| Orbital human spaceflight (beyond Kármán line) | ||

| Program | Years | Flights |

|---|---|---|

| Vostok | 1961-1963 | 6 |

| Mercury | 1962-1963 | 4 |

| Voskhod | 1964-1965 | 2 |

| Gemini | 1965-1966 | 10 |

| Soyuz | 1967–present | 137 |

| Apollo | 1968-1972 | 11 |

| Skylab | 1973-1974 | 3 |

| Apollo-Soyuz | 1975 | 1 |

| Space Shuttle | 1981-2011 | 135 |

| Shenzhou | 2003–present | 6 |

| Crew Dragon | 2020 | 2 |

|

| ||

| Suborbital human spaceflight | ||

| Program | Year | Flights |

| Mercury | 1961 | 2 |

| X-15 | 1963 | 2 |

| Soyuz 18a | 1975 | 1 |

| SpaceShipOne | 2004 | 3 |

Spaceflight began in the 20th century following theoretical and practical breakthroughs by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and Robert H. Goddard. The Soviet Union took the lead in the post-war Space Race, launching the first satellite, the first man and the first woman into orbit. The United States caught up with, and then passed, their Soviet rivals during the mid-1960s, landing the first man on the Moon in 1969. In the same period, France, the United Kingdom, Japan and China were concurrently developing more limited launch capabilities.

Following the end of the Space Race, spaceflight has been characterised by greater international co-operation, cheaper access to low Earth orbit and an expansion of commercial ventures. Interplanetary probes have visited all of the planets in the Solar System, and humans have remained in orbit for long periods aboard space stations such as Mir and the ISS. Most recently, China has emerged as the third nation with the capability to launch independent crewed missions, whilst operators in the commercial sector have developed re-usable booster systems and craft launched from airborne platforms.

In 2020, SpaceX became the first commercial operator to successfully launch a crewed mission to the International Space Station with Crew Dragon Demo-2, whose name vary depending on the organization.

Background

At the beginning of the 20th century, there was a burst of scientific investigation into interplanetary travel, inspired by fiction by writers such as Jules Verne (From the Earth to the Moon, Around the Moon) and H.G. Wells (The First Men in the Moon, The War of the Worlds).

The first realistic proposal of spaceflight goes back to Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. His most famous work, "Исследование мировых пространств реактивными приборами" (Issledovanie mirovikh prostranstv reaktivnimi priborami, or The Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices), was published in 1903, but this theoretical work was not widely influential outside Russia.

Spaceflight became an engineering possibility with the work of Robert H. Goddard's publication in 1919 of his paper "A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes", where his application of the de Laval nozzle to liquid fuel rockets gave sufficient power for interplanetary travel to become possible. This paper was highly influential on Hermann Oberth and Wernher Von Braun, later key players in spaceflight.

In 1929, the Slovene officer Hermann Noordung was the first to imagine a complete space station in his book The Problem of Space Travel.

The first rocket to reach space was a German V-2 rocket, on a vertical test flight in June 1944. After the war ended, the research and development branch of the (British) Ordinance Office organised Operation Backfire which, in October 1945, assembled enough V-2 missiles and supporting components to enable the launch of three (possibly four, depending on source consulted) of them from a site near Cuxhaven in northern Germany. Although these launches were inclined and the rockets didn't achieve the altitude necessary to be regarded as sub-orbital spaceflight, the Backfire report remains the most extensive technical documentation of the rocket, including all support procedures, tailored vehicles and fuel composition.

Subsequently, the British Interplanetary Society proposed an enlarged man-carrying version of the V-2 called Megaroc. The plan, written in 1946, envisaged a three-year development programme culminating in the launch of test pilot Eric Brown on a sub-orbital mission in 1949.

The decision by the Ministry of Supply under Attlee's government to concentrate on research into nuclear power generation and sub-sonic passenger jet aircraft over supersonic atmospheric flight and spaceflight delayed the introduction of both of the latter, although only by a year in the case of supersonic flight, as the data from the Miles M.52 was handed to Bell Aircraft.

Space Race

Over a decade after the Megaroc proposal, true orbital space flight, both uncrewed and crewed, was developed by the Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War, in a competition dubbed the Space Race.

First artificial satellite

The race began in 1957, when both the US and the USSR made statements announcing they planned to launch artificial satellites during the 18 month long International Geophysical Year of July 1957 to December 1958. On July 29, 1957, the US announced a planned launch of the Vanguard by the spring of 1958, and on July 31, the USSR announced it would launch a satellite in the fall of 1957.

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite of Earth in the history of mankind.

On November 3, 1957, the Soviet Union launched the second satellite, Sputnik 2, and the first to carry a living animal, a dog named Laika. Sputnik 3 was launched on May 15, 1958, and carried a large array of instruments for geophysical research and provided data on pressure and composition of the upper atmosphere, concentration of charged particles, photons in cosmic rays, heavy nuclei in cosmic rays, magnetic and electrostatic fields, and meteoric particles.

After a series of failures with the program, the US succeeded with Explorer 1, which became the first US satellite in space, on February 1, 1958. This carried scientific instrumentation and detected the theorized Van Allen radiation belt.

The US public shock over Sputnik 1 became known as the Sputnik crisis. On July 29, 1958, the US Congress passed legislation turning the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) into the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) with responsibility for the nation's civilian space programs. In 1959, NASA began Project Mercury to launch single-man capsules into Earth orbit and chose a corps of seven astronauts introduced as the Mercury Seven.

First man in space

On April 12, 1961, the USSR opened the era of crewed spaceflight, with the flight of the first cosmonaut (Russian name for space travelers), Yuri Gagarin. Gagarin's flight, part of the Soviet Vostok space exploration program, took 108 minutes and consisted of a single orbit of the Earth.

On August 7, 1961, Gherman Titov, another Soviet cosmonaut, became the second man in orbit during his Vostok 2 mission.

By June 16, 1963, the Union launched a total of six Vostok cosmonauts, two pairs of them flying concurrently, and accumulating a total of 260 cosmonaut-orbits and just over sixteen cosmonaut-days in space.

On May 5, 1961, the US launched its first suborbital Mercury astronaut, Alan Shepard, in the Freedom 7 capsule. Unlike Gagarin, Shepard manually controlled his spacecraft's attitude and landed inside it thus technically making Freedom 7 the first complete human spaceflight by FAI definitions. The US public was becoming increasingly shocked and alarmed at the widening lead obtained by the USSR, so President John F. Kennedy announced on May 25 a plan to land a man on the Moon by 1970, launching the three-man Apollo program.

On February 20, 1962, the US succeeded in launching the third crewed orbital spaceflight in history, with John Glenn, the first US orbital astronaut, making three orbits during his Friendship 7 mission. By May 16, 1963, the US launched a total of six Project Mercury astronauts, logging a cumulative 34 Earth orbits, and 51 hours in space.

First woman in space

The first woman in space was former civilian parachutist Valentina Tereshkova, who entered orbit on June 16, 1963, aboard the Soviet mission Vostok 6. The chief Soviet spacecraft designer, Sergey Korolyov, conceived of the idea to recruit a female cosmonaut corps and launch two women concurrently on Vostok 5/6. However, his plan was changed to launch a male first in Vostok 5, followed shortly afterward by Tereshkova. The then first secretary of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, spoke to Tereshkova by radio during her flight.

On November 3, 1963, Tereshkova married fellow cosmonaut Andrian Nikolayev, who had previously flown on Vostok 3. On June 8, 1964, she gave birth to the first child conceived by two space travelers. The couple divorced in 1982, and Tereshkova went on to become a prominent member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

The second woman to fly to space was aviator Svetlana Savitskaya, aboard Soyuz T-7 on August 18, 1982.

Sally Ride became the first American woman in space when she flew aboard Space Shuttle mission STS-7 on June 18, 1983. Women space travelers went on to become commonplace during the 1980s.

Helen Sharman became the first European woman in space aboard the Soyuz TM-12 on May 18, 1991.

Competition develops

Khrushchev pressured Korolyov to quickly produce greater space achievements in competition with the announced Gemini and Apollo plans. Rather than allowing him to develop his plans for a crewed Soyuz spacecraft, he was forced to make modifications to squeeze two or three men into the Vostok capsule, calling the result Voskhod. Only two of these were launched. Voskhod 1 was the first spacecraft with a crew of three, who could not wear space suits because of size and weight constrictions. Alexei Leonov made the first spacewalk when he left the Voskhod 2 on March 8, 1965. He was almost lost in space when he had extreme difficulty fitting his inflated space suit back into the cabin through an airlock, and a landing error forced him and his crewmate to be lost in dangerous woods for hours before being found by the recovery crew.

The start of crewed Gemini missions was delayed a year later than NASA had planned, but ten largely successful missions were launched in 1965 and 1966, allowing the US to overtake the Soviet lead by achieving space rendezvous (Gemini 6A) and docking (Gemini 8) of two vehicles, long duration flights of eight days (Gemini 5) and fourteen days (Gemini 7), and demonstrating the use of extra-vehicular activity to do useful work outside a spacecraft (Gemini 12).

The USSR made no crewed flights during this period but continued to develop its Soyuz craft and secretly accepted Kennedy's implicit lunar challenge, designing Soyuz variants for lunar orbit and landing. They also attempted to develop the N1, a large, crewed Moon-capable launch vehicle similar to the US Saturn V.

As both nations rushed to get their new spacecraft flying with men, the intensity of the competition caught up to them in early 1967, when they suffered their first crew fatalities. On January 27, the entire crew of Apollo 1, "Gus" Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee, were killed by suffocation in a fire that swept through their cabin during a ground test approximately one month before their planned launch. On April 24, the single pilot of Soyuz 1, Vladimir Komarov, was killed in a crash when his landing parachutes tangled, after a mission cut short by electrical and control system problems. Both accidents were determined to be caused by design defects in the spacecraft, which were corrected before crewed flights resumed.

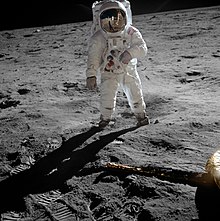

The US conducted the first crewed spaceflight to leave earth orbit and orbit the Moon on December 21, 1968 with the Apollo 8 space mission. Later on they succeeded in achieving President Kennedy's goal on July 20, 1969, with the landing of Apollo 11. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first men to set foot on the Moon. Six such successful landings were achieved through 1972, with one failure on Apollo 13.

The N1 rocket suffered four catastrophic uncrewed launch failures between 1969 and 1972, and the Soviet government officially discontinued its crewed lunar program on June 24, 1974, when Valentin Glushko succeeded Korolyov as General Spacecraft Designer.

Both nations went on to fly relatively small, non-permanent crewed space laboratories Salyut and Skylab, using their Soyuz and Apollo craft as shuttles. The US launched only one Skylab, but the USSR launched a total of seven "Salyuts", three of which were secretly Almaz military crewed reconnaissance stations, which carried "defensive" cannons. Crewed reconnaissance stations were found to be a bad idea since uncrewed satellites could do the job much more cost-effectively. The United States Air Force had planned a crewed reconnaissance station, the Manned Orbital Laboratory, which was cancelled in 1969. The Soviets cancelled Almaz in 1978.

In a season of detente, the two competitors declared an end to the race and shook hands (literally) on July 17, 1975, with the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, where the two craft docked, and the crews exchanged visits.

Programs

United States

Until the 21st century, space programs of the United States were exclusively operated by government agencies. Since 21st century, several aerospace companies are trying to dominate the space industry, with SpaceX being the most successful spaceflight company of all time.

NASA

- NASA is an independent agency that is not a part of any executive department, but reports directly to the President.

Project Mercury

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. Its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Union. John Glenn became the first American to orbit the earth on February 20, 1962 aboard the Mercury-Atlas 6.

Project Gemini

Project Gemini was NASA's second human spaceflight program. The program ran from 1961 to 1966. The program pioneered the orbital maneuvers required for space rendezvous. Ed White became the first American to make an extravehicular activity (EVA, or "space walk"), on June 3, 1965, during Gemini 4. Gemini 6A and 7 accomplished the first space rendezvous on December 15, 1965. Gemini 8 achieved the first space docking with an uncrewed Agena Target Vehicle on March 16, 1966. Gemini 8 was also the first US spacecraft to experience in-space critical failure endangering the lives of the crew.

Apollo program

The Apollo program was the third human spaceflight program carried out by NASA. The programs goal was to orbit and land crewed vehicles on the Moon. The program ran from 1969 to 1972. Apollo 8 was the first human spaceflight to leave earth orbit and orbit the Moon on December 21, 1968. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first men to set foot on the Moon during the Apollo 11 mission on July 20, 1969.

Skylab

The Skylab program's goal was to create the first space station of NASA. The program marked the last launch of the Saturn V rocket on May 19, 1973. Many experiments were performed on board, including unprecedented solar studies. The longest crewed mission of the program was Skylab 4 which lasted 84 days, from November 16, 1973 to February 8, 1974. The total mission duration was 2249 days, with Skylab finally falling from orbit over Australia on July 11, 1979.

Space Shuttle

Although its pace slowed, space exploration continued after the end of the Space Race. The United States launched the first reusable spacecraft, the Space Shuttle, on the 20th anniversary of Gagarin's flight, April 12, 1981. On November 15, 1988, the Soviet Union duplicated this with an uncrewed flight of the only Buran-class shuttle to fly, its first and only reusable spacecraft. It was never used again after the first flight; instead the Soviet Union continued to develop space stations using the Soyuz craft as the crew shuttle.

Sally Ride became the first American woman in space in 1983. Eileen Collins was the first female Shuttle pilot, and with Shuttle mission STS-93 in July 1999 she became the first woman to command a US spacecraft.

The United States continued missions to the ISS and other goals with the high-cost Shuttle system, which was retired in 2011.

Soviet Union

Sputnik

The Sputnik 1 became the first artificial Earth satellite on 4 October 1957. The satellite transmitted a radio signal, but had no sensors otherwise. Studying the Sputnik 1 allowed scientists to calculate the drag from the upper atmosphere by measuring position and speed of the satellite. Sputnik 1 broadcast for 21 days until its batteries depleted on 4 October 1957, and the satellite finally fell from orbit on 4 January 1958.

Luna programme

The Luna programme was a series of uncrewed robotic satellite launches with the goal of studying the Moon.The program ran from 1959 to 1976 and consisted of 15 successful missions, the program achieved many first achievements and collected data on the Moon's chemical composition, gravity, temperature, and radiation. Luna 2 became the first man made object to make contact with the Moon's surface in September 1959. Luna 3 returned the first photographs of the far side of the moon in October 1959.

Vostok

The Vostok Programme the first Soviet spaceflight project to put the Soviet citizens into low Earth orbit and return them safely. The programme carried out six crewed spaceflights between 1961 and 1963. The program was the first program to put humans into space, with Yuri Gagarin becoming the first man in space on April 12, 1961 aboard the Vostok 1. Gherman Titov Became the first person to stay in orbit for a full day on August 7, 1961 aboard the vostok 2. Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space on June 16, 1963 aboard the Vostok 6.

Voskhod

The Voskhod programme began in 1964 and consisted of two crewed flights before the program was canceled by the Soyuz programme in 1966. Voskhod 1 launched on October 12, 1964 and was the first crewed spaceflight with a multi-crewed vehicle. Alexei Leonov performed the first spacewalk aboard Voskhod 2 on March 18, 1965.

Salyut

The Salyut programme was the first space station program undertaken by the Soviet Union. The goal was to carry out long-term research into the problems of living in space and a variety of astronomical, biological and Earth-resources experiments. The program ran from 1971 to 1986. Salyut 1, the first station in the program, became the world's first crewed space station.

Soyuz programme

The Soyuz programme was initiated by the soviet space program in the 1960s and continues as the responsibility of roscosmos to this day. The program currently consists of 140 completed flights, and since the retirement of the US Space Shuttle has been the only craft to transport humans. The programs original goal was part of a program to put a cosmonaut on the moon, and later became crucial to the construction of the Mir space station.

Mir

Mir (Russian: Мир, IPA: [ˈmʲir]; lit. 'peace' or 'world') was a space station that operated in low Earth orbit from 1986 to 2001, operated by the Soviet Union and later by Russia. Mir was the first modular space station and was assembled in orbit from 1986 to 1996. It had a greater mass than any previous spacecraft. At the time it was the largest artificial satellite in orbit, succeeded by the International Space Station (ISS) after Mir's orbit decayed. The station served as a microgravity research laboratory in which crews conducted experiments in biology, human biology, physics, astronomy, meteorology, and spacecraft systems with a goal of developing technologies required for permanent occupation of space.

Mir was the first continuously inhabited long-term research station in orbit and held the record for the longest continuous human presence in space at 3,644 days, until it was surpassed by the ISS on 23 October 2010. It holds the record for the longest single human spaceflight, with Valeri Polyakov spending 437 days and 18 hours on the station between 1994 and 1995. Mir was occupied for a total of twelve and a half years out of its fifteen-year lifespan, having the capacity to support a resident crew of three, or larger crews for short visits.International Space Station

Recent space exploration has proceeded, to some extent in worldwide cooperation, the high point of which was the construction and operation of the International Space Station (ISS). At the same time, the international space race between smaller space powers since the end of the 20th century can be considered the foundation and expansion of markets of commercial rocket launches and space tourism.

The United States continued other space exploration, including major participation with the ISS with its own modules. It also planned a set of uncrewed Mars probes, military satellites, and more. The Constellation program, began by President George W. Bush in 2005, aimed to launch the Orion spacecraft by 2018. A subsequent return to the Moon by 2020 was to be followed by crewed flights to Mars, but the program was canceled in 2010 in favor of encouraging commercial US human launch capabilities.

Russia, a successor to the Soviet Union, has high potential but smaller funding. Its own space programs, some of a military nature, perform several functions. They offer a wide commercial launch service while continuing to support the ISS with several of their own modules. They also operate crewed and cargo spacecraft which continued after the US Shuttle program ended. They are developing a new multi-function Orel spacecraft for use in 2020 and have plans to perform human moon missions as well.

European Space Agency

The European Space Agency has taken the lead in commercial uncrewed launches since the introduction of the Ariane 4 in 1988 but is in competition with NASA, Russia, Sea Launch (private), China, India, and others. The ESA-designed crewed shuttle Hermes and space station Columbus were under development in the late 1980s in Europe; however, these projects were canceled, and Europe did not become the third major "space power".

The European Space Agency has launched various satellites, has utilized the crewed Spacelab module aboard US shuttles, and has sent probes to comets and Mars. It also participates in ISS with its own module and the uncrewed cargo spacecraft ATV.

Currently ESA has a program for development of an independent multi-function crewed spacecraft CSTS scheduled for completion in 2018. Further goals include an ambitious plan called the Aurora Programme, which intends to send a human mission to Mars soon after 2030. A set of various landmark missions to reach this goal are currently under consideration. The ESA has a multi-lateral partnership and plans for spacecraft and further missions with foreign participation and co-funding. ESA is also developing Galileo program which seeks to give independence to the EU from the American GPS.

China

Since 1956 the Chinese have had a space program which was aided early on from 1957-1960 by the Soviets. They were provided missile technology experts and missiles to study from. In 1965 plans were made to launch a human into space by 1979, and in 1967 the plans were made for a 4-human spacecraft. "East is Red" was launched on April 24, 1970 and was the first satellite to be launched by the Chinese. In 1974 the plan for human spaceflight was scrapped when policy makers decided that applications satellites were more important and competing with the US and USSR wasn't as important. In late 1986, the 863 Project was started which had a focus on military applications, but also had a goal for human spaceflight.

Despite possessing less funding than ESA or NASA, the People's Republic of China has achieved crewed space flight and operates a commercial satellite launch service. There are plans for a Chinese space station and a program to send uncrewed probes to Mars.

China's first attempt at a crewed spacecraft, Shuguang, was abandoned after years of development, but on October 15, 2003, China became the third nation to develop an indigenous human spaceflight capability when Yang Liwei entered orbit aboard Shenzhou 5.

The US Pentagon released a report in 2006, detailing concerns about China's growing presence in space, including its capability for military action. In 2007 China tested a ballistic missile designed to destroy satellites in orbit, which was followed by a US demonstration of a similar capability in 2008.

France

Emmanuel Macron announced on 13 July 2019 the project to create a military command specialising in space, which would be based in Toulouse.

This command should be operational in September 2020 within the Air Force to become the Air and Space Force. Its purpose will be to strengthen France's space power in order to defend its satellites and deepen its knowledge of space. It will also aim to compete with other nations in this new place of strategic confrontation.

Japan

Japan's space agency, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, is a major space player in Asia. While not maintaining a commercial launch service, Japan has deployed a module in the ISS and operates an uncrewed cargo spacecraft, the H-II Transfer Vehicle.

JAXA has plans to launch a Mars fly-by probe. Their lunar probe, SELENE, is touted as the most sophisticated lunar exploration mission in the post-Apollo era. Japan's Hayabusa probe was mankind's first sample return from an asteroid. IKAROS was the first operational solar sail.

Although Japan developed the HOPE-X, Kankoh-maru, and Fuji crewed capsule spacecraft, none of them have been launched. Japan's current ambition is to deploy a new crewed spacecraft by 2025 and to establish a Moon base by 2030.

Taiwan

The National Space Organization (NSPO; formerly known as the National Space Program Office) and the National Chung-Shan Institute of Science and Technology are the national civilian space agencies of the democratic industrialized developed country of Taiwan under the auspices of the Ministry of Science and Technology (Taiwan). The National Chung-Shan Institute of Science and Technology is involved in designing and building Taiwanese nuclear weapons, hypersonic missiles, spacecraft and rockets for launching satellites while the National Space Organization is involved in space exploration, satellite construction, and satellite development as well as related technologies and infrastructure (including the FORMOSAT series of Earth observation satellites similar to NASA along with DARPA {In-Q-Tel} such as Google Earth {Keyhole, Inc} or so forth) and related research in astronautics, quantum physics, materials science with microgravity, aerospace engineering, remote sensing, astrophysics, atmospheric science, information science, design and construction of indigenous Taiwanese satellites and spacecraft, launching satellites and space probes into low Earth orbit. Additionally, a state of the art crewed spaceflight program is currently in development in Taiwan and is designed to compete directly with the crewed programs of China, United States and Russia. Active research is currently undergoing in the development and deployment of space-based weapons for the defense of national security in Taiwan.

India

ISRO

Indian Space Research Organisation, India's national space agency, maintains an active space program. It operates a small commercial launch service and launched a successful uncrewed lunar mission dubbed Chandrayaan-1 in October 2007. India has successfully launched an interplanetary mission, Mars Orbiter Mission, in 2013 which reached Mars in September 2014, hence becoming the first country in the world to do a Mars mission in its maiden attempt. On July 22, 2019, India sent Chandrayaan-2 to the Moon, whose Vikram lander crashed on the lunar south pole region on September 6.

Other nations

Cosmonauts and astronauts from other nations have flown in space, beginning with the flight of Vladimir Remek, a Czech, on a Soviet spacecraft on March 2, 1978. As of November 6, 2013, a total of 536 people from 38 countries have gone into space according to the FAI guideline.

Private Companies

SpaceX (USA)

Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (SpaceX) is an American aerospace manufacturer and space transportation services company headquartered in Hawthorne, California. SpaceX was founded in 2002 by Elon Musk with the goal of reducing space transportation costs to enable the colonization of Mars. SpaceX manufactures the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launch vehicles, several rocket engines, Dragon cargo and crew spacecraft and Starlink communications satellites.

SpaceX's achievements include the first privately funded liquid-propellant rocket to reach orbit (Falcon 1 in 2008), the first private company to successfully launch, orbit, and recover a spacecraft (Dragon in 2010), the first private company to send a spacecraft to the International Space Station (Dragon in 2012), the first vertical take-off and vertical propulsive landing for an orbital rocket (Falcon 9 in 2015), the first reuse of an orbital rocket (Falcon 9 in 2017), and the first private company to send astronauts to orbit and to the International Space Station (SpaceX Crew Dragon Demo-2 in 2020). SpaceX has flown and reflown the Falcon 9 series of rockets over one hundred times.Blue Origin

Blue Origin made the first reusable space capable rocket booster, New Shepard (it is suborbital, Falcon 9 was the first orbital). They also originally had the idea of landing rocket boosters on ships at sea, however SpaceX replicated their idea and did it first. They lead the national team, which is designing a lunar lander and transfer vehicle (Integrated Lander Vehicle). They will contribute by modifying their Blue Moon lunar lander.

Bigelow Aerospace

Bigelow Aerospace made the first commercial module in space (BEAM). They also designed and manufactured the first inflatable habitats in space (Genesis I and Genesis II). They also plan to make the first commercial space station around the moon (Lunar Depot), perhaps the first ever.

Northrop Grumman

They make commercial resupply runs to the ISS with their Cygnus spacecraft. They also helped develop non-commercial spacecraft during the space race (Apollo LM as Grumman). They also are a part of the national team, lead by Blue Origin which is designing a lunar lander and transfer vehicle (Integrated Lander Vehicle), partly based off of Cygnus.