| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nontheistic_religion |

Nontheistic religions are traditions of thought within a religious context—some otherwise aligned with theism, others not—in which nontheism informs religious beliefs or practices. Nontheism has been applied and plays significant roles in Progressivism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. While many approaches to religion exclude nontheism by definition, some inclusive definitions of religion show how religious practice and belief do not depend on the presence of (a) god(s). For example, Paul James and Peter Mandaville distinguish between religion and spirituality, but provide a definition of the term that avoids the usual reduction to "religions of the book":

Religion can be defined as a relatively-bounded system of beliefs, symbols and practices that addresses the nature of existence, and in which communion with others and Otherness is lived as if it both takes in and spiritually transcends socially-grounded ontologies of time, space, embodiment and knowing.

Buddhism

Existence of gods

The Buddha said that devas (translated as "gods") do exist, but they were regarded as still being trapped in samsara, and are not necessarily wiser than humans. In fact, the Buddha is often portrayed as a teacher of the gods, and superior to them.

Since the time of the Buddha, the denial of the existence of a creator deity has been seen as a key point in distinguishing Buddhist from non-Buddhist views. The question of an independent creator deity was answered by the Buddha in the Brahmajala Sutta. The Buddha denounced the view of a creator and sees that such notions are related to the false view of eternalism, and like the 61 other views, this belief causes suffering when one is attached to it and states these views may lead to desire, aversion and delusion. At the end of the Sutta the Buddha says he knows these 62 views and he also knows the truth that surpasses them. Later Buddhist philosophers also extensively criticized the idea of an eternal creator deity concerned with humanity.

Metaphysical questions

On one occasion, when presented with a problem of metaphysics by the monk Malunkyaputta, the Buddha responded with the Parable of the Poisoned Arrow. When a man is shot with an arrow thickly smeared with poison, his family summons a doctor to have the poison removed, and the doctor gives an antidote:

But the man refuses to let the doctor do anything before certain questions can be answered. The wounded man demands to know who shot the arrow, what his caste and job is, and why he shot him. He wants to know what kind of bow the man used and how he acquired the ingredients used in preparing the poison. Malunkyaputta, such a man will die before getting the answers to his questions. It is no different for one who follows the Way. I teach only those things necessary to realize the Way. Things which are not helpful or necessary, I do not teach.

Christianity

A few liberal Christian theologians define a "nontheistic God" as "the ground of all being" rather than as a personal divine being.

Many of them owe much of their theology to the work of Christian existentialist philosopher Paul Tillich, including the phrase "the ground of all being". Another quotation from Tillich is, "God does not exist. He is being itself beyond essence and existence. Therefore to argue that God exists is to deny him." This Tillich quotation summarizes his conception of God. He does not think of God as a being that exists in time and space, because that constrains God, and makes God finite. But all beings are finite, and if God is the Creator of all beings, God cannot logically be finite since a finite being cannot be the sustainer of an infinite variety of finite things. Thus God is considered beyond being, above finitude and limitation, the power or essence of being itself.

From a nontheistic, naturalist, and rationalist perspective, the concept of divine grace appears to be the same concept as luck.

Nontheist Quakers

A nontheist Friend or an atheist Quaker is someone who affiliates with, identifies with, engages in and/or affirms Quaker practices and processes, but who does not accept a belief in a theistic understanding of God, a Supreme Being, the divine, the soul or the supernatural. Like theistic Friends, nontheist Friends are actively interested in realizing centered peace, simplicity, integrity, community, equality, love, happiness and social justice in the Society of Friends and beyond.

Hinduism

Hinduism is characterised by extremely diverse beliefs and practices. In the words of R.C. Zaehner, "it is perfectly possible to be a good Hindu whether one's personal views incline toward monism, monotheism, polytheism, or even atheism." He goes on to say that it is a religion that neither depends on the existence or non-existence of God or Gods. More broadly, Hinduism can be seen as having three more important strands: one featuring a personal Creator or Divine Being, second that emphasises an impersonal Absolute and a third that is pluralistic and non-absolute. The latter two traditions can be seen as nontheistic.

Although the Vedas are broadly concerned with the completion of ritual, there are some elements that can be interpreted as either nontheistic or precursors to the later developments of the nontheistic tradition. The oldest Hindu scripture, the Rig Veda mentions that 'There is only one god though the sages may give it various names' (1.164.46). Max Müller termed this henotheism, and it can be seen as indicating one, non-dual divine reality, with little emphasis on personality. The famous Nasadiya Sukta, the 129th Hymn of the tenth and final Mandala (or chapter) of the Rig Veda, considers creation and asks "The gods came afterwards, with the creation of this universe. /Who then knows whence it has arisen?". This can be seen to contain the intuition that there must be a single principle behind all phenomena: 'That one' (tad ekam), self-sufficient, to which distinctions cannot be applied.

It is with the Upanishads, reckoned to be written in the first millennia (coeval with the ritualistic Brahmanas), that the Vedic emphasis on ritual was challenged. The Upanishads can be seen as the expression of new sources of power in India. Also, separate from the Upanishadic tradition were bands of wandering ascetics called Vadins whose largely nontheistic notions rejected the notion that religious knowledge was the property of the Brahmins. Many of these were shramanas, who represented a non-Vedic tradition rooted in India's pre-Aryan history. The emphasis of the Upanishads turned to knowledge, specifically the ultimate identity of all phenomena. This is expressed in the notion of Brahman, the key idea of the Upanishads, and much later philosophizing has been taken up with deciding whether Brahman is personal or impersonal. The understanding of the nature of Brahman as impersonal is based in the definition of it as 'ekam eva advitiyam' (Chandogya Upanishad 6.2.1) – it is one without a second and to which no substantive predicates can be attached. Further, both the Chandogya and Brihadaranyaka Upanishads assert that the individual atman and the impersonal Brahman are one. The mahāvākya statement Tat Tvam Asi, found in the Chandogya Upanishad, can be taken to indicate this unity. The latter Upanishad uses the negative term Neti neti to 'describe' the divine.

Classical Samkhya, Mimamsa, early Vaisheshika and early Nyaya schools of Hinduism do not accept the notion of an omnipotent creator God at all. While the Sankhya and Mimamsa schools no longer have significant followings in India, they are both influential in the development of later schools of philosophy. The Yoga of Patanjali is the school that probably owes most to the Samkhya thought. This school is dualistic, in the sense that there is a division between 'spirit' (Sanskrit: purusha) and 'nature' (Sanskrit: prakṛti). It holds Samadhi or 'concentrative union' as its ultimate goal and it does not consider God's existence as either essential or necessary to achieving this.

The Bhagavad Gita, contains passages that bear a monistic reading and others that bear a theistic reading. Generally, the book as a whole has been interpreted by some who see it as containing a primarily nontheistic message, and by others who stress its theistic message. These broadly either follow after either Sankara or Ramanuja An example of a nontheistic passage might be "The supreme Brahman is without any beginning. That is called neither being nor non-being," which Sankara interpreted to mean that Brahman can only be talked of in terms of negation of all attributes—'Neti neti'.

The Advaita Vedanta of Gaudapada and Sankara rejects theism as a consequence of its insistence that Brahman is "Without attributes, indivisible, subtle, inconceivable, and without blemish, Brahman is one and without a second. There is nothing other than He." This means that it lacks properties usually associated with God such as omniscience, perfect goodness, omnipotence, and additionally is identical with the whole of reality, rather than being a causal agent or ruler of it.

Jainism

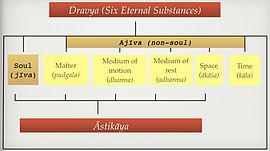

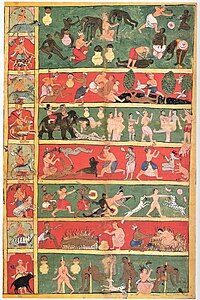

Jain texts claim that the universe consists of jiva (life force or souls) and ajiva (lifeless objects). According to Jain doctrine, the universe and its constituents-soul, matter, space, time, and principles of motion-have always existed. The universe and the matter and souls within it are eternal and uncreated, and there is no omnipotent creator god. Jainism offers an elaborate cosmology, including heavenly beings/devas, but these heavenly beings are not viewed as creators-they are subject to suffering and change like all other living beings, and are portrayed as mortal.

According to the Jain concept of divinity, any soul who destroys its karmas and desires, achieves liberation/Nirvana. A soul who destroys all its passions and desires has no desire to interfere in the working of the universe. If godliness is defined as the state of having freed one's soul from karmas and the attainment of enlightenment/Nirvana and a god as one who exists in such a state, then those who have achieved such a state can be termed gods (Tirthankara).

Besides scriptural authority, Jains also employ syllogism and deductive reasoning to refute creationist theories. Various views on divinity and the universe held by the Vedics, Sāmkhyas, Mimamsas, Buddhists, and other school of thoughts were criticized by Jain Ācāryas, such as Jinasena in Mahāpurāna.

Others

Philosophical models not falling within established religious structures, such as Daoism, Confucianism, Epicureanism, Deism, and Pandeism, have also been considered to be nontheistic religions.

The Satanic Temple, a sect of modern or rational Satanism, was officially recognized as a nontheistic religion in the United States on 25 April 2019.

The white supremacist Creativity movement has also been described as a nontheistic religion.