An Earthship is a type of passive solar earth shelter that is made of both natural and upcycled materials such as earth-packed tires, pioneered by architect Michael Reynolds.

Earthships are predicated upon the idea that there are six human needs which can be addressed through environmentally sustainable building design:

- Energy: Thermal and/or solar heating and cooling, solar and wind electricity

- Garbage management: Reuse and recycling built into construction and daily living

- Sewage treatment: Self-contained sewage treatment and water recycling

- Shelter: Building with natural and recycled materials

- Clean Water: Water harvesting and long term storage

- Food: In-home organic food production capability

Earthship structures are intended to be "off-the-grid-ready" homes, with minimal reliance on public utilities and fossil fuels. They are constructed to use available natural resources, especially energy from the sun and rain water. They are designed with thermal mass construction and natural cross-ventilation to regulate indoor temperature, and the designs are intentionally uncomplicated and mainly single-story, so that people with little building knowledge can construct them.

History

The Earthship architecture concept began to take shape in the 1970s.

The architect Michael Reynolds wanted to create a home that would do three things. First, it would utilize sustainable architecture, and material indigenous to the local area or recycled materials wherever possible. Second, it would rely on natural energy sources and be independent from the "grid". Third, it would be feasible for a person with no specialized construction skills to build. Eventually, Reynolds's vision was transformed into the common U-shaped earth-filled tire homes seen today.

The name is based on the idea of a ship or a space ship. Both of those structures need to provide everything for their inhabitants to survive: shelter, power, waste management, water, and food. The same idea is used for an Earthship: to be a sustainable structure to fulfill our needs.

Construction and design

The buildings are often horseshoe-shaped due to the difficulty of creating sharp 90 degree angles with rammed tires. In Reynolds's prototype at Taos, the opening of the horseshoe faces 10–15 degrees east of south to maximize natural light and solar-gain during the winter months, with windows on sun-facing walls admitting light and heat.

The book, Earthship I, describes how to find the best angle depending on the building's geographic location. The thick and dense walls provide thermal mass that naturally regulates the interior temperature during both cold and hot outside temperatures. The outer walls in the majority of Earthships are made of earth-rammed tires, but any dense material with a potential to store heat, such as concrete, adobe, earth bags, or stone, could in principle be used to create a building similar to an Earthship. The tire walls are staggered like traditional brick work, and often have "concrete half blocks" every other course, to equal the length of the staggered tire below. In an effort to cut down the use of concrete even further, they also use "squishies" - tires rammed in between a tight space to even out the course or to compensate for varying tire size.

The rammed earth tires of an Earthship are assembled by teams of two people. One person shovels dirt and places it into the tire one scoop at a time. The other person, who stands on the tire, uses a sledgehammer to pack the dirt in while moving in a circle around the tire to keep the dirt even and to avoid warping the tire. Rammed earth tires can weigh up to 300 pounds, so they are typically filled in place. Because the tire is full of soil, it does not burn when exposed to fire. In colder climates, extra insulation is added on the outside of the tire walls. It uses modern technologies such as solar cells, solar collectors and water filtering systems.

On top of the tire walls are either "can and concrete bond beams" made of recycled cans joined by concrete, or wooden bond beams with wooden shoes. These are attached to the tire walls using concrete anchors, poured blocks of concrete inside the top tires. Wooden shimming blocks placed on top of the wooden bond beam make up the wooden shoes. The wooden bond beam consists of two layers of lumber bolted on to the concrete anchors. Re-bar is used to "nail" the wooden shoes to the wooden bond beam.

Internal, non-load-bearing walls are often made of a honeycomb of recycled cans joined by concrete; these are nicknamed tin can walls. These walls are usually thickly plastered with adobe, and resemble traditional adobe walls when finished.

The roof is made using trusses, or wooden support beams called vigas, that rest on the wooden shoes or the tin can walls placed on the bond beams. The roof as well as the north, east and west facing walls are heavily insulated to reduce heat loss.

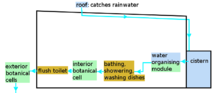

Water

Earthships are designed to catch all the water they need from the local environment. Water used in an Earthship is harvested from rain, snow, and condensation. As water collects on the roof, it is channeled through a silt-catching device and into a cistern. The cisterns are positioned to gravity-feed a water organization module (WOM) that filters out bacteria and contaminants, making it suitable for drinking. The WOM consists of filters and a DC-pump. Water is then pushed into a conventional pressure tank to create common household water pressure.

Water collected in this fashion is used for every household activity except flushing toilets. The toilets are flushed with greywater which has been used at least once already. Typically it is filtered waste-water from sinks and showers.

Greywater, recycled water unsuitable for drinking, is used within the Earthship primarily for flushing toilets. Before the greywater can be reused, it is channeled through a grease and particle filter/digester and into a 30–60" deep rubber-lined botanical cell, a miniature living machine, within the Earthship. Here the water is oxygenated and filtered using bacteria and plants to reduce the nutrient load. Water from the low end of the botanical cell is directed through a peat moss filter and collected in a reservoir or well. The reclaimed water is passed once more through a greywater board and used to flush conventional toilets.

Black water is water that has been used in a toilet. Earthships utilize anaerobic digestion in their septic tanks, which naturally separate solid waste. The black water is used in concrete cells containing plants, separate from the grey water plants in the greenhouse; it may also be used in exterior planters. Studies on the safety of growing food plants in a black water system show low levels of E. coli bacteria. It is not recommended to plant edibles in black water; building permits may be refused for plans indicating such usage of black water.

Where it is not possible to use flush-toilets operating on water, dry solar toilets are recommended.

Power

Earthships are designed to collect and store their own energy. The majority of electrical energy is harvested from the sun and wind. Photovoltaic panels and wind turbines on or near the Earthship generate DC electricity that is stored in deep-cycle batteries. The batteries are housed in a purpose-built room on the roof. Additional energy can be obtained from gasoline-powered generators or by integrating with the city grid. For Canadian winters the solar cell exposed surface areas needs to be increased by over three times.

In an Earthship, a Power Organizing Module (POM) takes a proportion of stored energy from batteries and invert it for AC use. The Power Organizing Module is a prefabricated system provided by Earthship Biotecture that is simply attached to a wall on the interior of the Earthship and wired in a conventional manner. It includes the necessary equipment such as circuit breakers and converters. The energy run through the Power Organizing Module can be used to run any household appliance including washing machines, computers, kitchen appliances, print machines, and vacuums. Ideally, none of the electrical energy in an Earthship is used for heating or cooling.

Thermal performance

Earthships rely on a balance between the solar heat gain and the ability of the tire walls and subsoil to transport and store heat. They are designed to use the properties of thermal mass and with the intent that the exterior earth-rammed tire walls provide thermal mass that will soak up heat during the day and radiate heat during the night, keeping the interior climate relatively comfortable all day. In addition to the exterior tire walls, some Earthships are sunk into the earth to take advantage of earth-sheltering to reduce temperature fluctuations.

Some earthship structures have suffered from heat loss into the ground during the heating season. This may be due to climatic differences between New Mexico where earthships were first built and cloudier, cooler, and wetter climates. Thermal performance problems may also have occurred due to thermal mass being erroneously equated to R-value. The imperial R-value of soil is about 1 per foot. Malcolm Wells, an architect and authority on earth-sheltered design, recommends an imperial R-value 10 insulation between deep soils and heated spaces. Wells's insulation recommendations increase as the depth of the soil decreases (a negative correlation).

In addition to thermal mass, Earthships use passive solar heating and cooling. Large front windows with integrated shades, trombe walls and other technologies such as skylights or Steve Baer's "Track Rack" solar trackers are used for heat regulation. Earthships are positioned so that its principal wall, which is nonstructural and made mostly of glass sheets, faces directly towards the equator. This positioning allows for optimum solar exposure. To allow the sun to heat the mass of the Earthship, the solar-oriented wall is angled so that it is perpendicular to light from the winter sun. This allows for maximum exposure in the winter, when heat is wanted, and lesser exposure in the summer, when heat is to be avoided. Some Earthships, especially those built in colder climates, use insulated shading on the solar-orientated wall to reduce heat loss during the night.

Current Earthship designs like the global module have a "double greenhouse" where the outside glass is angled towards the equator, and an internal glass wall forms a walk way or hallway as you step into the Earthship. This greenhouse is primarily used to grow food; it also creates a barrier for the 'comfort zone' inside the house.

Ventilation

Earthships structures have a natural ventilation system based on convection. A 30 ft pipe extends from the interior of the house under the berm, cooling the air by the time it gets to the comfort zone. As the hot air rises, the system creates a steady airflow - of cooler air coming in, and warmer air blowing out though a smaller vented window in the greenhouse.

Around the world

Africa

The first earthship in South Africa was built by Angel and Yvonne Kamp between 1996 and 1998. They rammed a total of 1,500 tires for the walls. The Earthship, near Hermanus, is located in a 60 hectare private nature reserve which is part of a 500 hectare area enclosed in a game fence and borders the Walker Bay Nature Reserve.

The second earthship in South Africa is a recycling centre in Khayelitsha run as a swop shop concept. The centre was finished in December 2010. Another low cost house built with tires is in development in Bloemfontein.

A project nearing completion in South Africa is a combined living quarters and the Sonskip / Aardskip open air museum in Orania. This earthship is based on the global earthship model and is built with a foundation of tires, has roof bearing walls built with earthbags, and interior walls built with cob, cans and plastic bottles. This earthship adheres to all six principles of an earthship. This is the largest earthbag earthship in the world.

A residential house was in the planning phase for Swaziland in 2013.

In 2011, construction began on the Goderich Waldorf School of Sierra Leone. The school was the first educational institution to use earthship architecture. Although Mike Reynolds and a team of interns helped complete the first two classrooms, the majority of the building was built by community members who had been trained in Reynolds' building techniques.

A new project was scheduled to commence in Malawi in October 2013.

Australia

Earthship Ironbank was built by Martin and Zoe Freney south-east of Adelaide in South Australia and is the first earthship constructed with council permission in Australia.

Europe

In 2000, Michael Reynolds and his team came to build the first residential earthship in Boingt (Belgium). While water, power module, solar panels and the team were on their way to Europe, the mayor of Boingt put his veto on the building permit. Josephine Overeem, the woman who wanted to build the earthship, and Michael Reynolds decided to do a demonstration model in her back yard at her residence in Strombeek (Belgium). CLEVEL invited Reynolds from Belgium to Brighton in the UK, and orchestrated plans for the earthship in Brighton, started in 2003. This was the beginning of a series of trips made by Reynolds and the construction of earthships in the UK, France and the Netherlands.

In 2004, the very first Earthship in the UK was opened at Kinghorn Loch in Fife, Scotland. It was built by volunteers of the SCI charity. In 2005, the first earthship in England was established in Stanmer Park, Brighton with the Low Carbon Trust. In 2007, CLEVEL and Earthship Biotecture obtained planning permission to build on a development site overlooking the Brighton Marina in the UK. The application followed a six-month feasibility study, orchestrated by Daren Howarth, Kevan Trott and Michael Reynolds and funded by the UK Environment Agency and the Energy Savings Trust. The successful application was for sixteen one, two, and three-bedroom earthship homes on this site, expected to have a sale price of 250 - 400,000 pounds. The homes are all designed according to basic earthship principles developed in the United States and adapted to the UK. 15,000 tires will be recycled to construct these homes (the UK burns approximately 40 million tires each year). The plans include the enhancement of habitats on the site for lizards that already live there, which is the reasoning behind entitling the project "The Lizard". This would have been the first development of its kind in Europe.

The first official Earthship home in mainland Europe with official planning permission approval was built in a small French village called Ger. The home, which was owned by Kevan and Gillian Trott, was built in April 2007 by Kevan, Mike Reynolds and an Earthship Crew from Taos, it was sold to a family in 2014. The design was modified for a European climate and is seen as the first of many for the European arena. It is currently used as a holiday home for eco-tourists.

Further adaptation to the European context was undertaken by Daren Howarth and Adrianne Nortje in Brittany, France. They obtained full planning permission in 2007 and finished the Brittany Groundhouse as their own home during 2009. The build experience and learning is documented in the UK Grand Designs series and in their book.

Earthships have been built or are being built in Portugal, Spain, France, Belgium, The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Estonia and Czech Republic.

The first official earthship district (23 earthships) in Europe was developed in Olst (the Netherlands). Building started in Spring 2012 and completed in December, 2014. In Belgium, 1 earthship hybrid is also being built, intended as demonstration buildings. Since it is illegal to use tires in Belgium (for risk of leaking toxic metals like lead and zinc), the project uses earthbags instead.

The Earthships built in Europe by Michael Reynolds have to be adapted to perform as intended. Some showed problems with moisture and mould. Some research into thermal performance was done by the University of Brighton on the Brighton Earthship. The first successful construction of an Earthship in Germany (Tempelhof/Kreßberg, 2015/16) used fewer thermal bridges but increased insulation in cooperation with a Fraunhofer Institute to prevent any mould problems.

Central America

An earthship was constructed in 2015 by the Atkinson family in southern Belize. It featured on the June 2015 UK Channel 4 TV programme Escape to the Wild, season 1, episode 3.

Guatemala also hosts two earthships.

South America

The first Earthship in South America was built in January 2014 in the town of Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. Today this building functions as a visitor center and example of self-sustainable living.

In March 2016, an Earthship school was built in Jaureguiberry, Uruguay.

In popular culture

The film Garbage Warrior is about Earthships and Reynolds' struggle with obtaining permits to build out of unconventional material and off the grid. The average cost in 2019 including labour and land is about $500,000.