Ray Bradbury | |

|---|---|

| Born | Ray Douglas Bradbury August 22, 1920 Waukegan, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | June 5, 2012 (aged 91) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Westwood Memorial Park, Westwood, Los Angeles |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Education | Los Angeles High School |

| Period | 1938–2012 |

| Genre | Fantasy, science fiction, horror fiction, mystery fiction, magic realism |

| Notable works | |

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse | Marguerite McClure

(m. 1947; died 2003) |

| Children | 4 |

| Signature | |

| Website | |

| www | |

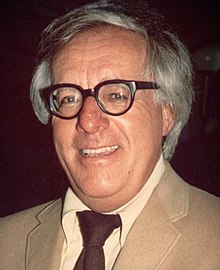

Ray Douglas Bradbury (/ˈbrædˌbɛri/; August 22, 1920 – June 5, 2012) was an American author and screenwriter. One of the most celebrated 20th-century American writers, he worked in a variety of modes, including fantasy, science fiction, horror, mystery, and realistic fiction.

Bradbury was mainly known for his novel Fahrenheit 451 (1953) and his short-story collections The Martian Chronicles (1950) and The Illustrated Man (1951). Most of his best known work is speculative fiction, but he also worked in other genres, such as the coming of age novel Dandelion Wine (1957) and the fictionalized memoir Green Shadows, White Whale (1992). He also wrote and consulted on screenplays and television scripts, including Moby Dick and It Came from Outer Space. Many of his works were adapted into television and film productions as well as comic books.

The New York Times called Bradbury "the writer most responsible for bringing modern science fiction into the literary mainstream."

Early life

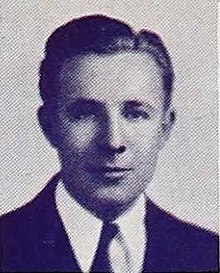

Bradbury was born on August 22, 1920, in Waukegan, Illinois, to Esther (née Moberg) Bradbury (1888–1966), a Swedish immigrant, and Leonard Spaulding Bradbury (1890–1957), a power and telephone lineman of English ancestry. He was given the middle name "Douglas" after the actor Douglas Fairbanks. Bradbury was related to the U.S. Shakespeare scholar Douglas Spaulding and descended from Mary Bradbury, who was tried at one of the Salem witch trials in 1692.

Bradbury was surrounded by an extended family during his early childhood and formative years in Waukegan. An aunt read him short stories when he was a child. This period provided foundations for both the author and his stories. In Bradbury's works of fiction, 1920s Waukegan becomes "Green Town", Illinois.

The Bradbury family lived in Tucson, Arizona, during 1926–1927 and 1932–1933 while their father pursued employment, each time returning to Waukegan. While living in Tucson, Bradbury attended Amphi Junior High School and Roskruge Junior High School. They eventually settled in Los Angeles in 1934 when Bradbury was 14 years old. The family arrived with only US$40 (equivalent to $774 in 2020), which paid for rent and food until his father finally found a job making wire at a cable company for $14 a week (equivalent to $271 in 2020). This meant that they could stay, and Bradbury, who was in love with Hollywood, was ecstatic.

Bradbury attended Los Angeles High School and was active in the drama club. He often roller-skated through Hollywood in hopes of meeting celebrities. Among the creative and talented people Bradbury met were special-effects pioneer Ray Harryhausen and radio star George Burns. Bradbury's first pay as a writer, at age 14, was for a joke he sold to George Burns to use on the Burns and Allen radio show.

Influences

Literature

Throughout his youth, Bradbury was an avid reader and writer and knew at a young age that he was "going into one of the arts." Bradbury began writing his own stories at age 12 (1931) —sometimes writing on butcher paper.

In his youth, he spent much time in the Carnegie Library in Waukegan, reading such authors as H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, and Edgar Allan Poe. At 12, Bradbury began writing traditional horror stories and said he tried to imitate Poe until he was about 18. In addition to comics, he loved the work of Edgar Rice Burroughs, creator of Tarzan of the Apes, especially Burroughs' John Carter of Mars series. The Warlord of Mars impressed him so much that at the age of 12, he wrote his own sequel. The young Bradbury was also a cartoonist and loved to illustrate. He wrote about Tarzan and drew his own Sunday panels. He listened to the radio show Chandu the Magician, and every night when the show went off the air, he would sit and write the entire script from memory.

As a teen in Beverly Hills, he often visited his mentor and friend science-fiction writer Bob Olsen, sharing ideas and maintaining contact. In 1936, at a secondhand bookstore in Hollywood, Bradbury discovered a handbill promoting meetings of the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society. Excited to find that others shared his interest, Bradbury joined a weekly Thursday-night conclave at age 16.

Bradbury cited H. G. Wells and Jules Verne as his primary science-fiction influences. Bradbury identified with Verne, saying, "He believes the human being is in a strange situation in a very strange world, and he believes that we can triumph by behaving morally". Bradbury admitted that he stopped reading science-fiction books in his 20s and embraced a broad field of literature that included poets Alexander Pope and John Donne. Bradbury had just graduated from high school when he met Robert Heinlein, then 31 years old. Bradbury recalled, "He was well known, and he wrote humanistic science fiction, which influenced me to dare to be human instead of mechanical."

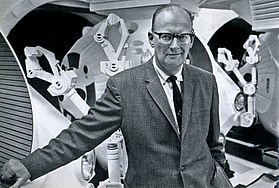

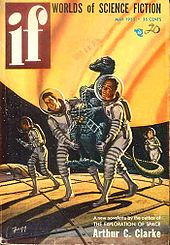

In young adulthood Bradbury read stories published in Astounding Science Fiction, and read everything by Robert A. Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke, and the early writings of Theodore Sturgeon and A. E. van Vogt.

Hollywood

The family lived about four blocks from the Fox Uptown Theatre on Western Avenue in Los Angeles, the flagship theater for MGM and Fox. There, Bradbury learned how to sneak in and watched previews almost every week. He rollerskated there, as well as all over town, as he put it, "hell-bent on getting autographs from glamorous stars. It was glorious." Among stars the young Bradbury was thrilled to encounter were Norma Shearer, Laurel and Hardy, and Ronald Colman. Sometimes, he spent all day in front of Paramount Pictures or Columbia Pictures and then skated to the Brown Derby to watch the stars who came and went for meals. He recounted seeing Cary Grant, Marlene Dietrich, and Mae West, who, he learned, made a regular appearance every Friday night, bodyguard in tow.

Bradbury relates the following meeting (as an adult) with Sergei Bondarchuk, director of Soviet epic film series War and Peace, at a Hollywood award ceremony in Bondarchuk's honor:

They formed a long queue and as Bondarchuk was walking along it he recognized several people: "Oh Mr. Ford, I like your film." He recognized the director, Greta Garbo, and someone else. I was standing at the very end of the queue and silently watched this. Bondarchuk shouted to me; "Ray Bradbury, is that you?" He rushed up to me, embraced me, dragged me inside, grabbed a bottle of Stolichnaya, sat down at his table where his closest friends were sitting. All the famous Hollywood directors in the queue were bewildered. They stared at me and asked each other "Who is this Bradbury?" And, swearing, they left, leaving me alone with Bondarchuk ...

Career

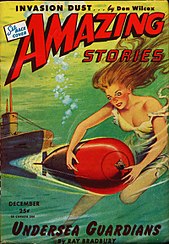

Bradbury's first published story was "Hollerbochen's Dilemma", which appeared in the January 1938 number of Forrest J. Ackerman's fanzine Imagination!. In July 1939, Ackerman and his girlfriend Morojo gave 19-year-old Bradbury the money to head to New York for the First World Science Fiction Convention in New York City, and funded Bradbury's fanzine, titled Futuria Fantasia. Bradbury wrote most of its four issues, each limited to under 100 copies. Between 1940 and 1947, he was a contributor to Rob Wagner's film magazine, Script.

Bradbury was free to start a career in writing when, owing to his bad eyesight, he was rejected for induction into the military during World War II. Having been inspired by science-fiction heroes such as Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, Bradbury began to publish science-fiction stories in fanzines in 1938. Bradbury was invited by Forrest J. Ackerman to attend the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society, which at the time met at Clifton's Cafeteria in downtown Los Angeles. There he met the writers Robert A. Heinlein, Emil Petaja, Fredric Brown, Henry Kuttner, Leigh Brackett and Jack Williamson.

In 1939, Bradbury joined Laraine Day's Wilshire Players Guild, where for two years, he wrote and acted in several plays. They were, as Bradbury later described, "so incredibly bad" that he gave up playwriting for two decades. Bradbury's first paid piece, "Pendulum", written with Henry Hasse, was published in the pulp magazine Super Science Stories in November 1941, for which he earned $15.

Bradbury sold his first solo story, "The Lake", for $13.75 at 22 and became a full-time writer by 24. His first collection of short stories, Dark Carnival, was published in 1947 by Arkham House, a small press in Sauk City, Wisconsin, owned by writer August Derleth. Reviewing Dark Carnival for the New York Herald Tribune, Will Cuppy proclaimed Bradbury "suitable for general consumption" and predicted that he would become a writer of the caliber of British fantasy author John Collier.

After a rejection notice from the pulp Weird Tales, Bradbury submitted "Homecoming" to Mademoiselle, which was spotted by a young editorial assistant named Truman Capote. Capote picked the Bradbury manuscript from a slush pile, which led to its publication. Homecoming won a place in the O. Henry Award Stories of 1947.

In UCLA's Powell Library, in a study room with typewriters for rent, Bradbury wrote his classic story of a book burning future, The Fireman, which was about 25,000 words long. It was later published at about 50,000 words under the name Fahrenheit 451, for a total cost of $9.80, due to the library's typewriter-rental fees of ten cents per half-hour.

A chance encounter in a Los Angeles bookstore with the British expatriate writer Christopher Isherwood gave Bradbury the opportunity to put The Martian Chronicles into the hands of a respected critic. Isherwood's glowing review followed.

Writing

Bradbury attributed his lifelong habit of writing every day to two incidents. The first of these, occurring when he was three years old, was his mother's taking him to see Lon Chaney in the 1923 silent film The Hunchback of Notre Dame. The second incident occurred in 1932, when a carnival entertainer, one Mr. Electrico, touched the young man on the nose with an electrified sword, made his hair stand on end, and shouted, "Live forever!" Bradbury remarked, "I felt that something strange and wonderful had happened to me because of my encounter with Mr. Electrico ... [he] gave me a future ... I began to write, full-time. I have written every single day of my life since that day 69 years ago." At that age, Bradbury first started to do magic, which was his first great love. If he had not discovered writing, he would have become a magician.

Bradbury claimed a wide variety of influences, and described discussions he might have with his favorite poets and writers Robert Frost, William Shakespeare, John Steinbeck, Aldous Huxley, and Thomas Wolfe. From Steinbeck, he said he learned "how to write objectively and yet insert all of the insights without too much extra comment". He studied Eudora Welty for her "remarkable ability to give you atmosphere, character, and motion in a single line". Bradbury's favorite writers growing up included Katherine Anne Porter, Edith Wharton, and Jessamyn West.

Bradbury was once described as a "Midwest surrealist" and is often labeled a science-fiction writer, which he described as "the art of the possible." Bradbury resisted that categorization, however:

First of all, I don't write science fiction. I've only done one science fiction book and that's Fahrenheit 451, based on reality. Science fiction is a depiction of the real. Fantasy is a depiction of the unreal. So Martian Chronicles is not science fiction, it's fantasy. It couldn't happen, you see? That's the reason it's going to be around a long time—because it's a Greek myth, and myths have staying power.

Bradbury recounted when he came into his own as a writer, the afternoon he wrote a short story about his first encounter with death. When he was a boy, he met a young girl at a lake edge and she went out into the water and never came back. Years later, as he wrote about it, tears flowed from him. He recognized he had taken the leap from emulating the many writers he admired to connecting with his voice as a writer.

When later asked about the lyrical power of his prose, Bradbury replied, "From reading so much poetry every day of my life. My favorite writers have been those who've said things well." He is quoted, "If you're reluctant to weep, you won't live a full and complete life."

In high school, Bradbury was active in both the poetry club and the drama club, continuing plans to become an actor, but becoming serious about his writing as his high school years progressed. Bradbury graduated from Los Angeles High School, where he took poetry classes with Snow Longley Housh, and short-story writing courses taught by Jeannet Johnson. The teachers recognized his talent and furthered his interest in writing, but he did not attend college. Instead, he sold newspapers at the corner of South Norton Avenue and Olympic Boulevard. In regard to his education, Bradbury said:

Libraries raised me. I don't believe in colleges and universities. I believe in libraries because most students don't have any money. When I graduated from high school, it was during the Depression and we had no money. I couldn't go to college, so I went to the library three days a week for 10 years.

He told The Paris Review, "You can't learn to write in college. It's a very bad place for writers because the teachers always think they know more than you do – and they don't."

Bradbury described his inspiration as, "My stories run up and bite me in the leg—I respond by writing them down—everything that goes on during the bite. When I finish, the idea lets go and runs off".

"Green Town"

A reinvention of Waukegan, Green Town is a symbol of safety and home, which is often juxtaposed as a contrasting backdrop to tales of fantasy or menace. It serves as the setting of his semiautobiographical classics Dandelion Wine, Something Wicked This Way Comes, and Farewell Summer, as well as in many of his short stories. In Green Town, Bradbury's favorite uncle sprouts wings, traveling carnivals conceal supernatural powers, and his grandparents provide room and board to Charles Dickens. Perhaps the most definitive usage of the pseudonym for his hometown, in Summer Morning, Summer Night, a collection of short stories and vignettes exclusively about Green Town, Bradbury returns to the signature locale as a look back at the rapidly disappearing small-town world of the American heartland, which was the foundation of his roots.

Cultural contributions

Bradbury wrote many short essays on the culture and the arts, attracting the attention of critics in this field, but he used his fiction to explore and criticize his culture and society. Bradbury observed, for example, that Fahrenheit 451 touches on the alienation of people by media:

In writing the short novel Fahrenheit 451 I thought I was describing a world that might evolve in four or five decades. But only a few weeks ago, in Beverly Hills one night, a husband and wife passed me, walking their dog. I stood staring after them, absolutely stunned. The woman held in one hand a small cigarette-package-sized radio, its antenna quivering. From this sprang tiny copper wires which ended in a dainty cone plugged into her right ear. There she was, oblivious to man and dog, listening to far winds and whispers and soap opera cries, sleep walking, helped up and down curbs by a husband who might just as well not have been there. This was not fiction.

Bradbury stated that the novel worked as a critique of the later development of political correctness:

How does the story of Fahrenheit 451 stand up in 1994?

R.B.: It works even better because we have political correctness now. Political correctness is the real enemy these days. The black groups want to control our thinking and you can't say certain things. The homosexual groups don't want you to criticize them. It's thought control and freedom of speech control.

In a 1982 essay, he wrote, "People ask me to predict the Future, when all I want to do is prevent it". This intent had been expressed earlier by other authors, who sometimes attributed it to him.

On May 24, 1956, Bradbury appeared on television in Hollywood on the popular quiz show You Bet Your Life hosted by Groucho Marx. During his introductory comments and on-air banter with Marx, Bradbury briefly discussed some of his books and other works, including giving an overview of "The Veldt", his short story published six years earlier in The Saturday Evening Post under the title "The World the Children Made".

Bradbury was a consultant for the American Pavilion at the 1964 New York World's Fair and wrote the narration script for The American Journey attraction housed there. He also worked on the original exhibit housed in Epcot's Spaceship Earth geosphere at Walt Disney World. Bradbury concentrated on detective fiction in the 1980s. In the latter half of the 1980s and early 1990s, he also hosted The Ray Bradbury Theater, a televised anthology series based on his short stories.

Bradbury was a strong supporter of public library systems, raising money to prevent the closure of several libraries in California facing budgetary cuts. He said "libraries raised me", and shunned colleges and universities, comparing his own lack of funds during the Depression with poor contemporary students. His opinion varied on modern technology. In 1985 Bradbury wrote, "I see nothing but good coming from computers. When they first appeared on the scene, people were saying, 'Oh my God, I'm so afraid.' I hate people like that – I call them the neo-Luddites", and "In a sense, [computers] are simply books. Books are all over the place, and computers will be, too". He resisted the conversion of his work into e-books, saying in 2010, "We have too many cellphones. We've got too many internets. We have got to get rid of those machines. We have too many machines now". When the publishing rights for Fahrenheit 451 came up for renewal in December 2011, Bradbury permitted its publication in electronic form provided that the publisher, Simon & Schuster, allowed the e-book to be digitally downloaded by any library patron. The title remains the only book in the Simon & Schuster catalog where this is possible.

Several comic-book writers have adapted Bradbury's stories. Particularly noted among these were EC Comics' line of horror and science-fiction comics. Initially, the writers plagiarized his stories, but a diplomatic letter from Bradbury about it led to the company paying him and negotiating properly licensed adaptations of his work. The comics featuring Bradbury's stories included Tales from the Crypt, Weird Science, Weird Fantasy, Crime Suspenstories, and Haunt of Fear.

Bradbury remained an enthusiastic playwright all his life, leaving a rich theatrical legacy, as well as literary. Bradbury headed the Pandemonium Theatre Company in Los Angeles for many years and had a five-year relationship with the Fremont Centre Theatre in South Pasadena.

Bradbury is featured prominently in two documentaries related to his classic 1950s–1960s era: Jason V Brock's Charles Beaumont: The Life of Twilight Zone's Magic Man, which details his troubles with Rod Serling, and his friendships with writers Charles Beaumont, George Clayton Johnson, and most especially his dear friend William F. Nolan, as well as Brock's The AckerMonster Chronicles!, which delves into the life of former Bradbury agent, close friend, mega-fan, and Famous Monsters of Filmland editor Forrest J Ackerman.

Bradbury's legacy was celebrated by the bookstore Fahrenheit 451 Books in Laguna Beach, California, in the 1970s and 1980s. Joseph Nicoletti did some Music-Film Consulting for Ray Bradbury for a while, Nicoletti Lived in Laguna Beach and also did work for Wally Heider and Paramount Pictures' The Godfather III. The grand opening of an annex to the store was attended by Bradbury and his favorite illustrator, Joseph Mugnaini, in the mid-1980s. The shop closed its doors in 1987, but in 1990, another shop with the same name (with different owners) opened in Carlsbad, California.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Bradbury served on the advisory board of the Los Angeles Student Film Institute.

Personal life

Bradbury's wife was Marguerite McClure (January 16, 1922 – November 24, 2003) from 1947 until her death; they had four daughters: Susan, Ramona, Bettina and Alexandra. Bradbury never obtained a driver's license, but relied on public transportation or his bicycle. He lived at home until he was 27 and married. His wife of 56 years, Maggie, as she was affectionately called, was the only woman Bradbury ever dated.

He was raised Baptist by his parents, who were themselves infrequent churchgoers. As an adult, Bradbury considered himself a "delicatessen religionist" who resisted categorization of his beliefs and took guidance from both Eastern and Western faiths. He felt that his career was "a God-given thing, and I'm so grateful, so, so grateful. The best description of my career as a writer is 'At play in the fields of the Lord.'"

Bradbury was a close friend of Charles Addams, and Addams illustrated the first of Bradbury's stories about the Elliotts, a family that resembled Addams' own Addams Family placed in rural Illinois. Bradbury's first story about them was "Homecoming", published in the 1946 Halloween issue of Mademoiselle, with Addams' illustrations. Addams and he planned a larger collaborative work that would tell the family's complete history, but it never materialized, and according to a 2001 interview, they went their separate ways. In October 2001, Bradbury published all the Family stories he had written in one book with a connecting narrative, From the Dust Returned, featuring a wraparound Addams cover of the original "Homecoming" illustration.

Another close friend was animator Ray Harryhausen, who was best man at Bradbury's wedding. During a BAFTA 2010 awards tribute in honor of Ray Harryhausen's 90th birthday, Bradbury spoke of his first meeting Harryhausen at Forrest J Ackerman's house when they were both 18 years old. Their shared love for science fiction, King Kong, and the King Vidor-directed film The Fountainhead, written by Ayn Rand, was the beginning of a lifelong friendship. These early influences inspired the pair to believe in themselves and affirm their career choices. After their first meeting, they kept in touch at least once a month, in a friendship that spanned over 70 years.

Late in life, Bradbury retained his dedication and passion despite what he described as the "devastation of illnesses and deaths of many good friends." Among the losses that deeply grieved Bradbury was the death of Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry, who was an intimate friend for many years. They remained close friends for nearly three decades after Roddenberry asked him to write for Star Trek, which Bradbury never did, objecting that he "never had the ability to adapt other people's ideas into any sensible form."

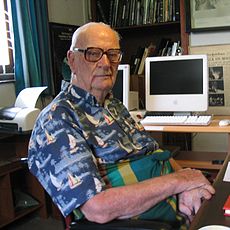

Bradbury suffered a stroke in 1999 that left him partially dependent on a wheelchair for mobility. Despite this, he continued to write, and had even written an essay for The New Yorker, about his inspiration for writing, published only a week prior to his death. Bradbury made regular appearances at science-fiction conventions until 2009, when he retired from the circuit.

Bradbury chose a burial place at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles, with a headstone that reads "Author of Fahrenheit 451". On February 6, 2015, The New York Times reported that the house that Bradbury lived and wrote in for 50 years of his life, at 10265 Cheviot Drive in Cheviot Hills, Los Angeles, California, had been demolished by the buyer, architect Thom Mayne.

Death

Bradbury died in Los Angeles, California, on June 5, 2012, at the age of 91, after a lengthy illness. Bradbury's personal library was willed to the Waukegan Public Library, where he had many of his formative reading experiences.

The New York Times called Bradbury "the writer most responsible for bringing modern science fiction into the literary mainstream." The Los Angeles Times credited Bradbury with the ability "to write lyrically and evocatively of lands an imagination away, worlds he anchored in the here and now with a sense of visual clarity and small-town familiarity". Bradbury's grandson, Danny Karapetian, said Bradbury's works had "influenced so many artists, writers, teachers, scientists, and it's always really touching and comforting to hear their stories". The Washington Post noted several modern day technologies that Bradbury had envisioned much earlier in his writing, such as the idea of banking ATMs and earbuds and Bluetooth headsets from Fahrenheit 451, and the concepts of artificial intelligence within I Sing the Body Electric.

On June 6, 2012, in an official public statement from the White House Press Office, President Barack Obama said:

For many Americans, the news of Ray Bradbury's death immediately brought to mind images from his work, imprinted in our minds, often from a young age. His gift for storytelling reshaped our culture and expanded our world. But Ray also understood that our imaginations could be used as a tool for better understanding, a vehicle for change, and an expression of our most cherished values. There is no doubt that Ray will continue to inspire many more generations with his writing, and our thoughts and prayers are with his family and friends.

Numerous Bradbury fans paid tribute to the author, noting the influence of his works on their own careers and creations. Filmmaker Steven Spielberg stated that Bradbury was "[his] muse for the better part of [his] sci-fi career .... On the world of science fiction and fantasy and imagination he is immortal". Writer Neil Gaiman felt that "the landscape of the world we live in would have been diminished if we had not had him in our world". Author Stephen King released a statement on his website saying, "Ray Bradbury wrote three great novels and three hundred great stories. One of the latter was called 'A Sound of Thunder'. The sound I hear today is the thunder of a giant's footsteps fading away. But the novels and stories remain, in all their resonance and strange beauty."

Bibliography

Bradbury authored "more than 27 novels and story collections", which included many of his 600 short stories. More than eight million copies of his works, published in over 36 languages, have been sold around the world.

First novel

In 1949, Bradbury and his wife were expecting their first child. He took a Greyhound bus to New York and checked into a room at the YMCA for 50 cents a night. He took his short stories to a dozen publishers, but no one wanted them. Just before getting ready to go home, Bradbury had dinner with an editor at Doubleday. When Bradbury recounted that everyone wanted a novel and he did not have one, the editor, coincidentally named Walter Bradbury, asked if the short stories might be tied together into a book-length collection. The title was the editor's idea; he suggested, "You could call it The Martian Chronicles." Bradbury liked the idea and recalled making notes in 1944 to do a book set on Mars. That evening, he stayed up all night at the YMCA and typed out an outline. He took it to the Doubleday editor the next morning, who read it and wrote Bradbury a check for $750. When Bradbury returned to Los Angeles, he connected all the short stories that became The Martian Chronicles.

Intended first novel

What was later issued as a collection of stories and vignettes, Summer Morning, Summer Night, started out to be Bradbury's first true novel. The core of the work was Bradbury's witnessing of the American small-town life in the American heartland.

In the winter of 1955–56, after a consultation with his Doubleday editor, Bradbury deferred publication of a novel based on Green Town, the pseudonym for his hometown. Instead, he extracted 17 stories and, with three other Green Town tales, bridged them into his 1957 book Dandelion Wine. Later, in 2006, Bradbury published the original novel remaining after the extraction, and retitled it Farewell Summer. These two titles show what stories and episodes Bradbury decided to retain as he created the two books out of one.

The most significant of the remaining unpublished stories, scenes, and fragments were published under the originally intended name for the novel, Summer Morning, Summer Night, in 2007.

Adaptations to other media

From 1950 to 1954, 31 of Bradbury's stories were adapted by Al Feldstein for EC Comics (seven of them uncredited in six stories, including "Kaleidoscope" and "Rocket Man" being combined as "Home To Stay"—for which Bradbury was retroactively paid—and EC's first version of "The Handler" under the title "A Strange Undertaking") and 16 of these were collected in the paperbacks, The Autumn People (1965) and Tomorrow Midnight (1966), both published by Ballantine Books with cover illustrations by Frank Frazetta. Also in the early 1950s, adaptations of Bradbury's stories were televised in several anthology shows, including Tales of Tomorrow, Lights Out, Out There, Suspense, CBS Television Workshop, Jane Wyman's Fireside Theatre, Star Tonight, Windows and Alfred Hitchcock Presents. "The Merry-Go-Round", a half-hour film adaptation of Bradbury's "The Black Ferris", praised by Variety, was shown on Starlight Summer Theater in 1954 and NBC's Sneak Preview in 1956. During that same period, several stories were adapted for radio drama, notably on the science fiction anthologies Dimension X and its successor X Minus One.

Producer William Alland first brought Bradbury to movie theaters in 1953 with It Came from Outer Space, a Harry Essex screenplay developed from Bradbury's screen treatment "Atomic Monster". Three weeks later came the release of Eugène Lourié's The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), which featured one scene based on Bradbury's "The Fog Horn", about a sea monster mistaking the sound of a fog horn for the mating cry of a female. Bradbury's close friend Ray Harryhausen produced the stop-motion animation of the creature. Bradbury later returned the favor by writing a short story, "Tyrannosaurus Rex", about a stop-motion animator who strongly resembled Harryhausen. Over the next 50 years, more than 35 features, shorts, and TV movies were based on Bradbury's stories or screenplays. Bradbury was hired in 1953 by director John Huston to work on the screenplay for his film version of Melville's Moby Dick (1956), which stars Gregory Peck as Captain Ahab, Richard Basehart as Ishmael, and Orson Welles as Father Mapple. A significant result of the film was Bradbury's book Green Shadows, White Whale, a semifictionalized account of the making of the film, including Bradbury's dealings with Huston and his time in Ireland, where exterior scenes that were set in New Bedford, Massachusetts, were filmed.

Bradbury's short story I Sing the Body Electric (from the book of the same name) was adapted for the 100th episode of The Twilight Zone. The episode was first aired on May 18, 1962.

Bradbury and director Charles Rome Smith co-founded the Pandemonium Theatre Company in 1964. Its first production was The World of Ray Bradbury, consisting of one-act adaptations of "The Pedestrian", "The Veldt", and "To the Chicago Abyss". It ran for four months at the Coronet Theatre in Los Angeles (October 1964 – February 1965); an off-Broadway production was presented in October 1965. Another Pandemonium Theatre Company production was mounted at the Coronet Theatre in 1965, again presenting adaptations of three Bradbury short stories: "The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit," "The Day It Rained Forever," and "Device Out of Time." (The last was adapted from his 1957 novel Dandelion Wine). The original cast for this production featured Booth Coleman, Joby Baker, Fredric Villani, Arnold Lessing, Eddie Sallia, Keith Taylor, Richard Bull, Gene Otis Shane, Henry T. Delgado, F. Murray Abraham, Anne Loos, and Len Lesser. The director, again, was Charles Rome Smith.

Oskar Werner and Julie Christie starred in Fahrenheit 451 (1966), an adaptation of Bradbury's novel directed by François Truffaut.

In 1966, Bradbury helped Lynn Garrison create AVIAN, a specialist aviation magazine. For the first issue, Bradbury wrote a poem, "Planes That Land on Grass".

In 1969, The Illustrated Man was brought to the big screen, starring Rod Steiger, Claire Bloom, and Robert Drivas. Containing the prologue and three short stories from the book, the film received mediocre reviews. The same year, Bradbury approached composer Jerry Goldsmith, who had worked with Bradbury in dramatic radio of the 1950s and later scored the film version, to compose a cantata Christus Apollo based on Bradbury's text. The work premiered in late 1969, with the California Chamber Symphony performing with narrator Charlton Heston at UCLA.

In 1972, The Screaming Woman was adapted as an ABC Movie-of-the-Week starring Olivia de Havilland.

The Martian Chronicles became a three-part TV miniseries starring Rock Hudson, which was first broadcast by NBC in 1980. Bradbury found the miniseries "just boring".

The 1982 television movie The Electric Grandmother was based on Bradbury's short story "I Sing the Body Electric".

The 1983 horror film Something Wicked This Way Comes, starring Jason Robards and Jonathan Pryce, is based on the Bradbury novel of the same name.

In 1984, Michael McDonough of Brigham Young University produced "Bradbury 13", a series of 13 audio adaptations of famous stories from Bradbury, in conjunction with National Public Radio. The full-cast dramatizations featured adaptations of "The Ravine", "Night Call, Collect", "The Veldt", "There Was an Old Woman", "Kaleidoscope", "Dark They Were, and Golden-Eyed", "The Screaming Woman", "A Sound of Thunder", "The Man", "The Wind", "The Fox and the Forest", "Here There Be Tygers", and "The Happiness Machine". Voiceover actor Paul Frees provided narration, while Bradbury was responsible for the opening voiceover; Greg Hansen and Roger Hoffman scored the episodes. The series won a Peabody Award and two Gold Cindy awards and was released on CD on May 1, 2010. The series began airing on BBC Radio 4 Extra on June 12, 2011.

From 1985 to 1992, Bradbury hosted a syndicated anthology television series, The Ray Bradbury Theater, for which he adapted 65 of his stories. Each episode began with a shot of Bradbury in his office, gazing over mementoes of his life, which he states (in narrative) are used to spark ideas for stories. During the first two seasons, Bradbury also provided additional voiceover narration specific to the featured story and appeared on screen.

Deeply respected in the USSR, Bradbury's fiction has been adapted into five episodes of the Soviet science-fiction TV series This Fantastic World which adapted the stories film version of "I Sing The Body Electric", Fahrenheit 451, "A Piece of Wood", "To the Chicago Abyss", and "Forever and the Earth". In 1984 a cartoon adaptation of There Will Come Soft Rains («Будет ласковый дождь») came out by Uzbek director Nazim Tyuhladziev. He made a film adaptation of The Veldt in 1987. In 1989, a cartoon adaptation of "Here There Be Tygers" («Здесь могут водиться тигры») by director Vladimir Samsonov came out.

Bradbury wrote and narrated the 1993 animated television version of The Halloween Tree, based on his 1972 novel.

The 1998 film The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit, released by Touchstone Pictures, was written by Bradbury. It was based on his story "The Magic White Suit" originally published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1957. The story had also previously been adapted as a play, a musical, and a 1958 television version.

In 2002, Bradbury's own Pandemonium Theatre Company production of Fahrenheit 451 at Burbank's Falcon Theatre combined live acting with projected digital animation by the Pixel Pups. In 1984, Telarium released a game for Commodore 64 based on Fahrenheit 451.

In 2005, the film A Sound of Thunder was released, loosely based upon the short story of the same name. The film The Butterfly Effect revolves around the same theory as A Sound of Thunder and contains many references to its inspiration. Short film adaptations of A Piece of Wood and The Small Assassin were released in 2005 and 2007, respectively.

In 2005, it was reported that Bradbury was upset with filmmaker Michael Moore for using the title Fahrenheit 9/11, which is an allusion to Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, for his documentary about the George W. Bush administration. Bradbury expressed displeasure with Moore's use of the title, but stated that his resentment was not politically motivated, though Bradbury was conservative-leaning politically. Bradbury asserted that he did not want any of the money made by the movie, nor did he believe that he deserved it. He pressured Moore to change the name, but to no avail. Moore called Bradbury two weeks before the film's release to apologize, saying that the film's marketing had been set in motion a long time ago and it was too late to change the title.

In 2008, the film Ray Bradbury's Chrysalis was produced by Roger Lay Jr. for Urban Archipelago Films, based upon the short story of the same name. The film won the best feature award at the International Horror and Sci-Fi Film Festival in Phoenix. The film has international distribution by Arsenal Pictures and domestic distribution by Lightning Entertainment.

In 2010, The Martian Chronicles was adapted for radio by Colonial Radio Theatre on the Air.

Bradbury's works and approach to writing are documented in Terry Sanders' film Ray Bradbury: Story of a Writer (1963).

Bradbury's poem "Groon" was voiced as a tribute in 2012.

Awards and honors

The Ray Bradbury Award for excellency in screenwriting was occasionally presented by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America – presented to six people on four occasions from 1992 to 2009. Beginning 2010, the Ray Bradbury Award for Outstanding Dramatic Presentation is presented annually according to Nebula Awards rules and procedures, although it is not a Nebula Award. The revamped Bradbury Award replaced the Nebula Award for Best Script.

- In 1971, an impact crater on the Moon was named Dandelion Crater by the Apollo 15 astronauts, in honour of Bradbury's novel Dandelion Wine.

- In 1979, he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Letters (Litt.D.) degree from Whittier College.

- In 1984, he received the Prometheus Award for Fahrenheit 451.

- In 1986, Ray Bradbury was a Guest of Honor at the 44th World Science Fiction Convention, which was held in Atlanta, Ga., from August 28 to September 1.

- Ray Bradbury Park was dedicated in Waukegan, Illinois, in 1990. He was present for the ribbon-cutting ceremony. The park contains locations described in Dandelion Wine, most notably the "113 steps". In 2009, a panel designed by artist Michael Pavelich was added to the park detailing the history of Ray Bradbury and Ray Bradbury Park.

- An asteroid discovered in 1992 was named "9766 Bradbury" in his honor.

- In 1994, he received the Peggy V. Helmerich Distinguished Author Award, presented annually by the Tulsa Library Trust.

- In 1994, he won an Emmy Award for the screenplay The Halloween Tree.

- In 2000, he was awarded the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters from the National Book Foundation.

- For his contribution to the motion picture industry, Bradbury was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on April 1, 2002.

- In 2003, he received an honorary doctorate from Woodbury University, where he presented the Ray Bradbury Creativity Award each year until his death.

- On November 17, 2004, Bradbury received the National Medal of Arts, presented by President George W. Bush and Laura Bush.

- Bradbury received a World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement at the 1977 World Fantasy Convention and was named Gandalf Grand Master of Fantasy at the 1980 World Science Fiction Convention. In 1989 the Horror Writers Association gave him the fourth or fifth Bram Stoker Award for Lifetime Achievement in horror fiction and the Science Fiction Writers of America made him its 10th SFWA Grand Master. He won a First Fandom Hall of Fame Award in 1996 and the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame inducted him in 1999, its fourth class of two deceased and two living writers.

- In 2005, he was awarded the degree of Doctor of Laws (honoris causa) by the National University of Ireland, Galway, at a conferring ceremony in Los Angeles.

- On April 14, 2007, Bradbury received the Sir Arthur Clarke Award's Special Award, given by Clarke to a recipient of his choice.

- On April 16, 2007, Bradbury received a special citation by the Pulitzer Prize jury "for his distinguished, prolific, and deeply influential career as an unmatched author of science fiction and fantasy."

- In 2007, Bradbury was made a Commandeur (Commander) of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (Order of the Arts and Letters) by the French government.

- In 2008, he was named SFPA Grandmaster.

- On May 17, 2008, Bradbury received the inaugural J. Lloyd Eaton Lifetime Achievement Award in Science Fiction, presented by the UCR Libraries at the 2008 Eaton Science Fiction Conference, "Chronicling Mars".

- On November 19, 2008, Bradbury was presented with the Illinois Literary Heritage Award by the Illinois Center for the Book.

- In 2009, Bradbury was awarded an Honorary Doctorate by Columbia College Chicago.

- In 2010, Spike TV Scream Awards Comic-Con Icon Award went to Bradbury

- In 2012, the NASA Curiosity rover landing site (4.5895°S 137.4417°E) on the planet Mars was named "Bradbury Landing".

- On December 6, 2012, the Los Angeles street corner at 5th and Flower Streets was named "Ray Bradbury Square" in his honor.

- On February 24, 2013, Bradbury was honored at the 85th Academy Awards during that event's "In Memoriam" segment.