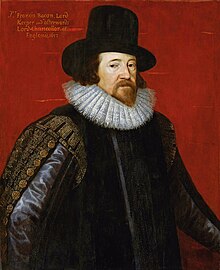

The Viscount St Alban | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Paul van Somer I, 1617 | |

| Lord High Chancellor of England | |

| In office 7 March 1617 – 3 May 1621 | |

| Monarch | James I |

| Preceded by | Sir Thomas Egerton |

| Succeeded by | John Williams |

| Attorney General of England and Wales | |

| In office 26 October 1613 – 7 March 1617 | |

| Monarch | James I |

| Preceded by | Sir Henry Hobart |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Yelverton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Francis Bacon 22 January 1561 The Strand, London, England |

| Died | 9 April 1626 (aged 65) Highgate, Middlesex, England |

| Resting place | St. Michael's Church, St. Albans |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Parents |

|

| Education |

|

| Notable work | Works by Francis Bacon |

| Signature | |

Philosophy career | |

| Other names | Lord Verulam |

Notable work | Novum Organum |

| Era | |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Empiricism |

Main interests | |

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban Kt, PC, QC (/ˈbeɪkən/; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and as Lord Chancellor of England. His works are seen as developing the scientific method and remained influential through the scientific revolution.

Bacon has been called the father of empiricism. He argued for the possibility of scientific knowledge based only upon inductive reasoning and careful observation of events in nature. Most importantly, he argued science could be achieved by the use of a sceptical and methodical approach whereby scientists aim to avoid misleading themselves. Although his most specific proposals about such a method, the Baconian method, did not have long-lasting influence, the general idea of the importance and possibility of a sceptical methodology makes Bacon the father of the scientific method. This method was a new rhetorical and theoretical framework for science, whose practical details are still central to debates on science and methodology.

Francis Bacon was a patron of libraries and developed a system for cataloguing books under three categories – history, poetry, and philosophy – which could further be divided into specific subjects and subheadings. About books he is credited with saying, "Some books are to be tasted; others swallowed; and some few to be chewed and digested." Bacon was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he rigorously followed the medieval curriculum, largely in Latin.

Bacon was the first recipient of the Queen's counsel designation, conferred in 1597 when Elizabeth I of England reserved him as her legal advisor. After the accession of James VI and I in 1603, Bacon was knighted, then created Baron Verulam in 1618 and Viscount St Alban in 1621.

He had no heirs and so both titles became extinct on his death in 1626 at the age of 65. He died of pneumonia, with one account by John Aubrey stating that he had contracted it while studying the effects of freezing on meat preservation. He is buried at St Michael's Church, St Albans, Hertfordshire.

Biography

Early life

Francis Bacon was born on 22 January 1561 at York House near the Strand in London, the son of Sir Nicholas Bacon (Lord Keeper of the Great Seal) by his second wife, Anne (Cooke) Bacon, the daughter of the noted Renaissance humanist Anthony Cooke. His mother's sister was married to William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, making Burghley Bacon's uncle.

Biographers believe that Bacon was educated at home in his early years owing to poor health, which would plague him throughout his life. He received tuition from John Walsall, a graduate of Oxford with a strong leaning toward Puritanism. He went up to Trinity College at the University of Cambridge on 5 April 1573 at the age of 12, living for three years there, together with his older brother Anthony Bacon under the personal tutelage of Dr John Whitgift, future Archbishop of Canterbury. Bacon's education was conducted largely in Latin and followed the medieval curriculum. It was at Cambridge that Bacon first met Queen Elizabeth, who was impressed by his precocious intellect, and was accustomed to calling him "The young lord keeper".

His studies brought him to the belief that the methods and results of science as then practised were erroneous. His reverence for Aristotle conflicted with his rejection of Aristotelian philosophy, which seemed to him barren, argumentative and wrong in its objectives.

On 27 June 1576, he and Anthony entered de societate magistrorum at Gray's Inn. A few months later, Francis went abroad with Sir Amias Paulet, the English ambassador at Paris, while Anthony continued his studies at home. The state of government and society in France under Henry III afforded him valuable political instruction. For the next three years he visited Blois, Poitiers, Tours, Italy, and Spain. During his travels, Bacon studied language, statecraft, and civil law while performing routine diplomatic tasks. On at least one occasion he delivered diplomatic letters to England for Walsingham, Burghley, Leicester, and for the queen.

The sudden death of his father in February 1579 prompted Bacon to return to England. Sir Nicholas had laid up a considerable sum of money to purchase an estate for his youngest son, but he died before doing so, and Francis was left with only a fifth of that money. Having borrowed money, Bacon got into debt. To support himself, he took up his residence in law at Gray's Inn in 1579, his income being supplemented by a grant from his mother Lady Anne of the manor of Marks near Romford in Essex, which generated a rent of £46.

Parliamentarian

Bacon stated that he had three goals: to uncover truth, to serve his country, and to serve his church. He sought achieve these goals by seeking a prestigious post. In 1580, through his uncle, Lord Burghley, he applied for a post at court that might enable him to pursue a life of learning, but his application failed. For two years he worked quietly at Gray's Inn, until he was admitted as an outer barrister in 1582.

His parliamentary career began when he was elected MP for Bossiney, Cornwall, in a by-election in 1581. In 1584 he took his seat in Parliament for Melcombe in Dorset, and in 1586 for Taunton. At this time, he began to write on the condition of parties in the church, as well as on the topic of philosophical reform in the lost tract Temporis Partus Maximus. Yet he failed to gain a position that he thought would lead him to success. He showed signs of sympathy to Puritanism, attending the sermons of the Puritan chaplain of Gray's Inn and accompanying his mother to the Temple Church to hear Walter Travers. This led to the publication of his earliest surviving tract, which criticized the English church's suppression of the Puritan clergy. In the Parliament of 1586, he openly urged execution for the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots.

About this time, he again approached his powerful uncle for help; this move was followed by his rapid progress at the bar. He became a bencher in 1586 and was elected a Reader in 1587, delivering his first set of lectures in Lent the following year. In 1589, he received the valuable appointment of reversion to the Clerkship of the Star Chamber, although he did not formally take office until 1608; the post was worth £1,600 a year.

In 1588 he became MP for Liverpool and then for Middlesex in 1593. He later sat three times for Ipswich (1597, 1601, 1604) and once for Cambridge University (1614).

He became known as a liberal-minded reformer, eager to amend and simplify the law. Though a friend of the crown, he opposed feudal privileges and dictatorial powers. He spoke against religious persecution. He struck at the House of Lords in its usurpation of the Money Bills. He advocated for the union of England and Scotland, which made him a significant influence toward the consolidation of the United Kingdom; and he later would advocate for the integration of Ireland into the Union. Closer constitutional ties, he believed, would bring greater peace and strength to these countries.

Final years of the Queen's reign

Bacon soon became acquainted with the 2nd Earl of Essex, Queen Elizabeth's favourite. By 1591 he acted as the earl's confidential adviser.

In 1592 he was commissioned to write a tract in response to the Jesuit Robert Parson's anti-government polemic, which he titled Certain Observations Made upon a Libel, identifying England with the ideals of democratic Athens against the belligerence of Spain.

Bacon took his third parliamentary seat for Middlesex when in February 1593 Elizabeth summoned Parliament to investigate a Roman Catholic plot against her. Bacon's opposition to a bill that would levy triple subsidies in half the usual time offended the Queen: opponents accused him of seeking popularity, and for a time the Court excluded him from favour.

When the office of Attorney General fell vacant in 1594, Lord Essex's influence was not enough to secure the position for Bacon and it was given to Sir Edward Coke. Likewise, Bacon failed to secure the lesser office of Solicitor General in 1595, the Queen pointedly snubbing him by appointing Sir Thomas Fleming instead. To console him for these disappointments, Essex presented him with a property at Twickenham, which Bacon subsequently sold for £1,800.

In 1597 Bacon became the first Queen's Counsel designate, when Queen Elizabeth reserved him as her legal counsel. In 1597, he was also given a patent, giving him precedence at the Bar. Despite his designations, he was unable to gain the status and notoriety of others. In a plan to revive his position he unsuccessfully courted the wealthy young widow Lady Elizabeth Hatton. His courtship failed after she broke off their relationship upon accepting marriage to Sir Edward Coke, a further spark of enmity between the men. In 1598 Bacon was arrested for debt. Afterward, however, his standing in the Queen's eyes improved. Gradually, Bacon earned the standing of one of the learned counsels. His relationship with the Queen further improved when he severed ties with Essex—a shrewd move, as Essex would be executed for treason in 1601.

With others, Bacon was appointed to investigate the charges against Essex. A number of Essex's followers confessed that Essex had planned a rebellion against the Queen. Bacon was subsequently a part of the legal team headed by the Attorney General Sir Edward Coke at Essex's treason trial. After the execution, the Queen ordered Bacon to write the official government account of the trial, which was later published as A DECLARATION of the Practices and Treasons attempted and committed by Robert late Earle of Essex and his Complices, against her Majestie and her Kingdoms ... after Bacon's first draft was heavily edited by the Queen and her ministers.

According to his personal secretary and chaplain, William Rawley, as a judge Bacon was always tender-hearted, "looking upon the examples with the eye of severity, but upon the person with the eye of pity and compassion". And also that "he was free from malice", "no revenger of injuries", and "no defamer of any man".

James I comes to the throne

The succession of James I brought Bacon into greater favour. He was knighted in 1603. In another shrewd move, Bacon wrote his Apologies in defense of his proceedings in the case of Essex, as Essex had favoured James to succeed to the throne.

The following year, during the course of the uneventful first parliament session, Bacon married Alice Barnham. In June 1607 he was at last rewarded with the office of solicitor general and in 1608 he began working as the Clerkship of the Star Chamber. Despite a generous income, old debts still could not be paid. He sought further promotion and wealth by supporting King James and his arbitrary policies.

In 1610 the fourth session of James's first parliament met. Despite Bacon's advice to him, James and the Commons found themselves at odds over royal prerogatives and the king's embarrassing extravagance. The House was finally dissolved in February 1611. Throughout this period Bacon managed to stay in the favor of the king while retaining the confidence of the Commons.

In 1613 Bacon was finally appointed attorney general, after advising the king to shuffle judicial appointments. As attorney general, Bacon, by his zealous efforts—which included torture—to obtain the conviction of Edmund Peacham for treason, raised legal controversies of high constitutional importance; and successfully prosecuted Robert Carr, 1st Earl of Somerset, and his wife, Frances Howard, Countess of Somerset, for murder in 1616. The so-called Prince's Parliament of April 1614 objected to Bacon's presence in the seat for Cambridge and to the various royal plans that Bacon had supported. Although he was allowed to stay, parliament passed a law that forbade the attorney general to sit in parliament. His influence over the king had evidently inspired resentment or apprehension in many of his peers. Bacon, however, continued to receive the King's favour, which led to his appointment in March 1617 as temporary Regent of England (for a period of a month), and in 1618 as Lord Chancellor. On 12 July 1618 the king created Bacon Baron Verulam, of Verulam, in the Peerage of England; he then became known as Francis, Lord Verulam.

Bacon continued to use his influence with the king to mediate between the throne and Parliament, and in this capacity he was further elevated in the same peerage, as Viscount St Alban, on 27 January 1621.

Lord Chancellor and public disgrace

Bacon's public career ended in disgrace in 1621. After he fell into debt, a parliamentary committee on the administration of the law charged him with 23 separate counts of corruption. His lifelong enemy, Sir Edward Coke, who had instigated these accusations, was one of those appointed to prepare the charges against the chancellor. To the lords, who sent a committee to enquire whether a confession was really his, he replied, "My lords, it is my act, my hand, and my heart; I beseech your lordships to be merciful to a broken reed." He was sentenced to a fine of £40,000 and committed to the Tower of London at the king's pleasure; the imprisonment lasted only a few days and the fine was remitted by the king. More seriously, parliament declared Bacon incapable of holding future office or sitting in parliament. He narrowly escaped undergoing degradation, which would have stripped him of his titles of nobility. Subsequently, the disgraced viscount devoted himself to study and writing.

There seems little doubt that Bacon had accepted gifts from litigants, but this was an accepted custom of the time and not necessarily evidence of deeply corrupt behaviour. While acknowledging that his conduct had been lax, he countered that he had never allowed gifts to influence his judgement and, indeed, he had on occasion given a verdict against those who had paid him. He even had an interview with King James in which he assured:

The law of nature teaches me to speak in my own defence: With respect to this charge of bribery I am as innocent as any man born on St. Innocents Day. I never had a bribe or reward in my eye or thought when pronouncing judgment or order... I am ready to make an oblation of myself to the King

— 17 April 1621

He also wrote the following to Buckingham:

My mind is calm, for my fortune is not my felicity. I know I have clean hands and a clean heart, and I hope a clean house for friends or servants; but Job himself, or whoever was the justest judge, by such hunting for matters against him as hath been used against me, may for a time seem foul, especially in a time when greatness is the mark and accusation is the game.

The true reason for his acknowledgement of guilt is the subject of debate, but some authors speculate that it may have been prompted by his sickness, or by a view that through his fame and the greatness of his office he would be spared harsh punishment. He may even have been blackmailed, with a threat to charge him with sodomy, into confession.

The British jurist Basil Montagu wrote in Bacon's defense, concerning the episode of his public disgrace:

Bacon has been accused of servility, of dissimulation, of various base motives, and their filthy brood of base actions, all unworthy of his high birth, and incompatible with his great wisdom, and the estimation in which he was held by the noblest spirits of the age. It is true that there were men in his own time, and will be men in all times, who are better pleased to count spots in the sun than to rejoice in its glorious brightness. Such men have openly libelled him, like Dewes and Weldon, whose falsehoods were detected as soon as uttered, or have fastened upon certain ceremonious compliments and dedications, the fashion of his day, as a sample of his servility, passing over his noble letters to the Queen, his lofty contempt for the Lord Keeper Puckering, his open dealing with Sir Robert Cecil, and with others, who, powerful when he was nothing, might have blighted his opening fortunes for ever, forgetting his advocacy of the rights of the people in the face of the court, and the true and honest counsels, always given by him, in times of great difficulty, both to Elizabeth and her successor. When was a "base sycophant" loved and honoured by piety such as that of Herbert, Tennison, and Rawley, by noble spirits like Hobbes, Ben Jonson, and Selden, or followed to the grave, and beyond it, with devoted affection such as that of Sir Thomas Meautys.

Personal life

Religious beliefs

Bacon was a devout Anglican. He believed that philosophy and the natural world must be studied inductively, but argued that we can only study arguments for the existence of God. Information on his attributes (such as nature, action, and purposes) can only come from special revelation. Bacon also held that knowledge was cumulative, that study encompassed more than a simple preservation of the past. "Knowledge is the rich storehouse for the glory of the Creator and the relief of man's estate," he wrote. In his Essays, he affirms that "a little philosophy inclineth man's mind to atheism, but depth in philosophy bringeth men's minds about to religion."

Bacon's idea of idols of the mind may have self-consciously represented an attempt to Christianize science at the same time as developing a new, reliable scientific method; Bacon gave worship of Neptune as an example of the idola tribus fallacy, hinting at the religious dimensions of his critique of the idols.

Marriage to Alice Barnham

When he was 36, Bacon courted Elizabeth Hatton, a young widow of 20. Reportedly, she broke off their relationship upon accepting marriage to a wealthier man, Bacon's rival, Sir Edward Coke. Years later, Bacon still wrote of his regret that the marriage to Hatton had not taken place.

At the age of 45, Bacon married Alice Barnham, the almost 14-year-old daughter of a well-connected London alderman and MP. Bacon wrote two sonnets proclaiming his love for Alice. The first was written during his courtship and the second on his wedding day, 10 May 1606. When Bacon was appointed lord chancellor, "by special Warrant of the King", Lady Bacon was given precedence over all other Court ladies. Bacon's personal secretary and chaplain, William Rawley, wrote in his biography of Bacon that his marriage was one of "much conjugal love and respect", mentioning a robe of honour that he gave to Alice and which "she wore unto her dying day, being twenty years and more after his death".

However, an increasing number of reports circulated about friction in the marriage, with speculation that this may have been due to Alice's making do with less money than she had once been accustomed to. It was said that she was strongly interested in fame and fortune, and when household finances dwindled, she complained bitterly. Bunten wrote in her Life of Alice Barnham that, upon their descent into debt, she went on trips to ask for financial favours and assistance from their circle of friends. Bacon disinherited her upon discovering her secret romantic relationship with Sir John Underhill. He subsequently rewrote his will, which had previously been very generous—leaving her lands, goods, and income—and instead revoked it all.

Sexuality

Several authors believe that, despite his marriage, Bacon was primarily attracted to men. Forker, for example, has explored the "historically documentable sexual preferences" of both Francis Bacon and King James I and concluded they were both oriented to "masculine love", a contemporary term that "seems to have been used exclusively to refer to the sexual preference of men for members of their own gender."

The well-connected antiquary John Aubrey noted in his Brief Lives concerning Bacon, "He was a Pederast. His Ganimeds and Favourites tooke Bribes". ("Pederast" in Renaissance diction meant generally "homosexual" rather than specifically a lover of minors; "ganimed" derives from the mythical prince abducted by Zeus to be his cup-bearer and bed warmer.)

The Jacobean antiquarian, Sir Simonds D'Ewes (Bacon's fellow Member of Parliament) implied there had been a question of bringing him to trial for buggery, which his brother Anthony Bacon had also been charged with.

In his Autobiography and Correspondence, in the diary entry for 3 May 1621, the date of Bacon's censure by Parliament, D'Ewes describes Bacon's love for his Welsh serving-men, in particular Godrick, a "very effeminate-faced youth" whom he calls "his catamite and bedfellow".

This conclusion has been disputed by others, who point to lack of consistent evidence, and consider the sources to be more open to interpretation. Publicly, at least, Bacon distanced himself from the idea of homosexuality. In his New Atlantis, he described his utopian island as being "the chastest nation under heaven", and "as for masculine love, they have no touch of it".

Death

On 9 April 1626, Francis Bacon died of pneumonia while at Arundel mansion at Highgate outside London. An influential account of the circumstances of his death was given by John Aubrey's Brief Lives. Aubrey's vivid account, which portrays Bacon as a martyr to experimental scientific method, had him journeying to High-gate through the snow with the King's physician when he is suddenly inspired by the possibility of using the snow to preserve meat:

They were resolved they would try the experiment presently. They alighted out of the coach and went into a poor woman's house at the bottom of Highgate hill, and bought a fowl, and made the woman exenterate it.

After stuffing the fowl with snow, Bacon contracted a fatal case of pneumonia. Some people, including Aubrey, consider these two contiguous, possibly coincidental events as related and causative of his death:

The Snow so chilled him that he immediately fell so extremely ill, that he could not return to his Lodging … but went to the Earle of Arundel's house at Highgate, where they put him into … a damp bed that had not been layn-in … which gave him such a cold that in 2 or 3 days as I remember Mr Hobbes told me, he died of Suffocation.

Aubrey has been criticized for his evident credulousness in this and other works; on the other hand, he knew Thomas Hobbes, Bacon's fellow-philosopher and friend. Being unwittingly on his deathbed, the philosopher dictated his last letter to his absent host and friend Lord Arundel:

My very good Lord,—I was likely to have had the fortune of Caius Plinius the elder, who lost his life by trying an experiment about the burning of Mount Vesuvius; for I was also desirous to try an experiment or two touching the conservation and in-duration of bodies. As for the experiment itself, it succeeded excellently well; but in the journey between London and High-gate, I was taken with such a fit of casting as I know not whether it were the Stone, or some surfeit or cold, or indeed a touch of them all three. But when I came to your Lordship's House, I was not able to go back, and therefore was forced to take up my lodging here, where your housekeeper is very careful and diligent about me, which I assure myself your Lordship will not only pardon towards him, but think the better of him for it. For indeed your Lordship's House was happy to me, and I kiss your noble hands for the welcome which I am sure you give me to it. I know how unfit it is for me to write with any other hand than mine own, but by my troth my fingers are so disjointed with sickness that I cannot steadily hold a pen.

Another account appears in a biography by William Rawley, Bacon's personal secretary and chaplain:

He died on the ninth day of April in the year 1626, in the early morning of the day then celebrated for our Savior's resurrection, in the sixty-sixth year of his age, at the Earl of Arundel's house in Highgate, near London, to which place he casually repaired about a week before; God so ordaining that he should die there of a gentle fever, accidentally accompanied with a great cold, whereby the defluxion of rheum fell so plentifully upon his breast, that he died by suffocation.

He was buried in St Michael's church in St Albans. At the news of his death, over 30 great minds collected together their eulogies of him, which were then later published in Latin. He left personal assets of about £7,000 and lands that realised £6,000 when sold. His debts amounted to more than £23,000, equivalent to more than £3m at current value.

Philosophy and works

Francis Bacon's philosophy is displayed in the vast and varied writings he left, which might be divided into three great branches:

- Scientific works – in which his ideas for a universal reform of knowledge into scientific methodology and the improvement of mankind's state using the Scientific method are presented.

- Religious and literary works – in which he presents his moral philosophy and theological meditations.

- Juridical works – in which his reforms in English Law are proposed.

Influence and legacy

Science

Bacon's seminal work Novum Organum was influential in the 1630s and 1650s among scholars, in particular Sir Thomas Browne, who in his encyclopedia Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646–72) frequently adheres to a Baconian approach to his scientific enquiries. This book entails the basis of the Scientific Method as a means of observation and induction.

According to Francis Bacon, learning and knowledge all derive from the basis of inductive reasoning. Through his belief of experimental encounters, he theorized that all the knowledge that was necessary to fully understand a concept could be attained using induction. In order to get to the point of an inductive conclusion, one must consider the importance of observing the particulars (specific parts of nature). "Once these particulars have been gathered together, the interpretation of Nature proceeds by sorting them into a formal arrangement so that they may be presented to the understanding." Experimentation is essential to discovering the truths of Nature. When an experiment happens, parts of the tested hypothesis are started to be pieced together, forming a result and conclusion. Through this conclusion of particulars, an understanding of Nature can be formed. Now that an understanding of Nature has been arrived at, an inductive conclusion can be drawn. "For no one successfully investigates the nature of a thing in the thing itself; the inquiry must be enlarged to things that have more in common with it."

Francis Bacon explains how we come to this understanding and knowledge because of this process in comprehending the complexities of nature. "Bacon sees nature as an extremely subtle complexity, which affords all the energy of the natural philosopher to disclose her secrets." Bacon described the evidence and proof revealed through taking a specific example from nature and expanding that example into a general, substantial claim of nature. Once we understand the particulars in nature, we can learn more about it and become surer of things occurring in nature, gaining knowledge and obtaining new information all the while. "It is nothing less than a revival of Bacon's supremely confident belief that inductive methods can provide us with ultimate and infallible answers concerning the laws and nature of the universe." Bacon states that when we come to understand parts of nature, we can eventually understand nature better as a whole because of induction. Because of this, Bacon concludes that all learning and knowledge must be drawn from inductive reasoning.

During the Restoration, Bacon was commonly invoked as a guiding spirit of the Royal Society founded under Charles II in 1660. During the 18th-century French Enlightenment, Bacon's non-metaphysical approach to science became more influential than the dualism of his French contemporary Descartes, and was associated with criticism of the Ancien Régime. In 1733 Voltaire introduced him to a French audience as the "father" of the scientific method, an understanding which had become widespread by the 1750s. In the 19th century his emphasis on induction was revived and developed by William Whewell, among others. He has been reputed as the "Father of Experimental Philosophy".

He also wrote a long treatise on Medicine, History of Life and Death, with natural and experimental observations for the prolongation of life.

One of his biographers, the historian William Hepworth Dixon, states: "Bacon's influence in the modern world is so great that every man who rides in a train, sends a telegram, follows a steam plough, sits in an easy chair, crosses the channel or the Atlantic, eats a good dinner, enjoys a beautiful garden, or undergoes a painless surgical operation, owes him something."

In 1902 Hugo von Hofmannsthal published a fictional letter, known as The Lord Chandos Letter, addressed to Bacon and dated 1603, about a writer who is experiencing a crisis of language.

Although Bacon's works are extremely instrumental, his argument falls short because observation and the scientific method are not completely necessary for everything. Bacon takes the inductive method too far, as seen through one of his aphorisms which says, "Man, being the servant and interpreter of Nature, can do and understand so much only as he has observed in fact or in thought of the course of nature: Beyond this he neither knows anything nor can do anything." As humans, we are capable of more than pure observation and can use deduction to form theories. In fact, we must use deduction because Bacon's pure inductive method is incomplete. Thus, it is not Bacon's ideas alone that form the scientific method we use today. If that were the case, we would not be able to fully understand the observations we make and deduce new theories. Author Ernst Mayr states, "Inductivism had a great vogue in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but it is now clear that a purely inductive approach is quite sterile." Mayr points out that an inductive approach on its own just doesn't work. One could observe an experiment multiple times, but still be unable to make generalizations and correctly understand the knowledge. Bacon's inductive method is beneficial, but incomplete and leaves gaps.

However, when combined with the ideas of Descartes, the gaps are filled in Bacon's inductive method. The "anticipation of nature" as Bacon puts it, connects the information gained from observation, enabling hypotheses and theories to become more effective. Bacon's inductive ideas now have more value. Jurgen Klein, who researched Bacon and analyzed his works, says, "The inductive method helps the human mind to find a way to ascertain truthful knowledge." Klein shows the value that Bacon's method truly brings. It is not a value that stands on its own, for it has holes, but it is a value that supports and strengthens. The inductive method can be seen as a tool used alongside other ideas, such as deduction, which now creates a method which is most effective and used today: the scientific method. The inductive method is more prominent in the scientific method than other ideas, which leads to misconception, but the takeaway is that it has supporting ideas. Francis Bacon's scientific method is extremely influential, but has been developed for its own good, as all great ideas are.

North America

Bacon played a leading role in establishing the British colonies in North America, especially in Virginia, the Carolinas and Newfoundland in northeastern Canada. His government report on "The Virginia Colony" was submitted in 1609. In 1610 Bacon and his associates received a charter from the king to form the Tresurer and the Companye of Adventurers and planter of the Cittye of London and Bristoll for the Collonye or plantacon in Newfoundland, and sent John Guy to found a colony there. Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States, wrote: "Bacon, Locke and Newton. I consider them as the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical and Moral sciences".

In 1910 Newfoundland issued a postage stamp to commemorate Bacon's role in establishing the colony. The stamp describes Bacon as "the guiding spirit in Colonization Schemes in 1610". Moreover, some scholars believe he was largely responsible for the drafting, in 1609 and 1612, of two charters of government for the Virginia Colony. William Hepworth Dixon considered that Bacon's name could be included in the list of Founders of the United States.

Law

Although few of his proposals for law reform were adopted during his lifetime, Bacon's legal legacy was considered by the magazine New Scientist in 1961 as having influenced the drafting of the Napoleonic Code as well as the law reforms introduced by 19th-century British Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel. The historian William Hepworth Dixon referred to the Napoleonic Code as "the sole embodiment of Bacon's thought", saying that Bacon's legal work "has had more success abroad than it has found at home", and that in France "it has blossomed and come into fruit".

Harvey Wheeler attributed to Bacon, in Francis Bacon's Verulamium—the Common Law Template of The Modern in English Science and Culture, the creation of these distinguishing features of the modern common law system:

- using cases as repositories of evidence about the "unwritten law";

- determining the relevance of precedents by exclusionary principles of evidence and logic;

- treating opposing legal briefs as adversarial hypotheses about the application of the "unwritten law" to a new set of facts.

As late as the 18th century some juries still declared the law rather than the facts, but already before the end of the 17th century Sir Matthew Hale explained modern common law adjudication procedure and acknowledged Bacon as the inventor of the process of discovering unwritten laws from the evidences of their applications. The method combined empiricism and inductivism in a new way that was to imprint its signature on many of the distinctive features of modern English society. Paul H. Kocher writes that Bacon is considered by some jurists to be the father of modern Jurisprudence.

Bacon is commemorated with a statue in Gray's Inn, South Square in London where he received his legal training, and where he was elected Treasurer of the Inn in 1608.

More recent scholarship on Bacon's jurisprudence has focused on his advocating torture as a legal recourse for the crown. Bacon himself was not a stranger to the torture chamber; in his various legal capacities in both Elizabeth I's and James I's reigns, Bacon was listed as a commissioner on five torture warrants. In 1613(?), in a letter addressed to King James I on the question of torture's place within English law, Bacon identifies the scope of torture as a means to further the investigation of threats to the state: "In the cases of treasons, torture is used for discovery, and not for evidence." For Bacon, torture was not a punitive measure, an intended form of state repression, but instead offered a modus operandi for the government agent tasked with uncovering acts of treason.

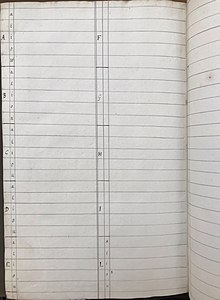

Organization of knowledge

Francis Bacon developed the idea that a classification of knowledge must be universal while handling all possible resources. In his progressive view, humanity would be better if the access to educational resources were provided to the public, hence the need to organise it. His approach to learning reshaped the Western view of knowledge theory from an individual to a social interest.

The original classification proposed by Bacon organised all types of knowledge in three general groups: history, poetry, and philosophy. He did that based on his understanding of how information is processed: memory, imagination, and reason, respectively. His methodical approach to the categorization of knowledge goes hand-in-hand with his principles of scientific methods. Bacon's writings were the starting point for William Torrey Harris's classification system for libraries in the United States by the second half of the 1800s.

The phrase "scientia potentia est" (or "scientia est potentia"), meaning "knowledge is power", is commonly attributed to Bacon: the expression "ipsa scientia potestas est" ("knowledge itself is power") occurs in his Meditationes Sacrae (1597).

Historical debates

Bacon and Shakespeare

The Baconian hypothesis of Shakespearean authorship, first proposed in the mid-19th century, contends that Francis Bacon wrote some or even all of the plays conventionally attributed to William Shakespeare.

Occult theories

Francis Bacon often gathered with the men at Gray's Inn to discuss politics and philosophy, and to try out various theatrical scenes that he admitted writing. Bacon's alleged connection to the Rosicrucians and the Freemasons has been widely discussed by authors and scholars in many books. However, others, including Daphne du Maurier in her biography of Bacon, have argued that there is no substantive evidence to support claims of involvement with the Rosicrucians. Frances Yates does not make the claim that Bacon was a Rosicrucian, but presents evidence that he was nevertheless involved in some of the more closed intellectual movements of his day. She argues that Bacon's movement for the advancement of learning was closely connected with the German Rosicrucian movement, while Bacon's New Atlantis portrays a land ruled by Rosicrucians. He apparently saw his own movement for the advancement of learning to be in conformity with Rosicrucian ideals.

The link between Bacon's work and the Rosicrucians' ideals which Yates allegedly found was the conformity of the purposes expressed by the Rosicrucian Manifestos and Bacon's plan of a "Great Instauration", for the two were calling for a reformation of both "divine and human understanding", as well as both had in view the purpose of mankind's return to the "state before the Fall".

Another major link is said to be the resemblance between Bacon's New Atlantis and the German Rosicrucian Johann Valentin Andreae's Description of the Republic of Christianopolis (1619). Andreae describes a utopic island in which Christian theosophy and applied science ruled, and in which the spiritual fulfilment and intellectual activity constituted the primary goals of each individual, the scientific pursuits being the highest intellectual calling—linked to the achievement of spiritual perfection. Andreae's island also depicts a great advancement in technology, with many industries separated in different zones which supplied the population's needs—which shows great resemblance to Bacon's scientific methods and purposes.

While rejecting occult conspiracy theories surrounding Bacon and the claim Bacon personally identified as a Rosicrucian, intellectual historian Paolo Rossi has argued for an occult influence on Bacon's scientific and religious writing. He argues that Bacon was familiar with early modern alchemical texts and that Bacon's ideas about the application of science had roots in Renaissance magical ideas about science and magic facilitating humanity's domination of nature. Rossi further interprets Bacon's search for hidden meanings in myth and fables in such texts as The Wisdom of the Ancients as succeeding earlier occultist and Neoplatonic attempts to locate hidden wisdom in pre-Christian myths. As indicated by the title of his study, however, Rossi claims Bacon ultimately rejected the philosophical foundations of occultism as he came to develop a form of modern science.

Rossi's analysis and claims have been extended by Jason Josephson-Storm in his study, The Myth of Disenchantment. Josephson-Storm also rejects conspiracy theories surrounding Bacon and does not make the claim that Bacon was an active Rosicrucian. However, he argues that Bacon's "rejection" of magic actually constituted an attempt to purify magic of Catholic, demonic, and esoteric influences and to establish magic as a field of study and application paralleling Bacon's vision of science. Furthermore, Josephson-Storm argues that Bacon drew on magical ideas when developing his experimental method. Josephson-Storm finds evidence that Bacon considered nature a living entity, populated by spirits, and argues Bacon's views on the human domination and application of nature actually depend on his spiritualism and personification of nature.

The Rosicrucian organization AMORC claims that Bacon was the "Imperator" (leader) of the Rosicrucian Order in both England and the European continent, and would have directed it during his lifetime.

Bacon's influence can also be seen on a variety of religious and spiritual authors, and on groups that have utilized his writings in their own belief systems.

Bibliography

Some of the more notable works by Bacon are:

- Essays

- 1st edition with 10 essays (1597)

- 2nd edition with 38 essays (1612)

- 3rd/final edition with 58 essays (1625)

- The Advancement and Proficience of Learning Divine and Human (1605)

- Instauratio magna (The Great Instauration) (1620) – a multi-part work including Distributio operis (Plan of the Work); Novum Organum (New Engine); Parasceve ad historiam naturalem (Preparatory for Natural History) and Catalogus historiarum particularium (Catalogue of Particular Histories)

- De augmentis scientiarum (1623) – an enlargement of The Advancement of Learning translated into Latin

- New Atlantis (1626)