Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from the effects of antimicrobials. Antibiotic resistance is a subset of AMR, that applies specifically to bacteria that become resistant to antibiotics. Infections caused by resistant microbes are more difficult to treat, requiring higher doses of antimicrobial drugs, or alternative medications which may prove more toxic. These approaches may also be more expensive. Microbes resistant to multiple antimicrobials are called multidrug resistant (MDR).

All classes of microbes can evolve resistance. Fungi evolve antifungal resistance. Viruses evolve antiviral resistance. Protozoa evolve antiprotozoal resistance, and bacteria evolve antibiotic resistance. Those bacteria that are considered extensively drug resistant (XDR) or totally drug-resistant (TDR) are sometimes called "superbugs". Resistance in bacteria can arise naturally by genetic mutation, or by one species acquiring resistance from another. Resistance can appear spontaneously because of random mutations. However, extended use of antimicrobials appears to encourage selection for mutations which can render antimicrobials ineffective.

The prevention of antibiotic misuse, which can lead to antibiotic resistance, includes taking antibiotics only when prescribed. Narrow-spectrum antibiotics are preferred over broad-spectrum antibiotics when possible, as effectively and accurately targeting specific organisms is less likely to cause resistance, as well as side effects. For people who take these medications at home, education about proper use is essential. Health care providers can minimize spread of resistant infections by use of proper sanitation and hygiene, including handwashing and disinfecting between patients, and should encourage the same of the patient, visitors, and family members.

Rising drug resistance is caused mainly by use of antimicrobials in humans and other animals, and spread of resistant strains between the two. Growing resistance has also been linked to releasing inadequately treated effluents from the pharmaceutical industry, especially in countries where bulk drugs are manufactured. Antibiotics increase selective pressure in bacterial populations, causing vulnerable bacteria to die; this increases the percentage of resistant bacteria which continue growing. Even at very low levels of antibiotic, resistant bacteria can have a growth advantage and grow faster than vulnerable bacteria. As resistance to antibiotics becomes more common there is greater need for alternative treatments. Calls for new antibiotic therapies have been issued, but new drug development is becoming rarer.

Antimicrobial resistance is increasing globally due to increased prescription and dispensing of antibiotic drugs in developing countries. Estimates are that 700,000 to several million deaths result per year and continues to pose a major public health threat worldwide. Each year in the United States, at least 2.8 million people become infected with bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics and at least 35,000 people die and US$55 billion in increased health care costs and lost productivity. According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, three hundred and fifty million deaths could be caused by AMR by 2050. By then, the yearly death toll will be ten million, according to a United Nations report.

There are public calls for global collective action to address the threat that include proposals for international treaties on antimicrobial resistance. Worldwide antibiotic resistance is not completely identified, but poorer countries with weaker healthcare systems are more affected. During the COVID-19 pandemic, action against antimicrobial resistance slowed due to scientists focusing more on SARS-CoV-2 research.

Definition

The WHO defines antimicrobial resistance as a microorganism's resistance to an antimicrobial drug that was once able to treat an infection by that microorganism. A person cannot become resistant to antibiotics. Resistance is a property of the microbe, not a person or other organism infected by a microbe.

Antibiotic resistance is a subset of antimicrobial resistance. This more specified resistance is linked to pathogenic bacteria and thus broken down into two further subsets, microbiological and clinical. Resistance linked microbiologically is the most common and occurs from genes, mutated or inherited, that allow the bacteria to resist the mechanism associated with certain antibiotics. Clinical resistance is shown through the failure of many therapeutic techniques where the bacteria that are normally susceptible to a treatment become resistant after surviving the outcome of the treatment. In both cases of acquired resistance, the bacteria can pass the genetic catalyst for resistance through conjugation, transduction, or transformation. This allows the resistance to spread across the same pathogen or even similar bacterial pathogens.

Overview

WHO report released April 2014 stated, "this serious threat is no longer a prediction for the future, it is happening right now in every region of the world and has the potential to affect anyone, of any age, in any country. Antibiotic resistance—when bacteria change so antibiotics no longer work in people who need them to treat infections—is now a major threat to public health." In 2018, WHO considered antibiotic resistance to be one of the biggest threats to global health, food security and development. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control calculated that in 2015 there were 671,689 infections in the EU and European Economic Area caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria, resulting in 33,110 deaths. Most were acquired in healthcare settings.

Causes

Antimicrobial resistance is mainly caused by the overuse of antimicrobials. This leads to microbes either evolving a defense against drugs used to treat them, or certain strains of microbes that have a natural resistance to antimicrobials becoming much more prevalent than the ones that are easily defeated with medication. While antimicrobial resistance does occur naturally over time, the use of antimicrobial agents in a variety of settings both within the healthcare industry and outside of has led to antimicrobial resistance becoming increasingly more prevalent.

Natural occurrence

Antimicrobial resistance can evolve naturally due to continued exposure to antimicrobials. Natural selection means that organisms that are able to adapt to their environment, survive, and continue to produce offspring. As a result, the types of microorganisms that are able to survive over time with continued attack by certain antimicrobial agents will naturally become more prevalent in the environment, and those without this resistance will become obsolete. Over time most of the strains of bacteria and infections present will be the type resistant to the antimicrobial agent being used to treat them, making this agent now ineffective to defeat most microbes. With the increased use of antimicrobial agents, there is a speeding up of this natural process.

Self-medication

Self-medication by consumers is defined as "the taking of medicines on one's own initiative or on another person's suggestion, who is not a certified medical professional", and it has been identified as one of the primary reasons for the evolution of antimicrobial resistance. In an effort to manage their own illness, patients take the advice of false media sources, friends, and family causing them to take antimicrobials unnecessarily or in excess. Many people resort to this out of necessity, when they have a limited amount of money to see a doctor, or in many developing countries a poorly developed economy and lack of doctors are the cause of self-medication. In these developing countries, governments resort to allowing the sale of antimicrobials as over the counter medications so people could have access to them without having to find or pay to see a medical professional. This increased access makes it extremely easy to obtain antimicrobials without the advice of a physician, and as a result many antimicrobials are taken incorrectly leading to resistant microbial strains. One major example of a place that faces these challenges is India, where in the state of Punjab 73% of the population resorted to treating their minor health issues and chronic illnesses through self-medication.

The major issue with self-medication is the lack of knowledge of the public on the dangerous effects of antimicrobial resistance, and how they can contribute to it through mistreating or misdiagnosing themselves. In order to determine the public's knowledge and preconceived notions on antibiotic resistance, a major type of antimicrobial resistance, a screening of 3537 articles published in Europe, Asia, and North America was done. Of the 55,225 total people surveyed, 70% had heard of antibiotic resistance previously, but 88% of those people thought it referred to some type of physical change in the body. With so many people around the world with the ability to self-medicate using antibiotics, and a vast majority unaware of what antimicrobial resistance is, it makes the increase of antimicrobial resistance much more likely.

Clinical misuse

Clinical misuse by healthcare professionals is another cause leading to increased antimicrobial resistance. Studies done by the CDC show that the indication for treatment of antibiotics, choice of the agent used, and the duration of therapy was incorrect in up to 50% of the cases studied. In another study done in an intensive care unit in a major hospital in France, it was shown that 30% to 60% of prescribed antibiotics were unnecessary. These inappropriate uses of antimicrobial agents promote the evolution of antimicrobial resistance by supporting the bacteria in developing genetic alterations that lead to resistance. In a study done by the American Journal of Infection Control aimed to evaluate physicians’ attitudes and knowledge on antimicrobial resistance in ambulatory settings, only 63% of those surveyed reported antibiotic resistance as a problem in their local practices, while 23% reported the aggressive prescription of antibiotics as necessary to avoid failing to provide adequate care. This demonstrates how a majority of doctors underestimate the impact that their own prescribing habits have on antimicrobial resistance as a whole. It also confirms that some physicians may be overly cautious when it comes to prescribing antibiotics for both medical or legal reasons, even when indication for use for these medications is not always confirmed. This can lead to unnecessary antimicrobial use.

Studies have shown that common misconceptions about the effectiveness and necessity of antibiotics to treat common mild illnesses contribute to their overuse.

Environmental pollution

Untreated effluents from pharmaceutical manufacturing industries, hospitals and clinics, and inappropriate disposal of unused or expired medication can expose microbes in the environment to antibiotics and trigger the evolution of resistance.

Food production

Livestock

The antimicrobial resistance crisis also extends to the food industry, specifically with food producing animals. Antibiotics are fed to livestock to act as growth supplements, and a preventative measure to decrease the likelihood of infections. This results in the transfer of resistant bacterial strains into the food that humans eat, causing potentially fatal transfer of disease. While this practice does result in better yields and meat products, it is a major issue in terms of preventing antimicrobial resistance. Though the evidence linking antimicrobial usage in livestock to antimicrobial resistance is limited, the World Health Organization Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance strongly recommended the reduction of use of medically important antimicrobials in livestock. Additionally, the Advisory Group stated that such antimicrobials should be expressly prohibited for both growth promotion and disease prevention.

In a study published by the National Academy of Sciences mapping antimicrobial consumption in livestock globally, it was predicted that in the 228 countries studied, there would be a total 67% increase in consumption of antibiotics by livestock by 2030. In some countries such as Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa it is predicted that a 99% increase will occur. Several countries have restricted the use of antibiotics in livestock, including Canada, China, Japan, and the US. These restrictions are sometimes associated with a reduction of the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in humans.

Pesticides

Most pesticides protect crops against insects and plants, but in some cases antimicrobial pesticides are used to protect against various microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, algae, and protozoa. The overuse of many pesticides in an effort to have a higher yield of crops has resulted in many of these microbes evolving a tolerance against these antimicrobial agents. Currently there are over 4000 antimicrobial pesticides registered with the EPA and sold to market, showing the widespread use of these agents. It is estimated that for every single meal a person consumes, 0.3 g of pesticides is used, as 90% of all pesticide use is used on agriculture. A majority of these products are used to help defend against the spread of infectious diseases, and hopefully protect public health. But out of the large amount of pesticides used, it is also estimated that less than 0.1% of those antimicrobial agents, actually reach their targets. That leaves over 99% of all pesticides used available to contaminate other resources. In soil, air, and water these antimicrobial agents are able to spread, coming in contact with more microorganisms and leading to these microbes evolving mechanisms to tolerate and further resist pesticides.

Prevention

There have been increasing public calls for global collective action to address the threat, including a proposal for international treaty on antimicrobial resistance. Further detail and attention is still needed in order to recognize and measure trends in resistance on the international level; the idea of a global tracking system has been suggested but implementation has yet to occur. A system of this nature would provide insight to areas of high resistance as well as information necessary for evaluating programs and other changes made to fight or reverse antibiotic resistance.

Duration of antibiotics

Antibiotic treatment duration should be based on the infection and other health problems a person may have. For many infections once a person has improved there is little evidence that stopping treatment causes more resistance. Some therefore feel that stopping early may be reasonable in some cases. Other infections, however, do require long courses regardless of whether a person feels better.

Monitoring and mapping

There are multiple national and international monitoring programs for drug-resistant threats, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA), extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), and multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (MRAB).

ResistanceOpen is an online global map of antimicrobial resistance developed by HealthMap which displays aggregated data on antimicrobial resistance from publicly available and user submitted data. The website can display data for a 25-mile radius from a location. Users may submit data from antibiograms for individual hospitals or laboratories. European data is from the EARS-Net (European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network), part of the ECDC.

ResistanceMap is a website by the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy and provides data on antimicrobial resistance on a global level.

Limiting antibiotic use

Antibiotic stewardship programmes appear useful in reducing rates of antibiotic resistance. The antibiotic stewardship program will also provide pharmacists with the knowledge to educate patients that antibiotics will not work for a virus.

Excessive antibiotic use has become one of the top contributors to the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Since the beginning of the antibiotic era, antibiotics have been used to treat a wide range of disease. Overuse of antibiotics has become the primary cause of rising levels of antibiotic resistance. The main problem is that doctors are willing to prescribe antibiotics to ill-informed individuals who believe that antibiotics can cure nearly all illnesses, including viral infections like the common cold. In an analysis of drug prescriptions, 36% of individuals with a cold or an upper respiratory infection (both viral in origin) were given prescriptions for antibiotics. These prescriptions accomplished nothing other than increasing the risk of further evolution of antibiotic resistant bacteria. Using antibiotics without prescription is another driving force leading to the overuse of antibiotics to self-treat diseases like the common cold, cough, fever, and dysentery resulting in a pandemic of antibiotic resistance in countries like Bangladesh, risking its spread around the globe. Introducing strict antibiotic stewardship in the outpatient setting may reduce the emerging bacterial resistance.

At the hospital level

Antimicrobial stewardship teams in hospitals are encouraging optimal use of antimicrobials. The goals of antimicrobial stewardship are to help practitioners pick the right drug at the right dose and duration of therapy while preventing misuse and minimizing the development of resistance. Stewardship may reduce the length of stay by an average of slightly over 1 day while not increasing the risk of death.

At the farming level

It is established that the use of antibiotics in animal husbandry can give rise to AMR resistances in bacteria found in food animals to the antibiotics being administered (through injections or medicated feeds). For this reason only antimicrobials that are deemed "not-clinically relevant" are used in these practices.

Recent studies have shown that the prophylactic use of "non-priority" or "non-clinically relevant" antimicrobials in feeds can potentially, under certain conditions, lead to co-selection of environmental AMR bacteria with resistance to medically important antibiotics. The possibility for co-selection of AMR resistances in the food chain pipeline may have far-reaching implications for human health.

At the level of GP

Given the volume of care provided in primary care (General Practice), recent strategies have focused on reducing unnecessary antibiotic prescribing in this setting. Simple interventions, such as written information explaining the futility of antibiotics for common infections such as upper respiratory tract infections, have been shown to reduce antibiotic prescribing.

The prescriber should closely adhere to the five rights of drug administration: the right patient, the right drug, the right dose, the right route, and the right time.

Cultures should be taken before treatment when indicated and treatment potentially changed based on the susceptibility report.

About a third of antibiotic prescriptions written in outpatient settings in the United States were not appropriate in 2010 and 2011. Doctors in the U.S. wrote 506 annual antibiotic scripts for every 1,000 people, with 353 being medically necessary.

Health workers and pharmacists can help tackle resistance by: enhancing infection prevention and control; only prescribing and dispensing antibiotics when they are truly needed; prescribing and dispensing the right antibiotic(s) to treat the illness.

At the individual level

People can help tackle resistance by using antibiotics only when prescribed by a doctor; completing the full prescription, even if they feel better; never sharing antibiotics with others or using leftover prescriptions.

Country examples

- The Netherlands has the lowest rate of antibiotic prescribing in the OECD, at a rate of 11.4 defined daily doses (DDD) per 1,000 people per day in 2011.

- Germany and Sweden also have lower prescribing rates, with Sweden's rate having been declining since 2007.

- Greece, France and Belgium have high prescribing rates of more than 28 DDD.

Water, sanitation, hygiene

Infectious disease control through improved water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure needs to be included in the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) agenda. The "Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance" stated in 2018 that "the spread of pathogens through unsafe water results in a high burden of gastrointestinal disease, increasing even further the need for antibiotic treatment." This is particularly a problem in developing countries where the spread of infectious diseases caused by inadequate WASH standards is a major driver of antibiotic demand. Growing usage of antibiotics together with persistent infectious disease levels have led to a dangerous cycle in which reliance on antimicrobials increases while the efficacy of drugs diminishes. The proper use of infrastructure for water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) can result in a 47–72 percent decrease of diarrhea cases treated with antibiotics depending on the type of intervention and its effectiveness. A reduction of the diarrhea disease burden through improved infrastructure would result in large decreases in the number of diarrhea cases treated with antibiotics. This was estimated as ranging from 5 million in Brazil to up to 590 million in India by the year 2030. The strong link between increased consumption and resistance indicates that this will directly mitigate the accelerating spread of AMR. Sanitation and water for all by 2030 is Goal Number 6 of the Sustainable Development Goals.

An increase in hand washing compliance by hospital staff results in decreased rates of resistant organisms.

Water supply and sanitation infrastructure in health facilities offer significant co-benefits for combatting AMR, and investment should be increased. There is much room for improvement: WHO and UNICEF estimated in 2015 that globally 38% of health facilities did not have a source of water, nearly 19% had no toilets and 35% had no water and soap or alcohol-based hand rub for handwashing.

Industrial wastewater treatment

Manufacturers of antimicrobials need to improve the treatment of their wastewater (by using industrial wastewater treatment processes) to reduce the release of residues into the environment.

Management in animal use

Europe

In 1997, European Union health ministers voted to ban avoparcin and four additional antibiotics used to promote animal growth in 1999. In 2006 a ban on the use of antibiotics in European feed, with the exception of two antibiotics in poultry feeds, became effective. In Scandinavia, there is evidence that the ban has led to a lower prevalence of antibiotic resistance in (nonhazardous) animal bacterial populations. As of 2004, several European countries established a decline of antimicrobial resistance in humans through limiting the use of antimicrobials in agriculture and food industries without jeopardizing animal health or economic cost.

United States

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) collect data on antibiotic use in humans and in a more limited fashion in animals. The FDA first determined in 1977 that there is evidence of emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains in livestock. The long-established practice of permitting OTC sales of antibiotics (including penicillin and other drugs) to lay animal owners for administration to their own animals nonetheless continued in all states. In 2000, the FDA announced their intention to revoke approval of fluoroquinolone use in poultry production because of substantial evidence linking it to the emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter infections in humans. Legal challenges from the food animal and pharmaceutical industries delayed the final decision to do so until 2006. Fluroquinolones have been banned from extra-label use in food animals in the USA since 2007. However, they remain widely used in companion and exotic animals.

Global action plans and awareness

The increasing interconnectedness of the world and the fact that new classes of antibiotics have not been developed and approved for more than 25 years highlight the extent to which antimicrobial resistance is a global health challenge. A global action plan to tackle the growing problem of resistance to antibiotics and other antimicrobial medicines was endorsed at the Sixty-eighth World Health Assembly in May 2015. One of the key objectives of the plan is to improve awareness and understanding of antimicrobial resistance through effective communication, education and training. This global action plan developed by the World Health Organization was created to combat the issue of antimicrobial resistance and was guided by the advice of countries and key stakeholders. The WHO's global action plan is composed of five key objectives that can be targeted through different means, and represents countries coming together to solve a major problem that can have future health consequences. These objectives are as follows:

- improve awareness and understanding of antimicrobial resistance through effective communication, education and training.

- strengthen the knowledge and evidence base through surveillance and research.

- reduce the incidence of infection through effective sanitation, hygiene and infection prevention measures.

- optimize the use of antimicrobial medicines in human and animal health.

- develop the economic case for sustainable investment that takes account of the needs of all countries and to increase investment in new medicines, diagnostic tools, vaccines and other interventions.

Steps towards progress

- React based in Sweden has produced informative material on AMR for the general public.

- Videos are being produced for the general public to generate interest and awareness.

- The Irish Department of Health published a National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance in October 2017. The Strategy for the Control of Antimicrobial Resistance in Ireland (SARI), Iaunched in 2001 developed Guidelines for Antimicrobial Stewardship in Hospitals in Ireland in conjunction with the Health Protection Surveillance Centre, these were published in 2009. Following their publication a public information campaign 'Action on Antibiotics' was launched to highlight the need for a change in antibiotic prescribing. Despite this, antibiotic prescribing remains high with variance in adherence to guidelines.

Antibiotic Awareness Week

The World Health Organization has promoted the first World Antibiotic Awareness Week running from 16 to 22 November 2015. The aim of the week is to increase global awareness of antibiotic resistance. It also wants to promote the correct usage of antibiotics across all fields in order to prevent further instances of antibiotic resistance.

World Antibiotic Awareness Week has been held every November since 2015. For 2017, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) are together calling for responsible use of antibiotics in humans and animals to reduce the emergence of antibiotic resistance.

United Nations

In 2016 the Secretary-General of the United Nations convened the Interagency Coordination Group (IACG) on Antimicrobial Resistance. The IACG worked with international organizations and experts in human, animal, and plant health to create a plan to fight antimicrobial resistance. Their report released in April 2019 highlights the seriousness of antimicrobial resistance and the threat it poses to world health. It suggests five recommendations for member states to follow in order to tackle this increasing threat. The IACG recommendations are as follows:

- Accelerate progress in countries

- Innovate to secure the future

- Collaborate for more effective action

- Invest for a sustainable response

- Strengthen accountability and global governance

Mechanisms and organisms

Bacteria

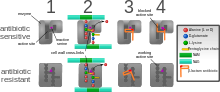

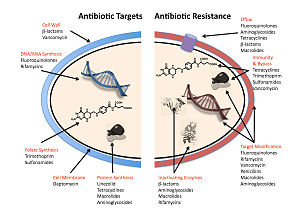

The five main mechanisms by which bacteria exhibit resistance to antibiotics are:

- Drug inactivation or modification: for example, enzymatic deactivation of penicillin G in some penicillin-resistant bacteria through the production of β-lactamases. Drugs may also be chemically modified through the addition of functional groups by transferase enzymes; for example, acetylation, phosphorylation, or adenylation are common resistance mechanisms to aminoglycosides. Acetylation is the most widely used mechanism and can affect a number of drug classes.

- Alteration of target- or binding site: for example, alteration of PBP—the binding target site of penicillins—in MRSA and other penicillin-resistant bacteria. Another protective mechanism found among bacterial species is ribosomal protection proteins. These proteins protect the bacterial cell from antibiotics that target the cell's ribosomes to inhibit protein synthesis. The mechanism involves the binding of the ribosomal protection proteins to the ribosomes of the bacterial cell, which in turn changes its conformational shape. This allows the ribosomes to continue synthesizing proteins essential to the cell while preventing antibiotics from binding to the ribosome to inhibit protein synthesis.

- Alteration of metabolic pathway: for example, some sulfonamide-resistant bacteria do not require para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA), an important precursor for the synthesis of folic acid and nucleic acids in bacteria inhibited by sulfonamides, instead, like mammalian cells, they turn to using preformed folic acid.

- Reduced drug accumulation: by decreasing drug permeability or increasing active efflux (pumping out) of the drugs across the cell surface These pumps within the cellular membrane of certain bacterial species are used to pump antibiotics out of the cell before they are able to do any damage. They are often activated by a specific substrate associated with an antibiotic, as in fluoroquinolone resistance.

- Ribosome splitting and recycling: for example, drug-mediated stalling of the ribosome by lincomycin and erythromycin unstalled by a heat shock protein found in Listeria monocytogenes, which is a homologue of HflX from other bacteria. Liberation of the ribosome from the drug allows further translation and consequent resistance to the drug.

There are several different types of germs that have developed a resistance over time. For example, Penicillinase-producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae developed a resistance to penicillin in 1976. Another example is Azithromycin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae, which developed a resistance to azithromycin in 2011.

In gram-negative bacteria, plasmid-mediated resistance genes produce proteins that can bind to DNA gyrase, protecting it from the action of quinolones. Finally, mutations at key sites in DNA gyrase or topoisomerase IV can decrease their binding affinity to quinolones, decreasing the drug's effectiveness.

Some bacteria are naturally resistant to certain antibiotics; for example, gram-negative bacteria are resistant to most β-lactam antibiotics due to the presence of β-lactamase. Antibiotic resistance can also be acquired as a result of either genetic mutation or horizontal gene transfer. Although mutations are rare, with spontaneous mutations in the pathogen genome occurring at a rate of about 1 in 105 to 1 in 108 per chromosomal replication, the fact that bacteria reproduce at a high rate allows for the effect to be significant. Given that lifespans and production of new generations can be on a timescale of mere hours, a new (de novo) mutation in a parent cell can quickly become an inherited mutation of widespread prevalence, resulting in the microevolution of a fully resistant colony. However, chromosomal mutations also confer a cost of fitness. For example, a ribosomal mutation may protect a bacterial cell by changing the binding site of an antibiotic but may result in slower growth rate. Moreover, some adaptive mutations can propagate not only through inheritance but also through horizontal gene transfer. The most common mechanism of horizontal gene transfer is the transferring of plasmids carrying antibiotic resistance genes between bacteria of the same or different species via conjugation. However, bacteria can also acquire resistance through transformation, as in Streptococcus pneumoniae uptaking of naked fragments of extracellular DNA that contain antibiotic resistance genes to streptomycin, through transduction, as in the bacteriophage-mediated transfer of tetracycline resistance genes between strains of S. pyogenes, or through gene transfer agents, which are particles produced by the host cell that resemble bacteriophage structures and are capable of transferring DNA.

Antibiotic resistance can be introduced artificially into a microorganism through laboratory protocols, sometimes used as a selectable marker to examine the mechanisms of gene transfer or to identify individuals that absorbed a piece of DNA that included the resistance gene and another gene of interest.

Recent findings show no necessity of large populations of bacteria for the appearance of antibiotic resistance. Small populations of Escherichia coli in an antibiotic gradient can become resistant. Any heterogeneous environment with respect to nutrient and antibiotic gradients may facilitate antibiotic resistance in small bacterial populations. Researchers hypothesize that the mechanism of resistance evolution is based on four SNP mutations in the genome of E. coli produced by the gradient of antibiotic.

In one study, which has implications for space microbiology, a non-pathogenic strain E. coli MG1655 was exposed to trace levels of the broad spectrum antibiotic chloramphenicol, under simulated microgravity (LSMMG, or, Low Shear Modeled Microgravity) over 1000 generations. The adapted strain acquired resistance to not only chloramphenicol, but also cross-resistance to other antibiotics; this was in contrast to the observation on the same strain, which was adapted to over 1000 generations under LSMMG, but without any antibiotic exposure; the strain in this case did not acquire any such resistance. Thus, irrespective of where they are used, the use of an antibiotic would likely result in persistent resistance to that antibiotic, as well as cross-resistance to other antimicrobials.

In recent years, the emergence and spread of β-lactamases called carbapenemases has become a major health crisis. One such carbapenemase is New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1 (NDM-1), an enzyme that makes bacteria resistant to a broad range of beta-lactam antibiotics. The most common bacteria that make this enzyme are gram-negative such as E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, but the gene for NDM-1 can spread from one strain of bacteria to another by horizontal gene transfer.

Viruses

Specific antiviral drugs are used to treat some viral infections. These drugs prevent viruses from reproducing by inhibiting essential stages of the virus's replication cycle in infected cells. Antivirals are used to treat HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, influenza, herpes viruses including varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus. With each virus, some strains have become resistant to the administered drugs.

Antiviral drugs typically target key components of viral reproduction; for example, oseltamivir targets influenza neuraminidase, while guanosine analogs inhibit viral DNA polymerase. Resistance to antivirals is thus acquired through mutations in the genes that encode the protein targets of the drugs.

Resistance to HIV antivirals is problematic, and even multi-drug resistant strains have evolved. One source of resistance is that many current HIV drugs, including NRTIs and NNRTIs, target reverse transcriptase; however, HIV-1 reverse transcriptase is highly error prone and thus mutations conferring resistance arise rapidly. Resistant strains of the HIV virus emerge rapidly if only one antiviral drug is used. Using three or more drugs together, termed combination therapy, has helped to control this problem, but new drugs are needed because of the continuing emergence of drug-resistant HIV strains.

Fungi

Infections by fungi are a cause of high morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised persons, such as those with HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis or receiving chemotherapy. The fungi candida, Cryptococcus neoformans and Aspergillus fumigatus cause most of these infections and antifungal resistance occurs in all of them. Multidrug resistance in fungi is increasing because of the widespread use of antifungal drugs to treat infections in immunocompromised individuals.

Of particular note, Fluconazole-resistant Candida species have been highlighted as a growing problem by the CDC. More than 20 species of Candida can cause Candidiasis infection, the most common of which is Candida albicans. Candida yeasts normally inhabit the skin and mucous membranes without causing infection. However, overgrowth of Candida can lead to Candidiasis. Some Candida strains are becoming resistant to first-line and second-line antifungal agents such as azoles and echinocandins.

Parasites

The protozoan parasites that cause the diseases malaria, trypanosomiasis, toxoplasmosis, cryptosporidiosis and leishmaniasis are important human pathogens.

Malarial parasites that are resistant to the drugs that are currently available to infections are common and this has led to increased efforts to develop new drugs. Resistance to recently developed drugs such as artemisinin has also been reported. The problem of drug resistance in malaria has driven efforts to develop vaccines.

Trypanosomes are parasitic protozoa that cause African trypanosomiasis and Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). There are no vaccines to prevent these infections so drugs such as pentamidine and suramin, benznidazole and nifurtimox are used to treat infections. These drugs are effective but infections caused by resistant parasites have been reported.

Leishmaniasis is caused by protozoa and is an important public health problem worldwide, especially in sub-tropical and tropical countries. Drug resistance has "become a major concern".

History

The 1950s to 1970s represented the golden age of antibiotic discovery, where countless new classes of antibiotics were discovered to treat previously incurable diseases such as tuberculosis and syphilis. However, since that time the discovery of new classes of antibiotics has been almost nonexistent, and represents a situation that is especially problematic considering the resiliency of bacteria shown over time and the continued misuse and overuse of antibiotics in treatment.

The phenomenon of antimicrobial resistance caused by overuse of antibiotics was predicted as early as 1945 by Alexander Fleming who said "The time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops. Then there is the danger that the ignorant man may easily under-dose himself and by exposing his microbes to nonlethal quantities of the drug make them resistant." Without the creation of new and stronger antibiotics an era where common infections and minor injuries can kill, and where complex procedures such as surgery and chemotherapy become too risky, is a very real possibility. Antimicrobial resistance threatens the world as we know it, and can lead to epidemics of enormous proportions if preventive actions are not taken. In this day and age current antimicrobial resistance leads to longer hospital stays, higher medical costs, and increased mortality.

Society and culture

Since the mid-1980s pharmaceutical companies have invested in medications for cancer or chronic disease that have greater potential to make money and have "de-emphasized or dropped development of antibiotics". On 20 January 2016 at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, more than "80 pharmaceutical and diagnostic companies" from around the world called for "transformational commercial models" at a global level to spur research and development on antibiotics and on the "enhanced use of diagnostic tests that can rapidly identify the infecting organism".

Legal frameworks

Some global health scholars have argued that a global, legal framework is needed to prevent and control antimicrobial resistance. For instance, binding global policies could be used to create antimicrobial use standards, regulate antibiotic marketing, and strengthen global surveillance systems. Ensuring compliance of involved parties is a challenge. Global antimicrobial resistance policies could take lessons from the environmental sector by adopting strategies that have made international environmental agreements successful in the past such as: sanctions for non-compliance, assistance for implementation, majority vote decision-making rules, an independent scientific panel, and specific commitments.

United States

For the United States 2016 budget, U.S. president Barack Obama proposed to nearly double the amount of federal funding to "combat and prevent" antibiotic resistance to more than $1.2 billion. Many international funding agencies like USAID, DFID, SIDA and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation have pledged money for developing strategies to counter antimicrobial resistance.

On 27 March 2015, the White House released a comprehensive plan to address the increasing need for agencies to combat the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The Task Force for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria developed The National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria with the intent of providing a roadmap to guide the US in the antibiotic resistance challenge and with hopes of saving many lives. This plan outlines steps taken by the Federal government over the next five years needed in order to prevent and contain outbreaks of antibiotic-resistant infections; maintain the efficacy of antibiotics already on the market; and to help to develop future diagnostics, antibiotics, and vaccines.

The Action Plan was developed around five goals with focuses on strengthening health care, public health veterinary medicine, agriculture, food safety and research, and manufacturing. These goals, as listed by the White House, are as follows:

- Slow the Emergence of Resistant Bacteria and Prevent the Spread of Resistant Infections

- Strengthen National One-Health Surveillance Efforts to Combat Resistance

- Advance Development and use of Rapid and Innovative Diagnostic Tests for Identification and Characterization of Resistant Bacteria

- Accelerate Basic and Applied Research and Development for New Antibiotics, Other Therapeutics, and Vaccines

- Improve International Collaboration and Capacities for Antibiotic Resistance Prevention, Surveillance, Control and Antibiotic Research and Development

The following are goals set to meet by 2020:

- Establishment of antimicrobial programs within acute care hospital settings

- Reduction of inappropriate antibiotic prescription and use by at least 50% in outpatient settings and 20% inpatient settings

- Establishment of State Antibiotic Resistance (AR) Prevention Programs in all 50 states

- Elimination of the use of medically important antibiotics for growth promotion in food-producing animals.

United Kingdom

Public Health England reported that the total number of antibiotic resistant infections in England rose by 9% from 55,812 in 2017 to 60,788 in 2018, but antibiotic consumption had fallen by 9% from 20.0 to 18.2 defined daily doses per 1,000 inhabitants per day between 2014 and 2018.

Policies

According to World Health Organization, policymakers can help tackle resistance by strengthening resistance-tracking and laboratory capacity and by regulating and promoting the appropriate use of medicines. Policymakers and industry can help tackle resistance by: fostering innovation and research and development of new tools; and promoting cooperation and information sharing among all stakeholders.

Further research

Rapid viral testing

Clinical investigation to rule out bacterial infections are often done for patients with pediatric acute respiratory infections. Currently it is unclear if rapid viral testing affects antibiotic use in children.

Vaccines

Microorganisms usually do not develop resistance to vaccines because vaccines reduce the spread of the infection and target the pathogen in multiple ways in the same host and possibly in different ways between different hosts. Furthermore, if the use of vaccines increases, there is evidence that antibiotic resistant strains of pathogens will decrease; the need for antibiotics will naturally decrease as vaccines prevent infection before it occurs. However, there are well documented cases of vaccine resistance, although these are usually much less of a problem than antimicrobial resistance.

While theoretically promising, antistaphylococcal vaccines have shown limited efficacy, because of immunological variation between Staphylococcus species, and the limited duration of effectiveness of the antibodies produced. Development and testing of more effective vaccines is underway.

Two registrational trials have evaluated vaccine candidates in active immunization strategies against S. aureus infection. In a phase II trial, a bivalent vaccine of capsulat protein 5 & 8 was tested in 1804 hemodialysis patients with a primary fistula or synthetic graft vascular access. After 40 weeks following vaccination a protective effect was seen against S. aureus bacteremia, but not at 54 weeks following vaccination. Based on these results, a second trial was conducted which failed to show efficacy.

Merck tested V710, a vaccine targeting IsdB, in a blinded randomized trial in patients undergoing median sternotomy. The trial was terminated after a higher rate of multiorgan system failure–related deaths was found in the V710 recipients. Vaccine recipients who developed S. aureus infection were 5 times more likely to die than control recipients who developed S. aureus infection.

Numerous investigators have suggested that a multiple-antigen vaccine would be more effective, but a lack of biomarkers defining human protective immunity keep these proposals in the logical, but strictly hypothetical arena.

Alternating therapy

Alternating therapy is a proposed method in which two or three antibiotics are taken in a rotation versus taking just one antibiotic such that bacteria resistant to one antibiotic are killed when the next antibiotic is taken. Studies have found that this method reduces the rate at which antibiotic resistant bacteria emerge in vitro relative to a single drug for the entire duration.

Studies have found that bacteria that evolve antibiotic resistance towards one group of antibiotic may become more sensitive to others. This phenomenon can be used to select against resistant bacteria using an approach termed collateral sensitivity cycling, which has recently been found to be relevant in developing treatment strategies for chronic infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Development of new drugs

Since the discovery of antibiotics, research and development (R&D) efforts have provided new drugs in time to treat bacteria that became resistant to older antibiotics, but in the 2000s there has been concern that development has slowed enough that seriously ill people may run out of treatment options. Another concern is that doctors may become reluctant to perform routine surgeries because of the increased risk of harmful infection. Backup treatments can have serious side-effects; for example, treatment of multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis can cause deafness or psychological disability. The potential crisis at hand is the result of a marked decrease in industry R&D. Poor financial investment in antibiotic research has exacerbated the situation. The pharmaceutical industry has little incentive to invest in antibiotics because of the high risk and because the potential financial returns are less likely to cover the cost of development than for other pharmaceuticals. In 2011, Pfizer, one of the last major pharmaceutical companies developing new antibiotics, shut down its primary research effort, citing poor shareholder returns relative to drugs for chronic illnesses. However, small and medium-sized pharmaceutical companies are still active in antibiotic drug research. In particular, apart from classical synthetic chemistry methodologies, researchers have developed a combinatorial synthetic biology platform on single cell level in a high-throughput screening manner to diversify novel lanthipeptides.

In the United States, drug companies and the administration of President Barack Obama had been proposing changing the standards by which the FDA approves antibiotics targeted at resistant organisms.

On 18 September 2014 Obama signed an executive order to implement the recommendations proposed in a report by the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) which outlines strategies to stream-line clinical trials and speed up the R&D of new antibiotics. Among the proposals:

- Create a 'robust, standing national clinical trials network for antibiotic testing' which will promptly enroll patients once identified to be suffering from dangerous bacterial infections. The network will allow testing multiple new agents from different companies simultaneously for their safety and efficacy.

- Establish a 'Special Medical Use (SMU)' pathway for FDA to approve new antimicrobial agents for use in limited patient populations, shorten the approval timeline for new drug so patients with severe infections could benefit as quickly as possible.

- Provide economic incentives, especially for development of new classes of antibiotics, to offset the steep R&D costs which drive away the industry to develop antibiotics.

Biomaterials

Using antibiotic-free alternatives in bone infection treatment may help decrease the use of antibiotics and thus antimicrobial resistance. The bone regeneration material bioactive glass S53P4 has shown to effectively inhibit the bacterial growth of up to 50 clinically relevant bacteria including MRSA and MRSE.

Nanomaterials

During the last decades, copper and silver nanomaterials have demonstrated appealing features for the development of a new family of antimicrobial agents.

Rediscovery of ancient treatments

Similar to the situation in malaria therapy, where successful treatments based on ancient recipes have been found, there has already been some success in finding and testing ancient drugs and other treatments that are effective against AMR bacteria.

Rapid diagnostics

Distinguishing infections requiring antibiotics from self-limiting ones is clinically challenging. In order to guide appropriate use of antibiotics and prevent the evolution and spread of antimicrobial resistance, diagnostic tests that provide clinicians with timely, actionable results are needed.

Acute febrile illness is a common reason for seeking medical care worldwide and a major cause of morbidity and mortality. In areas with decreasing malaria incidence, many febrile patients are inappropriately treated for malaria, and in the absence of a simple diagnostic test to identify alternative causes of fever, clinicians presume that a non-malarial febrile illness is most likely a bacterial infection, leading to inappropriate use of antibiotics. Multiple studies have shown that the use of malaria rapid diagnostic tests without reliable tools to distinguish other fever causes has resulted in increased antibiotic use.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) can help practitioners avoid prescribing unnecessary antibiotics in the style of precision medicine, and help them prescribe effective antibiotics, but with the traditional approach it could take 12 to 48 hours. Rapid testing, possible from molecular diagnostics innovations, is defined as "being feasible within an 8-h working shift". Progress has been slow due to a range of reasons including cost and regulation.

Optical techniques such as phase contrast microscopy in combination with single-cell analysis are another powerful method to monitor bacterial growth. In 2017, scientists from Sweden published a method that applies principles of microfluidics and cell tracking, to monitor bacterial response to antibiotics in less than 30 minutes overall manipulation time. Recently, this platform has been advanced by coupling microfluidic chip with optical tweezing in order to isolate bacteria with altered phenotype directly from the analytical matrix.

Phage therapy

Phage therapy is the therapeutic use of bacteriophages to treat pathogenic bacterial infections. Phage therapy has many potential applications in human medicine as well as dentistry, veterinary science, and agriculture.

Phage therapy relies on the use of naturally-occurring bacteriophages to infect and lyse bacteria at the site of infection in a host. Due to current advances in genetics and biotechnology these bacteriophages can possibly be manufactured to treat specific infections. Phages can be bioengineered to target multidrug-resistant bacterial infections, and their use involves the added benefit of preventing the elimination of beneficial bacteria in the human body. Phages destroy bacterial cell walls and membrane through the use of lytic proteins which kill bacteria by making many holes from the inside out. Bacteriophages can even possess the ability to digest the biofilm that many bacteria develop that protect them from antibiotics in order to effectively infect and kill bacteria. Bioengineering can play a role in creating successful bacteriophages.

Understanding the mutual interactions and evolutions of bacterial and phage populations in the environment of a human or animal body is essential for rational phage therapy.

Bacteriophagics are used against antibiotic resistant bacteria in Georgia (George Eliava Institute) and in one institute in Wrocław, Poland. Bacteriophage cocktails are common drugs sold over the counter in pharmacies in eastern countries. In Belgium, four patients with severe musculoskeletal infections received bacteriophage therapy with concomitant antibiotics. After a single course of phage therapy, no recurrence of infection occurred and no severe side-effects related to the therapy were detected.