Rational choice theory refers to a set of guidelines that help understand economic and social behaviour. The theory originated in the eighteenth century and can be traced back to political economist and philosopher, Adam Smith. The theory postulates that an individual will perform a cost-benefit analysis to determine whether an option is right for them. It also suggests that an individual's self-driven rational actions will help better the overall economy. Rational choice theory looks at three concepts: rational actors, self interest and the invisible hand.

Rationality can be used as an assumption for the behaviour of individuals in a wide range of contexts outside of economics. It is also used in political science, sociology, and philosophy.

Overview

The basic premise of rational choice theory is that the decisions made by individual actors will collectively produce aggregate social behaviour. The theory also assumes that individuals have preferences out of available choice alternatives. These preferences are assumed to be complete and transitive. Completeness refers to the individual being able to say which of the options they prefer (i.e. individual prefers A over B, B over A or are indifferent to both). Alternatively, transitivity is where the individual weakly prefers option A over B and weakly prefers option B over C, leading to the conclusion that the individual weakly prefers A over C. The rational agent will then perform their own cost-benefit analysis using a variety of criterion to perform their self-determined best choice of action.

One version of rationality is instrumental rationality, which involves achieving a goal using the most cost effective method without reflecting on the worthiness of that goal. Duncan Snidal emphasises that the goals are not restricted to self-regarding, selfish, or material interests. They also include other-regarding, altruistic, as well as normative or ideational goals.

Rational choice theory does not claim to describe the choice process, but rather it helps predict the outcome and pattern of choice. It is consequently assumed that the individual is self-interested or being homo economicus. Here, the individual comes to a decision that maximizes personal advantage by balancing costs and benefits. Proponents of such models, particularly those associated with the Chicago school of economics, do not claim that a model's assumptions are an accurate description of reality, only that they help formulate clear and falsifiable hypotheses. In this view, the only way to judge the success of a hypothesis is empirical tests. To use an example from Milton Friedman, if a theory that says that the behavior of the leaves of a tree is explained by their rationality passes the empirical test, it is seen as successful.

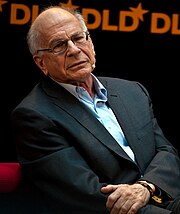

Without explicitly dictating the goal or preferences of the individual, it may be impossible to empirically test or invalidate the rationality assumption. However, the predictions made by a specific version of the theory are testable. In recent years, the most prevalent version of rational choice theory, expected utility theory, has been challenged by the experimental results of behavioral economics. Economists are learning from other fields, such as psychology, and are enriching their theories of choice in order to get a more accurate view of human decision-making. For example, the behavioral economist and experimental psychologist Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2002 for his work in this field.

Rational choice theory has proposed that there are two outcomes of two choices regarding human action. Firstly, the feasible region will be chosen within all the possible and related action. Second, after the preferred option has been chosen, the feasible region that has been selected was picked based on restriction of financial, legal, social, physical or emotional restrictions that the agent is facing. After that, a choice will be made based on the preference order.

The concept of rationality used in rational choice theory is different from the colloquial and most philosophical use of the word. In this sense, "rational" behaviour can refer to "sensible", "predictable", or "in a thoughtful, clear-headed manner." Rational choice theory uses a much more narrow definition of rationality. At its most basic level, behavior is rational if it is goal-oriented, reflective (evaluative), and consistent (across time and different choice situations). This contrasts with behavior that is random, impulsive, conditioned, or adopted by (unevaluative) imitation.

Early neoclassical economists writing about rational choice, including William Stanley Jevons, assumed that agents make consumption choices so as to maximize their happiness, or utility. Contemporary theory bases rational choice on a set of choice axioms that need to be satisfied, and typically does not specify where the goal (preferences, desires) comes from. It mandates just a consistent ranking of the alternatives. Individuals choose the best action according to their personal preferences and the constraints facing them. E.g., there is nothing irrational in preferring fish to meat the first time, but there is something irrational in preferring fish to meat in one instant and preferring meat to fish in another, without anything else having changed.

Actions, assumptions, and individual preferences

The basic premise of rational choice theory is that the decisions made by individual actors will collectively produce aggregate social behaviour. Thus, each individual makes a decision based on their own preferences and the constraints (or choice set) they face.

Rational choice theory can be viewed in different contexts. At an individual level, the theory suggests that the agent will decide on the action (or outcome) they most prefer. If the actions (or outcomes) are evaluated in terms of costs and benefits, the choice with the maximum net benefit will be chosen by the rational individual. Rational behaviour is not solely driven by monetary gain, but can also be driven by emotional motives.

| Part of a series on |

| Utilitarianism |

|---|

The theory can be applied to general settings outside of those identified by costs and benefits. In general, rational decision making entails choosing among all available alternatives the alternative that the individual most prefers. The "alternatives" can be a set of actions ("what to do?") or a set of objects ("what to choose/buy"). In the case of actions, what the individual really cares about are the outcomes that results from each possible action. Actions, in this case, are only an instrument for obtaining a particular outcome.

Formal statement

The available alternatives are often expressed as a set of objects, for example a set of j exhaustive and exclusive actions:

For example, if a person can choose to vote for either Roger or Sara or to abstain, their set of possible alternatives is:

The theory makes two technical assumptions about individuals' preferences over alternatives:

- Completeness – for any two alternatives ai and aj in the set, either ai is preferred to aj, or aj is preferred to ai, or the individual is indifferent between ai and aj. In other words, all pairs of alternatives can be compared with each other.

- Transitivity – if alternative a1 is preferred to a2, and alternative a2 is preferred to a3, then a1 is preferred to a3.

Together these two assumptions imply that given a set of exhaustive and exclusive actions to choose from, an individual can rank the elements of this set in terms of his preferences in an internally consistent way (the ranking constitutes a partial ordering), and the set has at least one maximal element.

The preference between two alternatives can be:

- Strict preference occurs when an individual prefers a1 to a2 and does not view them as equally preferred.

- Weak preference implies that individual either strictly prefers a1 over a2 or is indifferent between them.

- Indifference occurs when an individual neither prefers a1 to a2, nor a2 to a1. Since (by completeness) the individual does not refuse a comparison, they must therefore be indifferent in this case.

Research that took off in the 1980s sought to develop models that drop these assumptions and argue that such behaviour could still be rational, Anand (1993). This work, often conducted by economic theorists and analytical philosophers, suggests ultimately that the assumptions or axioms above are not completely general and might at best be regarded as approximations.

Additional assumptions

- Perfect information: The simple rational choice model above assumes that the individual has full or perfect information about the alternatives, i.e., the ranking between two alternatives involves no uncertainty.

- Choice under uncertainty: In a richer model that involves uncertainty about the how choices (actions) lead to eventual outcomes, the individual effectively chooses between lotteries, where each lottery induces a different probability distribution over outcomes. The additional assumption of independence of irrelevant alternatives then leads to expected utility theory.

- Inter-temporal choice: when decisions affect choices (such as consumption) at different points in time, the standard method for evaluating alternatives across time involves discounting future payoffs.

- Limited cognitive ability: identifying and weighing each alternative against every other may take time, effort, and mental capacity. Recognising the cost that these impose or cognitive limitations of individuals gives rise to theories of bounded rationality.

Alternative theories of human action include such components as Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman's prospect theory, which reflects the empirical finding that, contrary to standard preferences assumed under neoclassical economics, individuals attach extra value to items that they already own compared to similar items owned by others. Under standard preferences, the amount that an individual is willing to pay for an item (such as a drinking mug) is assumed to equal the amount they are willing to be paid in order to part with it. In experiments, the latter price is sometimes significantly higher than the former (but see Plott and Zeiler 2005, Plott and Zeiler 2007 and Klass and Zeiler, 2013). Tversky and Kahneman do not characterize loss aversion as irrational. Behavioral economics includes a large number of other amendments to its picture of human behavior that go against neoclassical assumptions.

Utility maximization

Often preferences are described by their utility function or payoff function. This is an ordinal number that an individual assigns over the available actions, such as:

The individual's preferences are then expressed as the relation between these ordinal assignments. For example, if an individual prefers the candidate Sara over Roger over abstaining, their preferences would have the relation:

A preference relation that as above satisfies completeness, transitivity, and, in addition, continuity, can be equivalently represented by a utility function.

Benefits

The rational choice approach allows preferences to be represented as real-valued utility functions. Economic decision making then becomes a problem of maximizing this utility function, subject to constraints (e.g. a budget). This has many advantages. It provides a compact theory that makes empirical predictions with a relatively sparse model - just a description of the agent's objectives and constraints. Furthermore, optimization theory is a well-developed field of mathematics. These two factors make rational choice models tractable compared to other approaches to choice. Most importantly, this approach is strikingly general. It has been used to analyze not only personal and household choices about traditional economic matters like consumption and savings, but also choices about education, marriage, child-bearing, migration, crime and so on, as well as business decisions about output, investment, hiring, entry, exit, etc. with varying degrees of success.

In the field of political science rational choice theory has been used to help predict human decision making and model for the future; therefore it is useful in creating effective public policy, and enables the government to develop solutions quickly and efficiently.

Despite the empirical shortcomings of rational choice theory, the flexibility and tractability of rational choice models (and the lack of equally powerful alternatives) lead to them still being widely used.

Applications

Rational choice theory has become increasingly employed in social sciences other than economics, such as sociology, evolutionary theory and political science in recent decades. It has had far-reaching impacts on the study of political science, especially in fields like the study of interest groups, elections, behaviour in legislatures, coalitions, and bureaucracy. In these fields, the use of the rational choice theory to explain broad social phenomena is the subject of controversy.

Rational choice theory in politics

The relationship between the rational choice theory and politics takes many forms, whether that be in voter behaviour, the actions of world leaders or even the way that important matters are dealt with.

Voter behaviour shifts significantly thanks to rational theory, which is ingrained in human nature, the most significant of which occurs when there are times of economic trouble. This was assessed in detail by Anthony Downs who concluded that voters were acting on thoughts of higher income as a person ‘votes for whatever party he believes would provide him with the highest utility income from government action’. This is a significant simplification of how the theory influences people's thoughts but makes up a core part of rational theory as a whole. In a more complex fashion, voters will react often radically in times of real economic strife, which can lead to an increase in extremism. The government will be made responsible by the voters and thus they see a need to make a change. Some of the most infamous extremist parties came to power on the back of economic recessions, the most significant being the far right Nazi Party in Germany, who used the hyperinflation at the time to gain power rapidly, as they promised a solution and a scapegoat for the blame. There is a trend to this, as a comprehensive study carried out by three political scientists concluded, as a ‘turn to the right’ occurs and it is clear that it is the work of the rational theory because within ten years the politics returns to a more common state.

Anthony Downs also suggested that voting involves a cost/benefit analysis in order to determine how a person would vote. He argues that someone will vote if B+D>C, where B= The benefit of the voter winning, D= Satisfaction and C being the cost of voting. It is from this that we can determine that parties have moved their policy outlook to be more centric in order to maximise the amount of voters they have for support. This is becoming more and more prevalent with every election as each party tries to appeal to a broader range of voters. This is especially prevalent as there has been a decline in party memberships, meaning that each party has much less guaranteed votes. In the last 10 years there has been a 37% decrease in party memberships, with this trend having started soon after the Second World War. This shows that the electorate a leaning towards making informed, rational decisions as opposed to relying on a pattern of behaviours. Overall the electorate are becoming more inclined to vote based on recency factors in order to protect their interests and maximise their utility.

Meaning Rational Choice Theory has the ability to be used in modelling and forecasting, owing to its nature being derived from economic thought to explain human behaviour. This is useful in politics as the theory can quantify human decision making and behaviour into data that can be interpreted, helping to predict behaviours and outcomes. Therefore enabling the ability to direct and shape political thinking and campaigns, maximizing utility.

As useful as the use of empirical data is in building a clear picture of voting behaviour it doesn't full show all aspects of political decision making whether that be from the electorate or the policy makers. As brings the idea of commitment as a key concept to the behaviour of political agents. That it is not only self interest that is the outcome of personal cost benefit analysis but it is also the idea of shared interests. That the key idea of utility needs to be defined not only as material utility but also as experienced utility, these expansions to classical rational choice theory could then begin to remove the weakness in regards to morals of the agents which it aims to interoperate their actions.

A downfall of rational choice theory in a political sense, is that is the pursuit of individual goals can lead to collectively irrational outcomes. This problem of collective action can disincentivise people to vote. Even though a group of people may have common interests, they also have conflicting ones that cause misalignment within the group and therefore an outcome that does not benefit the group as a whole as people want to pursue their own individual interests. This problem is rooted in Rational Choice theory because of the theories emphasis on the rational agents performing their own cost-benefit analysis to maximize their self-interests.

An example of this can be shown by some of the world’s most troubling problems, such as the climate crisis. Nation states can be seen as rational as they fulfil their own interests of economic growth, however, this economic growth often leads to pollution as increasing a nation’s factors of production takes a toll on the environment. It is irrational for a state to forego this economic growth as the cost of pollution does not entirely fall on them, as one state’s carbon emissions would not entirely affect that state alone, as it impacts elsewhere. This means the benefit of the economic growth outweighs the cost of pollution, according to the theory of Rational Choice. However, If all countries made this rational calculation it would lead to a massive amount of pollution. Making the outcome of a rational choice, a collectively irrational outcome.

Rational choice theory in international relations

Rational choice theory has become one of the major approaches in the study of international relations. Its proponents typically assume that states are the key actors in world politics and that they seek goals such as power, security, or wealth. They have applied rational choice theory to policy issues ranging from international trade and international cooperation to sanctions, arms competition, (nuclear) deterrence, and war.

For example, some scholars have examined how states can make credible threats to deter other states from a (nuclear) attack. Others have explored under what conditions states wage war against each other. Yet others have investigated under what circumstances the threat and imposition of international economic sanctions tend to succeed and when they are likely to fail.

Rational Choice theory in Social Interactions

Rational Choice Theory and Social exchange theory involves looking at all social relations in the form of costs and rewards, both tangible and non tangible.

According to Abell, Rational Choice Theory is "understanding individual actors... as acting, or more likely interacting, in a manner such that they can be deemed to be doing the best they can for themselves, given their objectives, resources, circumstances, as they seem them". Rational Choice Theory has been used to comprehend the complex social phenomena, of which derives from the actions and motivations of an individual. Individuals are often highly motivated by the wants and needs.

By making calculative decisions, it is considered as rational action. Individuals are often making calculative decisions in social situations by weighing out the pros and cons of an action taken towards a person. The decision to act on a rational decision is also dependent on the unforeseen benefits of the friendship. Homan mentions that actions of humans are motivated by punishment or rewards. This reinforcement through punishments or rewards determines the course of action taken by a person in a social situation as well. Individuals are motivated by mutual reinforcement and are also fundamentally motivated by the approval of others. Attaining the approval of others has been a generalized character, along with money, as a means of exchange in both Social and Economic exchanges. In Economic exchanges, it involves the exchange of goods or services. In Social exchange, it is the exchange of approval and certain other valued behaviors.

Rational Choice Theory in this instance, heavily emphasizes the individual's interest as a starting point for making social decisions. Despite differing view points about Rational choice theory, it all comes down to the individual as a basic unit of theory. Even though sharing, cooperation and cultural norms emerge, it all stems from an individual's initial concern about the self.

Social Exchange and Rational Choice Theory both comes down to an individual's efforts to meet their own personal needs and interests through the choices they make. Even though some may be done sincerely for the welfare of others at that point of time, both theories point to the benefits received in return. These returns may be received immediately or in the future, be it tangible or not.

Coleman discussed a number of theories to elaborate on the premises and promises of rational choice theory. One of the concepts that He introduced was Trust. It is where "individuals place trust, in both judgement and performance of others, based on rational considerations of what is best, given the alternatives they confront". In a social situation, there has to be a level of trust among the individuals. He noted that this level of trust is a consideration that an individual takes into concern before deciding on a rational action towards another individual. It affects the social situation as one navigates the risks and benefits of an action. By assessing the possible outcomes or alternatives to an action for another individual, the person is making a calculated decision. In another situation such as making a bet, you are calculating the possible lost and how much can be won. If the chances of winning exceeds the cost of losing, the rational decision would be to place the bet. Therefore, the decision to place trust in another individual involves the same rational calculations that are involved in the decision of making a bet.

Even though rational theory is used in Economics and Social settings, there are some similarities and differences. The concept of reward and reinforcement is parallel to each other while the concept of cost is also parallel to the concept of punishment. However, there is a difference of underlying assumptions in both contexts. In social a social setting, the focus is often on the current or past reinforcements instead of the future although there is no guarantee of immediate tangible or intangible returns from another individual. In Economics, decisions are made with heavier emphasis on future rewards.

Despite having both perspectives differ in focus, they primarily reflect on how individuals make different rational decisions when given an immediate or long-term circumstances to consider in their rational decision making.

Criticism

This theory critically helps us to understand the choices an individual or society makes. Even though some decisions are not entirely rational, it is possible that Rational Choice Theory still helps us to understand the motivations behind it. Moreover, there has been a lot of discourse about Rational Choice Theory. It has often been too individualistic, minimalistic and heavily focused on rational decisions in social actions. Sociologists tend to justify any human action as rational as individuals are solely motivated by the pursuit of self-interest. It does not consider the possibility of pure altruism of a social exchange between individuals.

Criticism

Both the assumptions and the behavioral predictions of rational choice theory have sparked criticism from various camps.

The limits of rationality

As mentioned above, some economists have developed models of bounded rationality, such as Herbert Simon, which hope to be more psychologically plausible without completely abandoning the idea that reason underlies decision-making processes. Simon argues factors such as imperfect information, uncertainty and time constraints all affect and limit our rationality, and therefore our decision making skills. Furthermore his concepts of 'satisficing' and 'optimizing' suggest sometimes because of these factors, we settle for a decision which is good enough, rather than the best decision. Other economists have developed more theories of human decision-making that allow for the roles of uncertainty, institutions, and determination of individual tastes by their socioeconomic environment (cf. Fernandez-Huerga, 2008).

Philosophical critiques

Martin Hollis and Edward J. Nell's 1975 book offers both a philosophical critique of neo-classical economics and an innovation in the field of economic methodology. Further, they outlined an alternative vision to neo-classicism based on a rationalist theory of knowledge. Within neo-classicism, the authors addressed consumer behaviour (in the form of indifference curves and simple versions of revealed preference theory) and marginalist producer behaviour in both product and factor markets. Both are based on rational optimizing behaviour. They consider imperfect as well as perfect markets since neo-classical thinking embraces many market varieties and disposes of a whole system for their classification. However, the authors believe that the issues arising from basic maximizing models have extensive implications for econometric methodology (Hollis and Nell, 1975, p. 2). In particular it is this class of models – rational behavior as maximizing behaviour – which provide support for specification and identification. And this, they argue, is where the flaw is to be found. Hollis and Nell (1975) argued that positivism (broadly conceived) has provided neo-classicism with important support, which they then show to be unfounded. They base their critique of neo-classicism not only on their critique of positivism but also on the alternative they propose, rationalism. Indeed, they argue that rationality is central to neo-classical economics – as rational choice – and that this conception of rationality is misused. Demands are made of it that it cannot fulfill. Ultimately, individuals do not always act rationally or conduct themselves in a utility maximising manner.

Duncan K. Foley (2003, p. 1) has also provided an important criticism of the concept of rationality and its role in economics. He argued that

“Rationality” has played a central role in shaping and establishing the hegemony of contemporary mainstream economics. As the specific claims of robust neoclassicism fade into the history of economic thought, an orientation toward situating explanations of economic phenomena in relation to rationality has increasingly become the touchstone by which mainstream economists identify themselves and recognize each other. This is not so much a question of adherence to any particular conception of rationality, but of taking rationality of individual behavior as the unquestioned starting point of economic analysis.

Foley (2003, p. 9) went on to argue that

The concept of rationality, to use Hegelian language, represents the relations of modern capitalist society one-sidedly. The burden of rational-actor theory is the assertion that ‘naturally’ constituted individuals facing existential conflicts over scarce resources would rationally impose on themselves the institutional structures of modern capitalist society, or something approximating them. But this way of looking at matters systematically neglects the ways in which modern capitalist society and its social relations in fact constitute the ‘rational’, calculating individual. The well-known limitations of rational-actor theory, its static quality, its logical antinomies, its vulnerability to arguments of infinite regress, its failure to develop a progressive concrete research program, can all be traced to this starting-point.

More recently Edward J. Nell and Karim Errouaki (2011, Ch. 1) argued that:

The DNA of neoclassical economics is defective. Neither the induction problem nor the problems of methodological individualism can be solved within the framework of neoclassical assumptions. The neoclassical approach is to call on rational economic man to solve both. Economic relationships that reflect rational choice should be ‘projectible’. But that attributes a deductive power to ‘rational’ that it cannot have consistently with positivist (or even pragmatist) assumptions (which require deductions to be simply analytic). To make rational calculations projectible, the agents may be assumed to have idealized abilities, especially foresight; but then the induction problem is out of reach because the agents of the world do not resemble those of the model. The agents of the model can be abstract, but they cannot be endowed with powers actual agents could not have. This also undermines methodological individualism; if behaviour cannot be reliably predicted on the basis of the ‘rational choices of agents’, a social order cannot reliably follow from the choices of agents.

Empirical critiques

In their 1994 work, Pathologies of Rational Choice Theory, Donald P. Green and Ian Shapiro argue that the empirical outputs of rational choice theory have been limited. They contend that much of the applicable literature, at least in political science, was done with weak statistical methods and that when corrected many of the empirical outcomes no longer hold. When taken in this perspective, rational choice theory has provided very little to the overall understanding of political interaction - and is an amount certainly disproportionately weak relative to its appearance in the literature. Yet, they concede that cutting-edge research, by scholars well-versed in the general scholarship of their fields (such as work on the U.S. Congress by Keith Krehbiel, Gary Cox, and Mat McCubbins) has generated valuable scientific progress.

Methodological critiques

Schram and Caterino (2006) contains a fundamental methodological criticism of rational choice theory for promoting the view that the natural science model is the only appropriate methodology in social science and that political science should follow this model, with its emphasis on quantification and mathematization. Schram and Caterino argue instead for methodological pluralism. The same argument is made by William E. Connolly, who in his work Neuropolitics shows that advances in neuroscience further illuminate some of the problematic practices of rational choice theory.

Sociological critiques

Pierre Bourdieu fiercely opposed rational choice theory as grounded in a misunderstanding of how social agents operate. Bourdieu argued that social agents do not continuously calculate according to explicit rational and economic criteria. According to Bourdieu, social agents operate according to an implicit practical logic—a practical sense—and bodily dispositions. Social agents act according to their "feel for the game" (the "feel" being, roughly, habitus, and the "game" being the field).

Other social scientists, inspired in part by Bourdieu's thinking have expressed concern about the inappropriate use of economic metaphors in other contexts, suggesting that this may have political implications. The argument they make is that by treating everything as a kind of "economy" they make a particular vision of the way an economy works seem more natural. Thus, they suggest, rational choice is as much ideological as it is scientific, which does not in and of itself negate its scientific utility.

Critiques on the basis of evolutionary psychology

An evolutionary psychology perspective suggests that many of the seeming contradictions and biases regarding rational choice can be explained as being rational in the context of maximizing biological fitness in the ancestral environment but not necessarily in the current one. Thus, when living at subsistence level where a reduction of resources may have meant death it may have been rational to place a greater value on losses than on gains. Proponents argue it may also explain differences between groups.

Critiques on the basis of emotion research

Proponents of emotional choice theory criticize the rational choice paradigm by drawing on new findings from emotion research in psychology and neuroscience. They point out that rational choice theory is generally based on the assumption that decision-making is a conscious and reflective process based on thoughts and beliefs. It presumes that people decide on the basis of calculation and deliberation. However, cumulative research in neuroscience suggests that only a small part of the brain's activities operate at the level of conscious reflection. The vast majority of its activities consist of unconscious appraisals and emotions. The significance of emotions in decision-making has generally been ignored by rational choice theory, according to these critics. Moreover, emotional choice theorists contend that the rational choice paradigm has difficulty incorporating emotions into its models, because it cannot account for the social nature of emotions. Even though emotions are felt by individuals, psychologists and sociologists have shown that emotions cannot be isolated from the social environment in which they arise. Emotions are inextricably intertwined with people's social norms and identities, which are typically outside the scope of standard rational choice models. Emotional choice theory seeks to capture not only the social but also the physiological and dynamic character of emotions. It represents a unitary action model to organize, explain, and predict the ways in which emotions shape decision-making.