A back-to-the-land movement is any of various agrarian movements across different historical periods. The common thread is a call for people to take up smallholding and to grow food from the land with an emphasis on a greater degree of self-sufficiency, autonomy, and local community

than found in a prevailing industrial or postindustrial way of life.

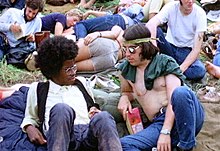

There have been a variety of motives behind such movements, such as social reform, land reform, and civilian war efforts. Groups involved have included political reformers, counterculture hippies, and religious separatists.

The concept was popularized in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century by activist Bolton Hall, who set up vacant lot farming in New York City and wrote many books on the subject. The practice, however, was strong in Europe even before that time.

During World War II, when Great Britain faced a blockade by Nazi U-boats, a "Dig for Victory"

campaign urged civilians to fight food shortages by growing vegetables

on any available patch of land. In the USA between the mid-1960s and

mid-1970s there was a revived back-to-the-land movement, with

substantial numbers migrating from cities to rural areas.

The back-to-the-land movement has ideological links to distributism, a 1920s and 1930s attempt to find a "Third Way" between capitalism and socialism.

The movement throughout history

The American social commentator and poet Gary Snyder

has related that there have been back-to-the-land population movements

throughout the centuries, and throughout the world, largely due to the

occurrence of severe urban problems and people's felt need to live a

better life, often simply to survive.

The historian and philosopher of urbanism Jane Jacobs remarked in an interview with Stewart Brand that with the Fall of Rome city dwellers re-inhabited the rural areas of the region.

From another point of departure, Yi-Fu Tuan

takes a view that such trends have often been privileged and motivated

by sentiment. "Awareness of the past is an important element in the love

of place," he writes, in his 1974 book Topophilia. Tuan writes

that an appreciation of nature springs from wealth, privilege, and the

antithetical values of cities. He argues that literature about land

(and, subsequently, about going back to the land) is largely

sentimental; "little," he writes, "is known about the farmer's attitudes

to nature..." Tuan finds historical instances of the desire of the

civilized to escape civilization in the Hellenistic, Roman, Augustan, and Romantic eras, and, from one of the earliest recorded myths, the Epic of Gilgamesh.

The movement in North America

Regarding

North America, many individuals and households have moved from urban or

suburban circumstances to rural ones at different times; for instance,

the economic theorist and land-based American experimenter Ralph Borsodi (author of Flight from the City) is said to have influenced thousands of urban-living people to try a modern homesteading life during the Great Depression. The New Deal town of Arthurdale, West Virginia was built in 1933 using the back-to-the-land ideas current at the time.

There was again a fair degree of interest in moving to rural land after World War II. In 1947, Betty MacDonald published what became a popular book, The Egg and I, telling her story of marrying and then moving to a small farm on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington state. This story was the basis of a successful comedy film starring Claudette Colbert and Fred MacMurray.

The Canadian writer Farley Mowat says that many returned veterans after World War II sought a meaningful life far from the ignobility of modern warfare, regarding his own experience as typical of the pattern. In Canada, those who sought a life completely outside of the cities, suburbs, and towns frequently moved into semi-wilderness environs.

But what made the later phenomenon of the 1960s and 1970s

especially significant was that the rural-relocation trend was sizable

enough that it was identified in the American demographic statistics.

Roots of this movement can perhaps be traced to some of Bradford Angier's books, such as At Home in the Woods (1951) and We Like it Wild (1963), Louise Dickinson Rich's We Took to the Woods (1942) and subsequent books, or perhaps even more compellingly to the 1954 publication of Helen and Scott Nearing's book, Living the Good Life. This book chronicles the Nearings' move to an older house in a rural area of Vermont and their self-sufficient and simple lifestyle.

In their initial move, the Nearings were driven by the circumstances of

the Great Depression and influenced by earlier writers, particularly Henry David Thoreau. Their book was published six years after A Sand County Almanac, by the ecologist and environmental activist Aldo Leopold,

was published, in 1948. Influences aside, the Nearings had planned and

worked hard, developing their homestead and life according to a

twelve-point plan they had drafted.

The narrative of Phil Cousineau's documentary film Ecological Design: Inventing the Future asserts that in the decades after World War II,

"The world was forced to confront the dark shadow of science and

industry... There was a clarion call for a return to a life of human

scale." By the late 1960s, many people had recognized that, leaving

their city or suburban lives, they completely lacked any familiarity

with such basics of life as food sources (for instance, what a potato

plant looks like, or the act of milking a cow) — and they felt out of

touch with nature, in general. While the back-to-the-land movement was

not strictly part of the counterculture of the 1960s, the two movements had some overlap in participation.

Many people were attracted to getting more in touch with the

basics just mentioned, but the movement could also have been fueled by

the negatives of modern life: rampant consumerism, the failings of government and society, including the Vietnam War, and a perceived general urban deterioration, including a growing public concern about air and water pollution. Events such as the Watergate scandal and the 1973 energy crisis

contributed to these views. Some people rejected the struggle and

boredom of "moving up the company ladder." Paralleling the desire for

reconnection with nature was a desire to reconnect with physical work.

Farmer and author Gene Logsdon expressed the aim aptly as: "the kind of

independence that defines success in terms of how much food, clothing,

shelter, and contentment I could produce for myself rather than how much

I could buy."

There was also a segment within the movement who already had a

familiarity with rural life and farming, who already had skills, and who

wanted land of their own on which they could demonstrate that organic farming could be made practical and economically successful.

Besides the Nearings and other authors writing later along

similar lines, another influence from the world of American publishing

was the unprecedented, vigorous, and intelligent Whole Earth Catalogs. Stewart Brand

and a circle of friends and family began the effort in 1968, because

Brand believed that there was a groundswell of biologists, designers,

engineers, sociologists, organic farmers, and social experimenters who

wished to transform civilization along lines that might be called "sustainable".

Brand and cohorts created a catalog of "tools" - defined broadly to

include useful books, design aids, maps, gardening implements, carpentry

and masonry tools, metalworking equipment, and a great deal more.

Another important publication was The Mother Earth News, a periodical (originally on newsprint) that was founded a couple years after the Catalog.

Ultimately gaining a large circulation, the magazine was focused on

how-to articles, personal stories of successful and budding

homesteaders, interviews with key thinkers, and the like. The magazine

stated its philosophy was based on returning to people a greater measure

of control of their own lives.

Many of the North American back-to-the-landers of the 1960s and 1970s made use of the Mother Earth News, the Whole Earth Catalogs

and derivative publications. But as time went on, the movement itself

drew more people into it, more or less independently of impetus from the

publishing world.