White supremacy or white supremacism is the racist belief that white people are superior to people of other races and therefore should be dominant over them. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine of scientific racism and often relies on pseudoscientific arguments. Like most similar movements such as neo-Nazism, white supremacists typically oppose members of other races as well as Jews.

The term is also used to describe a political ideology that perpetuates and maintains the social, political, historical, or institutional domination by white people (as evidenced by historical and contemporary sociopolitical structures such as the Atlantic slave trade, Jim Crow laws in the United States, the set of "White Australia" policies from the 1890s until the mid-1970s, and apartheid in South Africa). Different forms of white supremacism put forth different conceptions of who is considered white, and different groups of white supremacists identify various racial and cultural groups as their primary enemy.

In academic usage, particularly in usage which draws on critical race theory or intersectionality, the term "white supremacy" can also refer to a political or socioeconomic system, in which white people enjoy a structural advantage (privilege) over other ethnic groups, on both a collective and individual level.

The term is also used to describe a political ideology that perpetuates and maintains the social, political, historical, or institutional domination by white people (as evidenced by historical and contemporary sociopolitical structures such as the Atlantic slave trade, Jim Crow laws in the United States, the set of "White Australia" policies from the 1890s until the mid-1970s, and apartheid in South Africa). Different forms of white supremacism put forth different conceptions of who is considered white, and different groups of white supremacists identify various racial and cultural groups as their primary enemy.

In academic usage, particularly in usage which draws on critical race theory or intersectionality, the term "white supremacy" can also refer to a political or socioeconomic system, in which white people enjoy a structural advantage (privilege) over other ethnic groups, on both a collective and individual level.

History

White supremacy has ideological foundations that date back to 17th-century scientific racism, the predominant paradigm of human variation that helped shape international relations and racial policy from the latter part of the Age of Enlightenment until the late 20th century (marked by decolonization and the abolition of apartheid in South Africa in 1991, followed by that country's first multiracial elections in 1994).

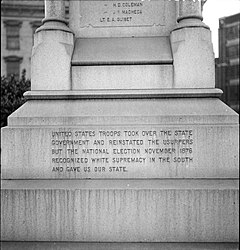

The Battle of Liberty Place monument in Louisiana was erected in 1891 by the white-dominated New Orleans government. An inscription added in 1932 states that the 1876 US Presidential Election "recognized white supremacy in the South and gave us our state". It was removed in 2017 and placed in storage.

Ku Klux Klan parade in Washington, D.C. in 1926

United States

White supremacy was dominant in the United States both before and after the American Civil War, and it also persisted for decades after the Reconstruction Era. In the antebellum South, this included the holding of African Americans in chattel slavery, in which four million of them were denied freedom. The outbreak of the Civil War saw the desire to uphold white supremacy being cited as a cause for state secession and the formation of the Confederate States of America. In an editorial about Native Americans in 1890, author L. Frank Baum wrote: "The Whites, by law of conquest,

by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and

the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total

annihilation of the few remaining Indians."

The Naturalization Act of 1790 limited U.S. citizenship to whites only. In some parts of the United States, many people who were considered non-white were disenfranchised,

barred from government office, and prevented from holding most

government jobs well into the second half of the 20th century. Professor

Leland T. Saito of the University of Southern California

writes: "Throughout the history of the United States, race has been

used by whites for legitimizing and creating difference and social,

economic and political exclusion."

The denial of social and political freedom to minorities continued into the mid-20th century, resulting in the civil rights movement. Sociologist Stephen Klineberg has stated that U.S. immigration laws prior to 1965 clearly declared "that Northern Europeans are a superior subspecies of the white race". The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 opened entry to the U.S. to immigrants other than traditional Northern European and Germanic groups, and significantly altered the demographic mix in the U.S as a result. Many U.S. states banned interracial marriage through anti-miscegenation laws until 1967, when these laws were invalidated by the Supreme Court of the United States' decision in Loving v. Virginia.

These mid-century gains had a major impact on white Americans'

political views; segregation and white racial superiority, which had

been publicly endorsed in the 1940s, became minority views within the

white community by the mid-1970s, and continued to decline into 1990s

polls to a single-digit percentage. For sociologist Howard Winant, these shifts marked the end of "monolithic white supremacy" in the United States.

After the mid-1960s, white supremacy remained an important ideology to the American far-right. According to Kathleen Belew, a historian of race and racism in the United States, white militancy shifted after the Vietnam War from supporting the existing racial order to a more radical position—self-described as "white power" or "white nationalism"—committed to overthrowing the United States government and establishing a white homeland. Such anti-government militia

organizations are one of three major strands of violent right-wing

movements in the United States, with white supremacist groups (such as

the Ku Klux Klan, neo-Nazi organizations, and racist skinheads) and a religious fundamentalist movement (such as Christian Identity) being the other two.

Howard Winant writes that, "On the far right the cornerstone of white

identity is belief in an ineluctable, unalterable racialized difference

between whites and nonwhites." In the view of philosopher Jason Stanley,

white supremacy in the United States is an example of the fascist

politics of hierarchy, in that it "demands and implies a perpetual

hierarchy" in which whites dominate and control non-whites.

Some academics argue that outcomes from the 2016 United States Presidential Election reflect ongoing challenges with white supremacy. Psychologist Janet Helms

suggested that the normalizing behaviors of social institutions of

education, government, and healthcare are organized around the

"birthright of...the power to control society's resources and determine

the rules for [those resources]". Educators, literary theorists, and other political experts have raised similar questions, connecting the scapegoating of disenfranchised populations to white superiority.

On July 23, 2019, Christopher A. Wray, the head of the FBI, said at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing that the agency had made around 100 domestic terrorism

arrests since October 1, 2018, and that the majority of them were

connected in some way with white supremacy. Wray said that the Bureau

was "aggressively pursuing [domestic terrorism] using both

counterterrorism resources and criminal investigative resources and

partnering closely with our state and local partners," but said that it

was focused on the violence itself and not on its ideological basis. A

similar number of arrests had been made for instances of international

terrorism. In the past, Wray has said that white supremacy was a

significant and "pervasive" threat to the U.S.

On September 20, 2019, the acting Secretary of Homeland Security, Kevin McAleenan,

announced his department's revised strategy for counter-terrorism,

which included a new emphasis on the dangers inherent in the white

supremacy movement. McAleenan called white supremacy one of the most

"potent ideologies" behind domestic terrorism-related violent acts. In a

speech at the Brookings Institution,

McAleenan cited a series of high-profile shooting incidents, and said

"In our modern age, the continued menace of racially based violent

extremism, particularly white supremacist extremism, is an abhorrent

affront to the nation, the struggle and unity of its diverse

population." The new strategy will include better tracking and analysis

of threats, sharing information with local officials, training local law

enforcement on how to deal with shooting events, discouraging the

hosting of hate sites online, and encouraging counter-messages.

Effect of the media

White supremacism has been depicted in music videos, feature films, documentaries, journal entries, and on social media. The 1915 silent drama film The Birth of a Nation followed the rising racial, economic, political, and geographic tensions leading up to the Emancipation Proclamation and the Southern Reconstruction era that was the genesis of the Ku Klux Klan.

David Duke, a former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, believed that the Internet was going to create a "chain reaction of racial enlightenment that will shake the world." Jessie Daniels, of CUNY-Hunter College, also said that racist groups see the Internet as a way to spread their ideologies, influence others and gain supporters. Legal scholar Richard Hasen describes a "dark side" of social media:

There certainly were hate groups before the Internet and social media. [But with social media] it just becomes easier to organize, to spread the word, for people to know where to go. It could be to raise money, or it could be to engage in attacks on social media. Some of the activity is virtual. Some of it is in a physical place. Social media has lowered the collective-action problems that individuals who might want to be in a hate group would face. You can see that there are people out there like you. That's the dark side of social media.

With the emergence of Twitter in 2006, and platforms such as Stormfront which was launched in 1996, an alt-right

portal for white supremacists with similar beliefs, both adults and

children, was provided in which they were given a way to connect.

Daniels discussed the emergence of other social media outlets such as 4chan and Reddit, which meant that the "spread of white nationalist symbols and ideas could be accelerated and amplified". Sociologist Kathleen Blee

notes that the anonymity which the Internet provides can make it

difficult to track the extent of white supremacist activity in the

country, but nevertheless she and other experts see an increase in the amount of hate crimes

and white supremacist violence. In the latest wave of white supremacy,

in the age of the Internet, Blee sees the movement as having primarily

become a virtual one, in which divisions between groups become blurred:

"[A]ll these various groups that get jumbled together as the alt-right

and people who have come in from the more traditional neo-Nazi world.

We're in a very different world now."

A series on YouTube hosted by the grandson of Thomas Robb,

the national director of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, "presents the

Klan's ideology in a format aimed at kids — more specifically, white

kids."[33] The short episodes inveigh against race-mixing, and extol other white supremacist ideologies. A short documentary published by TRT

describes the experience of Imran Garda, a journalist of Indian

descent, who met with Thomas Robb and a traditional KKK group. A sign

that greets people who enter the town states "Diversity is a code for white genocide."

The KKK group interviewed in the documentary summarizes its ideals,

principles, and beliefs, which are emblematic of white supremacists in

the United States. The comic book super hero Captain America, in an ironic co-optation, has been used for dog whistle politics by the alt-right in college campus recruitment in 2017.

British Commonwealth

In 1937, Winston Churchill told the Palestine Royal Commission: "I do not admit for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America or the black people of Australia.

I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact

that a stronger race, a higher-grade race, a more worldly wise race to

put it that way, has come in and taken their place." British historian Richard Toye, author of Churchill's Empire, said that "Churchill did think that white people were superior."

South Africa

A number of Southern African nations experienced severe racial tension and conflict during global decolonization, particularly as white Africans of European ancestry

fought to protect their preferential social and political status.

Racial segregation in South Africa began in colonial times under the Dutch Empire, and it continued when the British took over the Cape of Good Hope in 1795. Apartheid was introduced as an officially structured policy by the Afrikaner-dominated National Party after the general election of 1948.

Apartheid's legislation divided inhabitants into four racial

groups—"black", "white", "coloured", and "Indian", with coloured divided

into several sub-classifications. In 1970, the Afrikaner-run government abolished non-white political representation, and starting that year black people were deprived of South African citizenship. South Africa abolished apartheid in 1991.

Rhodesia

In Rhodesia a predominantly white government issued its own unilateral declaration of independence from the United Kingdom during an unsuccessful attempt to avoid immediate majority rule. Following the Rhodesian Bush War which was fought by African nationalists, Rhodesian prime minister Ian Smith acceded to biracial political representation in 1978 and the state achieved recognition from the United Kingdom as Zimbabwe in 1980.

Poster of the Nazi paper Der Stürmer (1935) condemning relations between Jews and non-Jewish Germans

Germany

Nazism promoted the idea of a superior Germanic people or Aryan race in Germany

during the early 20th century. Notions of white supremacy and Aryan

racial superiority were combined in the 19th century, with white

supremacists maintaining the belief that white people were members of an

Aryan "master race" which was superior to other races, particularly the Jews, who were described as the "Semitic race", Slavs, and Gypsies, which they associated with "cultural sterility". Arthur de Gobineau, a French racial theorist and aristocrat, blamed the fall of the ancien régime

in France on racial degeneracy caused by racial intermixing, which he

argued had destroyed the "purity" of the Nordic or Germanic race.

Gobineau's theories, which attracted a strong following in Germany,

emphasized the existence of an irreconcilable polarity between Aryan or

Germanic peoples and Jewish culture.

As the Nazi Party's chief racial theorist, Alfred Rosenberg oversaw the construction of a human racial "ladder" that justified Hitler's racial and ethnic policies. Rosenberg promoted the Nordic theory, which regarded Nordics as the "master race", superior to all others, including other Aryans (Indo-Europeans). Rosenberg got the racial term Untermensch from the title of Klansman Lothrop Stoddard's 1922 book The Revolt Against Civilization: The Menace of the Under-man. It was later adopted by the Nazis from that book's German version Der Kulturumsturz: Die Drohung des Untermenschen (1925). Rosenberg was the leading Nazi who attributed the concept of the East-European "under man" to Stoddard.

An advocate of the U.S. immigration laws that favored Northern

Europeans, Stoddard wrote primarily on the alleged dangers posed by "colored" peoples to white civilization, and wrote The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy

in 1920. In establishing a restrictive entry system for Germany in

1925, Hitler wrote of his admiration for America's immigration laws:

"The American Union categorically refuses the immigration of physically

unhealthy elements, and simply excludes the immigration of certain

races."

German praise for America's institutional racism, previously found in Hitler's Mein Kampf, was continuous throughout the early 1930s, and Nazi lawyers were advocates of the use of American models. Race-based U.S. citizenship and anti-miscegenation laws directly inspired the Nazis' two principal Nuremberg racial laws—the Citizenship Law and the Blood Law. In order to preserve the Aryan or Nordic race,

the Nazis introduced the Nuremberg Laws in 1935, which forbade sexual

relations and marriages between Germans and Jews, and later between

Germans and Romani and Slavs. The Nazis used the Mendelian inheritance

theory to argue that social traits were innate, claiming that there was

a racial nature associated with certain general traits such as

inventiveness or criminal behavior.

According to the 2012 annual report of Germany's interior intelligence service, the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, at the time there were 26,000 right-wing extremists living in Germany, including 6000 neo-Nazis.

Russia

Neo-Nazi

organisations embracing white supremacist ideology are present in many

countries of the world. In 2007, it was claimed that Russian neo-Nazis

accounted for "half of the world's total".

Ukraine

In June 2015, Democratic Representative John Conyers and his Republican colleague Ted Yoho offered bipartisan amendments to block the U.S. military training of Ukraine's Azov Battalion — called a "neo-Nazi paramilitary militia" by Conyers and Yoho. Some members of the battalion are openly white supremacists.

Academic use of the term

The term white supremacy is used in some academic studies of racial power to denote a system of structural or societal racism

which privileges white people over others, regardless of the presence

or the absence of racial hatred. White racial advantages occur at both a

collective and an individual level (ceteris paribus, i. e.,

when individuals are compared that do not relevantly differ except in

ethnicity). Legal scholar Frances Lee Ansley explains this definition as

follows:

By "white supremacy" I do not mean to allude only to the self-conscious racism of white supremacist hate groups. I refer instead to a political, economic and cultural system in which whites overwhelmingly control power and material resources, conscious and unconscious ideas of white superiority and entitlement are widespread, and relations of white dominance and non-white subordination are daily reenacted across a broad array of institutions and social settings.

This and similar definitions have been adopted or proposed by Charles W. Mills, bell hooks, David Gillborn, Jessie Daniels, and Neely Fuller Jr, and they are widely used in critical race theory and intersectional feminism. Some anti-racist

educators, such as Betita Martinez and the Challenging White Supremacy

workshop, also use the term in this way. The term expresses historic

continuities between a pre–civil rights movement

era of open white supremacism and the current racial power structure of

the United States. It also expresses the visceral impact of structural

racism through "provocative and brutal" language that characterizes

racism as "nefarious, global, systemic, and constant". Academic users of the term sometimes prefer it to racism because it allows for a distinction to be drawn between racist feelings and white racial advantage or privilege.

The term's recent rise in popularity among leftist activists has been characterized by some as counterproductive. John McWhorter,

a specialist in language and race relations, has described its use as

straying from its commonly accepted meaning to encompass less extreme

issues, thereby cheapening the term and potentially derailing productive

discussion. Political columnist Kevin Drum attributes the term's growing popularity to frequent use by Ta-Nehisi Coates,

describing it as a "terrible fad" which fails to convey nuance. He

claims that the term should be reserved for those who are trying to

promote the idea that whites are inherently superior to blacks and not

used to characterize less blatantly racist beliefs or actions.

The use of the academic definition of white supremacy has been

criticized by Conor Friedersdorf for the confusion it creates for the

general public inasmuch as it differs from the more common dictionary

definition; he argues that it is likely to alienate those it hopes to

convince.

Ideologies and movements

Supporters of Nordicism consider the "Nordic peoples" to be a superior race. By the early 19th century, white supremacy was attached to emerging theories of racial hierarchy. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer attributed cultural primacy to the white race:

The highest civilization and culture, apart from the ancient Hindus and Egyptians, are found exclusively among the white races; and even with many dark peoples, the ruling caste or race is fairer in colour than the rest and has, therefore, evidently immigrated, for example, the Brahmans, the Incas, and the rulers of the South Sea Islands. All this is due to the fact that necessity is the mother of invention because those tribes that emigrated early to the north, and there gradually became white, had to develop all their intellectual powers and invent and perfect all the arts in their struggle with need, want and misery, which in their many forms were brought about by the climate.

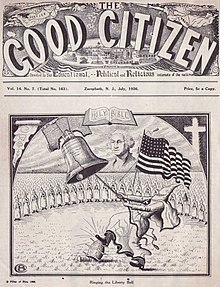

The Good Citizen 1926, published by Pillar of Fire Church

The eugenicist Madison Grant argued in his 1916 book, The Passing of the Great Race, that the Nordic race had been responsible for most of humanity's great achievements, and that admixture was "race suicide".

In this book, Europeans who are not of Germanic origin but have Nordic

characteristics such as blonde/red hair and blue/green/gray eyes, were

considered to be a Nordic admixture and suitable for Aryanization.

Members of the second Ku Klux Klan at a rally in 1923.

In the United States, the Ku Klux Klan

(KKK) is the group most associated with the white supremacist movement.

Many white supremacist groups are based on the concept of preserving

genetic purity, and do not focus solely on discrimination based on skin color. The KKK's reasons for supporting racial segregation are not primarily based on religious ideals, but some Klan groups are openly Protestant. The KKK and other white supremacist groups like Aryan Nations, The Order and the White Patriot Party are considered antisemitic.

Nazi Germany promulgated white supremacy based on the belief that the Aryan race, or the Germans, were the master race. It was combined with a eugenics programme that aimed for racial hygiene through compulsory sterilization of sick individuals and extermination of Untermenschen ("subhumans"): Slavs, Jews and Romani, which eventually culminated in the Holocaust.

Christian Identity is another movement closely tied to white supremacy. Some white supremacists identify themselves as Odinists, although many Odinists reject white supremacy. Some white supremacist groups, such as the South African Boeremag, conflate elements of Christianity and Odinism. Creativity (formerly known as "The World Church of the Creator") is atheistic and it denounces Christianity and other theistic religions. Aside from this, its ideology is similar to that of many Christian Identity groups because it believes in the antisemitic conspiracy theory that there is a "Jewish conspiracy" in control of governments, the banking industry and the media. Matthew F. Hale,

founder of the World Church of the Creator, has published articles

stating that all races other than white are "mud races", which is what

the group's religion teaches.

The white supremacist ideology has become associated with a racist faction of the skinhead subculture, despite the fact that when the skinhead culture first developed in the United Kingdom in the late 1960s, it was heavily influenced by black fashions and music, especially Jamaican reggae and ska, and African American soul music.

White supremacist recruitment activities are primarily conducted at a grassroots level as well as on the Internet. Widespread access to the Internet has led to a dramatic increase in white supremacist websites. The Internet provides a venue to openly express white supremacist ideas at little social cost, because people who post the information are able to remain anonymous.

White separatism

White separatism is a political and social movement that seeks the separation of white people from people of other races and ethnicities, the establishment of a white ethnostate by removing non-whites from existing communities or by forming new communities elsewhere.

Most modern researchers do not view white separatism as distinct from white supremacist beliefs. The Anti-Defamation League defines white separatism as "a form of white supremacy"; the Southern Poverty Law Center defines both white nationalism and white separatism as "ideologies based on white supremacy." Facebook has banned content that is openly white nationalist

or white separatist because "white nationalism and white separatism

cannot be meaningfully separated from white supremacy and organized hate

groups".

Use of the term to self-identify has been criticized as a

dishonest rhetorical ploy. The Anti-Defamation League argues that white

supremacists use the phrase because they believe it has fewer negative

connotations than the term white supremacist.

Dobratz & Shanks-Meile reported that adherents usually reject marriage "outside the white race". They argued the existence of "a distinction between the white supremacist's desire to dominate (as in apartheid, slavery, or segregation) and complete separation by race".

They argued that this is a matter of pragmatism, that while many white

supremacists are also white separatists, contemporary white separatists

reject the view that returning to a system of segregation is possible or

desirable in the United States.