| Tibeto-Burman | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Southeast Asia, East Asia, South Asia |

| Linguistic classification | Sino-Tibetan

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Tibeto-Burman |

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-5 | tbq |

| Glottolog | None |

| |

The Tibeto-Burman languages are the non-Sinitic members of the Sino-Tibetan language family, over 400 of which are spoken throughout the highlands of Southeast Asia as well as certain parts of East Asia and South Asia. Around 60 million people speak Tibeto-Burman languages, around half of whom speak Burmese, and 13% of whom speak Tibetic languages. The name derives from the most widely spoken of these languages, namely Burmese (over 35 million speakers) and the Tibetic languages (over 8 million). These languages also have extensive literary traditions, dating from the 12th and 7th centuries respectively. Most of the other languages are spoken by much smaller communities, and many of them have not been described in detail.

Some taxonomies divide Sino-Tibetan into Sinitic and Tibeto-Burman branches (e.g. Benedict, Matisoff), but other scholars deny that Tibeto-Burman comprises a monophyletic group.

History

During

the 18th century, several scholars noticed parallels between Tibetan

and Burmese, both languages with extensive literary traditions.

In the following century, Brian Houghton Hodgson

collected a wealth of data on the non-literary languages of the

Himalayas and northeast India, noting that many of these were related to

Tibetan and Burmese.

Others identified related languages in the highlands of Southeast Asia and south-west China.

The name "Tibeto-Burman" was first applied to this group in 1856 by James Logan, who added Karen in 1858.

Charles Forbes viewed the family as uniting the Gangetic and Lohitic branches of Max Müller's Turanian, a huge family consisting of all the Eurasian languages except the Semitic, "Aryan" (Indo-European) and Chinese languages.

The third volume of the Linguistic Survey of India was devoted to the Tibeto-Burman languages of British India.

Julius Klaproth had noted in 1823 that Burmese, Tibetan and Chinese all shared common basic vocabulary, but that Thai, Mon and Vietnamese were quite different.

Several authors, including Ernst Kuhn in 1883 and August Conrady in 1896, described an "Indo-Chinese" family consisting of two branches, Tibeto-Burman and Chinese-Siamese.

The Tai languages were included on the basis of vocabulary and typological features shared with Chinese.

Jean Przyluski introduced the term sino-tibétain (Sino-Tibetan) as the title of his chapter on the group in Antoine Meillet and Marcel Cohen's Les Langues du Monde in 1924.

The Tai languages have not been included in most Western accounts

of Sino-Tibetan since the Second World War, though many Chinese

linguists still include them.

The link between Tibeto-Burman and Chinese is now accepted by most

linguists, with a few exceptions such as Roy Andrew Miller and Christopher Beckwith.

More recent controversy has centred on the proposed primary branching of Sino-Tibetan into Chinese and Tibeto-Burman subgroups.

In spite of the popularity of this classification, first proposed by Kuhn and Conrady, and also promoted by Paul Benedict (1972) and later James Matisoff, Tibeto-Burman has not been demonstrated to be a valid family in its own right.

Overview

Most

of the Tibeto-Burman languages are spoken in remote mountain areas,

which has hampered their study. Many lack a written standard.

It is generally easier to identify a language as Tibeto-Burman than to

determine its precise relationship with other languages of the group.

The subgroupings that have been established with certainty number

several dozens, ranging from well-studied groups of dozens of languages

with millions of speakers to several isolates, some only newly discovered but in danger of extinction.

These subgroups are here surveyed on a geographical basis.

Southeast Asia and southwest China

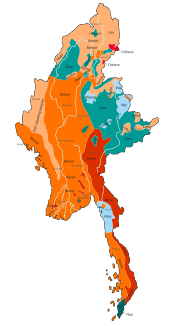

Language families of Myanmar

The southernmost group is the Karen languages,

spoken by three million people on both sides of the Burma–Thailand

border. They differ from all other Tibeto-Burman languages (except Bai)

in having a subject–verb–object word order, attributed to contact with Tai–Kadai and Austroasiatic languages.

The most widely spoken Tibeto-Burman language is Burmese,

the national language of Myanmar, with over 32 million speakers and a

literary tradition dating from the early 12th century. It is one of the Lolo-Burmese languages,

an intensively studied and well-defined group comprising approximately

100 languages spoken in Myanmar and the highlands of Thailand, Laos,

Vietnam, and Southwest China. Major languages include the Loloish languages, with two million speakers in western Sichuan and northern Yunnan, the Akha language and Hani languages, with two million speakers in southern Yunnan, eastern Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam, and Lisu and Lahu

in Yunnan, northern Myanmar and northern Thailand. All languages of the

Loloish subgroup show significant Austroasiatic influence. The Pai-lang

songs, transcribed in Chinese characters in the 1st century, appear to

record words from a Lolo-Burmese language, but arranged in Chinese

order.

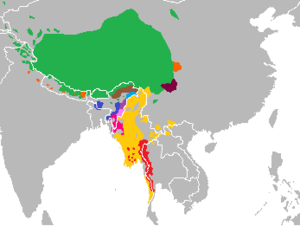

Language families of China, with Tibeto-Burman in orange

The Tibeto-Burman languages of south-west China have been heavily

influenced by Chinese over a long period, leaving their affiliations

difficult to determine. The grouping of the Bai language,

with one million speakers in Yunnan, is particularly controversial,

with some workers suggesting that it is a sister language to Chinese.

The Naxi language of northern Yunnan is usually included in Lolo-Burmese, though other scholars prefer to leave it unclassified. The hills of northwestern Sichuan are home to the small Qiangic and Rgyalrongic groups of languages, which preserve many archaic features. The most easterly Tibeto-Burman language is Tujia, spoken in the Wuling Mountains on the borders of Hunan, Hubei, Guizhou and Chongqing.

Two historical languages are believed to be Tibeto-Burman, but their precise affiliation is uncertain. The Pyu language of central Myanmar in the first centuries is known from inscriptions using a variant of the Gupta script. The Tangut language of the 12th century Western Xia of northern China is preserved in numerous texts written in the Chinese-inspired Tangut script.

Tibet and South Asia

Language families of South Asia, with Tibeto-Burman in orange

Over eight million people in the Tibetan Plateau and neighbouring areas in Baltistan, Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan speak one of several related Tibetic languages. There is an extensive literature in Classical Tibetan dating from the 8th century. The Tibetic languages are usually grouped with the smaller East Bodish languages of Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh as the Bodish group.

Many diverse Tibeto-Burman languages are spoken on the southern slopes of the Himalayas.

Sizable groups that have been identified are the West Himalayish languages of Himachal Pradesh and western Nepal, the Tamangic languages of western Nepal, including Tamang with one million speakers, and the Kiranti languages of eastern Nepal.

The remaining groups are small, with several isolates.

The Newar language

(Nepal Bhasa) of central Nepal has a million speakers and literature

dating from the 12th century, and nearly a million people speak Magaric languages, but the rest have small speech communities.

Other isolates and small groups in Nepal are Dura, Raji–Raute, Chepangic and Dhimalish.

Lepcha is spoken in an area from eastern Nepal to western Bhutan.

Most of the languages of Bhutan are Bodish, but it also has three small isolates, 'Ole ("Black Mountain Monpa"), Lhokpu and Gongduk and a larger community of speakers of Tshangla.

The Tani languages include most of the Tibeto-Burman languages of Arunachal Pradesh and adjacent areas of Tibet.

The remaining languages of Arunachal Pradesh are much more diverse, belonging to the small Siangic, Kho-Bwa (or Kamengic), Hruso, Miju and Digaro languages (or Mishmic) groups.

These groups have relatively little Tibeto-Burman vocabulary, and Bench and Post dispute their inclusion in Sino-Tibetan.

Northeastern states of India (most of Arunachal Pradesh and the northern part of Assam are also claimed by China)

The greatest variety of languages and subgroups is found in the highlands stretching from northern Myanmar to northeast India.

Northern Myanmar is home to the small Nungish group, as well as the Jingpho–Luish languages, including Jingpho with nearly a million speakers.

The Brahmaputran or Sal languages include at least the Bodo–Garo and Konyak languages, spoken in an area stretching from northern Myanmar through the Indian states of Nagaland, Meghalaya, and Tripura, and are often considered to include the Jingpho–Luish group.

The border highlands of Nagaland, Manipur and western Myanmar are home to the small Ao, Angami–Pochuri, Tangkhulic, and Zeme groups of languages, as well as the Karbi language.

Meithei, the main language of Manipur with 1.4 million speakers, is sometimes linked with the 50 or so Kuki-Chin languages are spoken in Mizoram and the Chin State of Myanmar.

The Mru language is spoken by a small group in the Chittagong Hill Tracts between Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Classification

There have been two milestones in the classification of Sino-Tibetan and Tibeto-Burman languages, Shafer (1955) and Benedict (1972), which were actually produced in the 1930s and 1940s respectively.

Shafer (1955)

Shafer's

tentative classification took an agnostic position and did not

recognize Tibeto-Burman, but placed Chinese (Sinitic) on the same level

as the other branches of a Sino-Tibetan family.

He retained Tai–Kadai (Daic) within the family, allegedly at the

insistence of colleagues, despite his personal belief that they were not

related.

Benedict (1972)

A very influential, although also tentative, classification is that of Benedict (1972),

which was actually written around 1941. Like Shafer's work, this drew

on the data assembled by the Sino-Tibetan Philology Project, which was

directed by Shafer and Benedict in turn. Benedict envisaged Chinese as

the first family to branch off, followed by Karen.

- Sino-Tibetan

- Chinese

- Tibeto-Karen

- Karen

- Tibeto-Burman

The Tibeto-Burman family is then divided into seven primary branches:

I. Tibetan–Kanauri (a.k.a. Bodish–Himalayish)

- A. Bodish

- (Tibetic, Gyarung, Takpa, Tsangla, Murmi & Gurung)

- B. Himalayish

- i. "major" Himalayish

- ii. "minor" Himalayish

- (Rangkas, Darmiya, Chaudangsi, Byangsi)

- (perhaps also Dzorgai, Lepcha, Magari)

II. Bahing–Vayu

- A. Bahing (Sunuwar, Khaling)

- B. Khambu (Sampang, Rungchenbung, Yakha, and Limbu)

- C. Vayu–Chepang

- (perhaps also Newar)

III. Abor–Miri–Dafla

IV. Kachin

- (perhaps including Luish)

V. Burmese–Lolo

- A. Burmese–Maru

- B. Southern Lolo

- C. Northern Lolo

- D. Kanburi Lawa

- E. Moso

- F. Hsi-fan (Qiangic and Jiarongic languages apart from Qiang and Gyarung themselves)

- G. Tangut

- (perhaps also Nung)

VI. Bodo-Garo

- A. Bodo

- B. Garo (A·chik)

- C. Borok (Tripuri (Tøipra))

- D. Dimasa

- E. Mech

- F. Rava (Koch)

- G. Tiwa (Lalung)

- H. Sutiya

- I. Saraniya

- J. Sonowal

- (Perhaps also "Naked Naga" a.k.a. Konyak)

VII. Kuki–Naga (a.k.a. Kukish)

Matisoff (1978)

James Matisoff proposes a modification of Benedict that demoted Karen but kept the divergent position of Sinitic. Of the 7 branches within Tibeto-Burman, 2 branches (Baic and Karenic) have SVO-order languages, whereas all the other 5 branches have SOV-order languages.

- Sino-Tibetan

- Chinese

- Tibeto-Burman

Tibeto-Burman is then divided into several branches, some of them geographic conveniences rather than linguistic proposals:

- Kamarupan (geographic)

- Kuki-Chin–Naga (geographic)

- Abor–Miri–Dafla

- Bodo–Garo

- Himalayish (geographic)

- Mahakiranti (includes Newar, Magar, Kiranti)

- Tibeto-Kanauri (includes Lepcha)

- Qiangic

- Jingpho–Nungish–Luish

- Lolo–Burmese–Naxi

- Karenic

- Baic

- Tujia (unclassified)

Matisoff makes no claim that the families in the Kamarupan or

Himalayish branches have a special relationship to one another other

than a geographic one. They are intended rather as categories of

convenience pending more detailed comparative work.

Matisoff also notes that Jingpho–Nungish–Luish is central to the

family in that it contains features of many of the other branches, and

is also located around the center of the Tibeto-Burman-speaking area.

Bradley (2002)

Since

Benedict (1972), many languages previously inadequately documented have

received more attention with the publication of new grammars,

dictionaries, and wordlists. This new research has greatly benefited

comparative work, and Bradley (2002) incorporates much of the newer data.

I. Western (= Bodic)

- A. Tibetan–Kanauri

- i. Tibetic

- ii. Gurung

- iii. East Bodic (incl. Tsangla)

- iv. Kanauri

- B. Himalayan

II. Sal

- A. Baric (Bodo–Garo–Northern Naga)

- B. Jinghpaw

- C. Luish (incl. Pyu)

- D. Kuki-Chin (incl. Meithei and Karbi)

III. Central (perhaps a residual group, not actually related to each other. Lepcha may also fit here.)

- A. Adi–Galo–Mishing–Nishi

- B. Mishmi (Digarish and Keman)

- C. Rawang

IV. North-Eastern

V. South-Eastern

- A. Burmese–Lolo (incl. Mru)

- B. Karen

van Driem

George van Driem rejects the primary split of Sinitic, making Tibeto-Burman synonymous with Sino-Tibetan.

Matisoff (2015)

The internal structure of Tibeto-Burman is tentatively classified as follows by Matisoff (2015: xxxii, 1123-1127) in the final release of the Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus (STEDT).

- Northeast Indian areal group

- “North Assam”

- Kuki-Chin

- "Naga" areal group

- Central Naga (Ao group)

- Angami–Pochuri group

- Zeme group

- Tangkhulic

- Meithei

- Mikir / Karbi

- Mru

- Sal

- Bodo–Garo

- Northern Naga / Konyakian

- Jingpho–Asakian

- Himalayish

- Tangut-Qiang

- Nungic

- Tujia

- Lolo-Burmese–Naxi

- Karenic

- Bai

Other languages

The classification of Tujia is difficult due to extensive borrowing. Other unclassified Tibeto-Burman languages include Basum and the recently described Lamo

language. New Tibeto-Burman languages continue to be recognized, some

not closely related to other languages. Recently recognized distinct

languages include Koki Naga.

Randy LaPolla (2003) proposed a Rung branch of Tibeto-Burman, based on morphological evidence, but this is not widely accepted.

Scott DeLancey (2015) proposed a Central branch of Tibeto-Burman based on morphological evidence.

Roger Blench and Mark Post (2011) list a number of divergent languages of Arunachal Pradesh, in northeastern India, that might have non-Tibeto-Burman substrates, or could even be non-Tibeto-Burman language isolates:

- Kamengic

- [Northern] Mishmi (Digarish)

- Siangic

- Puroik (Sulung) - East Kameng District

- Hruso (Aka) - Thrizino Circle, West Kameng District

- Miji (Sajolang, Dimai, Dhimmai)

- Miju

Blench and Post believe the remaining languages with these substratal characteristics are more clearly Sino-Tibetan:

- East Bodish

- Meyor (Zakhring)

- Monpa of Tawang - Tawang District

- Monpa of Kalaktang (Tshangla)

- Monpa of Zemithang

- Monpa of Mago-Thingbu

- Tani: Nah