| Substance use disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Drug use disorder |

| |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

| Complications | Drug overdose |

Substance use disorder (SUD) is the persistent use of drugs (including alcohol) despite substantial harm and adverse consequences. Substance use disorders are characterized by an array of mental/emotional, physical, and behavioral problems such as chronic guilt; an inability to reduce or stop consuming the substance(s) despite repeated attempts; driving while intoxicated; and physiological withdrawal symptoms. Drug classes that are involved in SUD include: alcohol; cannabis; phencyclidine and other hallucinogens, such as arylcyclohexylamines; inhalants; opioids; sedatives, hypnotics, or anxiolytics; stimulants; tobacco; and other or unknown substances.

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (2013), also known as DSM-5, the DSM-IV diagnoses of substance abuse and substance dependence were merged into the category of substance use disorders. The severity of substance use disorders can vary widely; in the DSM-5 diagnosis of a SUD, the severity of an individual's SUD is qualified as mild, moderate, or severe on the basis of how many of the 11 diagnostic criteria are met. The International Classification of Diseases 11th revision (ICD-11) divides substance use disorders into two categories: (1) harmful pattern of substance use; and (2) substance dependence.

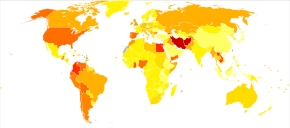

In 2017, globally 271 million people (5.5% of adults) were estimated to have used one or more illicit drugs. Of these, 35 million had a substance use disorder. An additional 237 million men and 46 million women have alcohol use disorder as of 2016. In 2017, substance use disorders from illicit substances directly resulted in 585,000 deaths. Direct deaths from drug use, other than alcohol, have increased over 60 percent from 2000 to 2015. Alcohol use resulted in an additional 3 million deaths in 2016.

Causes

This section divides substance use disorder causes into categories consistent with the biopsychosocial model. However, it is important to bear in mind that these categories are used by scientists partly for convenience; the categories often overlap (for example, adolescents and adults whose parents had (or have) an alcohol use disorder display higher rates of alcohol problems, a phenomenon that can be due to genetic, observational learning, socioeconomic, and other causal factors); and these categories are not the only ways to classify substance use disorder etiology.

Similarly, most researchers in this and related areas (such as the etiology of psychopathology generally), emphasize that various causal factors interact and influence each other in complex and multifaceted ways.

Social determinants

Among older adults, being divorced, separated, or single; having more financial resources; lack of religious affiliation; bereavement; involuntary retirement; and homelessness are all associated with alcohol problems, including alcohol use disorder.

Psychological determinants

Psychological causal factors include cognitive, affective, and developmental determinants, among others. For example, individuals who begin using alcohol or other drugs in their teens are more likely to have a substance use disorder as adults. Other common risk factors are being male, being under 25, having other mental health problems (with the latter two being related to symptomatic relapse, impaired clinical and psychosocial adjustment, reduced medication adherence, and lower response to treatment), and lack of familial support and supervision. (As mentioned above, some of these causal factors can also be categorized as social or biological). Other psychological risk factors include high impulsivity, sensation seeking, neuroticism and openness to experience in combination with low conscientiousness.

Biological determinants

Children born to parents with SUDs have roughly a two-fold increased risk in developing a SUD compared to children born to parents without any SUDs.

Diagnosis

| Addiction and dependence glossary | |

|---|---|

| |

Individuals whose drug or alcohol use cause significant impairment or distress may have a substance use disorder (SUD). Diagnosis usually involves an in-depth examination, typically by psychiatrist, psychologist, or drug and alcohol counselor. The most commonly used guidelines are published in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). There are 11 diagnostic criteria which can be broadly categorized into issues arising from substance use related to loss of control, strain to one's interpersonal life, hazardous use, and pharmacologic effects.

DSM-5 guidelines for the diagnosis of a substance use disorder require that the individual have significant impairment or distress from their pattern of drug use, and at least two of the symptoms listed below in a given year.

- Using more of a substance than planned, or using a substance for a longer interval than desired

- Inability to cut down despite desire to do so

- Spending substantial amount of the day obtaining, using, or recovering from substance use

- Cravings or intense urges to use

- Repeated usage causes or contributes to an inability to meet important social, or professional obligations

- Persistent usage despite user's knowledge that it is causing frequent problems at work, school, or home

- Giving up or cutting back on important social, professional, or leisure activities because of use

- Using in physically hazardous situations, or usage causing physical or mental harm

- Persistent use despite the user's awareness that the substance is causing or at least worsening a physical or mental problem

- Tolerance: needing to use increasing amounts of a substance to obtain its desired effects

- Withdrawal: characteristic group of physical effects or symptoms that emerge as amount of substance in the body decreases

There are additional qualifiers and exceptions outlined in the DSM. For instance, if an individual is taking opiates as prescribed, they may experience physiologic effects of tolerance and withdrawal, but this would not cause an individual to meet criteria for a SUD without additional symptoms also being present. A physician trained to evaluate and treat substance use disorders will take these nuances into account during a diagnostic evaluation.

Severity

Substance use disorders can range widely in severity, and there are numerous methods to monitor and qualify the severity of an individual's SUD. The DSM-5 includes specifiers for severity of a SUD. Individuals who meet only 2 or 3 criteria are often deemed to have mild SUD. Substance users who meet 4 or 5 criteria may have their SUD described as moderate, and persons meeting 6 or more criteria as severe. In the DSM-5, the term drug addiction is synonymous with severe substance use disorder. The quantity of criteria met offer a rough gauge on the severity of illness, but licensed professionals will also take into account a more holistic view when assessing severity which includes specific consequences and behavioral patterns related to an individual's substance use. They will also typically follow frequency of use over time, and assess for substance-specific consequences, such as the occurrence of blackouts, or arrests for driving under the influence of alcohol, when evaluating someone for an alcohol use disorder. There are additional qualifiers for stages of remission that are based on the amount of time an individual with a diagnosis of a SUD has not met any of the 11 criteria except craving. Some medical systems refer to an Addiction Severity Index to assess the severity of problems related to substance use. The index assesses potential problems in seven categories: medical, employment/support, alcohol, other drug use, legal, family/social, and psychiatric.

Screening tools

There are several different screening tools that have been validated for use with adolescents, such as the CRAFFT, and with adults, such as CAGE, AUDIT and DALI. Laboratory tests to detect alcohol and other drugs in urine and blood may be useful during the assessment process to confirm a diagnosis, to establish a baseline, and later, to monitor progress. However, since these tests measure recent substance use rather than chronic use or dependence, they are not recommended as screening tools.

Mechanisms

Management

Detoxification

Depending on the severity of use, and the given substance, early treatment of acute withdrawal may include medical detoxification. Of note, acute withdrawal from heavy alcohol use should be done under medical supervision to prevent a potentially deadly withdrawal syndrome known as delirium tremens. See also Alcohol detoxification.

Therapy

Therapists often classify people with chemical dependencies as either interested or not interested in changing. About 11% of Americans with substance use disorder seek treatment, and 40–60% of those people relapse within a year. Treatments usually involve planning for specific ways to avoid the addictive stimulus, and therapeutic interventions intended to help a client learn healthier ways to find satisfaction. Clinical leaders in recent years have attempted to tailor intervention approaches to specific influences that affect addictive behavior, using therapeutic interviews in an effort to discover factors that led a person to embrace unhealthy, addictive sources of pleasure or relief from pain.

| Treatments | ||

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral pattern | Intervention | Goals |

| Low self-esteem, anxiety, verbal hostility | Relationship therapy, client centered approach | Increase self-esteem, reduce hostility and anxiety |

| Defective personal constructs, ignorance of interpersonal means | Cognitive restructuring including directive and group therapies | Insight |

| Focal anxiety such as fear of crowds | Desensitization | Change response to same cue |

| Undesirable behaviors, lacking appropriate behaviors | Aversive conditioning, operant conditioning, counter conditioning | Eliminate or replace behavior |

| Lack of information | Provide information | Have client act on information |

| Difficult social circumstances | Organizational intervention, environmental manipulation, family counseling | Remove cause of social difficulty |

| Poor social performance, rigid interpersonal behavior | Sensitivity training, communication training, group therapy | Increase interpersonal repertoire, desensitization to group functioning |

| Grossly bizarre behavior | Medical referral | Protect from society, prepare for further treatment |

| Adapted from: Essentials of Clinical Dependency Counseling, Aspen Publishers | ||

From the applied behavior analysis literature and the behavioral psychology literature, several evidence-based intervention programs have emerged, such as behavioral marital therapy, community reinforcement approach, cue exposure therapy, and contingency management strategies. In addition, the same author suggests that social skills training adjunctive to inpatient treatment of alcohol dependence is probably efficacious.

Medication

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) refers to the combination of behavioral interventions and medications to treat substance use disorders. Certain medications can be useful in treating severe substance use disorders. In the United States five medications are approved to treat alcohol and opioid use disorders. There are no approved medications for cocaine, methamphetamine, or other substance use disorders as of 2002.

Medications, such as methadone and disulfiram, can be used as part of broader treatment plans to help a patient function comfortably without illicit opioids or alcohol. Medications can be used in treatment to lessen withdrawal symptoms. Evidence has demonstrated the efficacy of MAT at reducing illicit drug use and overdose deaths, improving retention in treatment, and reducing HIV transmission.

Epidemiology

Rates of substance use disorders vary by nation and by substance, but the overall prevalence is high. On a global level, men are affected at a much higher rate than women. Younger individuals are also more likely to be affected than older adults.

United States

In 2017, roughly 7% of Americans aged 12 or older had a SUD in the past year. Rates of alcohol use disorder in the past year were just over 5%. Approximately 3% of people aged 12 or older had an illicit drug use disorder. The highest rates of illicit drug use disorder were among those aged 18 to 25 years old, at roughly 7%.

There were over 72,000 deaths from drug overdose in the United States in 2017, which is a threefold increase from 2002. However the CDC calculates alcohol overdose deaths separately; thus, this 72,000 number does not include the 2,366 alcohol overdose deaths in 2017. Overdose fatalities from synthetic opioids, which typically involve fentanyl, have risen sharply in the past several years to contribute to nearly 30,000 deaths per year. Death rates from synthetic opioids like fentanyl have increased 22-fold in the period from 2002 to 2017. Heroin and other natural and semi-synthetic opioids combined to contribute to roughly 31,000 overdose fatalities. Cocaine contributed to roughly 15,000 overdose deaths, while methamphetamine and benzodiazepines each contributed to roughly 11,000 deaths. Of note, the mortality from each individual drug listed above cannot be summed because many of these deaths involved combinations of drugs, such as overdosing on a combination of cocaine and an opioid.

Deaths from alcohol consumption account for the loss of over 88,000 lives per year. Tobacco remains the leading cause of preventable death, responsible for greater than 480,000 deaths in the United States each year. These harms are significant financially with total costs of more than $420 billion annually and more than $120 billion in healthcare.

Canada

According to Statistics Canada (2018), approximately one in five Canadians aged 15 years and older experience a substance use disorder in their lifetime. In Ontario specifically, the disease burden of mental illness and addiction is 1.5 times higher than all cancers together and over 7 times that of all infectious diseases. Across the country, the ethnic group that is statistically the most impacted by substance use disorders compared to the general population are the Indigenous peoples of Canada. In a 2019 Canadian study, it was found that Indigenous participants experienced greater substance-related problems than non-Indigenous participants.

Statistics Canada's Canadian Community Health Survey (2012) shows that alcohol was the most common substance for which Canadians met the criteria for abuse or dependence. Surveys on Indigenous people in British Columbia show that around 75% of residents on reserve feel alcohol use is a problem in their community and 25% report they have a problem with alcohol use themselves. However, only 66% of First Nations adults living on reserve drink alcohol compared to 76% of the general population. Further, in an Ontario study on mental health and substance use among Indigenous people, 19% reported the use of cocaine and opiates, higher than the 13% of Canadians in the general population that reported using opioids.

Australia

Historical and ongoing colonial practices continue to impact the health of Indigenous Australians, with Indigenous populations being more susceptible to substance use and related harms. For example, alcohol and tobacco are the predominant substances used in Australia. Although tobacco smoking is declining in Australia, it remains disproportionately high in Indigenous Australians with 45% aged 18 and over being smokers, compared to 16% among non-Indigenous Australians in 2014–2015. As for alcohol, while proportionately more Indigenous people refrain from drinking than non-Indigenous people, Indigenous people who do consume alcohol are more likely to do so at high-risk levels. About 19% of Indigenous Australians qualified for risky alcohol consumption (defined as 11 or more standard drinks at least once a month), which is 2.8 times the rate that their non-Indigenous counterparts consumed the same level of alcohol.

However, while alcohol and tobacco usage are declining, use of other substances, such as cannabis and opiates, is increasing in Australia. Cannabis is the most widely used illicit drug in Australia, with cannabis usage being 1.9 times higher than non-Indigenous Australians. Prescription opioids have seen the greatest increase in usage in Australia, although use is still lower that in the US. In 2016, Indigenous persons were 2.3 times more likely to misuse pharmaceutical drugs than non-Indigenous people.