Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the ontology and nature of the mind and its relationship with the body. The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a number of other issues are addressed, such as the hard problem of consciousness and the nature of particular mental states. Aspects of the mind that are studied include mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness, the ontology of the mind, the nature of thought, and the relationship of the mind to the body.

Dualism and monism are the two central schools of thought on the mind–body problem, although nuanced views have arisen that do not fit one or the other category neatly.

- Dualism finds its entry into Western philosophy thanks to René Descartes in the 17th century. Substance dualists like Descartes argue that the mind is an independently existing substance, whereas property dualists maintain that the mind is a group of independent properties that emerge from and cannot be reduced to the brain, but that it is not a distinct substance.

- Monism is the position that mind and body are ontologically indiscernible entities (not dependent substances). This view was first advocated in Western philosophy by Parmenides in the 5th century BCE and was later espoused by the 17th-century rationalist Baruch Spinoza. Physicalists argue that only entities postulated by physical theory exist, and that mental processes will eventually be explained in terms of these entities as physical theory continues to evolve. Physicalists maintain various positions on the prospects of reducing mental properties to physical properties (many of whom adopt compatible forms of property dualism), and the ontological status of such mental properties remains unclear. Idealists maintain that the mind is all that exists and that the external world is either mental itself, or an illusion created by the mind. Neutral monists such as Ernst Mach and William James argue that events in the world can be thought of as either mental (psychological) or physical depending on the network of relationships into which they enter, and dual-aspect monists such as Spinoza adhere to the position that there is some other, neutral substance, and that both matter and mind are properties of this unknown substance. The most common monisms in the 20th and 21st centuries have all been variations of physicalism; these positions include behaviorism, the type identity theory, anomalous monism and functionalism.

Most modern philosophers of mind adopt either a reductive physicalist or non-reductive physicalist position, maintaining in their different ways that the mind is not something separate from the body. These approaches have been particularly influential in the sciences, especially in the fields of sociobiology, computer science (specifically, artificial intelligence), evolutionary psychology and the various neurosciences. Reductive physicalists assert that all mental states and properties will eventually be explained by scientific accounts of physiological processes and states. Non-reductive physicalists argue that although the mind is not a separate substance, mental properties supervene on physical properties, or that the predicates and vocabulary used in mental descriptions and explanations are indispensable, and cannot be reduced to the language and lower-level explanations of physical science. Continued neuroscientific progress has helped to clarify some of these issues; however, they are far from being resolved. Modern philosophers of mind continue to ask how the subjective qualities and the intentionality of mental states and properties can be explained in naturalistic terms.

However, a number of issues have been recognized with non-reductive physicalism. First, it is irreconcilable with self-identity over time. Secondly, intentional states of consciousness do not make sense on non-reductive physicalism. Thirdly, free will is impossible to reconcile with either reductive or non-reductive physicalism. Fourthly, it fails to properly explain the phenomenon of mental causation.

Mind–body problem

The mind–body problem concerns the explanation of the relationship that exists between minds, or mental processes, and bodily states or processes. The main aim of philosophers working in this area is to determine the nature of the mind and mental states/processes, and how—or even if—minds are affected by and can affect the body.

Perceptual experiences depend on stimuli that arrive at our various sensory organs from the external world, and these stimuli cause changes in our mental states, ultimately causing us to feel a sensation, which may be pleasant or unpleasant. Someone's desire for a slice of pizza, for example, will tend to cause that person to move his or her body in a specific manner and in a specific direction to obtain what he or she wants. The question, then, is how it can be possible for conscious experiences to arise out of a lump of gray matter endowed with nothing but electrochemical properties.

A related problem is how someone's propositional attitudes (e.g. beliefs and desires) cause that individual's neurons to fire and muscles to contract. These comprise some of the puzzles that have confronted epistemologists and philosophers of mind from the time of René Descartes.

Dualist solutions to the mind–body problem

Dualism is a set of views about the relationship between mind and matter (or body). It begins with the claim that mental phenomena are, in some respects, non-physical. One of the earliest known formulations of mind–body dualism was expressed in the eastern Samkhya and Yoga schools of Hindu philosophy (c. 650 BCE), which divided the world into purusha (mind/spirit) and prakriti (material substance). Specifically, the Yoga Sutra of Patanjali presents an analytical approach to the nature of the mind.

In Western Philosophy, the earliest discussions of dualist ideas are in the writings of Plato who suggested that humans' intelligence (a faculty of the mind or soul) could not be identified with, or explained in terms of, their physical body. However, the best-known version of dualism is due to René Descartes (1641), and holds that the mind is a non-extended, non-physical substance, a "res cogitans". Descartes was the first to clearly identify the mind with consciousness and self-awareness, and to distinguish this from the brain, which was the seat of intelligence. He was therefore the first to formulate the mind–body problem in the form in which it still exists today.

Arguments for dualism

The most frequently used argument in favor of dualism appeals to the common-sense intuition that conscious experience is distinct from inanimate matter. If asked what the mind is, the average person would usually respond by identifying it with their self, their personality, their soul, or another related entity. They would almost certainly deny that the mind simply is the brain, or vice versa, finding the idea that there is just one ontological entity at play to be too mechanistic or unintelligible. Modern philosophers of mind think that these intuitions are misleading and that we critical faculties, along with empirical evidence from the sciences, should be used to examine these assumptions and determine whether there is any real basis to them.

The mental and the physical seem to have quite different, and perhaps irreconcilable, properties. Mental events have a subjective quality, whereas physical events do not. So, for example, one can reasonably ask what a burnt finger feels like, or what a blue sky looks like, or what nice music sounds like to a person. But it is meaningless, or at least odd, to ask what a surge in the uptake of glutamate in the dorsolateral portion of the prefrontal cortex feels like.

Philosophers of mind call the subjective aspects of mental events "qualia" or "raw feels". There are qualia involved in these mental events that seem particularly difficult to reduce to anything physical. David Chalmers explains this argument by stating that we could conceivably know all the objective information about something, such as the brain states and wavelengths of light involved with seeing the color red, but still not know something fundamental about the situation – what it is like to see the color red.

If consciousness (the mind) can exist independently of physical reality (the brain), one must explain how physical memories are created concerning consciousness. Dualism must therefore explain how consciousness affects physical reality. One possible explanation is that of a miracle, proposed by Arnold Geulincx and Nicolas Malebranche, where all mind–body interactions require the direct intervention of God.

Another argument that has been proposed by C. S. Lewis is the Argument from Reason: if, as monism implies, all of our thoughts are the effects of physical causes, then we have no reason for assuming that they are also the consequent of a reasonable ground. Knowledge, however, is apprehended by reasoning from ground to consequent. Therefore, if monism is correct, there would be no way of knowing this—or anything else—we could not even suppose it, except by a fluke.

The zombie argument is based on a thought experiment proposed by Todd Moody, and developed by David Chalmers in his book The Conscious Mind. The basic idea is that one can imagine one's body, and therefore conceive the existence of one's body, without any conscious states being associated with this body. Chalmers' argument is that it seems possible that such a being could exist because all that is needed is that all and only the things that the physical sciences describe about a zombie must be true of it. Since none of the concepts involved in these sciences make reference to consciousness or other mental phenomena, and any physical entity can be by definition described scientifically via physics, the move from conceivability to possibility is not such a large one. Others such as Dennett have argued that the notion of a philosophical zombie is an incoherent, or unlikely, concept. It has been argued under physicalism that one must either believe that anyone including oneself might be a zombie, or that no one can be a zombie—following from the assertion that one's own conviction about being (or not being) a zombie is a product of the physical world and is therefore no different from anyone else's. This argument has been expressed by Dennett who argues that "Zombies think they are conscious, think they have qualia, think they suffer pains—they are just 'wrong' (according to this lamentable tradition) in ways that neither they nor we could ever discover!"

Interactionist dualism

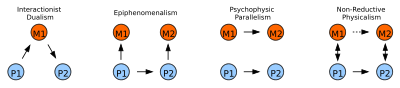

Interactionist dualism, or simply interactionism, is the particular form of dualism first espoused by Descartes in the Meditations. In the 20th century, its major defenders have been Karl Popper and John Carew Eccles. It is the view that mental states, such as beliefs and desires, causally interact with physical states.

Descartes' argument for this position can be summarized as follows: Seth has a clear and distinct idea of his mind as a thinking thing that has no spatial extension (i.e., it cannot be measured in terms of length, weight, height, and so on). He also has a clear and distinct idea of his body as something that is spatially extended, subject to quantification and not able to think. It follows that mind and body are not identical because they have radically different properties.

Seth's mental states (desires, beliefs, etc.) have causal effects on his body and vice versa: A child touches a hot stove (physical event) which causes pain (mental event) and makes her yell (physical event), this in turn provokes a sense of fear and protectiveness in the caregiver (mental event), and so on.

Descartes' argument depends on the premise that what Seth believes to be "clear and distinct" ideas in his mind are necessarily true. Many contemporary philosophers doubt this. For example, Joseph Agassi suggests that several scientific discoveries made since the early 20th century have undermined the idea of privileged access to one's own ideas. Freud claimed that a psychologically-trained observer can understand a person's unconscious motivations better than the person himself does. Duhem has shown that a philosopher of science can know a person's methods of discovery better than that person herself does, while Malinowski has shown that an anthropologist can know a person's customs and habits better than the person whose customs and habits they are. He also asserts that modern psychological experiments that cause people to see things that are not there provide grounds for rejecting Descartes' argument, because scientists can describe a person's perceptions better than the person herself can.

Other forms of dualism

Psychophysical parallelism

Psychophysical parallelism, or simply parallelism, is the view that mind and body, while having distinct ontological statuses, do not causally influence one another. Instead, they run along parallel paths (mind events causally interact with mind events and brain events causally interact with brain events) and only seem to influence each other. This view was most prominently defended by Gottfried Leibniz. Although Leibniz was an ontological monist who believed that only one type of substance, the monad, exists in the universe, and that everything is reducible to it, he nonetheless maintained that there was an important distinction between "the mental" and "the physical" in terms of causation. He held that God had arranged things in advance so that minds and bodies would be in harmony with each other. This is known as the doctrine of pre-established harmony.

Occasionalism

Occasionalism is the view espoused by Nicholas Malebranche as well as Islamic philosophers such as Abu Hamid Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Ghazali that asserts that all supposedly causal relations between physical events, or between physical and mental events, are not really causal at all. While body and mind are different substances, causes (whether mental or physical) are related to their effects by an act of God's intervention on each specific occasion.

Property dualism

Property dualism is the view that the world is constituted of one kind of substance – the physical kind – and there exist two distinct kinds of properties: physical properties and mental properties. It is the view that non-physical, mental properties (such as beliefs, desires and emotions) inhere in some physical bodies (at least, brains). Sub-varieties of property dualism include:

- Emergent materialism asserts that when matter is organized in the appropriate way (i.e. in the way that living human bodies are organized), mental properties emerge in a way not fully accountable for by physical laws. These emergent properties have an independent ontological status and cannot be reduced to, or explained in terms of, the physical substrate from which they emerge. They are dependent on the physical properties from which they emerge, but opinions vary as to the coherence of top–down causation, i.e. the causal effectiveness of such properties. A form of emergent materialism has been espoused by David Chalmers and the concept has undergone something of a renaissance in recent years, but it was already suggested in the 19th century by William James.

- Epiphenomenalism is a doctrine first formulated by Thomas Henry Huxley. It consists of the view that mental phenomena are causally ineffectual, where one or more mental states do not have any influence on physical states or mental phenomena are the effects, but not the causes, of physical phenomena. Physical events can cause other physical and mental events, but mental events cannot cause anything since they are just causally inert by-products (i.e. epiphenomena) of the physical world. This view has been defended by Frank Jackson.

- Non-reductive physicalism is the view that mental properties form a separate ontological class to physical properties: mental states (such as qualia) are not reducible to physical states. The ontological stance towards qualia in the case of non-reductive physicalism does not imply that qualia are causally inert; this is what distinguishes it from epiphenomenalism.

- Panpsychism is the view that all matter has a mental aspect, or, alternatively, all objects have a unified center of experience or point of view. Superficially, it seems to be a form of property dualism, since it regards everything as having both mental and physical properties. However, some panpsychists say that mechanical behaviour is derived from the primitive mentality of atoms and molecules—as are sophisticated mentality and organic behaviour, the difference being attributed to the presence or absence of complex structure in a compound object. So long as the reduction of non-mental properties to mental ones is in place, panpsychism is not a (strong) form of property dualism; otherwise it is.

Dual aspect theory

Dual aspect theory or dual-aspect monism is the view that the mental and the physical are two aspects of, or perspectives on, the same substance. (Thus it is a mixed position, which is monistic in some respects). In modern philosophical writings, the theory's relationship to neutral monism has become somewhat ill-defined, but one proffered distinction says that whereas neutral monism allows the context of a given group of neutral elements and the relationships into which they enter to determine whether the group can be thought of as mental, physical, both, or neither, dual-aspect theory suggests that the mental and the physical are manifestations (or aspects) of some underlying substance, entity or process that is itself neither mental nor physical as normally understood. Various formulations of dual-aspect monism also require the mental and the physical to be complementary, mutually irreducible and perhaps inseparable (though distinct).

Experiential dualism

This is a philosophy of mind that regards the degrees of freedom between mental and physical well-being as not synonymous thus implying an experiential dualism between body and mind. An example of these disparate degrees of freedom is given by Allan Wallace who notes that it is "experientially apparent that one may be physically uncomfortable—for instance, while engaging in a strenuous physical workout—while mentally cheerful; conversely, one may be mentally distraught while experiencing physical comfort". Experiential dualism notes that our subjective experience of merely seeing something in the physical world seems qualitatively different than mental processes like grief that comes from losing a loved one. This philosophy is a proponent of causal dualism, which is defined as the dual ability for mental states and physical states to affect one another. Mental states can cause changes in physical states and vice versa.

However, unlike cartesian dualism or some other systems, experiential dualism does not posit two fundamental substances in reality: mind and matter. Rather, experiential dualism is to be understood as a conceptual framework that gives credence to the qualitative difference between the experience of mental and physical states. Experiential dualism is accepted as the conceptual framework of Madhyamaka Buddhism.

Madhayamaka Buddhism goes further, finding fault with the monist view of physicalist philosophies of mind as well in that these generally posit matter and energy as the fundamental substance of reality. Nonetheless, this does not imply that the cartesian dualist view is correct, rather Madhyamaka regards as error any affirming view of a fundamental substance to reality.

In denying the independent self-existence of all the phenomena that make up the world of our experience, the Madhyamaka view departs from both the substance dualism of Descartes and the substance monism—namely, physicalism—that is characteristic of modern science. The physicalism propounded by many contemporary scientists seems to assert that the real world is composed of physical things-in-themselves, while all mental phenomena are regarded as mere appearances, devoid of any reality in and of themselves. Much is made of this difference between appearances and reality.

Indeed, physicalism, or the idea that matter is the only fundamental substance of reality, is explicitly rejected by Buddhism.

In the Madhyamaka view, mental events are no more or less real than physical events. In terms of our common-sense experience, differences of kind do exist between physical and mental phenomena. While the former commonly have mass, location, velocity, shape, size, and numerous other physical attributes, these are not generally characteristic of mental phenomena. For example, we do not commonly conceive of the feeling of affection for another person as having mass or location. These physical attributes are no more appropriate to other mental events such as sadness, a recalled image from one's childhood, the visual perception of a rose, or consciousness of any sort. Mental phenomena are, therefore, not regarded as being physical, for the simple reason that they lack many of the attributes that are uniquely characteristic of physical phenomena. Thus, Buddhism has never adopted the physicalist principle that regards only physical things as real.

Monist solutions to the mind–body problem

In contrast to dualism, monism does not accept any fundamental divisions. The fundamentally disparate nature of reality has been central to forms of eastern philosophies for over two millennia. In Indian and Chinese philosophy, monism is integral to how experience is understood. Today, the most common forms of monism in Western philosophy are physicalist. Physicalistic monism asserts that the only existing substance is physical, in some sense of that term to be clarified by our best science. However, a variety of formulations (see below) are possible. Another form of monism, idealism, states that the only existing substance is mental. Although pure idealism, such as that of George Berkeley, is uncommon in contemporary Western philosophy, a more sophisticated variant called panpsychism, according to which mental experience and properties may be at the foundation of physical experience and properties, has been espoused by some philosophers such as Alfred North Whitehead and David Ray Griffin.

Phenomenalism is the theory that representations (or sense data) of external objects are all that exist. Such a view was briefly adopted by Bertrand Russell and many of the logical positivists during the early 20th century. A third possibility is to accept the existence of a basic substance that is neither physical nor mental. The mental and physical would then both be properties of this neutral substance. Such a position was adopted by Baruch Spinoza and was popularized by Ernst Mach in the 19th century. This neutral monism, as it is called, resembles property dualism.

Physicalistic monisms

Behaviorism

Behaviorism dominated philosophy of mind for much of the 20th century, especially the first half. In psychology, behaviorism developed as a reaction to the inadequacies of introspectionism. Introspective reports on one's own interior mental life are not subject to careful examination for accuracy and cannot be used to form predictive generalizations. Without generalizability and the possibility of third-person examination, the behaviorists argued, psychology cannot be scientific. The way out, therefore, was to eliminate the idea of an interior mental life (and hence an ontologically independent mind) altogether and focus instead on the description of observable behavior.

Parallel to these developments in psychology, a philosophical behaviorism (sometimes called logical behaviorism) was developed. This is characterized by a strong verificationism, which generally considers unverifiable statements about interior mental life pointless. For the behaviorist, mental states are not interior states on which one can make introspective reports. They are just descriptions of behavior or dispositions to behave in certain ways, made by third parties to explain and predict another's behavior.

Philosophical behaviorism has fallen out of favor since the latter half of the 20th century, coinciding with the rise of cognitivism.

Identity theory

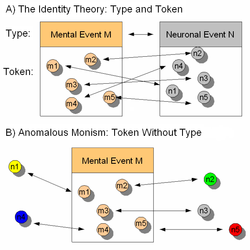

Type physicalism (or type-identity theory) was developed by John Smart and Ullin Place as a direct reaction to the failure of behaviorism. These philosophers reasoned that, if mental states are something material, but not behavioral, then mental states are probably identical to internal states of the brain. In very simplified terms: a mental state M is nothing other than brain state B. The mental state "desire for a cup of coffee" would thus be nothing more than the "firing of certain neurons in certain brain regions".

On the other hand, even granted the above, it does not follow that identity theories of all types must be abandoned. According to token identity theories, the fact that a certain brain state is connected with only one mental state of a person does not have to mean that there is an absolute correlation between types of mental state and types of brain state. The type–token distinction can be illustrated by a simple example: the word "green" contains four types of letters (g, r, e, n) with two tokens (occurrences) of the letter e along with one each of the others. The idea of token identity is that only particular occurrences of mental events are identical with particular occurrences or tokenings of physical events. Anomalous monism (see below) and most other non-reductive physicalisms are token-identity theories. Despite these problems, there is a renewed interest in the type identity theory today, primarily due to the influence of Jaegwon Kim.

Functionalism

Functionalism was formulated by Hilary Putnam and Jerry Fodor as a reaction to the inadequacies of the identity theory. Putnam and Fodor saw mental states in terms of an empirical computational theory of the mind. At about the same time or slightly after, D.M. Armstrong and David Kellogg Lewis formulated a version of functionalism that analyzed the mental concepts of folk psychology in terms of functional roles. Finally, Wittgenstein's idea of meaning as use led to a version of functionalism as a theory of meaning, further developed by Wilfrid Sellars and Gilbert Harman. Another one, psychofunctionalism, is an approach adopted by the naturalistic philosophy of mind associated with Jerry Fodor and Zenon Pylyshyn.

Mental states are characterized by their causal relations with other mental states and with sensory inputs and behavioral outputs. Functionalism abstracts away from the details of the physical implementation of a mental state by characterizing it in terms of non-mental functional properties. For example, a kidney is characterized scientifically by its functional role in filtering blood and maintaining certain chemical balances.

Non-reductive physicalism

Non-reductionist philosophers hold firmly to two essential convictions with regard to mind–body relations: 1) Physicalism is true and mental states must be physical states, but 2) All reductionist proposals are unsatisfactory: mental states cannot be reduced to behavior, brain states or functional states. Hence, the question arises whether there can still be a non-reductive physicalism. Donald Davidson's anomalous monism is an attempt to formulate such a physicalism. He "thinks that when one runs across what are traditionally seen as absurdities of Reason, such as akrasia or self-deception, the personal psychology framework is not to be given up in favor of the subpersonal one, but rather must be enlarged or extended so that the rationality set out by the principle of charity can be found elsewhere."

Davidson uses the thesis of supervenience: mental states supervene on physical states, but are not reducible to them. "Supervenience" therefore describes a functional dependence: there can be no change in the mental without some change in the physical–causal reducibility between the mental and physical without ontological reducibility.

Non-reductive physicalism, however, is irreconcilable with self-identity over time. The brain goes on from one moment of time to another; the brain thus has identity through time. But its states of awareness do not go on from one moment to the next. There is no enduring self – no “I” (capital-I) that goes on from one moment to the next. An analogy of the self or the “I” would be the flame of a candle. The candle and the wick go on from one moment to the next, but the flame does not go on. There is a different flame at each moment of the candle’s burning. The flame displays a type of continuity in that the candle does not go out while it is burning, but there is not really any identity of the flame from one moment to another over time. The scenario is similar on non-reductive physicalism with states of awareness. Every state of the brain at different times has a different state of awareness related to it, but there is no enduring self or “I” from one moment to the next. Similarly, it is an illusion that one is the same individual who walked into class this morning. In fact, one is not the same individual because there is no personal identity over time. If one does exist and one is the same individual who entered into class this morning, then a non-reductive physicalist view of the self should be dismissed.

Because non-reductive physicalist theories attempt to both retain the ontological distinction between mind and body and try to solve the "surfeit of explanations puzzle" in some way; critics often see this as a paradox and point out the similarities to epiphenomenalism, in that it is the brain that is seen as the root "cause" not the mind, and the mind seems to be rendered inert.

Epiphenomenalism regards one or more mental states as the byproduct of physical brain states, having no influence on physical states. The interaction is one-way (solving the "surfeit of explanations puzzle") but leaving us with non-reducible mental states (as a byproduct of brain states) – causally reducible, but ontologically irreducible to physical states. Pain would be seen by epiphenomenalists as being caused by the brain state but as not having effects on other brain states, though it might have effects on other mental states (i.e. cause distress).

Weak emergentism

Weak emergentism is a form of "non-reductive physicalism" that involves a layered view of nature, with the layers arranged in terms of increasing complexity and each corresponding to its own special science. Some philosophers hold that emergent properties causally interact with more fundamental levels, while others maintain that higher-order properties simply supervene over lower levels without direct causal interaction. The latter group therefore holds a less strict, or "weaker", definition of emergentism, which can be rigorously stated as follows: a property P of composite object O is emergent if it is metaphysically impossible for another object to lack property P if that object is composed of parts with intrinsic properties identical to those in O and has those parts in an identical configuration.

Sometimes emergentists use the example of water having a new property when Hydrogen H and Oxygen O combine to form H2O (water). In this example there "emerges" a new property of a transparent liquid that would not have been predicted by understanding hydrogen and oxygen as gases. This is analogous to physical properties of the brain giving rise to a mental state. Emergentists try to solve the notorious mind–body gap this way. One problem for emergentism is the idea of "causal closure" in the world that does not allow for a mind-to-body causation.

Eliminative materialism

If one is a materialist and believes that all aspects of our common-sense psychology will find reduction to a mature cognitive neuroscience, and that non-reductive materialism is mistaken, then one can adopt a final, more radical position: eliminative materialism.

There are several varieties of eliminative materialism, but all maintain that our common-sense "folk psychology" badly misrepresents the nature of some aspect of cognition. Eliminativists such as Patricia and Paul Churchland argue that while folk psychology treats cognition as fundamentally sentence-like, the non-linguistic vector/matrix model of neural network theory or connectionism will prove to be a much more accurate account of how the brain works.

The Churchlands often invoke the fate of other, erroneous popular theories and ontologies that have arisen in the course of history. For example, Ptolemaic astronomy served to explain and roughly predict the motions of the planets for centuries, but eventually this model of the solar system was eliminated in favor of the Copernican model. The Churchlands believe the same eliminative fate awaits the "sentence-cruncher" model of the mind in which thought and behavior are the result of manipulating sentence-like states called "propositional attitudes".

Mysterianism

Some philosophers take an epistemic approach and argue that the mind–body problem is currently unsolvable, and perhaps will always remain unsolvable to human beings. This is usually termed New mysterianism. Colin McGinn holds that human beings are cognitively closed in regards to their own minds. According to McGinn human minds lack the concept-forming procedures to fully grasp how mental properties such as consciousness arise from their causal basis. An example would be how an elephant is cognitively closed in regards to particle physics.

A more moderate conception has been expounded by Thomas Nagel, which holds that the mind–body problem is currently unsolvable at the present stage of scientific development and that it might take a future scientific paradigm shift or revolution to bridge the explanatory gap. Nagel posits that in the future a sort of "objective phenomenology" might be able to bridge the gap between subjective conscious experience and its physical basis.

Linguistic criticism of the mind–body problem

Each attempt to answer the mind–body problem encounters substantial problems. Some philosophers argue that this is because there is an underlying conceptual confusion. These philosophers, such as Ludwig Wittgenstein and his followers in the tradition of linguistic criticism, therefore reject the problem as illusory. They argue that it is an error to ask how mental and biological states fit together. Rather it should simply be accepted that human experience can be described in different ways—for instance, in a mental and in a biological vocabulary. Illusory problems arise if one tries to describe the one in terms of the other's vocabulary or if the mental vocabulary is used in the wrong contexts. This is the case, for instance, if one searches for mental states of the brain. The brain is simply the wrong context for the use of mental vocabulary—the search for mental states of the brain is therefore a category error or a sort of fallacy of reasoning.

Today, such a position is often adopted by interpreters of Wittgenstein such as Peter Hacker. However, Hilary Putnam, the originator of functionalism, has also adopted the position that the mind–body problem is an illusory problem which should be dissolved according to the manner of Wittgenstein.

Naturalism and its problems

The thesis of physicalism is that the mind is part of the material (or physical) world. Such a position faces the problem that the mind has certain properties that no other material thing seems to possess. Physicalism must therefore explain how it is possible that these properties can nonetheless emerge from a material thing. The project of providing such an explanation is often referred to as the "naturalization of the mental". Some of the crucial problems that this project attempts to resolve include the existence of qualia and the nature of intentionality.

Qualia

Many mental states seem to be experienced subjectively in different ways by different individuals. And it is characteristic of a mental state that it has some experiential quality, e.g. of pain, that it hurts. However, the sensation of pain between two individuals may not be identical, since no one has a perfect way to measure how much something hurts or of describing exactly how it feels to hurt. Philosophers and scientists therefore ask where these experiences come from. The existence of cerebral events, in and of themselves, cannot explain why they are accompanied by these corresponding qualitative experiences. The puzzle of why many cerebral processes occur with an accompanying experiential aspect in consciousness seems impossible to explain.

Yet it also seems to many that science will eventually have to explain such experiences. This follows from an assumption about the possibility of reductive explanations. According to this view, if an attempt can be successfully made to explain a phenomenon reductively (e.g., water), then it can be explained why the phenomenon has all of its properties (e.g., fluidity, transparency). In the case of mental states, this means that there needs to be an explanation of why they have the property of being experienced in a certain way.

The 20th-century German philosopher Martin Heidegger criticized the ontological assumptions underpinning such a reductive model, and claimed that it was impossible to make sense of experience in these terms. This is because, according to Heidegger, the nature of our subjective experience and its qualities is impossible to understand in terms of Cartesian "substances" that bear "properties". Another way to put this is that the very concept of qualitative experience is incoherent in terms of—or is semantically incommensurable with the concept of—substances that bear properties.

This problem of explaining introspective first-person aspects of mental states and consciousness in general in terms of third-person quantitative neuroscience is called the explanatory gap. There are several different views of the nature of this gap among contemporary philosophers of mind. David Chalmers and the early Frank Jackson interpret the gap as ontological in nature; that is, they maintain that qualia can never be explained by science because physicalism is false. There are two separate categories involved and one cannot be reduced to the other. An alternative view is taken by philosophers such as Thomas Nagel and Colin McGinn. According to them, the gap is epistemological in nature. For Nagel, science is not yet able to explain subjective experience because it has not yet arrived at the level or kind of knowledge that is required. We are not even able to formulate the problem coherently. For McGinn, on other hand, the problem is one of permanent and inherent biological limitations. We are not able to resolve the explanatory gap because the realm of subjective experiences is cognitively closed to us in the same manner that quantum physics is cognitively closed to elephants. Other philosophers liquidate the gap as purely a semantic problem. This semantic problem, of course, led to the famous "Qualia Question", which is: Does Red cause Redness?

Intentionality

Intentionality is the capacity of mental states to be directed towards (about) or be in relation with something in the external world. This property of mental states entails that they have contents and semantic referents and can therefore be assigned truth values. When one tries to reduce these states to natural processes there arises a problem: natural processes are not true or false, they simply happen. It would not make any sense to say that a natural process is true or false. But mental ideas or judgments are true or false, so how then can mental states (ideas or judgments) be natural processes? The possibility of assigning semantic value to ideas must mean that such ideas are about facts. Thus, for example, the idea that Herodotus was a historian refers to Herodotus and to the fact that he was a historian. If the fact is true, then the idea is true; otherwise, it is false. But where does this relation come from? In the brain, there are only electrochemical processes and these seem not to have anything to do with Herodotus.

Philosophy of perception

Philosophy of perception is concerned with the nature of perceptual experience and the status of perceptual objects, in particular how perceptual experience relates to appearances and beliefs about the world. The main contemporary views within philosophy of perception include naive realism, enactivism and representational views.

Philosophy of mind and science

Humans are corporeal beings and, as such, they are subject to examination and description by the natural sciences. Since mental processes are intimately related to bodily processes, the descriptions that the natural sciences furnish of human beings play an important role in the philosophy of mind. There are many scientific disciplines that study processes related to the mental. The list of such sciences includes: biology, computer science, cognitive science, cybernetics, linguistics, medicine, pharmacology, and psychology.

Neurobiology

The theoretical background of biology, as is the case with modern natural sciences in general, is fundamentally materialistic. The objects of study are, in the first place, physical processes, which are considered to be the foundations of mental activity and behavior. The increasing success of biology in the explanation of mental phenomena can be seen by the absence of any empirical refutation of its fundamental presupposition: "there can be no change in the mental states of a person without a change in brain states."

Within the field of neurobiology, there are many subdisciplines that are concerned with the relations between mental and physical states and processes: Sensory neurophysiology investigates the relation between the processes of perception and stimulation. Cognitive neuroscience studies the correlations between mental processes and neural processes. Neuropsychology describes the dependence of mental faculties on specific anatomical regions of the brain. Lastly, evolutionary biology studies the origins and development of the human nervous system and, in as much as this is the basis of the mind, also describes the ontogenetic and phylogenetic development of mental phenomena beginning from their most primitive stages. Evolutionary biology furthermore places tight constraints on any philosophical theory of the mind, as the gene-based mechanism of natural selection does not allow any giant leaps in the development of neural complexity or neural software but only incremental steps over long time periods.

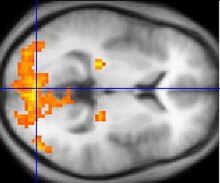

The methodological breakthroughs of the neurosciences, in particular the introduction of high-tech neuroimaging procedures, has propelled scientists toward the elaboration of increasingly ambitious research programs: one of the main goals is to describe and comprehend the neural processes which correspond to mental functions (see: neural correlate). Several groups are inspired by these advances.

Computer science

Computer science concerns itself with the automatic processing of information (or at least with physical systems of symbols to which information is assigned) by means of such things as computers. From the beginning, computer programmers have been able to develop programs that permit computers to carry out tasks for which organic beings need a mind. A simple example is multiplication. It is not clear whether computers could be said to have a mind. Could they, someday, come to have what we call a mind? This question has been propelled into the forefront of much philosophical debate because of investigations in the field of artificial intelligence (AI).

Within AI, it is common to distinguish between a modest research program and a more ambitious one: this distinction was coined by John Searle in terms of a weak AI and strong AI. The exclusive objective of "weak AI", according to Searle, is the successful simulation of mental states, with no attempt to make computers become conscious or aware, etc. The objective of strong AI, on the contrary, is a computer with consciousness similar to that of human beings. The program of strong AI goes back to one of the pioneers of computation Alan Turing. As an answer to the question "Can computers think?", he formulated the famous Turing test. Turing believed that a computer could be said to "think" when, if placed in a room by itself next to another room that contained a human being and with the same questions being asked of both the computer and the human being by a third party human being, the computer's responses turned out to be indistinguishable from those of the human. Essentially, Turing's view of machine intelligence followed the behaviourist model of the mind—intelligence is as intelligence does. The Turing test has received many criticisms, among which the most famous is probably the Chinese room thought experiment formulated by Searle.

The question about the possible sensitivity (qualia) of computers or robots still remains open. Some computer scientists believe that the specialty of AI can still make new contributions to the resolution of the "mind–body problem". They suggest that based on the reciprocal influences between software and hardware that takes place in all computers, it is possible that someday theories can be discovered that help us to understand the reciprocal influences between the human mind and the brain (wetware).

Psychology

Psychology is the science that investigates mental states directly. It uses generally empirical methods to investigate concrete mental states like joy, fear or obsessions. Psychology investigates the laws that bind these mental states to each other or with inputs and outputs to the human organism.

An example of this is the psychology of perception. Scientists working in this field have discovered general principles of the perception of forms. A law of the psychology of forms says that objects that move in the same direction are perceived as related to each other. This law describes a relation between visual input and mental perceptual states. However, it does not suggest anything about the nature of perceptual states. The laws discovered by psychology are compatible with all the answers to the mind–body problem already described.

Cognitive science

Cognitive science is the interdisciplinary scientific study of the mind and its processes. It examines what cognition is, what it does, and how it works. It includes research on intelligence and behavior, especially focusing on how information is represented, processed, and transformed (in faculties such as perception, language, memory, reasoning, and emotion) within nervous systems (human or other animal) and machines (e.g. computers). Cognitive science consists of multiple research disciplines, including psychology, artificial intelligence, philosophy, neuroscience, linguistics, anthropology, sociology, and education. It spans many levels of analysis, from low-level learning and decision mechanisms to high-level logic and planning; from neural circuitry to modular brain organisation. Rowlands argues that cognition is enactive, embodied, embedded, affective and (potentially) extended. The position is taken that the "classical sandwich" of cognition sandwiched between perception and action is artificial; cognition has to be seen as a product of a strongly coupled interaction that cannot be divided this way.

Near-death research

In the field of near-death research, the following phenomenon, among others, occurs: For example, during some brain operations the brain is artificially and measurably deactivated. Nevertheless, some patients report during this phase that they have perceived what is happening in their surroundings, i.e. that they have had consciousness. Patients also report experiences during a cardiac arrest. There is the following problem: As soon as the brain is no longer supplied with blood and thus with oxygen after a cardiac arrest, the brain ceases its normal operation after about 15 seconds, i.e. the brain falls into a state of unconsciousness.

Philosophy of mind in the continental tradition

Most of the discussion in this article has focused on one style or tradition of philosophy in modern Western culture, usually called analytic philosophy (sometimes described as Anglo-American philosophy). Many other schools of thought exist, however, which are sometimes subsumed under the broad (and vague) label of continental philosophy. In any case, though topics and methods here are numerous, in relation to the philosophy of mind the various schools that fall under this label (phenomenology, existentialism, etc.) can globally be seen to differ from the analytic school in that they focus less on language and logical analysis alone but also take in other forms of understanding human existence and experience. With reference specifically to the discussion of the mind, this tends to translate into attempts to grasp the concepts of thought and perceptual experience in some sense that does not merely involve the analysis of linguistic forms.

Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, first published in 1781 and presented again with major revisions in 1787, represents a significant intervention into what will later become known as the philosophy of mind. Kant's first critique is generally recognized as among the most significant works of modern philosophy in the West. Kant is a figure whose influence is marked in both continental and analytic/Anglo-American philosophy. Kant's work develops an in-depth study of transcendental consciousness, or the life of the mind as conceived through the universal categories of understanding.

In Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's Philosophy of Mind (frequently translated as Philosophy of Spirit or Geist), the third part of his Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences, Hegel discusses three distinct types of mind: the "subjective mind/spirit", the mind of an individual; the "objective mind/spirit", the mind of society and of the State; and the "Absolute mind/spirit", the position of religion, art, and philosophy. See also Hegel's The Phenomenology of Spirit. Nonetheless, Hegel's work differs radically from the style of Anglo-American philosophy of mind.

In 1896, Henri Bergson made in Matter and Memory "Essay on the relation of body and spirit" a forceful case for the ontological difference of body and mind by reducing the problem to the more definite one of memory, thus allowing for a solution built on the empirical test case of aphasia.

In modern times, the two main schools that have developed in response or opposition to this Hegelian tradition are phenomenology and existentialism. Phenomenology, founded by Edmund Husserl, focuses on the contents of the human mind (see noema) and how processes shape our experiences.

Existentialism, a school of thought founded upon the work of Søren Kierkegaard, focuses on Human predicament and how people deal with the situation of being alive. Existential-phenomenology represents a major branch of continental philosophy (they are not contradictory), rooted in the work of Husserl but expressed in its fullest forms in the work of Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. See Heidegger's Being and Time, Merleau-Ponty's Phenomenology of Perception, Sartre's Being and Nothingness, and Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex.

There are countless subjects that are affected by the ideas developed in the philosophy of mind. Clear examples of this are the nature of death and its definitive character, the nature of emotion, of perception and of memory. Questions about what a person is and what his or her identity have to do with the philosophy of mind. There are two subjects that, in connection with the philosophy of the mind, have aroused special attention: free will and the self.

Free will

In the context of philosophy of mind, the problem of free will takes on renewed intensity. This is the case for materialistic determinists. According to this position, natural laws completely determine the course of the material world. Mental states, and therefore the will as well, would be material states, which means human behavior and decisions would be completely determined by natural laws. Some take this reasoning a step further: people cannot determine by themselves what they want and what they do. Consequently, they are not free.

This argumentation is rejected, on the one hand, by the compatibilists. Those who adopt this position suggest that the question "Are we free?" can only be answered once we have determined what the term "free" means. The opposite of "free" is not "caused" but "compelled" or "coerced". It is not appropriate to identify freedom with indetermination. A free act is one where the agent could have done otherwise if it had chosen otherwise. In this sense a person can be free even though determinism is true. The most important compatibilist in the history of the philosophy was David Hume. More recently, this position is defended, for example, by Daniel Dennett.

On the other hand, there are also many incompatibilists who reject the argument because they believe that the will is free in a stronger sense called libertarianism. These philosophers affirm the course of the world is either a) not completely determined by natural law where natural law is intercepted by physically independent agency, b) determined by indeterministic natural law only, or c) determined by indeterministic natural law in line with the subjective effort of physically non-reducible agency. Under Libertarianism, the will does not have to be deterministic and, therefore, it is potentially free. Critics of the second proposition (b) accuse the incompatibilists of using an incoherent concept of freedom. They argue as follows: if our will is not determined by anything, then we desire what we desire by pure chance. And if what we desire is purely accidental, we are not free. So if our will is not determined by anything, we are not free.

Self

The philosophy of mind also has important consequences for the concept of "self". If by "self" or "I" one refers to an essential, immutable nucleus of the person, some modern philosophers of mind, such as Daniel Dennett believe that no such thing exists. According to Dennett and other contemporaries, the self is considered an illusion. The idea of a self as an immutable essential nucleus derives from the idea of an immaterial soul. Such an idea is unacceptable to modern philosophers with physicalist orientations and their general skepticism of the concept of "self" as postulated by David Hume, who could never catch himself not doing, thinking or feeling anything. However, in the light of empirical results from developmental psychology, developmental biology and neuroscience, the idea of an essential inconstant, material nucleus—an integrated representational system distributed over changing patterns of synaptic connections—seems reasonable.