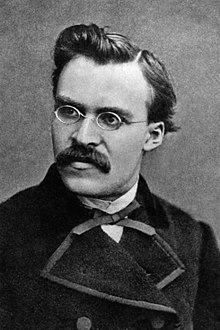

Friedrich Nietzsche's influence and reception varied widely and may be roughly divided into various chronological periods. Reactions were anything but uniform, and proponents of various ideologies attempted to appropriate his work quite early.

Overview

Beginning while Nietzsche was still alive, though incapacitated by mental illness, many Germans discovered his appeals for greater heroic individualism and personality development in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, but responded to those appeals in diverging ways. He had some following among left-wing Germans in the 1890s. Nietzsche's anarchistic influence was particularly strong in France and the United States.

By World War I, German soldiers even received copies of Thus Spoke Zarathustra as gifts. The Dreyfus affair provides another example of his reception: the French antisemitic Right labelled the Jewish and leftist intellectuals who defended Alfred Dreyfus as "Nietzscheans". Such seemingly paradoxical acceptance by diametrically opposed camps is typical of the history of the reception of Nietzsche's thought. In the context of the rise of French fascism, one researcher notes, "Although, as much recent work has stressed, Nietzsche had an important impact on "leftist" French ideology and theory, this should not obscure the fact that his work was also crucial to the right and to the neither right nor left fusions of developing French fascism.

Indeed, as Ernst Nolte proposed, Maurrassian ideology of "aristocratic revolt against egalitarian-utopian 'transcendence'" (transcendence being Nolte's term for the ontological absence of theodic center justifying modern "emancipation culture") and the interrelation between Nietzschean ideology and proto-fascism offer extensive space for criticism and the Nietzschean ambiance pervading French ideological fermentation of extremism in time birthing formal fascism, is unavoidable.

Many political leaders of the 20th century were at least superficially familiar with Nietzsche's ideas. However, it is not always possible to determine whether or not they actually read his work. Regarding Hitler, for example, there is a debate. Some authors claim that he probably never read Nietzsche, or that if he did, his reading was not extensive. Hitler more than likely became familiar with Nietzsche quotes during his time in Vienna when quotes by Nietzsche were frequently published in pan-German newspapers. Nevertheless, others point to a quote in Hitler's Table Talk, where the dictator mentioned Nietzsche when he spoke about what he called "great men", as an indication that Hitler may have been familiarized with Nietzsche's work. Other authors like Melendez (2001) point out to the parallels between Hitler's and Nietzsche's titanic anti-egalitarianism, and the idea of the "übermensch", a term which was frequently used by Hitler and Mussolini to refer to the so-called "Aryan race", or rather, its projected future after fascist engineering. Alfred Rosenberg, an influential Nazi ideologist, also delivered a speech in which he related National Socialism to Nietzsche's ideology. Broadly speaking, despite Nietzsche's hostility towards anti-semitism and nationalism, the Nazis made very selective use of Nietzsche's philosophy, and eventually, this association caused Nietzsche's reputation to suffer following World War II.

On the other hand, it is known that Mussolini early on heard lectures about Nietzsche, Vilfredo Pareto, and others in ideologically forming fascism. A girlfriend of Mussolini, Margherita Sarfatti, who was Jewish, relates that Nietzsche virtually was the transforming factor in Mussolini's "conversion" from hard socialism to spiritualistic, ascetic fascism,: "In 1908 he presented his conception of the superman's role in modern society in a writing on Nietzsche entitled, "The Philosophy of Force."

Nietzsche's influence on Continental philosophy increased dramatically after the Second World War.

Nietzsche and anarchism

During the 19th century, Nietzsche was frequently associated with anarchist movements, in spite of the fact that in his writings he definitely holds a negative view of egalitarian anarchists. Nevertheless, Nietzsche's ideas generated strong interest from key figures from the historical anarchist movement which began in the 1890s. According to a recent study, "Gustav Landauer, Emma Goldman and others reflected on the chances offered and the dangers posed by these ideas in relation to their own politics. Heated debates over meaning, for example on the will to power or on the status of women in Nietzsche’s works, provided even the most vehement critics such as Peter Kropotkin with productive cues for developing their own theories. In recent times, a newer strand called post-anarchism has invoked Nietzsche’s ideas, while also disregarding the historical variants of Nietzschean anarchism. This calls into question the innovative potential of post-anarchism."

Some hypothesize on certain grounds Nietzsche's violent stance against anarchism may (at least partially) be the result of a popular association during this period between his ideas and those of Max Stirner. Thus far, no plagiarism has been detected at all, but a probable concealed influence in his formative years.

Spencer Sunshine writes, "There were many things that drew anarchists to Nietzsche: his hatred of the state; his disgust for the mindless social behavior of "herds"; his anti-Christianity; his distrust of the effect of both the market and the state on cultural production; his desire for an "overman" — that is, for a new human who was to be neither master nor slave; his praise of the ecstatic and creative self, with the artist as his prototype, who could say, "Yes" to the self-creation of a new world on the basis of nothing; and his forwarding of the "transvaluation of values" as source of change, as opposed to a Marxist conception of class struggle and the dialectic of a linear history." Lacking in Nietzsche is the anarchist utopian-egalitarian belief that every soul is capable of epic greatness: Nietzsche's aristocratic elitism is the death-knell of any Nietzschean conventional anarchism.

According to Sunshine: "The list is not limited to culturally oriented anarchists such as Emma Goldman, who gave dozens of lectures about Nietzsche and baptized him as an honorary anarchist. Pro-Nietzschean anarchists also include prominent Spanish CNT–FAI members in the 1930s such as Salvador Seguí and anarcha-feminist Federica Montseny; anarcho-syndicalist militants like Rudolf Rocker; and even the younger Murray Bookchin, who cited Nietzsche's conception of the 'transvaluation of values' in support of the Spanish anarchist project." Also in European individualist anarchist circles his influence is clear in thinker/activists such as Émile Armand and Renzo Novatore among others. Also more recently in post-left anarchy, Nietzsche is present in the thought of Hakim Bey and Wolfi Landstreicher.

Nietzsche and fascism

The Italian and German fascist regimes were eager to lay claim to Nietzsche's ideas, and to position themselves as inspired by them. In 1932, Nietzsche's sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, received a bouquet of roses from Adolf Hitler during a German premiere of Benito Mussolini's 100 Days, and in 1934 Hitler personally presented her with a wreath for Nietzsche's grave carrying the words "To A Great Fighter". Also in 1934, Elisabeth gave to Hitler Nietzsche's favorite walking stick, and Hitler was photographed gazing into the eyes of a white marble bust of Nietzsche. Heinrich Hoffmann's popular biography Hitler as Nobody Knows Him (which sold nearly a half-million copies by 1938) featured this photo with the caption reading: "The Führer before the bust of the German philosopher whose ideas have fertilized two great popular movements: the national socialist of Germany and the fascist of Italy."

Nietzsche was no less popular among French fascists, perhaps with more doctrinal truthfulness, as Robert S. Wistrich has pointed out

The "fascist" Nietzsche was above all considered to be a heroic opponent of necrotic Enlightenment "rationality" and a kind of spiritual vitalist, who had glorified war and violence in an age of herd-lemming shopkeepers, inspiring the anti-Marxist revolutions of the interwar period. According to the French fascist Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, it was the Nietzschean emphasis on the autotelic power of the Will that inspired the mystic voluntarism and political activism of his comrades. Such politicized readings were vehemently rejected by another French writer, the socialo-communist anarchist Georges Bataille, who in the 1930s sought to establish (in ambiguous success) the "radical incompatibility" between Nietzsche (as a thinker who abhorred mass politics) and "the fascist reactionaries." He argued that nothing was more alien to Nietzsche than the pan-Germanism, racism, militarism and anti-Semitism of the Nazis, into whose service the German philosopher had been pressed. Bataille here was sharp-witted but combined half-truths without his customary dialectical finesse.

The German philosopher Martin Heidegger, an active member of the Nazi Party, noted that everyone in his day was either 'for' or 'against' Nietzsche while claiming that this thinker heard a "command to reflect on the essence of a planetary domination." Alan D. Schrift cites this passage and writes, "That Heidegger sees Nietzsche heeding a command to reflect and prepare for earthly domination is of less interest to me than his noting that everyone thinks in terms of a position for or against Nietzsche. In particular, the gesture of setting up 'Nietzsche' as a battlefield on which to take one's stand against or to enter into competition with the ideas of one's intellectual predecessors or rivals has happened quite frequently in the twentieth century."

Marching in ideological warfare against the arrows from Bataille, Thomas Mann, Albert Camus and others, claimed that the Nazi movement, despite Nietzsche' virulent hatred of both volkist-populist socialist and nationalism ("national socialism"), did, in certain of its emphases, share an affinity with Nietzsche's ideas, including his ferocious attacks against democracy, egalitarianism, the communistic-socialistic social model, popular Christianity, parliamentary government, and a number of other things. In The Will to Power Nietzsche praised – sometimes metaphorically, other times both metaphorically and literally – the sublimity of war and warriors, and heralded an international ruling race that would become the "lords of the earth". Here Nietzsche was referring to pan-Europeanism of a Caesarist type, positively embracing Jews, not a Germanic master race but a neo-imperial elite of culturally refined "redeemers" of humanity, which was otherwise considered wretched and plebeian and ugly in its mindless existence.

The Nazis appropriated, or rather received also inspiration in this case, from Nietzsche's extremely old-fashioned and semi-feudal views on women: Nietzsche despised modern feminism, along with democracy and socialism, as mere egalitarian leveling movements of nihilism. He forthrightly declared, "Man shall be trained for war and woman for the procreation of the warrior, anything else is folly"; and was indeed unified with the Nazi world-view at least in terms of the social role of women: "They belong in the kitchen and their chief role in life is to beget children for German warriors." Here is one area where Nietzsche indeed did not contradict the Nazis in his politics of "aristocratic radicalism."

During the interbellum years, certain Nazis had employed a highly selective reading of Nietzsche's work to advance their ideology, notably Alfred Baeumler, who strikingly omitted the fact of Nietzsche's anti-socialism and anti-nationalism (for Nietzsche, both equally contemptible mass herd movements of modernity) in his reading of The Will to Power. The era of Nazi rule (1933–1945) saw Nietzsche's writings widely studied in German (and, after 1938, Austrian) schools and universities. Despite the fact that Nietzsche had expressed his disgust with plebeian-volkist antisemitism and supremacist German nationalism in the most forthright terms possible (e.g. he resolved "to have nothing to do with anyone involved in the perfidious race-fraud"), phrases like "the will to power" became common in Nazi circles. The wide popularity of Nietzsche among Nazis stemmed in part from the endeavors of his sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, the editor of Nietzsche's work after his 1889 breakdown, and an eventual Nazi sympathizer. Mazzino Montinari, while editing Nietzsche's posthumous works in the 1960s, found that Förster-Nietzsche, while editing the posthumous fragments making up The Will to Power, had cut extracts, changed their order, quoted him out of context, etc.

Nietzsche's reception among the more intellectually percipient or zealous fascists was not universally warm. For example, one "rabidly Nazi writer, Curt von Westernhagen, who announced in his book Nietzsche, Juden, Antijuden (1936) that the time had come to expose the 'defective personality of Nietzsche whose inordinate tributes for, and espousal of, Jews had caused him to depart from the Germanic principles enunciated by Meister Richard Wagner'."

The real problem with the labelling of Nietzsche as a fascist, or worse, a Nazi, is that it ignores the fact that Nietzsche's aristocratism seeks to revive an older conception of politics, one which he locates in Greek agon which [...] has striking affinities with the philosophy of action expounded in our own time by Hannah Arendt. Once an affinity like this is appreciated, the absurdity of describing Nietzsche's political thought as 'fascist', or Nazi, becomes readily apparent.

Nietzsche and Zionism

Jacob Golomb observed, "Nietzsche's ideas were widely disseminated among and appropriated by the first Hebrew Zionist writers and leaders." According to Steven Aschheim, "Classical Zionism, that essentially secular and modernizing movement, was acutely aware of the crisis of Jewish tradition and its supporting institutions. Nietzsche was enlisted as an authority for articulating the movement's ruptured relationship with the past and a force in its drive to normalization and its activist ideal of self-creating Hebraic New Man."

Francis R. Nicosia notes, "At the height of his fame between 1895 and 1902, some of Nietzsche's ideas seemed to have a particular resonance for some Zionists, including Theodor Herzl." Under his editorship the Neue Freie Presse dedicated seven consecutive issues to Nietzsche obituaries, and Golomb notes that Herzl's cousin Raoul Auernheimer claimed Herzl was familiar with Nietzsche and had "absorbed his style."

However, Gabriel Sheffer suggests that Herzl was too bourgeois and too eager to be accepted into mainstream society to be much of a revolutionary (even an "aristocratic" one), and hence could not have been strongly influenced by Nietzsche, but remarks, "Some East European Jewish intellectuals, such as the writers Yosef Hayyim Brenner and Micha Josef Berdyczewski, followed after Herzl because they thought that Zionism offered the chance for a Nietzschean 'transvaluation of values' within Jewry". Nietzsche also influenced Theodor Lessing.

Martin Buber was fascinated by Nietzsche, whom he praised as a heroic figure, and he strove to introduce "a Nietzschean perspective into Zionist affairs." In 1901, Buber, who had just been appointed the editor of Die Welt, the primary publication of the World Zionist Organization, published a poem in Zarathustrastil (a style reminiscent of Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra) calling for the return of Jewish literature, art and scholarship.

Max Nordau, an early Zionist orator and controversial racial anthropologist, insisted that Nietzsche had been insane since birth, and advocated "branding his disciples [...] as hysterical and imbecile."

Nietzsche, analytical psychology and psychoanalysis

Carl Jung, the psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology, recognized Nietzsche's profundity early on. "From the time Jung first became gripped by Nietzsche’s ideas as a student in Basel to his days as a leading figure in the psychoanalytic movement, Jung read, and increasingly developed, his own thought in a dialogue with the work of Nietzsche. … Untangling the exact influence of Nietzsche on Jung, however, is a complicated business. Jung never openly addressed the exact influence Nietzsche had on his own concepts, and when he did link his own ideas to Nietzsche’s, he almost never made it clear whether the idea in question was inspired by Nietzsche or whether he merely discovered the parallel at a later stage." In 1934, Jung held a lengthy and insightful seminar on Nietzsche's Zarathustra. In 1936, Jung explained that Germans of the present day had been seized or possessed by the psychic force known in Germanic mythology as Wotan, "the god of storm and frenzy, the unleasher of passions and the lust of battle"—Wotan being synonymous with Nietzsche's Dionysus, Jung said. A 12th-century stick found among the Bryggen inscriptions, Bergen, Norway bears a runic message by which the population called upon Thor and Wotan for help: Thor is asked to receive the reader, and Wotan to own them. "Nietzsche provided Jung both with the terminology (the Dionysian) and the case study (Zarathustra as an example of the Dionysian at work in the psyche) to help him put into words his thoughts about the spirit of his own age: an age confronted with an uprush of the Wotanic/Dionysian spirit in the collective unconscious. This, in a nutshell, is how Jung came to see Nietzsche, and explains why he was so fascinated by Nietzsche as a thinker."

Nietzsche had also an important influence on psychotherapist and founder of the school of individual psychology Alfred Adler. According to Ernest Jones, biographer and personal acquaintance of Sigmund Freud, Freud frequently referred to Nietzsche as having "more penetrating knowledge of himself than any man who ever lived or was likely to live". Yet Jones also reports that Freud emphatically denied that Nietzsche's writings influenced his own psychological discoveries; in the 1890s, Freud, whose education at the University of Vienna in the 1870s had included a strong relationship with Franz Brentano, his teacher in philosophy, from whom he had acquired an enthusiasm for Aristotle and Ludwig Feuerbach, was acutely aware of the possibility of convergence of his own ideas with those of Nietzsche and doggedly refused to read the philosopher as a result. In his excoriating — but also sympathetic — critique of psychoanalysis, The Psychoanalytic Movement, Ernest Gellner depicts Nietzsche as setting out the conditions for elaborating a realistic psychology, in contrast with the eccentrically implausible Enlightenment psychology of Hume and Smith, and assesses the success of Freud and the psychoanalytic movement as in large part based upon its success in meeting this "Nietzschean minimum".

Early 20th-century thinkers

Early twentieth-century thinkers who read or were influenced by Nietzsche include: philosophers Martin Heidegger, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Ernst Jünger, Theodor Adorno, Georg Brandes, Martin Buber, Karl Jaspers, Henri Bergson, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Leo Strauss, Michel Foucault, Julius Evola, Emil Cioran, Miguel de Unamuno, Lev Shestov, Ayn Rand, José Ortega y Gasset, Rudolf Steiner and Muhammad Iqbal; sociologists Ferdinand Tönnies and Max Weber; composers Richard Strauss, Alexander Scriabin, Gustav Mahler, and Frederick Delius; historians Oswald Spengler, Fernand Braudel and Paul Veyne, theologians Paul Tillich and Thomas J.J. Altizer; the occultists Aleister Crowley and Erwin Neutzsky-Wulff. Novelists Franz Kafka, Joseph Conrad, Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse, André Malraux, Nikos Kazantzakis, André Gide, Knut Hamsun, August Strindberg, James Joyce, D. H. Lawrence, Vladimir Bartol and Pío Baroja; psychologists Sigmund Freud, Otto Gross, C. G. Jung, Alfred Adler, Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, Rollo May and Kazimierz Dąbrowski; poets John Davidson, Rainer Maria Rilke, Wallace Stevens and William Butler Yeats; painters Salvador Dalí, Wassily Kandinsky, Pablo Picasso, Mark Rothko; playwrights George Bernard Shaw, Antonin Artaud, August Strindberg, and Eugene O'Neill; and authors H. P. Lovecraft, Olaf Stapledon, Menno ter Braak, Richard Wright, Robert E. Howard, and Jack London. American writer H. L. Mencken avidly read and translated Nietzsche's works and has gained the sobriquet "the American Nietzsche". In his book on Nietzsche, Mencken portrayed the philosopher as a proponent of anti-egalitarian aristocratic revolution, a depiction in sharp contrast with left-wing interpretations of Nietzsche. Nietzsche was declared an honorary anarchist by Emma Goldman, and he influenced other anarchists such as Guy Aldred, Rudolf Rocker, Max Cafard and John Moore.

The popular conservative writer, philosopher, poet, journalist and theological apologist of Catholicism G. K. Chesterton expressed contempt for Nietzsche's ideas, deeming his philosophy basically a poison or death-wish of Western culture:

I do not even think that a cosmopolitan contempt for patriotism is merely a matter of opinion, any more than I think that a Nietzscheite contempt for compassion is merely a matter of opinion. I think they are both heresies so horrible that their treatment must not be so much mental as moral, when it is not simply medical. Men are not always dead of a disease and men are not always damned by a delusion; but so far as they are touched by it they are destroyed by it.

— May 31, 1919, Illustrated London News

Thomas Mann's essays mention Nietzsche with respect and even adoration, although one of his final essays, "Nietzsche's Philosophy in the Light of Recent History", looks at his favorite philosopher through the lens of Nazism and World War II and ends up placing Nietzsche at a more critical distance. Many of Nietzsche's ideas, particularly on artists and aesthetics, are incorporated and explored throughout Mann's works. The theme of the aesthetic justification of existence Nietzsche introduced from his earliest writings, in "The Birth of Tragedy" declaring sublime art as the only metaphysical consolation of existence; and in the context of fascism and Nazism, the Nietzschean aestheticization of politics void of morality and ordered by caste hierarchy in service of the creative caste, has posed many problems and questions for thinkers in contemporary times. One of the characters in Mann's 1947 novel Doktor Faustus represents Nietzsche fictionally. In 1938 the German existentialist Karl Jaspers wrote the following about the influence of Nietzsche and Søren Kierkegaard:

The contemporary philosophical situation is determined by the fact that two philosophers, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, who did not count in their times and, for a long time, remained without influence in the history of philosophy, have continually grown in significance. Philosophers after Hegel have increasingly returned to face them, and they stand today unquestioned as the authentically great thinkers of their age. [...] The effect of both is immeasurably great, even greater in general thinking than in technical philosophy

— Jaspers, Reason and Existenz

Bertrand Russell in his History of Western Philosophy was scathing in his chapter on Nietzsche, asking whether his work might not be called the "mere power-phantasies of an invalid" and referring to Nietzsche as a "megalomaniac":

It is obvious that in his day-dreams he is a warrior, not a professor; all of the men he admires were military. His opinion of women, like every man's, is an objectification of his own emotion towards them, which is obviously one of fear. "Forget not thy whip"-- but nine women out of ten would get the whip away from him, and he knew it, so he kept away from women, and soothed his wounded vanity with unkind remarks. [...] [H]e is so full of fear and hatred that spontaneous love of mankind seems to him impossible. He has never conceived of the man who, with all the fearlessness and stubborn pride of the superman, nevertheless does not inflict pain because he has no wish to do so. Does any one suppose that Lincoln acted as he did from fear of hell? Yet to Nietzsche, Lincoln is abject, Napoleon magnificent. [...] I dislike Nietzsche because he likes the contemplation of pain, because he erects conceit into duty, because the men whom he most admires are conquerors, whose glory is cleverness in causing men to die. But I think the ultimate argument against his philosophy, as against any unpleasant but internally self-conscious ethic, lies not in an appeal to facts, but in an appeal to the emotions. Nietzsche despises universal love; I feel it the motive power to all that I desire as regards the world. His followers have had their innings, but we may hope that it is coming rapidly to an end.

— Russell, History of Western Philosophy

Likewise, the fictional valet Reginald Jeeves, created by author P. G. Wodehouse, is a fan of Baruch Spinoza, recommending his works to his employer, Bertie Wooster over those of Friedrich Nietzsche:

You would not enjoy Nietzsche, sir. He is fundamentally unsound.

— Wodehouse, Carry On Jeeves

Nietzsche after World War II

The appropriation of Nietzsche's work by the Nazis, combined with the rise of analytic philosophy, ensured that British and American academic philosophers would almost completely ignore him until at least 1950. Even George Santayana, an American philosopher whose life and work betray some similarity to Nietzsche's, dismissed Nietzsche in his 1916 Egotism in German Philosophy as a "prophet of Romanticism". Analytic philosophers, if they mentioned Nietzsche at all, characterized him as a literary figure rather than as a philosopher. Nietzsche's present stature in the English-speaking world owes much to the exegetical writings and improved Nietzsche translations by the Jewish-German, American philosopher Walter Kaufmann and the British scholar R.J. Hollingdale.

Nietzsche's influence on Continental philosophy increased dramatically after the Second World War, especially among the French intellectual Left and post-structuralists.

According to the philosopher René Girard, Nietzsche's greatest political legacy lies in his 20th-century French interpreters, among them Georges Bataille, Pierre Klossowski, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze (and Félix Guattari), and Jacques Derrida. This philosophical movement (originating with the work of Bataille) has been dubbed French Nietzscheanism. Foucault's later writings, for example, revise Nietzsche's genealogical method to develop anti-foundationalist theories of power that divide and fragment rather than unite polities (as evinced in the liberal tradition of political theory). Deleuze, arguably the foremost of Nietzsche's Leftist interpreters, used the much-maligned "will to power" thesis in tandem with Marxian notions of commodity surplus and Freudian ideas of desire to articulate concepts such as the rhizome and other "outsides" to state power as traditionally conceived.

Gilles Deleuze and Pierre Klossowski wrote monographs drawing new attention to Nietzsche's work, and a 1972 conference at Cérisy-la-Salle ranks as the most important event in France for a generation's reception of Nietzsche. In Germany interest in Nietzsche was revived from the 1980s onwards, particularly by the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, who has devoted several essays to Nietzsche. Ernst Nolte the German historian, in his literature analyzing fascism and Nazism, presented Nietzsche as a force of the Counter-Enlightenment and foe of all modern "emancipation politics", and Nolte's judgment generated impassioned dialogue.

In recent years, Nietzsche has also influenced members of the analytical philosophy tradition, such as Bernard Williams in his last finished book, Truth And Truthfulness: An Essay In Genealogy (2002). Prior to that Arthur Danto, with his book, Nietzsche as Philosopher (1965), presented what was the first full-length study of Nietzsche by an analytical philosopher. Then later, Alexander Nehamas, came out with his book, Nietzsche: Life as Literature (1985).