| Photodynamic therapy | |

|---|---|

Close

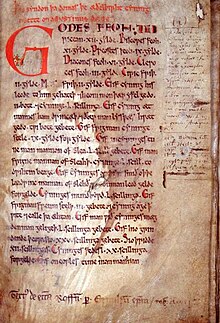

up of surgeons' hands in an operating room with a beam of light

traveling along fiber optics for photodynamic therapy. Its source is a

laser beam which is split at two different stages to create the proper

therapeutic wavelength. A patient is given a photosensitive drug that is

absorbed by cancer cells. During the surgery, the light beam is

positioned at the tumor site, which then activates the drug that kills

the cancer cells, thus photodynamic therapy (PDT). | |

| Other names | photochemotherapy |

Photodynamic therapy (PDT), is a form of phototherapy involving light and a photosensitizing chemical substance, used in conjunction with molecular oxygen to elicit cell death (phototoxicity).

PDT is popularly used in treating acne. It is used clinically to treat a wide range of medical conditions, including wet age-related macular degeneration, psoriasis, atherosclerosis and has shown some efficacy in anti-viral treatments, including herpes. It also treats malignant cancers including head and neck, lung, bladder and particular skin. The technology has also been tested for treatment of prostate cancer, both in a dog model and in human prostate cancer patients.

It is recognised as a treatment strategy that is both minimally invasive and minimally toxic. Other light-based and laser therapies such as laser wound healing and rejuvenation, or intense pulsed light hair removal do not require a photosensitizer. Photosensitisers have been employed to sterilise blood plasma and water in order to remove blood-borne viruses and microbes and have been considered for agricultural uses, including herbicides and insecticides.

Photodynamic therapy's advantages lessen the need for delicate surgery and lengthy recuperation and minimal formation of scar tissue and disfigurement. A side effect is the associated photosensitisation of skin tissue.

Basics

PDT applications involve three components: a photosensitizer, a light source and tissue oxygen. The wavelength of the light source needs to be appropriate for exciting the photosensitizer to produce radicals and/or reactive oxygen species. These are free radicals (Type I) generated through electron abstraction or transfer from a substrate molecule and highly reactive state of oxygen known as singlet oxygen (Type II).

PDT is a multi-stage process. First a photosensitiser with negligible dark toxicity is administered, either systemically or topically, in the absence of light. When a sufficient amount of photosensitiser appears in diseased tissue, the photosensitiser is activated by exposure to light for a specified period. The light dose supplies sufficient energy to stimulate the photosensitiser, but not enough to damage neighbouring healthy tissue. The reactive oxygen kills the target cells.

Reactive oxygen species

In air and tissue, molecular oxygen (O2) occurs in a triplet state, whereas almost all other molecules are in a singlet state. Reactions between triplet and singlet molecules are forbidden by quantum mechanics, making oxygen relatively non-reactive at physiological conditions. A photosensitizer is a chemical compound that can be promoted to an excited state upon absorption of light and undergo intersystem crossing (ISC) with oxygen to produce singlet oxygen. This species is highly cytotoxic, rapidly attacking any organic compounds it encounters. It is rapidly eliminated from cells, in an average of 3 µs.

Photochemical processes

When a photosensitiser is in its excited state (3Psen*) it can interact with molecular triplet oxygen (3O2) and produce radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS), crucial to the Type II mechanism. These species include singlet oxygen (1O2), hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide (O2−) ions. They can interact with cellular components including unsaturated lipids, amino acid residues and nucleic acids. If sufficient oxidative damage ensues, this will result in target-cell death (only within the illuminated area).

Photochemical mechanisms

When a chromophore molecule, such as a cyclic tetrapyrrolic molecule, absorbs a photon, one of its electrons is promoted into a higher-energy orbital, elevating the chromophore from the ground state (S0) into a short-lived, electronically excited state (Sn) composed of vibrational sub-levels (Sn′). The excited chromophore can lose energy by rapidly decaying through these sub-levels via internal conversion (IC) to populate the first excited singlet state (S1), before quickly relaxing back to the ground state.

The decay from the excited singlet state (S1) to the ground state (S0) is via fluorescence (S1 → S0). Singlet state lifetimes of excited fluorophores are very short (τfl. = 10−9–10−6 seconds) since transitions between the same spin states (S → S or T → T) conserve the spin multiplicity of the electron and, according to the Spin Selection Rules, are therefore considered "allowed" transitions. Alternatively, an excited singlet state electron (S1) can undergo spin inversion and populate the lower-energy first excited triplet state (T1) via intersystem crossing (ISC); a spin-forbidden process, since the spin of the electron is no longer conserved. The excited electron can then undergo a second spin-forbidden inversion and depopulate the excited triplet state (T1) by decaying to the ground state (S0) via phosphorescence (T1→ S0). Owing to the spin-forbidden triplet to singlet transition, the lifetime of phosphorescence (τP = 10−3 − 1 second) is considerably longer than that of fluorescence.

Photosensitisers and photochemistry

Tetrapyrrolic photosensitisers in the excited singlet state (1Psen*, S>0) are relatively efficient at intersystem crossing and can consequently have a high triplet-state quantum yield. The longer lifetime of this species is sufficient to allow the excited triplet state photosensitiser to interact with surrounding bio-molecules, including cell membrane constituents.

Photochemical reactions

Excited triplet-state photosensitisers can react via Type-I and Type-II processes. Type-I processes can involve the excited singlet or triplet photosensitiser (1Psen*, S1; 3Psen*, T1), however due to the short lifetime of the excited singlet state, the photosensitiser can only react if it is intimately associated with a substrate. In both cases the interaction is with readily oxidisable or reducible substrates. Type-II processes involve the direct interaction of the excited triplet photosensitiser (3Psen*, T1) with molecular oxygen (3O2, 3Σg).

Type-I processes

Type-I processes can be divided into Type I(i) and Type I(ii). Type I (i) involves the transfer of an electron (oxidation) from a substrate molecule to the excited state photosensitiser (Psen*), generating a photosensitiser radical anion (Psen•−) and a substrate radical cation (Subs•+). The majority of the radicals produced from Type-I(i) reactions react instantaneously with molecular oxygen (O2), generating a mixture of oxygen intermediates. For example, the photosensitiser radical anion can react instantaneously with molecular oxygen (3O2) to generate a superoxide radical anion (O2•−), which can go on to produce the highly reactive hydroxyl radical (OH•), initiating a cascade of cytotoxic free radicals; this process is common in the oxidative damage of fatty acids and other lipids.

The Type-I process (ii) involves the transfer of a hydrogen atom (reduction) to the excited state photosensitiser (Psen*). This generates free radicals capable of rapidly reacting with molecular oxygen and creating a complex mixture of reactive oxygen intermediates, including reactive peroxides.

Type-II processes

Type-II processes involve the direct interaction of the excited triplet state photosensitiser (3Psen*) with ground state molecular oxygen (3O2, 3Σg); a spin allowed transition—the excited state photosensitiser and ground state molecular oxygen are of the same spin state (T).

When the excited photosensitiser collides with molecular oxygen, a process of triplet-triplet annihilation takes place (3Psen* →1Psen and 3O2 →1O2). This inverts the spin of one oxygen molecule's (3O2) outermost antibonding electrons, generating two forms of singlet oxygen (1Δg and 1Σg), while simultaneously depopulating the photosensitiser's excited triplet state (T1 → S0). The higher-energy singlet oxygen state (1Σg, 157kJ mol−1 > 3Σg) is very short-lived (1Σg ≤ 0.33 milliseconds (methanol), undetectable in H2O/D2O) and rapidly relaxes to the lower-energy excited state (1Δg, 94kJ mol−1 > 3Σg). It is, therefore, this lower-energy form of singlet oxygen (1Δg) that is implicated in cell injury and cell death.

The highly-reactive singlet oxygen species (1O2) produced via the Type-II process act near to their site generation and within a radius of approximately 20 nm, with a typical lifetime of approximately 40 nanoseconds in biological systems.

It is possible that (over a 6 μs period) singlet oxygen can diffuse up to approximately 300 nm in vivo. Singlet oxygen can theoretically only interact with proximal molecules and structures within this radius. ROS initiate reactions with many biomolecules, including amino acid residues in proteins, such as tryptophan; unsaturated lipids like cholesterol and nucleic acid bases, particularly guanosine and guanine derivatives, with the latter base more susceptible to ROS. These interactions cause damage and potential destruction to cellular membranes and enzyme deactivation, culminating in cell death.

It is probable that in the presence of molecular oxygen and as a direct result of the photoirradiation of the photosensitiser molecule, both Type-I and II pathways play a pivotal role in disrupting cellular mechanisms and cellular structure. Nevertheless, considerable evidence suggests that the Type-II photo-oxygenation process predominates in the induction of cell damage, a consequence of the interaction between the irradiated photosensitiser and molecular oxygen. Cells in vivo may be partially protected against the effects of photodynamic therapy by the presence of singlet oxygen scavengers (such as histidine). Certain skin cells are somewhat resistant to PDT in the absence of molecular oxygen; further supporting the proposal that the Type-II process is at the heart of photoinitiated cell death.

The efficiency of Type-II processes is dependent upon the triplet state lifetime τT and the triplet quantum yield (ΦT) of the photosensitiser. Both of these parameters have been implicated in phototherapeutic effectiveness; further supporting the distinction between Type-I and Type-II mechanisms. However, the success of a photosensitiser is not exclusively dependent upon a Type-II process. Multiple photosensitisers display excited triplet lifetimes that are too short to permit a Type-II process to occur. For example, the copper metallated octaethylbenzochlorin photosensitiser has a triplet state lifetime of less than 20 nanoseconds and is still deemed to be an efficient photodynamic agent.

Photosensitizers

Many photosensitizers for PDT exist. They divide into porphyrins, chlorins and dyes. Examples include aminolevulinic acid (ALA), Silicon Phthalocyanine Pc 4, m-tetrahydroxyphenylchlorin (mTHPC) and mono-L-aspartyl chlorin e6 (NPe6).

Photosensitizers commercially available for clinical use include Allumera, Photofrin, Visudyne, Levulan, Foscan, Metvix, Hexvix, Cysview and Laserphyrin, with others in development, e.g. Antrin, Photochlor, Photosens, Photrex, Lumacan, Cevira, Visonac, BF-200 ALA, Amphinex and Azadipyrromethenes.

The major difference between photosensitizers is the parts of the cell that they target. Unlike in radiation therapy, where damage is done by targeting cell DNA, most photosensitizers target other cell structures. For example, mTHPC localizes in the nuclear envelope. In contrast, ALA localizes in the mitochondria and methylene blue in the lysosomes.

Cyclic tetrapyrrolic chromophores

Cyclic tetrapyrrolic molecules are fluorophores and photosensitisers. Cyclic tetrapyrrolic derivatives have an inherent similarity to the naturally occurring porphyrins present in living matter.

Porphyrins

Porphyrins are a group of naturally occurring and intensely coloured compounds, whose name is drawn from the Greek word porphura, or purple. These molecules perform biologically important roles, including oxygen transport and photosynthesis and have applications in fields ranging from fluorescent imaging to medicine. Porphyrins are tetrapyrrolic molecules, with the heart of the skeleton a heterocyclic macrocycle, known as a porphine. The fundamental porphine frame consists of four pyrrolic sub-units linked on opposing sides (α-positions, numbered 1, 4, 6, 9, 11, 14, 16 and 19) through four methine (CH) bridges (5, 10, 15 and 20), known as the meso-carbon atoms/positions. The resulting conjugated planar macrocycle may be substituted at the meso- and/or β-positions (2, 3, 7, 8, 12, 13, 17 and 18): if the meso- and β-hydrogens are substituted with non-hydrogen atoms or groups, the resulting compounds are known as porphyrins.

The inner two protons of a free-base porphyrin can be removed by strong bases such as alkoxides, forming a dianionic molecule; conversely, the inner two pyrrolenine nitrogens can be protonated with acids such as trifluoroacetic acid affording a dicationic intermediate. The tetradentate anionic species can readily form complexes with most metals.

Absorption spectroscopy

Porphyrin's highly conjugated skeleton produces a characteristic ultra-violet visible (UV-VIS) spectrum. The spectrum typically consists of an intense, narrow absorption band (ε > 200000 L⋅mol−1 cm−1) at around 400 nm, known as the Soret band or B band, followed by four longer wavelength (450–700 nm), weaker absorptions (ε > 20000 L⋅mol−1⋅cm−1 (free-base porphyrins)) referred to as the Q bands.

The Soret band arises from a strong electronic transition from the ground state to the second excited singlet state (S0 → S2); whereas the Q band is a result of a weak transition to the first excited singlet state (S0 → S1). The dissipation of energy via internal conversion (IC) is so rapid that fluorescence is only observed from depopulation of the first excited singlet state to the lower-energy ground state (S1 → S0).

Ideal photosensitisers

The key characteristic of a photosensitiser is the ability to preferentially accumulate in diseased tissue and induce a desired biological effect via the generation of cytotoxic species. Specific criteria:

- Strong absorption with a high extinction coefficient in the red/near infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum (600–850 nm)—allows deeper tissue penetration. (Tissue is much more transparent at longer wavelengths (~700–850 nm). Longer wavelengths allow the light to penetrate deeper and treat larger structures.)

- Suitable photophysical characteristics: a high-quantum yield of triplet formation (ΦT ≥ 0.5); a high singlet oxygen quantum yield (ΦΔ ≥ 0.5); a relatively long triplet state lifetime (τT, μs range); and a high triplet-state energy (≥ 94 kJ mol−1). Values of ΦT= 0.83 and ΦΔ = 0.65 (haematoporphyrin); ΦT = 0.83 and ΦΔ = 0.72 (etiopurpurin); and ΦT = 0.96 and ΦΔ = 0.82 (tin etiopurpurin) have been achieved

- Low dark toxicity and negligible cytotoxicity in the absence of light. (The photosensitizer should not be harmful to the target tissue until the treatment beam is applied.)

- Preferential accumulation in diseased/target tissue over healthy tissue

- Rapid clearance from the body post-procedure

- High chemical stability: single, well-characterised compounds, with a known and constant composition

- Short and high-yielding synthetic route (with easy translation into multi-gram scales/reactions)

- Simple and stable formulation

- Soluble in biological media, allowing intravenous administration. Otherwise, a hydrophilic delivery system must enable efficient and effective transportation of the photosensitiser to the target site via the bloodstream.

- Low photobleaching to prevent degradation of the photosensitizer so it can continue producing singlet oxygen

- Natural fluorescence (Many optical dosimetry techniques, such as fluorescence spectroscopy, depend on fluorescence.)

First generation

Disadvantages associated with first generation photosensitisers HpD and Photofrin (skin sensitivity and weak absorption at 630 nm) permitted some therapeutic use, but they markedly limited application to the wider field of disease. Second generation photosensitisers were key to the development of photodynamic therapy.

Second generation

5-Aminolaevulinic acid

5-Aminolaevulinic acid (ALA) is a prodrug used to treat and image multiple superficial cancers and tumours. ALA a key precursor in the biosynthesis of the naturally occurring porphyrin, haem.

Haem is synthesised in every energy-producing cell in the body and is a key structural component of haemoglobin, myoglobin and other haemproteins. The immediate precursor to haem is protoporphyrin IX (PPIX), an effective photosensitiser. Haem itself is not a photosensitiser, due to the coordination of a paramagnetic ion in the centre of the macrocycle, causing significant reduction in excited state lifetimes.

The haem molecule is synthesised from glycine and succinyl coenzyme A (succinyl CoA). The rate-limiting step in the biosynthesis pathway is controlled by a tight (negative) feedback mechanism in which the concentration of haem regulates the production of ALA. However, this controlled feedback can be by-passed by artificially adding excess exogenous ALA to cells. The cells respond by producing PPIX (photosensitiser) at a faster rate than the ferrochelatase enzyme can convert it to haem.

ALA, marketed as Levulan, has shown promise in photodynamic therapy (tumours) via both intravenous and oral administration, as well as through topical administration in the treatment of malignant and non-malignant dermatological conditions, including psoriasis, Bowen's disease and Hirsutism (Phase II/III clinical trials).

ALA accumulates more rapidly in comparison to other intravenously administered sensitisers. Typical peak tumour accumulation levels post-administration for PPIX are usually achieved within several hours; other (intravenous) photosensitisers may take up to 96 hours to reach peak levels. ALA is also excreted more rapidly from the body (∼24 hours) than other photosensitisers, minimising photosensitivity side effects.

Esterified ALA derivatives with improved bioavailability have been examined. A methyl ALA ester (Metvix) is now available for basal cell carcinoma and other skin lesions. Benzyl (Benvix) and hexyl ester (Hexvix) derivatives are used for gastrointestinal cancers and for the diagnosis of bladder cancer.

Verteporfin

Benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid ring A (BPD-MA) marketed as Visudyne (Verteporfin, for injection) has been approved by health authorities in multiple jurisdictions, including US FDA, for the treatment of wet AMD beginning in 1999. It has also undergone Phase III clinical trials (USA) for the treatment of cutaneous non-melanoma skin cancer.

The chromophore of BPD-MA has a red-shifted and intensified long-wavelength absorption maxima at approximately 690 nm. Tissue penetration by light at this wavelength is 50% greater than that achieved for Photofrin (λmax. = 630 nm).

Verteporfin has further advantages over the first generation sensitiser Photofrin. It is rapidly absorbed by the tumour (optimal tumour-normal tissue ratio 30–150 minutes post-intravenous injection) and is rapidly cleared from the body, minimising patient photosensitivity (1–2 days).

Purlytin

Chlorin photosensitiser tin etiopurpurin is marketed as Purlytin. Purlytin has undergone Phase II clinical trials for cutaneous metastatic breast cancer and Kaposi's sarcoma in patients with AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). Purlytin has been used successfully to treat the non-malignant conditions psoriasis and restenosis.

Chlorins are distinguished from the parent porphyrins by a reduced exocyclic double bond, decreasing the symmetry of the conjugated macrocycle. This leads to increased absorption in the long-wavelength portion of the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum (650–680 nm). Purlytin is a purpurin; a degradation product of chlorophyll.

Purlytin has a tin atom chelated in its central cavity that causes a red-shift of approximately 20–30 nm (with respect to Photofrin and non-metallated etiopurpurin, λmax.SnEt2 = 650 nm). Purlytin has been reported to localise in skin and produce a photoreaction 7–14 days post-administration.

Foscan

Tetra(m-hydroxyphenyl)chlorin (mTHPC) is in clinical trials for head and neck cancers under the trade name Foscan. It has also been investigated in clinical trials for gastric and pancreatic cancers, hyperplasia, field sterilisation after cancer surgery and for the control of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Foscan has a singlet oxygen quantum yield comparable to other chlorin photosensitisers but lower drug and light doses (approximately 100 times more photoactive than Photofrin).

Foscan can render patients photosensitive for up to 20 days after initial illumination.

Lutex

Lutetium texaphyrin, marketed under the trade name Lutex and Lutrin, is a large porphyrin-like molecule. Texaphyrins are expanded porphyrins that have a penta-aza core. It offers strong absorption in the 730–770 nm region. Tissue transparency is optimal in this range. As a result, Lutex-based PDT can (potentially) be carried out more effectively at greater depths and on larger tumours.

Lutex has entered Phase II clinical trials for evaluation against breast cancer and malignant melanomas.

A Lutex derivative, Antrin, has undergone Phase I clinical trials for the prevention of restenosis of vessels after cardiac angioplasty by photoinactivating foam cells that accumulate within arteriolar plaques. A second Lutex derivative, Optrin, is in Phase I trials for AMD.

Texaphyrins also have potential as radiosensitisers (Xcytrin) and chemosensitisers. Xcytrin, a gadolinium texaphyrin (motexafin gadolinium), has been evaluated in Phase III clinical trials against brain metastases and Phase I clinical trials for primary brain tumours.

ATMPn

9-Acetoxy-2,7,12,17-tetrakis-(β-methoxyethyl)-porphycene has been evaluated as an agent for dermatological applications against psoriasis vulgaris and superficial non-melanoma skin cancer.

Zinc phthalocyanine

A liposomal formulation of zinc phthalocyanine (CGP55847) has undergone clinical trials (Phase I/II, Switzerland) against squamous cell carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract. Phthalocyanines (PCs) are related to tetra-aza porphyrins. Instead of four bridging carbon atoms at the meso-positions, as for the porphyrins, PCs have four nitrogen atoms linking the pyrrolic sub-units. PCs also have an extended conjugate pathway: a benzene ring is fused to the β-positions of each of the four-pyrrolic sub-units. These rings strengthen the absorption of the chromophore at longer wavelengths (with respect to porphyrins). The absorption band of PCs is almost two orders of magnitude stronger than the highest Q band of haematoporphyrin. These favourable characteristics, along with the ability to selectively functionalise their peripheral structure, make PCs favourable photosensitiser candidates.

A sulphonated aluminium PC derivative (Photosense) has entered clinical trials (Russia) against skin, breast and lung malignancies and cancer of the gastrointestinal tract. Sulphonation significantly increases PC solubility in polar solvents including water, circumventing the need for alternative delivery vehicles.

PC4 is a silicon complex under investigation for the sterilisation of blood components against human colon, breast and ovarian cancers and against glioma.

A shortcoming of many of the metallo-PCs is their tendency to aggregate in aqueous buffer (pH 7.4), resulting in a decrease, or total loss, of their photochemical activity. This behaviour can be minimised in the presence of detergents.

Metallated cationic porphyrazines (PZ), including PdPZ+, CuPZ+, CdPZ+, MgPZ+, AlPZ+ and GaPZ+, have been tested in vitro on V-79 (Chinese hamster lung fibroblast) cells. These photosensitisers display substantial dark toxicity.

Naphthalocyanines

Naphthalocyanines (NCs) are an extended PC derivative. They have an additional benzene ring attached to each isoindole sub-unit on the periphery of the PC structure. Subsequently, NCs absorb strongly at even longer wavelengths (approximately 740–780 nm) than PCs (670–780 nm). This absorption in the near infrared region makes NCs candidates for highly pigmented tumours, including melanomas, which present significant absorption problems for visible light.

However, problems associated with NC photosensitisers include lower stability, as they decompose in the presence of light and oxygen. Metallo-NCs, which lack axial ligands, have a tendency to form H-aggregates in solution. These aggregates are photoinactive, thus compromising the photodynamic efficacy of NCs.

Silicon naphthalocyanine attached to copolymer PEG-PCL (poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(ε-caprolactone)) accumulates selectively in cancer cells and reaches a maximum concentration after about one day. The compound provides real time near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence imaging with an extinction coefficient of 2.8 × 105 M−1 cm−1 and combinatorial phototherapy with dual photothermal and photodynamic therapeutic mechanisms that may be appropriate for adriamycin-resistant tumors. The particles had a hydrodynamic size of 37.66 ± 0.26 nm (polydispersity index = 0.06) and surface charge of −2.76 ± 1.83 mV.

Functional groups

Altering the peripheral functionality of porphyrin-type chromophores can affect photodynamic activity.

Diamino platinum porphyrins show high anti-tumour activity, demonstrating the combined effect of the cytotoxicity of the platinum complex and the photodynamic activity of the porphyrin species.

Positively charged PC derivatives have been investigated. Cationic species are believed to selectively localise in the mitochondria.

Zinc and copper cationic derivatives have been investigated. The positively charged zinc complexed PC is less photodynamically active than its neutral counterpart in vitro against V-79 cells.

Water-soluble cationic porphyrins bearing nitrophenyl, aminophenyl, hydroxyphenyl and/or pyridiniumyl functional groups exhibit varying cytotoxicity to cancer cells in vitro, depending on the nature of the metal ion (Mn, Fe, Zn, Ni) and on the number and type of functional groups. The manganese pyridiniumyl derivative has shown the highest photodynamic activity, while the nickel analogue is photoinactive.

Another metallo-porphyrin complex, the iron chelate, is more photoactive (towards HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus in MT-4 cells) than the manganese complexes; the zinc derivative is photoinactive.

The hydrophilic sulphonated porphyrins and PCs (AlPorphyrin and AlPC) compounds were tested for photodynamic activity. The disulphonated analogues (with adjacent substituted sulphonated groups) exhibited greater photodynamic activity than their di-(symmetrical), mono-, tri- and tetra-sulphonated counterparts; tumour activity increased with increasing degree of sulphonation.

Third generation

Many photosensitisers are poorly soluble in aqueous media, particularly at physiological pH, limiting their use.

Alternate delivery strategies range from the use of oil-in-water (o/w) emulsions to carrier vehicles such as liposomes and nanoparticles. Although these systems may increase therapeutic effects, the carrier system may inadvertently decrease the "observed" singlet oxygen quantum yield (ΦΔ): the singlet oxygen generated by the photosensitiser must diffuse out of the carrier system; and since singlet oxygen is believed to have a narrow radius of action, it may not reach the target cells. The carrier may limit light absorption, reducing singlet oxygen yield.

Another alternative that does not display the scattering problem is the use of moieties. Strategies include directly attaching photosensitisers to biologically active molecules such as antibodies.

Metallation

Various metals form into complexes with photosensitiser macrocycles. Multiple second generation photosensitisers contain a chelated central metal ion. The main candidates are transition metals, although photosensitisers co-ordinated to group 13 (Al, AlPcS4) and group 14 (Si, SiNC and Sn, SnEt2) metals have been synthesised.

The metal ion does not confer definite photoactivity on the complex. Copper (II), cobalt (II), iron (II) and zinc (II) complexes of Hp are all photoinactive in contrast to metal-free porphyrins. However, texaphyrin and PC photosensitisers do not contain metals; only the metallo-complexes have demonstrated efficient photosensitisation.

The central metal ion, bound by a number of photosensitisers, strongly influences the photophysical properties of the photosensitiser. Chelation of paramagnetic metals to a PC chromophore appears to shorten triplet lifetimes (down to nanosecond range), generating variations in the triplet quantum yield and triplet lifetime of the photoexcited triplet state.

Certain heavy metals are known to enhance inter-system crossing (ISC). Generally, diamagnetic metals promote ISC and have a long triplet lifetime. In contrast, paramagnetic species deactivate excited states, reducing the excited-state lifetime and preventing photochemical reactions. However, exceptions to this generalisation include copper octaethylbenzochlorin.

Many metallated paramagnetic texaphyrin species exhibit triplet-state lifetimes in the nanosecond range. These results are mirrored by metallated PCs. PCs metallated with diamagnetic ions, such as Zn2+, Al3+ and Ga3+, generally yield photosensitisers with desirable quantum yields and lifetimes (ΦT 0.56, 0.50 and 0.34 and τT 187, 126 and 35 μs, respectively). Photosensitiser ZnPcS4 has a singlet oxygen quantum yield of 0.70; nearly twice that of most other mPCs (ΦΔ at least 0.40).

Expanded metallo-porphyrins

Expanded porphyrins have a larger central binding cavity, increasing the range of potential metals.

Diamagnetic metallo-texaphyrins have shown photophysical properties; high triplet quantum yields and efficient generation of singlet oxygen. In particular, the zinc and cadmium derivatives display triplet quantum yields close to unity. In contrast, the paramagnetic metallo-texaphyrins, Mn-Tex, Sm-Tex and Eu-Tex, have undetectable triplet quantum yields. This behaviour is parallel with that observed for the corresponding metallo-porphyrins.

The cadmium-texaphyrin derivative has shown in vitro photodynamic activity against human leukemia cells and Gram positive (Staphylococcus) and Gram negative (Escherichia coli) bacteria. Although follow-up studies have been limited with this photosensitiser due to the toxicity of the complexed cadmium ion.

A zinc-metallated seco-porphyrazine has a high quantum singlet oxygen yield (ΦΔ 0.74). This expanded porphyrin-like photosensitiser has shown the best singlet oxygen photosensitising ability of any of the reported seco-porphyrazines. Platinum and palladium derivatives have been synthesised with singlet oxygen quantum yields of 0.59 and 0.54, respectively.

Metallochlorins/bacteriochlorins

The tin (IV) purpurins are more active when compared with analogous zinc (II) purpurins, against human cancers.

Sulphonated benzochlorin derivatives demonstrated a reduced phototherapeutic response against murine leukemia L1210 cells in vitro and transplanted urothelial cell carcinoma in rats, whereas the tin (IV) metallated benzochlorins exhibited an increased photodynamic effect in the same tumour model.

Copper octaethylbenzochlorin demonstrated greater photoactivity towards leukemia cells in vitro and a rat bladder tumour model. It may derive from interactions between the cationic iminium group and biomolecules. Such interactions may allow electron-transfer reactions to take place via the short-lived excited singlet state and lead to the formation of radicals and radical ions. The copper-free derivative exhibited a tumour response with short intervals between drug administration and photodynamic activity. Increased in vivo activity was observed with the zinc benzochlorin analogue.

Metallo-phthalocyanines

PCs properties are strongly influenced by the central metal ion. Co-ordination of transition metal ions gives metallo-complexes with short triplet lifetimes (nanosecond range), resulting in different triplet quantum yields and lifetimes (with respect to the non-metallated analogues). Diamagnetic metals such as zinc, aluminium and gallium, generate metallo-phthalocyanines (MPC) with high triplet quantum yields (ΦT ≥ 0.4) and short lifetimes (ZnPCS4 τT = 490 Fs and AlPcS4 τT = 400 Fs) and high singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ ≥ 0.7). As a result, ZnPc and AlPc have been evaluated as second generation photosensitisers active against certain tumours.

Metallo-naphthocyaninesulfobenzo-porphyrazines (M-NSBP)

Aluminium (Al3+) has been successfully coordinated to M-NSBP. The resulting complex showed photodynamic activity against EMT-6 tumour-bearing Balb/c mice (disulphonated analogue demonstrated greater photoactivity than the mono-derivative).

Metallo-naphthalocyanines

Work with zinc NC with various amido substituents revealed that the best phototherapeutic response (Lewis lung carcinoma in mice) with a tetrabenzamido analogue. Complexes of silicon (IV) NCs with two axial ligands in anticipation the ligands minimise aggregation. Disubstituted analogues as potential photodynamic agents (a siloxane NC substituted with two methoxyethyleneglycol ligands) are an efficient photosensitiser against Lewis lung carcinoma in mice. SiNC[OSi(i-Bu)2-n-C18H37]2 is effective against Balb/c mice MS-2 fibrosarcoma cells. Siloxane NCs may be efficacious photosensitisers against EMT-6 tumours in Balb/c mice. The ability of metallo-NC derivatives (AlNc) to generate singlet oxygen is weaker than the analogous (sulphonated) metallo-PCs (AlPC); reportedly 1.6–3 orders of magnitude less.

In porphyrin systems, the zinc ion (Zn2+) appears to hinder the photodynamic activity of the compound. By contrast, in the higher/expanded π-systems, zinc-chelated dyes form complexes with good to high results.

An extensive study of metallated texaphyrins focused on the lanthanide (III) metal ions, Y, In, Lu, Cd, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm and Yb found that when diamagnetic Lu (III) was complexed to texaphyrin, an effective photosensitiser (Lutex) was generated. However, using the paramagnetic Gd (III) ion for the Lu metal, exhibited no photodynamic activity. The study found a correlation between the excited-singlet and triplet state lifetimes and the rate of ISC of the diamagnetic texaphyrin complexes, Y(III), In (III) and Lu (III) and the atomic number of the cation.

Paramagnetic metallo-texaphyrins displayed rapid ISC. Triplet lifetimes were strongly affected by the choice of metal ion. The diamagnetic ions (Y, In and Lu) displayed triplet lifetimes ranging from 187, 126 and 35 μs, respectively. Comparable lifetimes for the paramagnetic species (Eu-Tex 6.98 μs, Gd-Tex 1.11, Tb-Tex < 0.2, Dy-Tex 0.44 × 10−3, Ho-Tex 0.85 × 10−3, Er-Tex 0.76 × 10−3, Tm-Tex 0.12 × 10−3 and Yb-Tex 0.46) were obtained.

Three measured paramagnetic complexes measured significantly lower than the diamagnetic metallo-texaphyrins.

In general, singlet oxygen quantum yields closely followed the triplet quantum yields.

Various diamagnetic and paramagnetic texaphyrins investigated have independent photophysical behaviour with respect to a complex's magnetism. The diamagnetic complexes were characterised by relatively high fluorescence quantum yields, excited-singlet and triplet lifetimes and singlet oxygen quantum yields; in distinct contrast to the paramagnetic species.

The +2 charged diamagnetic species appeared to exhibit a direct relationship between their fluorescence quantum yields, excited state lifetimes, rate of ISC and the atomic number of the metal ion. The greatest diamagnetic ISC rate was observed for Lu-Tex; a result ascribed to the heavy atom effect. The heavy atom effect also held for the Y-Tex, In-Tex and Lu-Tex triplet quantum yields and lifetimes. The triplet quantum yields and lifetimes both decreased with increasing atomic number. The singlet oxygen quantum yield correlated with this observation.

Photophysical properties displayed by paramagnetic species were more complex. The observed data/behaviour was not correlated with the number of unpaired electrons located on the metal ion. For example:

- ISC rates and the fluorescence lifetimes gradually decreased with increasing atomic number.

- Gd-Tex and Tb-Tex chromophores showed (despite more unpaired electrons) slower rates of ISC and longer lifetimes than Ho-Tex or Dy-Tex.

To achieve selective target cell destruction, while protecting normal tissues, either the photosensitizer can be applied locally to the target area, or targets can be locally illuminated. Skin conditions, including acne, psoriasis and also skin cancers, can be treated topically and locally illuminated. For internal tissues and cancers, intravenously administered photosensitizers can be illuminated using endoscopes and fiber optic catheters.

Photosensitizers can target viral and microbial species, including HIV and MRSA.[16] Using PDT, pathogens present in samples of blood and bone marrow can be decontaminated before the samples are used further for transfusions or transplants. PDT can also eradicate a wide variety of pathogens of the skin and of the oral cavities. Given the seriousness that drug resistant pathogens have now become, there is increasing research into PDT as a new antimicrobial therapy.

Applications

Acne

PDT is currently in clinical trials as a treatment for severe acne. Initial results have shown for it to be effective as a treatment only for severe acne. A systematic review conducted in 2016 found that PDT is a "safe and effective method of treatment" for acne. The treatment may cause severe redness and moderate to severe pain and burning sensation in some people. (see also: Levulan) One phase II trial, while it showed improvement, was not superior to blue/violet light alone.

Cancer

In February 2019, medical scientists announced that iridium attached to albumin, creating a photosensitized molecule, can penetrate cancer cells and, after being irradiated with light, destroy the cancer cells.

Ophthalmology

As cited above, verteporfin was widely approved for the treatment of wet AMD beginning in 1999. The drug targets the neovasculature that is caused by the condition.

Photoimmunotherapy

Photoimmunotherapy is an oncological treatment for various cancers that combines photodynamic therapy of tumor with immunotherapy treatment. Combining photodynamic therapy with immunotherapy enhances the immunostimulating response and has synergistic effects for metastatic cancer treatment.

Vascular targeting

Some photosensitisers naturally accumulate in the endothelial cells of vascular tissue allowing 'vascular targeted' PDT.

Verteporfin was shown to target the neovasculature resulting from macular degeneration in the macula within the first thirty minutes after intravenous administration of the drug.

Compared to normal tissues, most types of cancers are especially active in both the uptake and accumulation of photosensitizers agents, which makes cancers especially vulnerable to PDT. Since photosensitizers can also have a high affinity for vascular endothelial cells.

Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy

Some photosensitizers have been chemically modified to incorporate into the mycomembrane of mycobacteria. These molecules show promising in vitro activity and are potential candidates for targeted delivery of photosensitizers. Furthermore, antibacterial photodynamic therapy has the potential to kill multidrug-resistant pathogenic bacteria very effectively and is recognized for its low potential to induce drug resistance in bacteria, which can be rapidly developed against traditional antibiotic therapy.

History

Modern era

In the late nineteenth century. Finsen successfully demonstrated phototherapy by employing heat-filtered light from a carbon-arc lamp (the "Finsen lamp") in the treatment of a tubercular condition of the skin known as lupus vulgaris, for which he won the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

In 1913 another German scientist, Meyer-Betz, described the major stumbling block of photodynamic therapy. After injecting himself with haematoporphyrin (Hp, a photosensitiser), he swiftly experienced a general skin sensitivity upon exposure to sunlight—a recurrent problem with many photosensitisers.

The first evidence that agents, photosensitive synthetic dyes, in combination with a light source and oxygen could have potential therapeutic effect was made at the turn of the 20th century in the laboratory of Hermann von Tappeiner in Munich, Germany. Germany was leading the world in industrial dye synthesis at the time.

While studying the effects of acridine on paramecia cultures, Oscar Raab, a student of von Tappeiner observed a toxic effect. Fortuitously Raab also observed that light was required to kill the paramecia. Subsequent work in von Tappeiner's laboratory showed that oxygen was essential for the 'photodynamic action' – a term coined by von Tappeiner.

Von Tappeiner and colleagues performed the first PDT trial in patients with skin carcinoma using the photosensitizer, eosin. Of 6 patients with a facial basal cell carcinoma, treated with a 1% eosin solution and long-term exposure either to sunlight or arc-lamp light, 4 patients showed total tumour resolution and a relapse-free period of 12 months.

In 1924 Policard revealed the diagnostic capabilities of hematoporphyrin fluorescence when he observed that ultraviolet radiation excited red fluorescence in the sarcomas of laboratory rats. Policard hypothesized that the fluorescence was associated with endogenous hematoporphyrin accumulation.

In 1948 Figge and co-workers showed on laboratory animals that porphyrins exhibit a preferential affinity to rapidly dividing cells, including malignant, embryonic and regenerative cells. They proposed that porphyrins could be used to treat cancer.

Photosensitizer Haematoporphyrin Derivative (HpD), was first characterised in 1960 by Lipson. Lipson sought a diagnostic agent suitable for tumor detection. HpD allowed Lipson to pioneer the use of endoscopes and HpD fluorescence. HpD is a porphyrin species derived from haematoporphyrin, Porphyrins have long been considered as suitable agents for tumour photodiagnosis and tumour PDT because cancerous cells exhibit significantly greater uptake and affinity for porphyrins compared to normal tissues. This had been observed by other researchers prior to Lipson.

Thomas Dougherty and co-workers at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, New York, clinically tested PDT in 1978. They treated 113 cutaneous or subcutaneous malignant tumors with HpD and observed total or partial resolution of 111 tumors. Dougherty helped expand clinical trials and formed the International Photodynamic Association, in 1986.

John Toth, product manager for Cooper Medical Devices Corp/Cooper Lasersonics, noticed the "photodynamic chemical effect" of the therapy and wrote the first white paper naming the therapy "Photodynamic Therapy" (PDT) with early clinical argon dye lasers circa 1981. The company set up 10 clinical sites in Japan where the term "radiation" had negative connotations.

HpD, under the brand name Photofrin, was the first PDT agent approved for clinical use in 1993 to treat a form of bladder cancer in Canada. Over the next decade, both PDT and the use of HpD received international attention and greater clinical acceptance and led to the first PDT treatments approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration Japa and parts of Europe for use against certain cancers of the oesophagus and non-small cell lung cancer.

Photofrin had the disadvantages of prolonged patient photosensitivity and a weak long-wavelength absorption (630 nm). This led to the development of second generation photosensitisers, including Verteporfin (a benzoporphyrin derivative, also known as Visudyne) and more recently, third generation targetable photosensitisers, such as antibody-directed photosensitisers.

In the 1980s, David Dolphin, Julia Levy and colleagues developed a novel photosensitizer, verteporfin. Verteporfin, a porphyrin derivative, is activated at 690 nm, a much longer wavelength than Photofrin. It has the property of preferential uptake by neovasculature. It has been widely tested for its use in treating skin cancers and received FDA approval in 2000 for the treatment of wet age related macular degeneration. As such it was the first medical treatment ever approved for this condition, which is a major cause of vision loss.

Russian scientists pioneered a photosensitizer called Photogem which, like HpD, was derived from haematoporphyrin in 1990 by Mironov and coworkers. Photogem was approved by the Ministry of Health of Russia and tested clinically from February 1992 to 1996. A pronounced therapeutic effect was observed in 91 percent of the 1500 patients. 62 percent had total tumor resolution. A further 29 percent had >50% tumor shrinkage. In early diagnosis patients 92 percent experienced complete resolution.

Russian scientists collaborated with NASA scientists who were looking at the use of LEDs as more suitable light sources, compared to lasers, for PDT applications.

Since 1990, the Chinese have been developing clinical expertise with PDT, using domestically produced photosensitizers, derived from Haematoporphyrin. China is notable for its expertise in resolving difficult to reach tumours.

Photodynamic and photobiology organizations

- International Photodynamic Association (IPA)

- American Society for Photobiology (ASP)

- PanAmerican PDT Association Archived 2017-12-30 at the Wayback Machine

- European Society for Photobiology (ESP)

Miscellany

PUVA therapy uses psoralen as photosensitiser and UVA ultraviolet as light source, but this form of therapy is usually classified as a separate form of therapy from photodynamic therapy.

To allow treatment of deeper tumours some researchers are using internal chemiluminescence to activate the photosensitiser.