated by the British, insisting without success that the British

return them to their owners.

Before resigning his commission in 1783, Washington took the

opportunity to give his opinion on the opportunities and challenges that

faced the new nation in his Circular to the States, in which he made not one mention of slavery.

Confederation years

The Marquis de Lafayette

Emancipation became a major issue in Virginia after liberalization of the manumission

law in 1782. Inspired by the rhetoric that had driven the revolution,

it became popular to free slaves. The free African-American population

in Virginia rose from some 3,000 to more than 20,000 between 1780 and

1800, when the proslavery interest re-asserted itself.

The historian Kenneth Morgan writes, "..the revolutionary war was the

crucial turning-point in [Washington's] thinking about slavery. After

1783...he began to express inner tensions about the problem of slavery

more frequently, though always in private..." Although Philip Morgan identifies several turning points and believes no single one was pivotal, most historians agree the Revolution was central to the evolution of Washington's attitudes on slavery.

It is likely that revolutionary rhetoric about the rights of men, the

close contact with young antislavery officers who served with

Washington – such as Laurens, the Marquis de Lafayette and Alexander Hamilton – and the influence of northern colleagues were contributory factors in that process.

Washington was drawn into the postwar abolitionist discourse

through his contacts with antislavery friends, their transatlantic

network of leading abolitionists and the literature produced by the

antislavery movement,

though he was reluctant to volunteer his own opinion on the matter and

generally did so only when the subject was first raised with him.

At his death, Washington's extensive library included at least

seventeen publications on slavery. Six of them had been collated into an

expensively bound volume titled Tracts on Slavery, indicating that he attached some importance to that selection. Five of the six were published in or after 1788.

All six shared common themes that slaves first had to be educated about

the obligations of liberty before they could be emancipated, a belief

Washington is reported to have expressed himself in 1798, and that

abolition should be realized by a gradual legislative process, an idea

that began to appear in Washington's correspondence during the Confederation period.

Washington was not impressed by what Dorothy Twohig – a former editor-in-chief of The Washington Papers –

described as the "imperious demands" and "evangelical piety" of Quaker

efforts to advance abolition, and in 1786 he complained about their

"tamper[ing] with & seduc[ing]" slaves who "are happy & content

to remain with their present masters."

Only the most radical of abolitionists called for immediate

emancipation. The disruption to the labor market and the care of the

elderly and infirm would have created enormous problems. Large numbers

of unemployed poor, of whatever color, was a cause for concern in

18th-century America, to the extent that expulsion and foreign

resettlement was often part of the discourse on emancipation.

A sudden end to slavery would also have caused a significant financial

loss to slaveowners whose human property represented a valuable asset.

Gradual emancipation was seen as a way of mitigating against such a loss

and reducing opposition from those with a financial self-interest in

maintaining slavery.

In 1783, Lafayette proposed a joint venture to establish an

experimental settlement for freed slaves which, with Washington's

example, "might render it a general practise," but Washington demurred.

As Lafayette forged ahead with his plan, Washington offered

encouragement but expressed concern in 1786 about "much inconvenience

and mischief" an abrupt emancipation might generate, and he gave no

tangible support to the idea. Washington privately expressed support for emancipation to prominent Methodists Thomas Coke and Francis Asbury

in 1785, but declined to sign their petition. Although he spoke to

other leading Virginians about his sentiments and promised to write in

support if the petition was considered in the Virginia Assembly, nothing

further came of it.

Henriques identifies Washington's concern for the judgement of

posterity as a significant factor in Washington's thinking on slavery,

writing, "No man had a greater desire for secular immortality, and

[Washington] understood that his place in history would be tarnished by

his ownership of slaves."

Philip Morgan similarly identifies the importance of Washington's

driving ambition for fame and public respect as a man of honor; in December 1785, the Quaker and fellow Virginian Robert Pleasants

"[hit] Washington where it hurt most", Morgan writes, when he told

Washington that to remain a slaveholder would forever tarnish his

reputation.

In correspondence the next year, Washington expressed "great

repugnance" at buying slaves, stated that he would not buy any more

"unless some peculiar circumstances should compel me to it" and made

clear his desire to see the institution of slavery ended by a gradual

legislative process.

Washington did not let principle interfere with business; he

still needed labor to work his farms, and there was little alternative

to slavery. Hired labor south of Pennsylvania was scarce and expensive,

and the Revolution had cut off the supply of indentured servants and

convict labor from Great Britain.

Washington significantly reduced his slave purchases after the war,

though it is not clear whether this was a moral or practical decision;

he repeatedly stated that his inventory and its potential progeny were

adequate for his current and foreseeable needs. Nevertheless, he negotiated with John Mercer to accept six slaves in payment of a debt in 1786 and expressed to Henry Lee a desire to purchase a bricklayer the next. In 1788, Washington acquired thirty-three slaves from the estate of Bartholomew Dandridge in settlement of a debt and left them with Dandridge's widow on her estate at Pamocra, New Kent County, Virginia. Later the same year, he declined a suggestion from the leading French abolitionist Jacques Brissot

to form and become president of an abolitionist society in Virginia,

stating that although he was in favor of such a society and would

support it, the time was not yet right to confront the issue.

Presidential years

The unfortunate

condition of the persons, whose labour in part I employed, has been the

only unavoidable subject of regret. To make the Adults among them as

easy & as comfortable in their circumstances as their actual state

of ignorance & improvidence would admit; & to lay a foundation

to prepare the rising generation for a destiny different from that in

which they were born; afforded some satisfaction to my mind, & could

not I hoped be displeasing to the justice of the Creator.

Statement attributed to George Washington that appears in the notebook of David Humphreys, c.1788/1789

Another complication for Washington's personal position on slavery

was the political ramifications of emancipation. He presided over the Constitutional Convention

in 1787, during which it became obvious just how explosive the issue

was and how willing the antislavery faction was to accept the

preservation of slavery to ensure national unity and the establishment

of a strong federal government. The support of the southern states for

the new constitution was secured by granting them concessions that

protected slavery, including the Three-Fifths Compromise and the Fugitive Slave Clause,

plus clauses that guaranteed the transatlantic slave trade for at least

twenty years and federal aid for the suppression of any slave

rebellion.

Washington's preeminent position ensured that any actions he took

with regard to his own slaves would become a statement in a national

debate about slavery that threatened to divide the country. Wiencek

suggests Washington considered making precisely such a statement on

taking up the presidency in 1789. A passage in the notebook of

Washington's biographer David Humphreys

dated to late 1788 or early 1789 recorded a statement that resembled

the emancipation clause in Washington's will a decade later. Wiencek

argues the passage was a draft for a public announcement Washington was

considering in which he would declare the emancipation of some of his

slaves. It marks, Wiencek believes, a moral epiphany in Washington's

thinking, the moment he decided not only to emancipate his slaves but

also to use the occasion to set the example Lafayette had urged in 1783. Other historians dispute Wiencek's conclusion; Henriques and Joseph Ellis

concur with Philip Morgan's opinion that Washington experienced no

epiphanies in a "long and hard-headed struggle" in which there was no

single turning point. Morgan argues that Humphreys' passage is the

"private expression of remorse" from a man unable to extricate himself

from the "tangled web" of "mutual dependency" on slavery, and that

Washington believed public comment on such a divisive subject was best

avoided for the sake of national unity.

As president

President George Washington by Gilbert Stuart (1795)

Washington took up the presidency at a time when revolutionary

sentiment against slavery was giving way to a resurgence of proslavery

interests. No state considered making slavery an issue during the

ratification of the new constitution, southern states reinforced their

slavery legislation and prominent antislavery figures were muted about

the issue in public. Washington understood there was little widespread

organized support for abolition.

He had a keen sense both of the fragility of the fledgling Republic and

of his place as a unifying figure, and he was determined not to

endanger either by confronting an issue as divisive and entrenched as

slavery.

He was president of a government that passed a resolution in 1790

affirming states' rights to regulate treatment of slaves and legislate

on slavery free of congressional interference, provided materiel and

financial support for French efforts to suppress the Saint Domingue slave revolt in 1791 and implemented the proslavery Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. He also signed into law the Slave Trade Act of 1794 that sought to limit American involvement in the international slave trade.

Washington never spoke publicly on the issue of slavery during his

eight years as president, nor did he respond to, much less act upon, any

of the antislavery petitions he received. He described a 1790 Quaker

petition to Congress

urging an immediate end to the slave trade as "an illjudged piece of

business" that "occasioned a great waste of time." The issue of slavery

was not mentioned in either his last address to Congress or his Farewell Address.

Late in his presidency, Washington told his Secretary of State, Edmund Randolph, that in the event of a confrontation between North and South, he had "made up his mind to remove and be of the Northern."

In 1798, he imagined just such a conflict when he said, "I can clearly

foresee that nothing but the rooting out of slavery can perpetuate the

existence of our union."

But there is no indication Washington ever favored an immediate end to

slavery. His abolitionist aspirations for the nation were confined to

the hope that slavery would disappear naturally over time with the prohibition of slave imports in 1808, the earliest date such legislation could be passed as agreed at the Constitutional Convention.

As Virginia farmer

As

well as political caution, economic imperatives remained an important

consideration with regard to Washington's personal position as a

slaveholder and his efforts to free himself from his dependency on

slavery. He was one of the largest debtors in Virginia at the end of the war,

and by 1787 the business at Mount Vernon had failed to make a profit

for more than a decade. Persistently poor crop yields due to pestilence

and poor weather, the cost of renovations at his Mount Vernon residence,

the expense of entertaining a constant stream of visitors, the failure

of Lund to collect rent from Washington's tenant farmers and wartime

depreciation all helped to make Washington cash poor.

It is demonstrably

clear that on this Estate I have more working Negroes by a full moiety,

than can be employed to any advantage in the farming system; and I shall

never turn to Planter thereon...To sell the surplus I cannot, because I

am principled against this kind of traffic in the human species...

George Washington to Robert Lewis, August 17, 1799

The overheads of maintaining a surplus of slaves, including the care

of the young and elderly, made a substantial contribution to his

financial difficulties.

In 1786, the ratio of productive to non-productive slaves was

approaching 1:1, and the c. 7,300-acre (3,000 ha) Mount Vernon estate

was being operated with 122 working slaves. Although the

productive/non-productive ratio had improved by 1799 to around 2:1, the

Mount Vernon estate had grown by only 10 percent to some 8,000 acres

(3,200 ha) while the working slave population had grown by 65 percent to

201. It was a trend that threatened to bankrupt Washington.

The slaves Washington had bought early in the development of his

business were beyond their prime and nearly impossible to sell, and from

1782 Virginia law made slaveowners liable for the financial support of

slaves they freed who were too young, too old or otherwise incapable of

working.

During his second term, Washington began planning for a retirement that would provide him "tranquillity with a certain income." In December 1793, he sought the aid of the British agriculturalist Arthur Young in finding farmers to whom he would lease all but one of his farms, on which his slaves would then be employed as laborers. The next year, he instructed his secretary Tobias Lear

to sell his western lands, ostensibly to consolidate his operations and

put his financial affairs in order. Washington concluded his

instructions with a private passage in which he expressed repugnance at

owning slaves and declared that the principal reason for selling the

land was to raise the finances that would allow him to liberate them. It is the first clear indication that Washington's thinking had shifted from selling his slaves to freeing them.

In November the same year, Washington declared in a letter to his

friend and neighbor Alexander Spotswood that he was "...principled agt. [sic] selling Negroes, as you would Cattle in the market..."

In 1795 and 1796, Washington devised a complicated plan that

involved renting out his western lands to tenant farmers to whom he

would lease his own slaves, and a similar scheme to lease the dower

slaves he controlled to Dr. David Stuart

for work on Stuart's Eastern Shore plantation. This plan would have

involved breaking up slave families, but it was designed with an end

goal of raising enough finances to fund their eventual emancipation (a

detail Washington kept secret) and prevent the Custis heirs from

permanently splitting up families by sale.

None of these schemes could be realized because of his failure to sell

or rent land at the right prices, the refusal of the Custis heirs to

agree to them and his own reluctance to separate families.

Wiencek speculates that, because Washington gave such serious

consideration to freeing his slaves knowing full well the political

ramifications that would follow, one of his goals was to make a public

statement that would sway opinion towards abolition.

Philip Morgan argues that Washington freeing his slaves while President

in 1794 or 1796 would have had no profound effect, and would have been

greeted with public silence and private derision by white southerners.

As Washington subordinated his desire for emancipation to his

efforts to secure financial independence, he took care to retain his

slaves.

From 1791, he arranged for those who served in his personal retinue in

Philadelphia while he was President to be rotated out of the state

before they became eligible for emancipation after six months residence

per Pennsylvanian law.

Not only would Washington have been deprived of their services if they

were freed, most of the slaves he took with him to Philadelphia were

dower slaves, which meant that he would have had to compensate the

Custis estate for the loss. Because of his concerns for his public image

and that the prospect of emancipation would generate discontent among

the slaves before they became eligible for emancipation, he instructed

that they be shuffled back to Mount Vernon "under pretext that may

deceive both them and the Public."

Washington spared no expense in efforts to recover Hercules and

Judge when they absconded. In Judge's case, Washington persisted for

three years. He tried to persuade her to return when his agent

eventually tracked her to New Hampshire, but refused to promise her

freedom after his death; "However well disposed I might be to a gradual

emancipation," he said, "or even to an entire emancipation of that

description of People (if the latter was in itself practicable at this

moment) it would neither be politic or just to reward unfaithfulness

with a premature preference." Both Hercules and Judge eluded capture.

Washington's search for a new chef to replace Hercules in 1797 is the

last known instance in which he considered buying a slave, despite his

resolve "never to become the Master of another Slave by purchase"; in

the end he chose to hire a white chef.

Posthumous emancipation

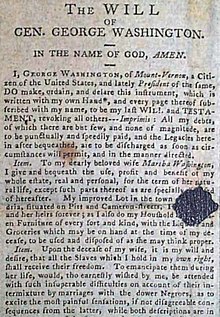

Washington's will published in the Connecticut Journal, February 20, 1800

In July 1799, five months before his death, Washington wrote his

will, in which he stipulated that his slaves should be freed. In the

months that followed, he considered a plan that betrayed a continuing

prioritization of profit above his concerns about the institution of

slavery. The plan involved repossessing tenancies in Berkeley and Frederick

Counties and transferring half of his Mount Vernon slaves to work them.

It would, Washington hoped, "yield more nett profit" which might

"benefit myself and not render the [slaves'] condition worse", despite

the disruption such relocation would have had on the slave families. The

plan died with Washington on December 14, 1799.

Washington's slaves were the subjects of the longest provisions

in the twenty-nine-page will, taking three pages in which his

instructions were more forceful than in the rest of the document. His

valet, William Lee, was freed immediately and his remaining 123 slaves

were to be emancipated on the death of Martha.

The deferral was intended to postpone the pain of separation that would

occur when his slaves were freed but their spouses among the dower

slaves remained in bondage, a situation which affected twenty couples

and their children. It is possible Washington hoped Martha and her heirs

who would inherit the dower slaves would solve this problem by

following his example and emancipating them. Those too old or infirm to work were to be supported by his estate, as mandated by state law.

Washington went beyond the legal requirement to support and

maintain younger slaves until adulthood, stipulating that those children

whose education could not be undertaken by parents were to be taught

reading, writing and a useful trade by their masters and then be freed

at the age of twenty-five.

He was particularly pointed in forbidding the sale or transportation of

any of his slaves out of Virginia before their emancipation. Including the Dandridge slaves, who were to be emancipated under similar terms, more than 160 slaves would be freed.

Although Washington was not alone among Virginian slaveowners in

freeing their slaves, he was unusual for doing it so late, after the

post-revolutionary support for emancipation in Virginia had faded. He

was also unusual for being the only slaveowning Founding Father to do

so.

Aftermath

Slave burial ground memorial at Mount Vernon

Any hopes Washington may have had that his example and prestige would

influence the thinking of others, including his own family, proved to

be unfounded. His action was ignored by southern slaveholders, and

slavery continued at Mount Vernon. Already from 1795, dower slaves were being transferred to Martha's three granddaughters as the Custis heirs married.

Martha felt threatened by the fact that she was surrounded with slaves

whose freedom depended on her death and freed her late husband's slaves

on January 1, 1801.

Able-bodied slaves were freed and left to support themselves and their families.

Within a few months, almost all of Washington's former slaves had left

Mount Vernon, leaving 121 adult and working-age children still working

the estate. Five freedwomen were listed as remaining: an unmarried

mother of two children; two women, one of them with three children,

married to Washington slaves too old to work; and two women who were

married to dower slaves. William Lee remained at Mount Vernon, where he worked as a shoemaker. After Martha's death on May 22, 1802, most of the remaining dower slaves passed to her grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, to whom she bequeathed the only slave she held in her own name.

There are few records of how the newly freed slaves fared.

Custis later wrote that "although many of them, with a view to their

liberation, had been instructed in mechanic trades, yet they succeeded

very badly as freemen; so true is the axiom, 'that the hour which makes

man a slave, takes half his worth away'." The son-in-law of Custis's

sister wrote in 1853 that the descendants of those who remained slaves,

many of them now in his possession, had been "prosperous, contented and

happy," while those who had been freed had led a life of "vice,

dissipation and idleness" and had, in their "sickness, age and poverty",

become a burden to his in-laws.

Such reports were influenced by the innate racism of the well-educated,

upper-class authors and ignored the social and legal impediments that

prejudiced the chances of prosperity for former slaves, which included

laws that made it illegal to teach freedpeople to read and write and, in

1806, required newly freed slaves to leave the state.

There is evidence that some of Washington's former slaves were

able to buy land, support their families and prosper as free people. By

1812, Free Town in Truro Parish,

the earliest known free African-American settlement in Fairfax County,

contained seven households of former Washington slaves. By the mid

1800s, a son of Washington's carpenter Davy Jones and two grandsons of

his postilion

Joe Richardson had each bought land in Virginia. Francis Lee, younger

brother of William, was well known and respected enough to have his

obituary printed in the Alexandria Gazette on his death at Mount

Vernon in 1821. Sambo Anderson – who hunted game, as he had while

Washington's slave, and prospered for a while by selling it to the most

respectable families in Alexandria – was similarly noted by the Gazette when he died near Mount Vernon in 1845. Research published in 2019 has concluded that Hercules worked as a cook in New York, where he died on May 15, 1812.

A decade after Washington's death, the Pennsylvanian jurist Richard Peters

wrote that Washington's servants "were devoted to him; and especially

those more immediately about his person. The survivors of them still

venerate and adore his memory." In his old age, Anderson said he was "a

much happier man when he was a slave than he had ever been since,"

because he then "had a good kind master to look after all my wants, but

now I have no one to care for me."

When Judge was interviewed in the 1840s, she expressed considerable

bitterness, not at the way she he had been treated as a slave, but at

the fact that she had been enslaved. When asked, having experienced the

hardships of being a freewoman and having outlived both husband and

children, whether she regretted her escape, she replied, "No, I am free,

and have, I trust, been made a child of God by [that] means."

Political legacy

Washington's will was both private testament and public statement on the institution.

It was published widely – in newspapers nationwide, as a pamphlet

which, in 1800 alone, extended to thirteen separate editions, and

included in other works – and became part of the nationalist narrative.

In the eulogies of the antislavery faction, the inconvenient fact of

Washington's slaveholding was downplayed in favor of his final act of

emancipation. Washington "disdained to hold his fellow-creatures in

abject domestic servitude," wrote the Massachusetts Federalist Timothy Bigelow

before calling on "fellow-citizens in the South" to emulate

Washington's example. In this narrative, Washington was a

proto-abolitionist who, having added the freedom of his slaves to the

freedom from British slavery he had won for the nation, would be

mobilized to serve the antislavery cause.

An alternative narrative more in line with proslavery sentiments

embraced rather than excised Washington's ownership of slaves.

Washington was cast as a paternal figure, the benevolent father not only

of his country but also of a family of slaves bound to him by affection

rather than coercion. In this narrative, slaves idolized Washington and wept at his deathbed, and in an 1807 biography, Aaron Bancroft wrote, "In domestick [sic] and private life, he blended the authority of the master with the care and kindness of the guardian and friend." The competing narratives allowed both North and South to claim Washington as the father of their countries during the American Civil War that ended slavery more than half a century after his death.

Memorial

In

1929, a plaque was embedded in the ground at Mount Vernon less than 50

yards (45 m) from the crypt housing the remains of Washington and

Martha, marking a plot neglected by both groundsmen and tourist guides

where slaves had been buried in unmarked graves. The inscription read,

"In memory of the many faithful colored servants of the Washington

family, buried at Mount Vernon from 1760 to 1860. Their unidentified

graves surround this spot." The site remained untended and ignored in

the visitor literature until the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association

erected a more prominent monument surrounded with plantings and

inscribed, "In memory of the Afro Americans who served as slaves at

Mount Vernon this monument marking their burial ground dedicated

September 21, 1983." In 1985, a ground-penetrating radar

survey identified sixty-six possible burials. As of late 2017, an

archaeological project begun in 2014 has identified, without disturbing

the contents, sixty-three burial plots in addition to seven plots known

before the project began.