Welfare capitalism is capitalism that includes social welfare policies and/or the practice of businesses providing welfare services to their employees. Welfare capitalism in this second sense, or industrial paternalism, was centered on industries that employed skilled labor and peaked in the mid-20th century.

Today, welfare capitalism is most often associated with the models of capitalism found in Central Mainland and Northern Europe, such as the Nordic model, social market economy and Rhine capitalism. In some cases welfare capitalism exists within a mixed economy, but welfare states can and do exist independently of policies common to mixed economies such as state interventionism and extensive regulation.

Language

"Welfare capitalism" or "welfare corporatism" is somewhat neutral language for what, in other contexts, might be framed as "industrial paternalism", "industrial village", "company town", "representative plan", "industrial betterment", or "company union".

History

In the 19th century, some companies—mostly manufacturers—began offering new benefits for their employees. This began in Britain in the early 19th century and also occurred in other European countries, including France and Germany. These companies sponsored sports teams, established social clubs, and provided educational and cultural activities for workers. Some offered housing as well. Welfare corporatism in the United States developed during the intense industrial development of 1880 to 1900 which was marked by labor disputes and strikes, many violent.

Cooperatives and model villages

One of the first attempts at offering philanthropic welfare to workers was made at the New Lanark mills in Scotland by the social reformer Robert Owen. He became manager and part owner of the mills in 1810, and encouraged by his success in the management of cotton mills in Manchester (see also Quarry Bank Mill), he hoped to conduct New Lanark on higher principles and focus less on commercial profit. The general condition of the people was very unsatisfactory. Many of the workers were steeped in theft and drunkenness, and other vices were common; education and sanitation were neglected and most families lived in one room. The respectable country people refused to submit to the long hours and demoralising drudgery of the mills. Many employers also operated the truck system, whereby payment to the workers was made in part or totally by tokens. These tokens had no value outside the mill owner's "truck shop". The owners were able to supply shoddy goods to the truck shop and charge top prices. A series of "Truck Acts" (1831–1887) eventually stopped this abuse, by making it an offence not to pay employees in common currency.

Owen opened a store where the people could buy goods of sound quality at little more than wholesale cost, and he placed the sale of alcohol under strict supervision. He sold quality goods and passed on the savings from the bulk purchase of goods to the workers. These principles became the basis for the cooperative stores in Britain that continue to operate today. Owen's schemes involved considerable expense, which displeased his partners. Tired of the restrictions on his actions, Owen bought them out in 1813. New Lanark soon became celebrated throughout Europe, with many leading royals, statesmen and reformers visiting the mills. They were astonished to find a clean, healthy industrial environment with a content, vibrant workforce and a prosperous, viable business venture all rolled into one. Owen’s philosophy was contrary to contemporary thinking, but he was able to demonstrate that it was not necessary for an industrial enterprise to treat its workers badly to be profitable. Owen was able to show visitors the village’s excellent housing and amenities, and the accounts showing the profitability of the mills.

Owen and the French socialist Henri de Saint-Simon were the fathers of the utopian socialist movement; they believed that the ills of industrial work relations could be removed by the establishment of small cooperative communities. Boarding houses were built near the factories for the workers' accommodation. These so-called model villages were envisioned as a self-contained community for the factory workers. Although the villages were located close to industrial sites, they were generally physically separated from them and generally consisted of relatively high quality housing, with integrated community amenities and attractive physical environments.

The first such villages were built in the late 18th century, and they proliferated in England in the early 19th century with the establishment of Trowse, Norfolk in 1805 and Blaise Hamlet, Bristol in 1811. In America, boarding houses were built for textile workers in Lowell, Massachusetts in the 1820s. The motive behind these offerings was paternalistic—owners were providing for workers in ways they felt was good for them. These programs did not address the problems of long work hours, unsafe conditions, and employment insecurity that plagued industrial workers during that period, however. Indeed, employers who provided housing in company towns (communities established by employers where stores and housing were run by companies) often faced resentment from workers who chafed at the control owners had over their housing and commercial opportunities. A noted example was Pullman, Illinois—a site of a strike that destroyed the town in 1894. During these years, disputes between employers and workers often turned violent and led to government intervention.

Welfare as a business model

In the early years of the 20th century, however, business leaders began embracing a different approach. The Cadbury family of philanthropists and business entrepreneurs set up the model village at Bournville, England in 1879 for their chocolate making factory. Loyal and hard-working workers were treated with great respect and relatively high wages and good working conditions; Cadbury pioneered pension schemes, joint works committees and a full staff medical service. By 1900, the estate included 313 'Arts and Crafts' cottages and houses; traditional in design but with large gardens and modern interiors, they were designed by the resident architect William Alexander Harvey.

The Cadburys were also concerned with the health and fitness of their workforce, incorporating park and recreation areas into the Bournville village plans and encouraging swimming, walking and indeed all forms of outdoor sports. In the early 1920s, extensive football and hockey pitches were opened together with a grassed running track. Rowheath Pavilion served as the clubhouse and changing rooms for the acres of sports playing fields, several bowling greens, a fishing lake and an outdoor swimming lido, a natural mineral spring forming the source for the lido's healthy waters. The whole area was specifically for the benefit of the Cadbury workers and their families with no charges for the use of any of the sporting facilities by Cadbury employees or their families.

Port Sunlight in Wirral, England was built by the Lever Brothers to accommodate workers in its soap factory in 1888. By 1914, the model village could house a population of 3,500. The garden village had allotments and public buildings including the Lady Lever Art Gallery, a cottage hospital, schools, a concert hall, open air swimming pool, church, and a temperance hotel. Lever introduced welfare schemes, and provided for the education and entertainment of his workforce, encouraging recreation and organisations which promoted art, literature, science or music.

Lever's aims were "to socialise and Christianise business relations and get back to that close family brotherhood that existed in the good old days of hand labour." He claimed that Port Sunlight was an exercise in profit sharing, but rather than share profits directly, he invested them in the village. He said, "It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant—nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation."

In America in the early 20th century, businessmen like George F. Johnson and Henry B. Endicott began to seek new relations with their labor by offering the workers wage incentives and other benefits. The point was to increase productivity by creating good will with employees. When Henry Ford introduced his $5-a-day pay rate in 1914 (when most workers made $11 a week), his goal was to reduce turnover and build a long-term loyal labor force that would have higher productivity. Turnover in manufacturing plants in the U.S. from 1910 to 1919 averaged 100%. Wage incentives and internal promotion opportunities were intended to encourage good attendance and loyalty. This would reduce turnover and improve productivity. The combination of high pay, high efficiency and cheap consumer goods was known as Fordism, and was widely discussed throughout the world.

Led by the railroads and the largest industrial corporations such as the Pullman Car Company, Standard Oil, International Harvester, Ford Motor Company and United States Steel, businesses provided numerous services to its employees, including paid vacations, medical benefits, pensions, recreational facilities, sex education and the like. The railroads, in order to provide places for itinerant trainmen to rest, strongly supported YMCA hotels, and built railroad YMCAs. The Pullman Car Company built an entire model town, Pullman, Illinois. The Seaside Institute is an example of a social club built for the particular benefit of women workers. Most of these programs proliferated after World War I—in the 1920s.

The economic upheaval of the Great Depression in the 1930s brought many of these programs to a halt. Employers cut cultural activities and stopped building recreational facilities as they struggled to stay solvent. It wasn't until after World War II that many of these programs reappeared—and expanded to include more blue-collar workers. Since this time, programs like on-site child care and substance abuse treatment have waxed and waned in use/popularity, but other welfare capitalism components remain. Indeed, in the U.S., the health care system is largely built around employer-sponsored plans.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Germany and Britain created "safety nets" for their citizens, including public welfare and unemployment insurance. These government-operated welfare systems is the sense in which the term 'welfare capitalism' is generally understood today.

Modern welfare capitalism

The 19th century German economist, Gustav von Schmoller, defined welfare capitalism as government provision for the welfare of workers and the public via social legislation. Western Europe, Scandinavia, Canada and Australasia are regions noted for their welfare state provisions, though other countries have publicly financed universal healthcare and other elements of the welfare state as well.

Esping-Andersen categorised three different traditions of welfare provision in his 1990 book The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism; social democracy, Christian democracy (conservatism) and liberalism. Though increasingly criticised, these classifications remain the most commonly used in distinguishing types of modern welfare states, and offer a solid starting point in such analysis.

In Europe

European welfare capitalism is typically endorsed by Christian democrats and social democrats. In contrast to social welfare provisions found in other industrialized countries (especially countries with the Anglo-Saxon model of capitalism), European welfare states provide universal services that benefit all citizens (social democratic welfare state) as opposed to a minimalist model that only caters to the needs of the poor.

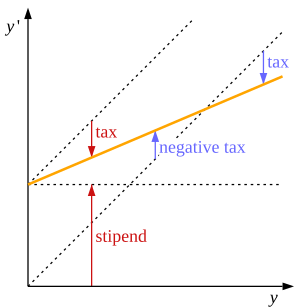

In Northern European countries, welfare capitalism is often combined with social corporatism and national-level collective bargaining arrangements aimed at balancing the power between labor and business. The most prominent example of this system is the Nordic model, which features free and open markets with limited regulation, high concentrations of private ownership in industry, and tax-funded universal welfare benefits for all citizens.

An alternative model of welfare exists in Continental European countries, known as the social market economy or German model, which includes a greater role for government interventionism into the macro-economy but features a less generous welfare state than is found in the Nordic countries.

In France, the welfare state exists alongside a dirigiste mixed economy.

In the United States

Welfare capitalism in the United States refers to industrial relations policies of large, usually non-unionised, companies that have developed internal welfare systems for their employees. Welfare capitalism first developed in the United States in the 1880s and gained prominence in the 1920s.

Promoted by business leaders during a period marked by widespread economic insecurity, social reform activism, and labor unrest, it was based on the idea that Americans should look not to the government or to labor unions but to the workplace benefits provided by private-sector employers for protection against the fluctuations of the market economy. Companies employed these types of welfare policies to encourage worker loyalty, productivity and dedication. Owners feared government intrusion in the Progressive Era, and labor uprisings from 1917 to 1919—including strikes against "benevolent" employers—showed the limits of paternalistic efforts. For owners, the corporation was the most responsible social institution and it was better suited, in their minds, to promoting the welfare of employees than government. Welfare capitalism was their way of heading off unions, communism, and government regulation.

The benefits offered by welfare capitalist employers were often inconsistent and varied widely from firm to firm. They included minimal benefits such as cafeteria plans, company-sponsored sports teams, lunchrooms and water fountains in plants, and company newsletters/magazines—as well as more extensive plans providing retirement benefits, health care, and employee profit-sharing. Examples of companies that have practiced welfare capitalism include Kodak, Sears, and IBM, with the main elements of the employment system in these companies including permanent employment, internal labor markets, extensive security and fringe benefits, and sophisticated communications and employee involvement.

In the 1980s, the philosophy of maximizing shareholder value became dominant, and defined contribution plans such as 401(k)s, replaced guaranteed pensions. The average duration of employment at the same firm also decreased significantly.

Anti-unionism

Welfare capitalism was also used as a way to resist government regulation of markets, independent labor union organizing, and the emergence of a welfare state. Welfare capitalists went to great lengths to quash independent trade union organizing, strikes, and other expressions of labor collectivism—through a combination of violent suppression, worker sanctions, and benefits in exchange for loyalty. Also, employee stock-ownership programs meant to tie workers to the success of companies (and accordingly to management). Workers would then be actual partners with owners—and capitalists themselves. Owners intended these programs to ward off the threat of "Bolshevism" and undermine the appeal of unions.

The least popular of the welfare capitalism programs were the company unions created to stave off labor activism. By offering employees a say in company policies and practices and a means for appealing disputes internally, employers hoped to reduce the lure of unions. They dubbed these employee representation plans "industrial democracy."

Efficacy

In the end, welfare capitalism programs benefited white-collar workers far more than those on the factory floor in the early 20th century. The average annual bonus payouts at U.S. Steel Corporation from 1929 to 1931 were approximately $2,500,000; however, in 1929, $1,623,753 of that went to the president of the company. Real wages for unskilled and low-skilled workers grew little in the 1920s, while long hours in unsafe conditions continued to be the norm. Further, employment instability due to layoffs remained a reality of work life. Welfare capitalism programs rarely worked as intended, company unions only reinforced that authority of management over the terms of employment.

Wage incentives (merit raises and bonuses) often led to a speed-up in production for factory lines. As much as these programs meant to encourage loyalty to the company, this effort was often undermined by continued layoffs and frustrations with working conditions. Employees soured on employee representation plans and cultural activities, but they were eager for opportunities to improve their pay with good work and attendance and to gain benefits like medical care. These programs gave workers new expectations for their employers. They were often disappointed in the execution of them but supported their aims. The post-World War II era saw an expansion of these programs for all workers, and today, these benefits remain part of employment relations in many countries. Recently, however, there has been a trend away from this form of welfare capitalism, as corporations have reduced the portion of compensation paid with health care, and shifted from defined benefit pensions to employee-funded defined contribution plans.