In philosophy and certain models of psychology, qualia (/ˈkwɑːliə/ or /ˈkweɪliə/; singular form: quale) are defined as individual instances of subjective, conscious experience. The term qualia derives from the Latin neuter plural form (qualia) of the Latin adjective quālis (Latin pronunciation: [ˈkʷaːlɪs]) meaning "of what sort" or "of what kind" in a specific instance, such as "what it is like to taste a specific apple, this particular apple now".

Examples of qualia include the perceived sensation of pain of a headache, the taste of wine, as well as the redness of an evening sky. As qualitative characters of sensation, qualia stand in contrast to "propositional attitudes", where the focus is on beliefs about experience rather than what it is directly like to be experiencing.

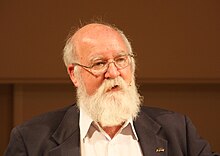

Philosopher and cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett once suggested that qualia was "an unfamiliar term for something that could not be more familiar to each of us: the ways things seem to us".

Much of the debate over their importance hinges on the definition of the term, and various philosophers emphasize or deny the existence of certain features of qualia. Consequently, the nature and existence of various definitions of qualia remain controversial because they are not verifiable.

Definitions

There are many definitions of qualia, which have changed over time. One of the simpler, broader definitions is: "The 'what it is like' character of mental states. The way it feels to have mental states such as pain, seeing red, smelling a rose, etc."

C.S. Peirce introduced the term quale in philosophy in 1866 (Writings, Chronological Edition, Vol. 1, pp. 477-8). C.I. Lewis (1929), was the first to use the term "qualia" in its generally agreed upon modern sense.

There are recognizable qualitative characters of the given, which may be repeated in different experiences, and are thus a sort of universals; I call these "qualia." But although such qualia are universals, in the sense of being recognized from one to another experience, they must be distinguished from the properties of objects. Confusion of these two is characteristic of many historical conceptions, as well as of current essence-theories. The quale is directly intuited, given, and is not the subject of any possible error because it is purely subjective.

Frank Jackson later defined qualia as "...certain features of the bodily sensations especially, but also of certain perceptual experiences, which no amount of purely physical information includes".

Daniel Dennett identifies four properties that are commonly ascribed to qualia. According to these, qualia are:

- ineffable – they cannot be communicated, or apprehended by any means other than direct experience.

- intrinsic – they are non-relational properties, which do not change depending on the experience's relation to other things.

- private – all interpersonal comparisons of qualia are systematically impossible.

- directly or immediately apprehensible by consciousness – to experience a quale is to know one experiences a quale, and to know all there is to know about that quale.

If qualia of this sort exist, then a normally sighted person who sees red would be unable to describe the experience of this perception in such a way that a listener who has never experienced color will be able to know everything there is to know about that experience. Though it is possible to make an analogy, such as "red looks hot", or to provide a description of the conditions under which the experience occurs, such as "it's the color you see when light of 700-nm wavelength is directed at you", supporters of this kind of qualia contend that such a description is incapable of providing a complete description of the experience.

Another way of defining qualia is as "raw feels". A raw feel is a perception in and of itself, considered entirely in isolation from any effect it might have on behavior and behavioral disposition. In contrast, a cooked feel is that perception seen as existing in terms of its effects. For example, the perception of the taste of wine is an ineffable, raw feel, while the experience of warmth or bitterness caused by that taste of wine would be a cooked feel. Cooked feels are not qualia.

According to an argument put forth by Saul Kripke in his paper "Identity and Necessity" (1971), one key consequence of the claim that such things as raw feels can be meaningfully discussed – that qualia exist – is that it leads to the logical possibility of two entities exhibiting identical behavior in all ways despite one of them entirely lacking qualia. While very few ever claim that such an entity, called a philosophical zombie, actually exists, the mere possibility is claimed to be sufficient to refute physicalism.

Arguably, the idea of hedonistic utilitarianism, where the ethical value of things is determined from the amount of subjective pleasure or pain they cause, is dependent on the existence of qualia.

Arguments for the existence

Since it is by definition impossible to convey qualia verbally, it is also impossible to demonstrate them directly in an argument; so a more tangential approach is needed. Arguments for qualia generally come in the form of thought experiments designed to lead one to the conclusion that qualia exist.

"What's it like to be?" argument

Although it does not actually mention the word "qualia", Thomas Nagel's paper "What is it like to be a bat?" is often cited in debates over qualia. Nagel argues that consciousness has an essentially subjective character, a what-it-is-like aspect. He states that "an organism has conscious mental states if and only if there is something that it is like to be that organism – something it is like for the organism." Nagel also suggests that the subjective aspect of the mind may not ever be sufficiently accounted for by the objective methods of reductionistic science. He claims that "if we acknowledge that a physical theory of mind must account for the subjective character of experience, we must admit that no presently available conception gives us a clue about how this could be done." Furthermore, he states that "it seems unlikely that any physical theory of mind can be contemplated until more thought has been given to the general problem of subjective and objective."

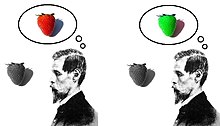

Inverted spectrum argument

The inverted spectrum thought experiment, originally developed by John Locke, invites us to imagine that we wake up one morning and find that for some unknown reason all the colors in the world have been inverted, i.e. swapped to the hue on the opposite side of a color wheel. Furthermore, we discover that no physical changes have occurred in our brains or bodies that would explain this phenomenon. Supporters of the existence of qualia argue that since we can imagine this happening without contradiction, it follows that we are imagining a change in a property that determines the way things look to us, but that has no physical basis. In more detail:

- Metaphysical identity holds of necessity.

- If something is possibly false, it is not necessary.

- It is conceivable that qualia could have a different relationship to physical brain-states.

- If it is conceivable, then it is possible.

- Since it is possible for qualia to have a different relationship with physical brain-states, they cannot be identical to brain states (by 1).

- Therefore, qualia are non-physical.

The argument thus claims that if we find the inverted spectrum plausible, we must admit that qualia exist (and are non-physical). Some philosophers find it absurd that an armchair argument can prove something to exist, and the detailed argument does involve a lot of assumptions about conceivability and possibility, which are open to criticism. Perhaps it is not possible for a given brain state to produce anything other than a given quale in our universe, and that is all that matters.

The idea that an inverted spectrum would be undetectable in practice is also open to criticism on more scientific grounds (see main article). There is an actual experiment – albeit somewhat obscure – that parallels the inverted spectrum argument. George M. Stratton, professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, performed an experiment in which he wore special prism glasses that caused the external world to appear upside down. After a few days of continually wearing the glasses, an adaptation occurred and the external world appeared righted. When the glasses were removed, perception of the external world again returned to the "normal" perceptual state. If this argument provides indicia that qualia exist, it does not necessarily follow that they must be non-physical, because that distinction should be considered a separate epistemological issue.

Zombie argument

A similar argument holds that it is conceivable (or not inconceivable) that there could be physical duplicates of people, called "philosophical zombies", without any qualia at all. These "zombies" would demonstrate outward behavior precisely similar to that of a normal human, but would not have a subjective phenomenology. It is worth noting that a necessary condition for the possibility of philosophical zombies is that there be no specific part or parts of the brain that directly give rise to qualia: The zombie can only exist if subjective consciousness is causally separate from the physical brain.

Are zombies possible? They're not just possible, they're actual. We're all zombies: Nobody is conscious. — D.C. Dennett (1992)

Explanatory gap argument

Joseph Levine's paper Conceivability, Identity, and the Explanatory Gap takes up where the criticisms of conceivability arguments, such as the inverted spectrum argument and the zombie argument, leave off. Levine agrees that conceivability is flawed as a means of establishing metaphysical realities, but points out that even if we come to the metaphysical conclusion that qualia are physical, there is still an explanatory problem.

While I think this materialist response is right in the end, it does not suffice to put the mind-body problem to rest. Even if conceivability considerations do not establish that the mind is in fact distinct from the body, or that mental properties are metaphysically irreducible to physical properties, still they do demonstrate that we lack an explanation of the mental in terms of the physical.

However, such an epistemological or explanatory problem might indicate an underlying metaphysical issue – the non-physicality of qualia, even if not proven by conceivability arguments is far from ruled out.

In the end, we are right back where we started. The explanatory gap argument doesn't demonstrate a gap in nature, but a gap in our understanding of nature. Of course a plausible explanation for there being a gap in our understanding of nature is that there is a genuine gap in nature. But so long as we have countervailing reasons for doubting the latter, we have to look elsewhere for an explanation of the former.

Knowledge argument

F.C. Jackson offers what he calls the "knowledge argument" for qualia. One example runs as follows:

Mary the color scientist knows all the physical facts about color, including every physical fact about the experience of color in other people, from the behavior a particular color is likely to elicit to the specific sequence of neurological firings that register that a color has been seen. However, she has been confined from birth to a room that is black and white, and is only allowed to observe the outside world through a black and white monitor. When she is allowed to leave the room, it must be admitted that she learns something about the color red the first time she sees it – specifically, she learns what it is like to see that color.

This thought experiment has two purposes. First, it is intended to show that qualia exist. If one accepts the thought experiment, we believe that Mary gains something after she leaves the room – that she acquires knowledge of a particular thing that she did not possess before. That knowledge, Jackson argues, is knowledge of the quale that corresponds to the experience of seeing red, and it must thus be conceded that qualia are real properties, since there is a difference between a person who has access to a particular quale and one who does not.

The second purpose of this argument is to refute the physicalist account of the mind. Specifically, the knowledge argument is an attack on the physicalist claim about the completeness of physical truths. The challenge posed to physicalism by the knowledge argument runs as follows:

- Before her release, Mary was in possession of all the physical information about color experiences of other people.

- After her release, Mary learns something about the color experiences of other people.

Therefore, - Before her release, Mary was not in possession of all the

information about other people's color experiences, even though she was

in possession of all the physical information.

Therefore, - There are truths about other people's color experience that are not physical.

Therefore, - Physicalism is false.

First Jackson argued that qualia are epiphenomenal: not causally efficacious with respect to the physical world. Jackson does not give a positive justification for this claim – rather, he seems to assert it simply because it defends qualia against the classic problem of dualism. Our natural assumption would be that qualia must be causally efficacious in the physical world, but some would ask how we could argue for their existence if they did not affect our brains. If qualia are to be non-physical properties (which they must be in order to constitute an argument against physicalism), some argue that it is almost impossible to imagine how they could have a causal effect on the physical world. By redefining qualia as epiphenomenal, Jackson attempts to protect them from the demand of playing a causal role.

Later, however, he rejected epiphenomenalism. This, he argues, is because when Mary first sees red, she says "wow", so it must be Mary's qualia that cause her to say "wow". This contradicts epiphenomenalism. Since the Mary's room thought experiment seems to create this contradiction, there must be something wrong with it. This is often referred to as the "there must be a reply" reply.

Critics of qualia

Daniel Dennett

In Consciousness Explained (1991) and "Quining Qualia" (1988), Dennett offers an argument against qualia by claiming that the above definition breaks down when one tries to make a practical application of it. In a series of thought experiments, which he calls "intuition pumps", he brings qualia into the world of neurosurgery, clinical psychology, and psychological experimentation. His argument states that, once the concept of qualia is so imported, it turns out that we can either make no use of it in the situation in question, or that the questions posed by the introduction of qualia are unanswerable precisely because of the special properties defined for qualia.

In Dennett's updated version of the inverted spectrum thought experiment, "alternative neurosurgery", you again awake to find that your qualia have been inverted – grass appears red, the sky appears orange, etc. According to the original account, you should be immediately aware that something has gone horribly wrong. Dennett argues, however, that it is impossible to know whether the diabolical neurosurgeons have indeed inverted your qualia (by tampering with your optic nerve, say), or have simply inverted your connection to memories of past qualia. Since both operations would produce the same result, you would have no means on your own to tell which operation has actually been conducted, and you are thus in the odd position of not knowing whether there has been a change in your "immediately apprehensible" qualia.

Dennett's argument revolves around the central objection that, for qualia to be taken seriously as a component of experience – for them to even make sense as a discrete concept – it must be possible to show that

- (a) it is possible to know that a change in qualia has occurred, as opposed to a change in something else; or that

- (b) there is a difference between having a change in qualia and not having one.

Dennett attempts to show that we cannot satisfy (a) either through introspection or through observation, and that qualia's very definition undermines its chances of satisfying (b).

Supporters of qualia could point out that in order for you to notice a change in qualia, you must compare your current qualia with your memories of past qualia. Arguably, such a comparison would involve immediate apprehension of your current qualia and your memories of past qualia, but not the past qualia themselves. Furthermore, modern functional brain imaging has increasingly suggested that the memory of an experience is processed in similar ways and in similar zones of the brain as those originally involved in the original perception. This may mean that there would be asymmetry in outcomes between altering the mechanism of perception of qualia and altering their memories. If the diabolical neurosurgery altered the immediate perception of qualia, you might not even notice the inversion directly, since the brain zones which re-process the memories would themselves invert the qualia remembered. On the other hand, alteration of the qualia memories themselves would be processed without inversion, and thus you would perceive them as an inversion. Thus, you might know immediately if memory of your qualia had been altered, but might not know if immediate qualia were inverted or whether the diabolical neurosurgeons had done a sham procedure.

Dennett also has a response to the "Mary the color scientist" thought experiment. He argues that Mary would not, in fact, learn something new if she stepped out of her black and white room to see the color red. Dennett asserts that if she already truly knew "everything about color", that knowledge would include a deep understanding of why and how human neurology causes us to sense the "quale" of color. Mary would therefore already know exactly what to expect of seeing red, before ever leaving the room. Dennett argues that the misleading aspect of the story is that Mary is supposed to not merely be knowledgeable about color but to actually know all the physical facts about it, which would be a knowledge so deep that it exceeds what can be imagined, and twists our intuitions.

If Mary really does know everything physical there is to know about the experience of color, then this effectively grants her almost omniscient powers of knowledge. Using this, she will be able to deduce her own reaction, and figure out exactly what the experience of seeing red will feel like.

Dennett finds that many people find it difficult to see this, so he uses the case of RoboMary to further illustrate what it would be like for Mary to possess such a vast knowledge of the physical workings of the human brain and color vision. RoboMary is an intelligent robot who, instead of the ordinary color camera-eyes, has a software lock such that she is only able to perceive black and white and shades in-between.

RoboMary can examine the computer brain of similar non-color-locked robots when they look at a red tomato, and see exactly how they react and what kinds of impulses occur. RoboMary can also construct a simulation of her own brain, unlock the simulation's color-lock and, with reference to the other robots, simulate exactly how this simulation of herself reacts to seeing a red tomato. RoboMary naturally has control over all of her internal states except for the color-lock. With the knowledge of her simulation's internal states upon seeing a red tomato, RoboMary can put her own internal states directly into the states they would be in upon seeing a red tomato. In this way, without ever seeing a red tomato through her cameras, she will know exactly what it is like to see a red tomato.

Dennett uses this example as attempt to show us that Mary's all-encompassing physical knowledge makes her own internal states as transparent as those of a robot or computer, and it is almost straightforward for her to figure out exactly how it feels to see red.

Perhaps Mary's failure to learn exactly what seeing red feels like is simply a failure of language, or a failure of our ability to describe experiences. An alien race with a different method of communication or description might be perfectly able to teach their version of Mary exactly how seeing the color red would feel. Perhaps it is simply a uniquely human failing to communicate first-person experiences from a third-person perspective. Dennett suggests that the description might even be possible using English. He uses a simpler version of the Mary thought experiment to show how this might work. What if Mary was in a room without triangles and was prevented from seeing or making any triangles? An English-language description of just a few words would be sufficient for her to imagine what it is like to see a triangle – she can simply and directly visualize a triangle in her mind. Similarly, Dennett proposes, it is perfectly, logically possible that the quale of what it is like to see red could eventually be described in an English-language description of millions or billions of words.

In "Are we explaining consciousness yet?" (2001), Dennett approves of an account of qualia defined as the deep, rich collection of individual neural responses that are too fine-grained for language to capture. For instance, a person might have an alarming reaction to yellow because of a yellow car that hit her previously, and someone else might have a nostalgic reaction to a comfort food. These effects are too individual-specific to be captured by English words. "If one dubs this inevitable residue qualia, then qualia are guaranteed to exist, but they are just more of the same, dispositional properties that have not yet been entered in the catalog [...]."

Paul Churchland

According to Paul Churchland, Mary might be considered to be like a feral child. Feral children have suffered extreme isolation during childhood. Technically when Mary leaves the room, she would not have the ability to see or know what the color red is. A brain has to learn and develop how to see colors. Patterns need to form in the V4 section of the visual cortex. These patterns are formed from exposure to wavelengths of light. This exposure is needed during the early stages of brain development. In Mary's case, the identifications and categorizations of color will only be in respect to representations of black and white.

Gary Drescher

In his book Good and Real (2006), Gary Drescher compares qualia with "gensyms" (generated symbols) in Common Lisp. These are objects that Lisp treats as having no properties or components and which can only be identified as equal or not equal to other objects. Drescher explains, "we have no introspective access to whatever internal properties make the red gensym recognizably distinct from the green [...] even though we know the sensation when we experience it." Under this interpretation of qualia, Drescher responds to the Mary thought experiment by noting that "knowing about red-related cognitive structures and the dispositions they engender – even if that knowledge were implausibly detailed and exhaustive – would not necessarily give someone who lacks prior color-experience the slightest clue whether the card now being shown is of the color called red." This does not, however, imply that our experience of red is non-mechanical; "on the contrary, gensyms are a routine feature of computer-programming languages".

David Lewis

D.K. Lewis has an argument that introduces a new hypothesis about types of knowledge and their transmission in qualia cases. Lewis agrees that Mary cannot learn what red looks like through her monochrome physicalist studies. But he proposes that this doesn't matter. Learning transmits information, but experiencing qualia doesn't transmit information; instead it communicates abilities. When Mary sees red, she doesn't get any new information. She gains new abilities – now she can remember what red looks like, imagine what other red things might look like and recognize further instances of redness.

Lewis states that Jackson's thought experiment uses the phenomenal information hypothesis – that is, the new knowledge that Mary gains upon seeing red is phenomenal information. Lewis then proposes a different ability hypothesis that differentiates between two types of knowledge: knowledge "that" (information) and knowledge "how" (abilities). Normally the two are entangled; ordinary learning is also an experience of the subject concerned, and people both learn information (for instance, that Freud was a psychologist) and gain ability (to recognize images of Freud). However, in the thought experiment, Mary can only use ordinary learning to gain know-that knowledge. She is prevented from using experience to gain the know-how knowledge that would allow her to remember, imagine and recognize the color red.

We have the intuition that Mary has been deprived of some vital data to do with the experience of redness. It is also uncontroversial that some things cannot be learned inside the room; for example, we do not expect Mary to learn how to ski within the room. Lewis has articulated that information and ability are potentially different things. In this way, physicalism is still compatible with the conclusion that Mary gains new knowledge. It is also useful for considering other instances of qualia; "being a bat" is an ability, so it is know-how knowledge.

Marvin Minsky

The artificial intelligence researcher Marvin Minsky thinks the problems posed by qualia are essentially issues of complexity, or rather of mistaking complexity for simplicity.

Now, a philosophical dualist might then complain: "You've described how hurting affects your mind – but you still can't express how hurting feels." This, I maintain, is a huge mistake – that attempt to reify "feeling" as an independent entity, with an essence that's indescribable. As I see it, feelings are not strange alien things. It is precisely those cognitive changes themselves that constitute what "hurting" is – and this also includes all those clumsy attempts to represent and summarize those changes. The big mistake comes from looking for some single, simple, "essence" of hurting, rather than recognizing that this is the word we use for complex rearrangement of our disposition of resources.

Michael Tye

Michael Tye holds the opinion there are no qualia, no "veils of perception" between us and the referents of our thought. He describes our experience of an object in the world as "transparent". By this he means that no matter what private understandings and/or misunderstandings we may have of some public entity, it is still there before us in reality. The idea that qualia intervene between ourselves and their origins he regards as "a massive error"; as he says, "it is just not credible that visual experiences are systematically misleading in this way"; "the only objects of which you are aware are the external ones making up the scene before your eyes"; there are "no such things as the qualities of experiences" for "they are qualities of external surfaces (and volumes and films) if they are qualities of anything." This insistence permits him to take our experience as having a reliable base since there is no fear of losing contact with the realness of public objects.

In Tye's thought there is no question of qualia without information being contained within them; it is always "an awareness that", always "representational". He characterizes the perception of children as a misperception of referents that are undoubtedly as present for them as they are for grown-ups. As he puts it, they may not know that "the house is dilapidated", but there is no doubt about their seeing the house. After-images are dismissed as presenting no problem for the Transparency Theory because, as he puts it, after-images being illusory, there is nothing that one sees.

Tye proposes that phenomenal experience has five basic elements, for which he has coined the acronym PANIC – Poised, Abstract, Nonconceptual, Intentional Content. It is "Poised" in the sense that the phenomenal experience is always presented to the understanding, whether or not the agent is able to apply a concept to it. Tye adds that the experience is "maplike" in that, in most cases, it reaches through to the distribution of shapes, edges, volumes, etc. in the world – you may not be reading the "map" but, as with an actual map there is a reliable match with what it is mapping. It is "Abstract" because it is still an open question in a particular case whether you are in touch with a concrete object (someone may feel a pain in a "left leg" when that leg has actually been amputated). It is "Nonconceptual" because a phenomenon can exist although one does not have the concept by which to recognize it. Nevertheless, it is "Intentional" in the sense that it represents something, again whether or not the particular observer is taking advantage of that fact; this is why Tye calls his theory "representationalism". This last makes it plain that Tye believes that he has retained a direct contact with what produces the phenomena and is therefore not hampered by any trace of a "veil of perception".

Roger Scruton

Roger Scruton, whilst sceptical of the idea that neurobiology can tell us a great amount about consciousness, is of the opinion that the idea of qualia is incoherent, and that Wittgenstein's famous private language argument effectively disproves it. Scruton writes,

The belief that these essentially private features of mental states exist, and that they form the introspectible essence of whatever possesses them, is grounded in a confusion, one that Wittgenstein tried to sweep away in his arguments against the possibility of a private language. When you judge that I am in pain, it is on the basis of my circumstances and behavior, and you could be wrong. When I ascribe a pain to myself, I don’t use any such evidence. I don’t find out that I am in pain by observation, nor can I be wrong. But that is not because there is some other fact about my pain, accessible only to me, which I consult in order to establish what I am feeling. For if there were this inner private quality, I could misperceive it; I could get it wrong, and I would have to find out whether I am in pain. To describe my inner state, I would also have to invent a language, intelligible only to me – and that, Wittgenstein plausibly argues, is impossible. The conclusion to draw is that I ascribe pain to myself not on the basis of some inner quale but on no basis at all.

In his book On Human Nature, Scruton does pose a potential line of criticism to this, which is that whilst Wittgenstein's private language argument does disprove the concept of reference to qualia, or the idea that we can talk even to ourselves of their nature, it does not disprove its existence altogether. Scruton believes that this is a valid criticism, and this is why he stops short of actually saying that qualia don't exist, and instead merely suggests that we should abandon them as a concept. However, he does give a quote by Wittgenstein as a response: "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent."

Proponents of qualia

David Chalmers

David Chalmers formulated the hard problem of consciousness, raising the issue of qualia to a new level of importance and acceptance in the field. In Chalmers (1995) he also argued for what he called "the principle of organizational invariance". In this paper, he argues that if a system such as one of appropriately configured computer chips reproduces the functional organization of the brain, it will also reproduce the qualia associated with the brain.

E. J. Lowe

E.J. Lowe, of Durham University, denies that holding to indirect realism (in which we have access only to sensory features internal to the brain) necessarily implies a Cartesian dualism. He agrees with Bertrand Russell that our "retinal images" – that is, the distributions across our retinas – are connected to "patterns of neural activity in the cortex" (Lowe, 1996). He defends a version of the causal theory of perception in which a causal path can be traced between the external object and the perception of it. He is careful to deny that we do any inferring from the sensory field, a view which he believes allows us to found an access to knowledge on that causal connection. In a later work he moves closer to the non-epistemic theory in that he postulates "a wholly non-conceptual component of perceptual experience", but he refrains from analyzing the relation between the perceptual and the "non-conceptual". Most recently he has drawn attention to the problems that hallucination raises for the direct realist and to their disinclination to enter the discussion on the topic.

J. B. Maund

John Barry Maund, an Australian philosopher of perception at the University of Western Australia, draws attention to a key distinction of qualia. Qualia are open to being described on two levels, a fact that he refers to as "dual coding". Using the Television Analogy (which, as the non-epistemic argument shows, can be shorn of its objectionable aspects), he points out that, if asked what we see on a television screen there are two answers that we might give:

The states of the screen during a football match are unquestionably different from those of the screen during a chess game, but there is no way available to us of describing the ways in which they are different except by reference to the play, moves and pieces in each game.

He has refined the explanation by shifting to the example of a "Movitype" screen, often used for advertisements and announcements in public places. A Movitype screen consists of a matrix – or "raster" as the neuroscientists prefer to call it (from the Latin rastrum, a "rake"; think of the lines on a TV screen as "raked" across) – that is made up of an array of tiny light-sources. A computer-led input can excite these lights so as to give the impression of letters passing from right to left, or even, on the more advanced forms now commonly used in advertisements, to show moving pictures. Maund's point is as follows. It is obvious that there are two ways of describing what you are seeing. We could either adopt the everyday public language and say "I saw some sentences, followed by a picture of a 7-Up can." Although that is a perfectly adequate way of describing the sight, nevertheless, there is a scientific way of describing it which bears no relation whatsoever to this commonsense description. One could ask the electronics engineer to provide us with a computer print-out staged across the seconds that you were watching it of the point-states of the raster of lights. This would no doubt be a long and complex document, with the state of each tiny light-source given its place in the sequence. The interesting aspect of this list is that, although it would give a comprehensive and point-by-point-detailed description of the state of the screen, nowhere in that list would there be a mention of "English sentences" or "a 7-Up can".

What this makes clear is that there are two ways to describe such a screen, (1) the "commonsense" one, in which publicly recognizable objects are mentioned, and (2) an accurate point-by-point account of the actual state of the field, but makes no mention of what any passer-by would or would not make of it. This second description would be non-epistemic from the common sense point of view, since no objects are mentioned in the print-out, but perfectly acceptable from the engineer's point of view. Note that, if one carries this analysis across to human sensing and perceiving, this rules out Dennett's claim that all qualiaphiles must regard qualia as "ineffable", for at this second level they are in principle quite "effable" – indeed, it is not ruled out that some neurophysiologist of the future might be able to describe the neural detail of qualia at this level.

Maund has also extended his argument particularly with reference of color. Color he sees as a dispositional property, not an objective one, an approach which allows for the facts of difference between person and person, and also leaves aside the claim that external objects are colored. Colors are therefore "virtual properties", in that it is as if things possessed them; although the naïve view attributes them to objects, they are intrinsic, non-relational inner experiences.

Moreland Perkins

In his book Sensing the World, Moreland Perkins argues that qualia need not be identified with their objective sources: a smell, for instance, bears no direct resemblance to the molecular shape that gives rise to it, nor is a toothache actually in the tooth. He is also like Hobbes in being able to view the process of sensing as being something complete in itself; as he puts it, it is not like "kicking a football" where an external object is required – it is more like "kicking a kick", an explanation which entirely avoids the familiar Homunculus Objection, as adhered to, for example, by Gilbert Ryle. Ryle was quite unable even to entertain this possibility, protesting that "in effect it explained the having of sensations as the not having of sensations." However, A.J. Ayer in a rejoinder identified this objection as "very weak" as it betrayed an inability to detach the notion of eyes, indeed any sensory organ, from the neural sensory experience.

Ramachandran and Hirstein

Vilayanur S. Ramachandran and William Hirstein proposed three laws of qualia (with a fourth later added), which are "functional criteria that need to be fulfilled in order for certain neural events to be associated with qualia" by philosophers of the mind:

- Qualia are irrevocable and indubitable. You don't say 'maybe it is red but I can visualize it as green if I want to'. An explicit neural representation of red is created that invariably and automatically 'reports' this to higher brain centres.

- Once the representation is created, what can be done with it is open-ended. You have the luxury of choice, e.g., if you have the percept of an apple you can use it to tempt Adam, to keep the doctor away, bake a pie, or just to eat. Even though the representation at the input level is immutable and automatic, the output is potentially infinite. This isn't true for, say, a spinal reflex arc where the output is also inevitable and automatic. Indeed, a paraplegic can even have an erection and ejaculate without an orgasm.

- Short-term memory. The input invariably creates a representation that persists in short-term memory – long enough to allow time for choice of output. Without this component, again, you get just a reflex arc.

- Attention. Qualia and attention are closely linked. You need attention to fulfill criterion number two; to choose. A study of circuits involved in attention, therefore, will shed much light on the riddle of qualia.

They proposed that the phenomenal nature of qualia could be communicated (as in "oh that is what salt tastes like") if brains could be appropriately connected with a "cable of neurons". If this turned out to be possible this would scientifically prove or objectively demonstrate the existence and the nature of qualia.

Howard Robinson and William Robinson

Howard Robinson is a philosopher who has concentrated his research within the philosophy of mind. Taking what has been through the latter part of the last century an unfashionable stance, he has consistently argued against those explanations of sensory experience that would reduce them to physical origins. He has never regarded the theory of sense-data as refuted, but has set out to refute in turn the objections which so many have considered to be conclusive. The version of the theory of sense-data he defends takes what is before consciousness in perception to be qualia as mental presentations that are causally linked to external entities, but which are not physical in themselves. Unlike the philosophers so far mentioned, he is therefore a dualist, one who takes both matter and mind to have real and metaphysically distinct natures. In one of his articles he takes the physicalist to task for ignoring the fact that sensory experience can be entirely free of representational character. He cites phosphenes as a stubborn example (phosphenes are flashes of neural light that result either from sudden pressure in the brain – as induced, for example, by intense coughing, or through direct physical pressure on the retina), and points out that it is grossly counter-intuitive to argue that these are not visual experiences on a par with open-eye seeing.

William Robinson (no relation) takes a very similar view to that of his namesake. In his book, Understanding Phenomenal Consciousness, he is unusual as a dualist in calling for research programs that investigate the relation of qualia to the brain. The problem is so stubborn, he says, that too many philosophers would prefer "to explain it away", but he would rather have it explained and does not see why the effort should not be made. However, he does not expect there to be a straightforward scientific reduction of phenomenal experience to neural architecture; on the contrary he regards this as a forlorn hope. The "Qualitative Event Realism" that Robinson espouses sees phenomenal consciousness as caused by brain events but not identical with them, being non-material events.

It is noteworthy that he refuses to set aside the vividness – and commonness – of mental images, both visual and aural, standing here in direct opposition to Daniel Dennett, who has difficulty in crediting the experience in others. He is similar to Moreland Perkins in keeping his investigation wide enough to apply to all the senses.

Edmond Wright

Edmond Wright is a philosopher who considers the inter-subjective aspect of perception. From Locke onwards it had been normal to frame perception problems in terms of a single subject S looking at a single entity E with a property p. However, if we begin with the facts of the differences in sensory registration from person to person, coupled with the differences in the criteria we have learned for distinguishing what we together call "the same" things, then a problem arises of how two persons align their differences on these two levels so that they can still get a practical overlap on parts of the real about them – and, in particular, update each other about them.

Wright mentions being struck with the hearing difference between himself and his son, discovering that his son could hear sounds up to nearly 20 kilohertz while his range only reached to 14 kHz or so. This implies that a difference in qualia could emerge in human action (for example, the son could warn the father of a high-pitched escape of a dangerous gas kept under pressure, the sound-waves of which would be producing no qualia evidence at all for the father). The relevance for language thus becomes critical, for an informative statement can best be understood as an updating of a perception – and this may involve a radical re-selection from the qualia fields viewed as non-epistemic, even perhaps of the presumed singularity of "the" referent, a fortiori if that "referent" is the self. Here he distinguishes his view from that of Revonsuo, who too readily makes his "virtual space" "egocentric".

Wright's particular emphasis has been on what he asserts is a core feature of communication, that, in order for an updating to be set up and made possible, both speaker and hearer have to behave as if they have identified "the same singular thing", which, he notes, partakes of the structure of a joke or a story. Wright says that this systematic ambiguity seems to opponents of qualia to be a sign of fallacy in the argument (as ambiguity is in pure logic) whereas, on the contrary, it is sign – in talk about "what" is perceived – of something those speaking to each other have to learn to take advantage of. In extending this analysis, he has been led to argue for an important feature of human communication being the degree and character of the faith maintained by the participants in the dialogue, a faith that has priority over what has before been taken to be the key virtues of language, such as "sincerity", "truth", and "objectivity". Indeed, he considers that to prioritize them over faith is to move into superstition.

Erwin Schrödinger

Erwin Schrödinger, a theoretical physicist and one of the leading pioneers of quantum mechanics, also published in the areas of colorimetry and color perception. In several of his philosophical writings, he defends the notion that qualia are not physical.

The sensation of colour cannot be accounted for by the physicist's objective picture of light-waves. Could the physiologist account for it, if he had fuller knowledge than he has of the processes in the retina and the nervous processes set up by them in the optical nerve bundles and in the brain? I do not think so.

He continues on to remark that subjective experiences do not form a one-to-one correspondence with stimuli. For example, light of wavelength in the neighborhood of 590 nm produces the sensation of yellow, whereas exactly the same sensation is produced by mixing red light, with wavelength 760 nm, with green light, at 535 nm. From this he concludes that there is no "numerical connection with these physical, objective characteristics of the waves" and the sensations they produce.

Schrödinger concludes with a proposal of how it is that we might arrive at the mistaken belief that a satisfactory theoretical account of qualitative experience has been – or might ever be – achieved:

Scientific theories serve to facilitate the survey of our observations and experimental findings. Every scientist knows how difficult it is to remember a moderately extended group of facts, before at least some primitive theoretical picture about them has been shaped. It is therefore small wonder, and by no means to be blamed on the authors of original papers or of text-books, that after a reasonably coherent theory has been formed, they do not describe the bare facts they have found or wish to convey to the reader, but clothe them in the terminology of that theory or theories. This procedure, while very useful for our remembering the fact in a well-ordered pattern, tends to obliterate the distinction between the actual observations and the theory arisen from them. And since the former always are of some sensual quality, theories are easily thought to account for sensual qualities; which, of course, they never do.

Neurobiological blending of perspectives

Rodolfo Llinás

When looked at philosophically, qualia become a tipping point between physicality and the metaphysical, which polarizes the discussion, as we've seen above, into "Do they or do they not exist?" and "Are they physical or beyond the physical?" However, from a strictly neurological perspective, they can both exist, and be very important to the organism's survival, and be the result of strict neuronal oscillation, and still not rule out the metaphysical. A good example of this pro/con blending is given by Llinás (2002), who argues that qualia are ancient and necessary for an organism's survival and a product of neuronal oscillation. Llinás gives the evidence of anesthesia of the brain and subsequent stimulation of limbs to demonstrate that qualia can be "turned off" with changing only the variable of neuronal oscillation (local brain electrical activity), while all other connections remain intact, arguing strongly for an oscillatory – electrical origin of qualia, or important aspects of them.

Roger Orpwood

Roger Orpwood, an engineer with a strong background in studying neural mechanisms, proposed a neurobiological model that gives rise to qualia and ultimately, consciousness. As advancements in cognitive and computational neuroscience continue to grow, the need to study the mind, and qualia, from a scientific perspective follows. Orpwood does not deny the existence of qualia, nor does he intend to debate its physical or non-physical existence. Rather, he suggests that qualia are created through the neurobiological mechanism of re-entrant feedback in cortical systems.

Orpwood develops his mechanism by first addressing the issue of information. One unsolved aspect of qualia is the concept of the fundamental information involved in creating the experience. He does not address a position on the metaphysics of the information underlying the experience of qualia, nor does he state what information actually is. However, Orpwood does suggest that information in general is of two types: the information structure and information message. Information structures are defined by the physical vehicles and structural, biological patterns encoding information. That encoded information is the information message; a source describing what that information is. The neural mechanism or network receives input information structures, completes a designated instructional task (firing of the neuron or network), and outputs a modified information structure to downstream regions. The information message is the purpose and meaning of the information structure and causally exists as a result of that particular information structure. Modification of the information structure changes the meaning of the information message, but the message itself cannot be directly altered.

Local cortical networks have the capacity to receive feedback from their own output information structures. This form of local feedback continuously cycles part of the networks output structures as its next input information structure. Since the output structure must represent the information message derived from the input structure, each consecutive cycle that is fed-back will represent the output structure the network just generated. As the network of mechanisms cannot recognize the information message, but only the input information structure, the network is unaware that it is representing its own previous outputs. The neural mechanisms are merely completing their instructional tasks and outputting any recognizable information structures. Orpwood proposes that these local networks come into an attractor state that consistently outputs exactly the same information structure as the input structure. Instead of only representing the information message derived from the input structure, the network will now represent its own output and thereby its own information message. As the input structures are fed-back, the network identifies the previous information structure as being a previous representation of the information message. As Orpwood writes:

Once an attractor state has been established, the output [of a network] is a representation of its own identity to the network.

Representation of the networks own output structures, by which represents its own information message, is Orpwood's explanation that grounds the manifestation of qualia via neurobiological mechanisms. These mechanisms are particular to networks of pyramidal neurons. Although computational neuroscience still has much to investigate regarding pyramidal neurons, their complex circuitry is relatively unique. Research shows that the complexity of pyramidal neuron networks is directly related to the increase in the functional capabilities of a species. When human pyramidal networks are compared with other primate species and species with less intricate behavioral and social interactions, the complexity of these neural networks drastically decline. The complexity of these networks are also increased in frontal brain regions. These regions are often associated with conscious assessment and modification of one's immediate environment; often referred to as executive functions.

Sensory input is necessary to gain information from the environment, and perception of that input is necessary for navigating and modifying interactions with the environment. This suggests that frontal regions containing more complex pyramidal networks are associated with an increased perceptive capacity. As perception is necessary for conscious thought to occur, and since the experience of qualia is derived from consciously recognizing some perception, qualia may indeed be specific to the functional capacity of pyramidal networks. This derives Orpwood's notion that the mechanisms of re-entrant feedback may not only create qualia, but also be the foundation to consciousness.

Other issues

Indeterminacy

It is possible to apply a criticism similar to Nietzsche's criticism of Kant's "thing in itself" to qualia: Qualia are unobservable in others and unquantifiable in us. We cannot possibly be sure, when discussing individual qualia, that we are even discussing the same phenomena. Thus, any discussion of them is of indeterminate value, as descriptions of qualia are necessarily of indeterminate accuracy.

Qualia can be compared to "things in themselves" in that they have no publicly demonstrable properties; this, along with the impossibility of being sure that we are communicating about the same qualia, makes them of indeterminate value and definition in any philosophy in which proof relies upon precise definition. On the other hand, qualia could be considered akin to Kantian phenomena since they are held to be seemings of appearances. Revonsuo, however, considers that, within neurophysiological inquiry, a definition at the level of the fields may become possible (just as we can define a television picture at the level of liquid crystal pixels).

Causal efficacy

Whether or not qualia or consciousness can play any causal role in the physical world remains an open question, with epiphenomenalism acknowledging the existence of qualia while denying it any causal power. The position has been criticized by a number of philosophers, if only because our own consciousness seem to be causally active. In order to avoid epiphenomenalism, one who believes that qualia are nonphysical would need to embrace something like interactionist dualism; or perhaps emergentism, the claim that there are as yet unknown causal relations between the mental and physical. This in turn would imply that qualia can be detected by an external agency through their causal powers.

Epistemological issues

To illustrate: one might be tempted to give as examples of qualia "the pain of a headache, the taste of wine, or the redness of an evening sky". But this list of examples already prejudges a central issue in the current debate on qualia. An analogy might make this clearer. Suppose someone wants to know the nature of the liquid crystal pixels on a television screen, those tiny elements that provide all the distributions of color that go to make up the picture. It would not suffice as an answer to say that they are the "redness of an evening sky" as it appears on the screen. We would protest that their real character was being ignored. One can see that relying on the list above assumes that we must tie sensations not only to the notion of given objects in the world (the "head", "wine", "an evening sky"), but also to the properties with which we characterize the experiences themselves ("redness", for example).

Nor is it satisfactory to print a little red square as at the top of the article, for, since each person has a slightly different registration of the light-rays, it confusingly suggests that we all have the same response. Imagine in a television shop seeing "a red square" on twenty screens at once, each slightly different – something of vital importance would be overlooked if a single example were to be taken as defining them all.

Yet it has been argued whether or not identification with the external object should still be the core of a correct approach to sensation, for there are many who state the definition thus because they regard the link with external reality as crucial. If sensations are defined as "raw feels", there arises a palpable threat to the reliability of knowledge. The reason has been given that, if one sees them as neurophysiological happenings in the brain, it is difficult to understand how they could have any connection to entities, whether in the body or the external world. It has been declared, by John McDowell for example, that to countenance qualia as a "bare presence" prevents us ever gaining a certain ground for our knowledge. The issue is thus fundamentally an epistemological one: it would appear that access to knowledge is blocked if one allows the existence of qualia as fields in which only virtual constructs are before the mind.

His reason is that it puts the entities about which we require knowledge behind a "veil of perception", an occult field of "appearance" which leaves us ignorant of the reality presumed to be beyond it. He is convinced that such uncertainty propels into the dangerous regions of relativism and solipsism: relativism sees all truth as determined by the single observer; solipsism, in which the single observer is the only creator of and legislator for his or her own universe, carries the assumption that no one else exists. These accusations constitute a powerful ethical argument against qualia being something going on in the brain, and these implications are probably largely responsible for the fact that in the 20th century it was regarded as not only freakish, but also dangerously misguided to uphold the notion of sensations as going on inside the head. The argument was usually strengthened with mockery at the very idea of "redness" being in the brain: the question was – and still is – "How can there be red neurons in the brain?" which strikes one as a justifiable appeal to common sense.

To maintain a philosophical balance, the argument for "raw feels" needs to be set side by side with the claim above. Viewing sensations as "raw feels" implies that initially they have not yet – to carry on the metaphor – been "cooked", that is, unified into "things" and "persons", which is something the mind does after the sensation has responded to the blank input, that response driven by motivation, that is, initially by pain and pleasure, and subsequently, when memories have been implanted, by desire and fear. Such a "raw-feel" state has been more formally identified as "non-epistemic". In support of this view, the theorists cite a range of empirical facts. The following can be taken as representative.

- There are brain-damaged persons, known as "agnosics" (literally "not-knowing") who still have vivid visual sensations but are quite unable to identify any entity before them, including parts of their own body.

- There is also the similar predicament of persons, formerly blind, who are given sight for the first time – and consider what it is a newborn baby must experience.

A German physicist of the 19th century, Hermann von Helmholtz, proposed a simple experiment to demonstrate the non-epistemic nature of qualia: His instructions were to stand in front of a familiar landscape, turn your back on it, bend down and look at the landscape between your legs – you will find it difficult in the upside-down view to recognize what you found familiar before.

These examples suggest that a "bare presence" – that is, knowledgeless sensation that is no more than evidence – may really occur. Present supporters of the non-epistemic theory thus regard sensations as only data in the sense that they are "given" (Latin datum, "given") and fundamentally involuntary, which is a good reason for not regarding them as basically mental. In the last century they were called "sense-data" by the proponents of qualia, but this led to the confusion that they carried with them reliable proofs of objective causal origins. For instance, one supporter of qualia was happy to speak of the redness and bulginess of a cricket ball as a typical "sense-datum", though not all of them were happy to define qualia by their relation to external entities (see R.W. Sellars (1922)). The modern argument, following Sellars' lead, centers on how we learn under the regime of motivation to interpret the sensory evidence in terms of "things", "persons", and "selves" through a continuing process of feedback.

The definition of qualia thus is governed by one's point of view, and that inevitably brings with it philosophical and neurophysiological presuppositions. The question, therefore, of what qualia can be raises profound issues in the philosophy of mind, since some materialists want to deny their existence altogether: on the other hand, if they are accepted, they cannot be easily accounted for as they raise the difficult problem of consciousness. There are committed dualists such as Richard L. Amoroso or John Hagelin who believe that the mental and the material are two distinct aspects of physical reality like the distinction between the classical and quantum regimes. In contrast, there are direct realists for whom the thought of qualia is unscientific as there appears to be no way of making them fit within the modern scientific picture; and there are committed proselytizers for a final truth who reject them as forcing knowledge out of reach.