Diplomacy refers to spoken or written speech acts by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.

Diplomacy is the main instrument of foreign policy and global governance which represents the broader goals and strategies that guide a state's interactions with the rest of the world. International treaties, agreements, alliances, and other manifestations of international relations are usually the result of diplomatic negotiations and processes. Diplomats may also help shape a state by advising government officials.

Modern diplomatic methods, practices, and principles originated largely from 17th-century European custom. Beginning in the early 20th century, diplomacy became professionalized; the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, ratified by most of the world's sovereign states, provides a framework for diplomatic procedures, methods, and conduct. Most diplomacy is now conducted by accredited officials, such as envoys and ambassadors, through a dedicated foreign affairs office. Diplomats operate through diplomatic missions, most commonly consulates and embassies, and rely on a number of support staff; term diplomat is thus sometimes applied broadly to diplomatic and consular personnel and foreign ministry officials.

Etymology

The term diplomacy is derived from the 18th century French term diplomate (“diplomat” or “diplomatist”), based on the ancient Greek diplōma, which roughly means “an object folded in two". This reflected the practice of sovereigns providing a folded document to confer some sort of official privilege; prior to invention of the envelope, folding a document served to protect the privacy of its contents. The term was later applied to all official documents, such as those containing agreements between governments, and thus became identified with international relations.

History

Western Asia

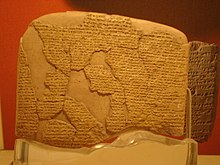

Some of the earliest known diplomatic records are the Amarna letters written between the pharaohs of the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt and the Amurru rulers of Canaan during the 14th century BCE. Peace treaties were concluded between the Mesopotamian city-states of Lagash and Umma around approximately 2100 BCE. Following the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC during the Nineteenth dynasty, the pharaoh of Egypt and the ruler of the Hittite Empire created one of the first known international peace treaties, which survives in stone tablet fragments, now generally called the Egyptian–Hittite peace treaty.

The ancient Greek city-states on some occasions dispatched envoys to negotiate specific issues, such as war and peace or commercial relations, but did not have diplomatic representatives regularly posted in each other's territory. However, some of the functions given to modern diplomatic representatives were fulfilled by a proxenos, a citizen of the host city who had friendly relations with another city, often through familial ties. In times of peace, diplomacy was even conducted with non-Hellenistic rivals such as the Achaemenid Empire of Persia, through it was ultimately conquered by Alexander the Great of Macedon. Alexander was also adept at diplomacy, realizing that the conquest of foreign cultures were be better achieved by having his Macedonian and Greek subjects intermingle and intermarry with native populations. For instance, Alexander took as his wife a Sogdian woman of Bactria, Roxana, after the siege of the Sogdian Rock, in order to placate the rebelling populace. Diplomacy remained a necessary tool of statecraft for the great Hellenistic states that succeeded Alexander's empire, such as the Ptolemaic Kingdom and Seleucid Empire, which fought several wars in the Near East and often negotiated peace treaties through marriage alliances.

Ottoman Empire

Relations with the Ottoman Empire were particularly important to Italian states, to which the Ottoman government was known as the Sublime Porte. The maritime republics of Genoa and Venice depended less and less upon their nautical capabilities, and more and more upon the perpetuation of good relations with the Ottomans. Interactions between various merchants, diplomats and clergymen hailing from the Italian and Ottoman empires helped inaugurate and create new forms of diplomacy and statecraft. Eventually the primary purpose of a diplomat, which was originally a negotiator, evolved into a persona that represented an autonomous state in all aspects of political affairs. It became evident that all other sovereigns felt the need to accommodate themselves diplomatically, due to the emergence of the powerful political environment of the Ottoman Empire. One could come to the conclusion that the atmosphere of diplomacy within the early modern period revolved around a foundation of conformity to Ottoman culture.

East Asia

One of the earliest realists in international relations theory was the 6th century BC military strategist Sun Tzu (d. 496 BC), author of The Art of War. He lived during a time in which rival states were starting to pay less attention to traditional respects of tutelage to the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1050–256 BC) figurehead monarchs while each vied for power and total conquest. However, a great deal of diplomacy in establishing allies, bartering land, and signing peace treaties was necessary for each warring state, and the idealized role of the "persuader/diplomat" developed.

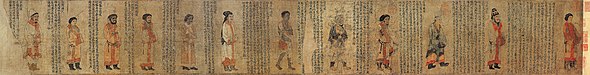

From the Battle of Baideng (200 BC) to the Battle of Mayi (133 BC), the Han Dynasty was forced to uphold a marriage alliance and pay an exorbitant amount of tribute (in silk, cloth, grain, and other foodstuffs) to the powerful northern nomadic Xiongnu that had been consolidated by Modu Shanyu. After the Xiongnu sent word to Emperor Wen of Han (r. 180–157) that they controlled areas stretching from Manchuria to the Tarim Basin oasis city-states, a treaty was drafted in 162 BC proclaiming that everything north of the Great Wall belong to nomads' lands, while everything south of it would be reserved for Han Chinese. The treaty was renewed no less than nine times, but did not restrain some Xiongnu tuqi from raiding Han borders. That was until the far-flung campaigns of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BC) which shattered the unity of the Xiongnu and allowed Han to conquer the Western Regions; under Wu, in 104 BC the Han armies ventured as far Fergana in Central Asia to battle the Yuezhi who had conquered Hellenistic Greek areas.

The Koreans and Japanese during the Chinese Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD) looked to the Chinese capital of Chang'an as the hub of civilization and emulated its central bureaucracy as the model of governance. The Japanese sent frequent embassies to China in this period, although they halted these trips in 894 when the Tang seemed on the brink of collapse. After the devastating An Shi Rebellion from 755 to 763, the Tang Dynasty was in no position to reconquer Central Asia and the Tarim Basin. After several conflicts with the Tibetan Empire spanning several different decades, the Tang finally made a truce and signed a peace treaty with them in 841.

In the 11th century during the Song Dynasty (960–1279), there were cunning ambassadors such as Shen Kuo and Su Song who achieved diplomatic success with the Liao Dynasty, the often hostile Khitan neighbor to the north. Both diplomats secured the rightful borders of the Song Dynasty through knowledge of cartography and dredging up old court archives. There was also a triad of warfare and diplomacy between these two states and the Tangut Western Xia Dynasty to the northwest of Song China (centered in modern-day Shaanxi). After warring with the Lý Dynasty of Vietnam from 1075 to 1077, Song and Lý made a peace agreement in 1082 to exchange the respective lands they had captured from each other during the war.

Long before the Tang and Song dynasties, the Chinese had sent envoys into Central Asia, India, and Persia, starting with Zhang Qian in the 2nd century BC. Another notable event in Chinese diplomacy was the Chinese embassy mission of Zhou Daguan to the Khmer Empire of Cambodia in the 13th century. Chinese diplomacy was a necessity in the distinctive period of Chinese exploration. Since the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD), the Chinese also became heavily invested in sending diplomatic envoys abroad on maritime missions into the Indian Ocean, to India, Persia, Arabia, East Africa, and Egypt. Chinese maritime activity was increased dramatically during the commercialized period of the Song Dynasty, with new nautical technologies, many more private ship owners, and an increasing amount of economic investors in overseas ventures.

During the Mongol Empire (1206–1294) the Mongols created something similar to today's diplomatic passport called paiza. The paiza were in three different types (golden, silver, and copper) depending on the envoy's level of importance. With the paiza, there came authority that the envoy can ask for food, transport, place to stay from any city, village, or clan within the empire with no difficulties.

From the 17th century the Qing Dynasty concluded a series of treaties with Czarist Russia, beginning with the Treaty of Nerchinsk in the year 1689. This was followed up by the Aigun Treaty and the Convention of Peking in the mid-19th century.

As European power spread around the world in the 18th and 19th centuries so too did its diplomatic model, and Asian countries adopted syncretic or European diplomatic systems. For example, as part of diplomatic negotiations with the West over control of land and trade in China in the 19th century after the First Opium War, the Chinese diplomat Qiying gifted intimate portraits of himself to representatives from Italy, England, the United States, and France.

Ancient India

Ancient India, with its kingdoms and dynasties, had a long tradition of diplomacy. The oldest treatise on statecraft and diplomacy, Arthashastra, is attributed to Kautilya (also known as Chanakya), who was the principal adviser to Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Maurya dynasty who ruled in the 3rd century BC. It incorporates a theory of diplomacy, of how in a situation of mutually contesting kingdoms, the wise king builds alliances and tries to checkmate his adversaries. The envoys sent at the time to the courts of other kingdoms tended to reside for extended periods of time, and Arthashastra contains advice on the deportment of the envoy, including the trenchant suggestion that 'he should sleep alone'. The highest morality for the king is that his kingdom should prosper.

New analysis of Arthashastra brings out that hidden inside the 6,000 aphorisms of prose (sutras) are pioneering political and philosophic concepts. It covers the internal and external spheres of statecraft, politics and administration. The normative element is the political unification of the geopolitical and cultural subcontinent of India. This work comprehensively studies state governance; it urges non-injury to living creatures, or malice, as well as compassion, forbearance, truthfulness, and uprightness. It presents a rajmandala (grouping of states), a model that places the home state surrounded by twelve competing entities which can either be potential adversaries or latent allies, depending on how relations with them are managed. This is the essence of realpolitik. It also offers four upaya (policy approaches): conciliation, gifts, rupture or dissent, and force. It counsels that war is the last resort, as its outcome is always uncertain. This is the first expression of the raison d’etat doctrine, as also of humanitarian law; that conquered people must be treated fairly, and assimilated.

Europe

Byzantine Empire

The key challenge to the Byzantine Empire was to maintain a set of relations between itself and its sundry neighbors, including the Georgians, Iberians, the Germanic peoples, the Bulgars, the Slavs, the Armenians, the Huns, the Avars, the Franks, the Lombards, and the Arabs, that embodied and so maintained its imperial status. All these neighbors lacked a key resource that Byzantium had taken over from Rome, namely a formalized legal structure. When they set about forging formal political institutions, they were dependent on the empire. Whereas classical writers are fond of making a sharp distinction between peace and war, for the Byzantines diplomacy was a form of war by other means. With a regular army of 120,000-140,000 men after the losses of the seventh century, the empire's security depended on activist diplomacy.

Byzantium's "Bureau of Barbarians" was the first foreign intelligence agency, gathering information on the empire's rivals from every imaginable source. While on the surface a protocol office—its main duty was to ensure foreign envoys were properly cared for and received sufficient state funds for their maintenance, and it kept all the official translators—it clearly had a security function as well. On Strategy, from the 6th century, offers advice about foreign embassies: "[Envoys] who are sent to us should be received honourably and generously, for everyone holds envoys in high esteem. Their attendants, however, should be kept under surveillance to keep them from obtaining any information by asking questions of our people."

Medieval and Early Modern Europe

In Europe, early modern diplomacy's origins are often traced to the states of Northern Italy in the early Renaissance, with the first embassies being established in the 13th century. Milan played a leading role, especially under Francesco Sforza who established permanent embassies to the other city states of Northern Italy. Tuscany and Venice were also flourishing centres of diplomacy from the 14th century onwards. It was in the Italian Peninsula that many of the traditions of modern diplomacy began, such as the presentation of an ambassador's credentials to the head of state.

Modernity

From Italy, the practice was spread across Europe. Milan was the first to send a representative to the court of France in 1455. However, Milan refused to host French representatives, fearing they would conduct espionage and intervene in its internal affairs. As foreign powers such as France and Spain became increasingly involved in Italian politics the need to accept emissaries was recognized. Soon the major European powers were exchanging representatives. Spain was the first to send a permanent representative; it appointed an ambassador to the Court of St. James's (i.e. England) in 1487. By the late 16th century, permanent missions became customary. The Holy Roman Emperor, however, did not regularly send permanent legates, as they could not represent the interests of all the German princes (who were in theory all subordinate to the Emperor, but in practice each independent).

In 1500-1700 rules of modern diplomacy were further developed. French replaced Latin from about 1715. The top rank of representatives was an ambassador. At that time an ambassador was a nobleman, the rank of the noble assigned varying with the prestige of the country he was delegated to. Strict standards developed for ambassadors, requiring they have large residences, host lavish parties, and play an important role in the court life of their host nation. In Rome, the most prized posting for a Catholic ambassador, the French and Spanish representatives would have a retinue of up to a hundred. Even in smaller posts, ambassadors were very expensive. Smaller states would send and receive envoys, who were a rung below ambassador. Somewhere between the two was the position of minister plenipotentiary.

Diplomacy was a complex affair, even more so than now. The ambassadors from each state were ranked by complex levels of precedence that were much disputed. States were normally ranked by the title of the sovereign; for Catholic nations the emissary from the Vatican was paramount, then those from the kingdoms, then those from duchies and principalities. Representatives from republics were ranked the lowest (which often angered the leaders of the numerous German, Scandinavian and Italian republics). Determining precedence between two kingdoms depended on a number of factors that often fluctuated, leading to near-constant squabbling.

Ambassadors were often nobles with little foreign experience and no expectation of a career in diplomacy. They were supported by their embassy staff. These professionals would be sent on longer assignments and would be far more knowledgeable than the higher-ranking officials about the host country. Embassy staff would include a wide range of employees, including some dedicated to espionage. The need for skilled individuals to staff embassies was met by the graduates of universities, and this led to a great increase in the study of international law, French, and history at universities throughout Europe.

At the same time, permanent foreign ministries began to be established in almost all European states to coordinate embassies and their staffs. These ministries were still far from their modern form, and many of them had extraneous internal responsibilities. Britain had two departments with frequently overlapping powers until 1782. They were also far smaller than they are currently. France, which boasted the largest foreign affairs department, had only some 70 full-time employees in the 1780s.

The elements of modern diplomacy slowly spread to Eastern Europe and Russia, arriving by the early 18th century. The entire edifice would be greatly disrupted by the French Revolution and the subsequent years of warfare. The revolution would see commoners take over the diplomacy of the French state, and of those conquered by revolutionary armies. Ranks of precedence were abolished. Napoleon also refused to acknowledge diplomatic immunity, imprisoning several British diplomats accused of scheming against France.

After the fall of Napoleon, the Congress of Vienna of 1815 established an international system of diplomatic rank. Disputes on precedence among nations (and therefore the appropriate diplomatic ranks used) were first addressed at the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818, but persisted for over a century until after World War II, when the rank of ambassador became the norm. In between that time, figures such as the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck were renowned for international diplomacy.

Diplomats and historians often refer to a foreign ministry by its address: the Ballhausplatz (Vienna), the Quai d’Orsay (Paris), the Wilhelmstraße (Berlin); Itamaraty (Brasil); and Foggy Bottom (Washington). For imperial Russia until 1917 it was the Choristers’ Bridge (St Petersburg), while "Consulta" referred to the Italian ministry of Foreign Affairs, based in the Palazzo della Consulta from 1874 to 1922.

Immunity

The sanctity of diplomats has long been observed, underpinning the modern concept of diplomatic immunity. While there have been a number of cases where diplomats have been killed, this is normally viewed as a great breach of honour. Genghis Khan and the Mongols were well known for strongly insisting on the rights of diplomats, and they would often wreak horrific vengeance against any state that violated these rights.

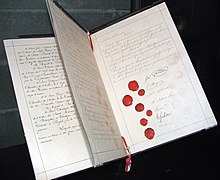

Diplomatic rights were established in the mid-17th century in Europe and have spread throughout the world. These rights were formalized by the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, which protects diplomats from being persecuted or prosecuted while on a diplomatic mission. If a diplomat does commit a serious crime while in a host country he or she may be declared as persona non grata (unwanted person). Such diplomats are then often tried for the crime in their homeland.

Diplomatic communications are also viewed as sacrosanct, and diplomats have long been allowed to carry documents across borders without being searched. The mechanism for this is the so-called "diplomatic bag" (or, in some countries, the "diplomatic pouch"). While radio and digital communication have become more standard for embassies, diplomatic pouches are still quite common and some countries, including the United States, declare entire shipping containers as diplomatic pouches to bring sensitive material (often building supplies) into a country.

In times of hostility, diplomats are often withdrawn for reasons of personal safety, as well as in some cases when the host country is friendly but there is a perceived threat from internal dissidents. Ambassadors and other diplomats are sometimes recalled temporarily by their home countries as a way to express displeasure with the host country. In both cases, lower-level employees still remain to actually do the business of diplomacy.

Espionage

Diplomacy is closely linked to espionage or gathering of intelligence. Embassies are bases for both diplomats and spies, and some diplomats are essentially openly acknowledged spies. For instance, the job of military attachés includes learning as much as possible about the military of the nation to which they are assigned. They do not try to hide this role and, as such, are only invited to events allowed by their hosts, such as military parades or air shows. There are also deep-cover spies operating in many embassies. These individuals are given fake positions at the embassy, but their main task is to illegally gather intelligence, usually by coordinating spy rings of locals or other spies. For the most part, spies operating out of embassies gather little intelligence themselves and their identities tend to be known by the opposition. If discovered, these diplomats can be expelled from an embassy, but for the most part counter-intelligence agencies prefer to keep these agents in situ and under close monitoring.

The information gathered by spies plays an increasingly important role in diplomacy. Arms-control treaties would be impossible without the power of reconnaissance satellites and agents to monitor compliance. Information gleaned from espionage is useful in almost all forms of diplomacy, everything from trade agreements to border disputes.

Resolution of problems

Various processes and procedures have evolved over time for handling diplomatic issues and disputes.

Arbitration and mediation

Nations sometimes resort to international arbitration when faced with a specific question or point of contention in need of resolution. For most of history, there were no official or formal procedures for such proceedings. They were generally accepted to abide by general principles and protocols related to international law and justice.

Sometimes these took the form of formal arbitrations and mediations. In such cases a commission of diplomats might be convened to hear all sides of an issue, and to come some sort of ruling based on international law.

In the modern era, much of this work is often carried out by the International Court of Justice at The Hague, or other formal commissions, agencies and tribunals, working under the United Nations. Below are some examples.

- The Hay-Herbert Treaty was enacted after the United States and Britain submitted a dispute to international mediation about the Canada–US border.

Conferences

Other times, resolutions were sought through the convening of international conferences. In such cases, there are fewer ground rules, and fewer formal applications of international law. However, participants are expected to guide themselves through principles of international fairness, logic, and protocol.

Some examples of these formal conferences are:

- Congress of Vienna (1815) – After Napoleon was defeated, there were many diplomatic questions waiting to be resolved. This included the shape of the political map of Europe, the disposition of political and nationalist claims of various ethnic groups and nationalities wishing to have some political autonomy, and the resolution of various claims by various European powers.

- The Congress of Berlin (June 13 – July 13, 1878) was a meeting of the European Great Powers' and the Ottoman Empire's leading statesmen in Berlin in 1878. In the wake of the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–78, the meeting's aim was to reorganize conditions in the Balkans.

Negotiations

Sometimes nations convene official negotiation processes to settle a specific dispute or specific issue between several nations which are parties to a dispute. These are similar to the conferences mentioned above, as there are technically no established rules or procedures. However, there are general principles and precedents which help define a course for such proceedings.

Some examples are

- Camp David Accords – Convened in 1978 by President Jimmy Carter of the United States, at Camp David to reach an agreement between Prime Minister Mechaem Begin of Israel and President Anwar Sadat of Egypt. After weeks of negotiation, agreement was reached and the accords were signed, later leading directly to the Egypt–Israel peace treaty of 1979.

- Treaty of Portsmouth – Enacted after President Theodore Roosevelt brought together the delegates from Russia and Japan, to settle the Russo-Japanese War. Roosevelt's personal intervention settled the conflict, and caused him to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

Small states

Small state diplomacy is receiving increasing attention in diplomatic studies and international relations. Small states are particularly affected by developments which are determined beyond their borders such as climate change, water security and shifts in the global economy. Diplomacy is the main vehicle by which small states are able to ensure that their goals are addressed in the global arena. These factors mean that small states have strong incentives to support international cooperation. But with limited resources at their disposal, conducting effective diplomacy poses unique challenges for small states.

Types

There are a variety of diplomatic categories and diplomatic strategies employed by organizations and governments to achieve their aims, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

Appeasement

Appeasement is a policy of making concessions to an aggressor in order to avoid confrontation; because of its failure to prevent World War 2, appeasement is not considered a legitimate tool of modern diplomacy.

Counterinsurgency

Counterinsurgency diplomacy, or expeditionary diplomacy, developed by diplomats deployed to civil-military stabilization efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan, employs diplomats at tactical and operational levels, outside traditional embassy environments and often alongside military or peacekeeping forces. Counterinsurgency diplomacy may provide political environment advice to local commanders, interact with local leaders, and facilitate the governance efforts, functions and reach of a host government.

Debt-trap

Debt-trap diplomacy is carried out in bilateral relations, with a powerful lending country seeking to saddle a borrowing nation with enormous debt so as to increase its leverage over it.[citation needed]

Economic

Economic diplomacy is the use of aid or other types of economic policy as a means to achieve a diplomatic agenda.

Gunboat

Gunboat diplomacy is the use of conspicuous displays of military power as a means of intimidation to influence others. Since it is inherently coercive, it typically lies near the edge between peace and war, and is usually exercised in the context of imperialism or hegemony. An emblematic example is the Don Pacifico Incident in 1850, in which the United Kingdom blockaded the Greek port of Piraeus in retaliation for the harming of a British subject and the failure of Greek government to provide him with restitution.

Hostage

Hostage diplomacy is the taking of hostages by a state or quasi-state actor to fulfill diplomatic goals. It is a type of asymmetric diplomacy often used by weaker states to pressure stronger ones. Hostage diplomacy has been practiced from prehistory to the present day.

Humanitarian

Humanitarian diplomacy is the set of activities undertaken by various actors with governments, (para)military organizations, or personalities in order to intervene or push intervention in a context where humanity is in danger. According to Antonio De Lauri, a Research Professor at the Chr. Michelsen Institute, humanitarian diplomacy "ranges from negotiating the presence of humanitarian organizations to negotiating access to civilian populations in need of protection. It involves monitoring assistance programs, promoting respect for international law, and engaging in advocacy in support of broader humanitarian goals".

Migration

Migration diplomacy is the use of human migration in a state's foreign policy. American political scientist Myron Weiner argued that international migration is intricately linked to states' international relations. More recently, Kelly Greenhill has identified how states may employ 'weapons of mass migration' against target states in their foreign relations. Migration diplomacy may involve the use of refugees, labor migrants, or diasporas in states' pursuit of international diplomacy goals. In the context of the Syrian Civil War, Syrian refugees were used in the context of Jordanian, Lebanese, and Turkish migration diplomacy.

Nuclear

Nuclear diplomacy is the area of diplomacy related to preventing nuclear proliferation and nuclear war. One of the most well-known (and most controversial) philosophies of nuclear diplomacy is mutually assured destruction (MAD).

Preventive

Preventive diplomacy is carried out through quiet means (as opposed to “gun-boat diplomacy”, which is backed by the threat of force, or “public diplomacy”, which makes use of publicity). It is also understood that circumstances may exist in which the consensual use of force (notably preventive deployment) might be welcomed by parties to a conflict with a view to achieving the stabilization necessary for diplomacy and related political processes to proceed. This is to be distinguished from the use of “persuasion”, “suasion”, “influence”, and other non-coercive approaches explored below.

Preventive diplomacy, in the view of one expert, is “the range of peaceful dispute resolution approaches mentioned in Article 33 of the UN Charter [on the pacific settlement of disputes] when applied before a dispute crosses the threshold to armed conflict.” It may take many forms, with different means employed. One form of diplomacy which may be brought to bear to prevent violent conflict (or to prevent its recurrence) is “quiet diplomacy”. When one speaks of the practice of quiet diplomacy, definitional clarity is largely absent. In part this is due to a lack of any comprehensive assessment of exactly what types of engagement qualify, and how such engagements are pursued. On the one hand, a survey of the literature reveals no precise understanding or terminology on the subject. On the other hand, concepts are neither clear nor discrete in practice. Multiple definitions are often invoked simultaneously by theorists, and the activities themselves often mix and overlap in practice.

Public

Public diplomacy is the exercise of influence through communication with the general public in another nation, rather than attempting to influence the nation's government directly. This communication may take the form of propaganda, or more benign forms such as citizen diplomacy, individual interactions between average citizens of two or more nations. Technological advances and the advent of digital diplomacy now allow instant communication with foreign citizens, and methods such as Facebook diplomacy and Twitter diplomacy are increasingly used by world leaders and diplomats.

Quiet

Also known as the "softly softly" approach, quiet diplomacy is the attempt to influence the behaviour of another state through secret negotiations or by refraining from taking a specific action. This method is often employed by states that lack alternative means to influence the target government, or that seek to avoid certain outcomes. For example, South Africa is described as engaging in quiet diplomacy with neighboring Zimbabwe to avoid appearing as "bullying" and subsequently engendering a hostile response. This approach can also be employed by more powerful states; U.S. President George W. Bush's nonattendance at the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development constituted a form of quiet diplomacy, namely in response to the lack of UN support for the U.S.' proposed invasion of Iraq.

Science

Science diplomacy is the use of scientific collaborations among nations to address common problems and to build constructive international partnerships. Many experts and groups use a variety of definitions for science diplomacy. However, science diplomacy has become an umbrella term to describe a number of formal or informal technical, research-based, academic or engineering exchanges, with notable examples including CERN, the International Space Station, and ITER.

Soft power

Soft power, sometimes called "hearts and minds diplomacy", as defined by Joseph Nye, is the cultivation of relationships, respect, or even admiration from others in order to gain influence, as opposed to more coercive approaches. Often and incorrectly confused with the practice of official diplomacy, soft power refers to non-state, culturally attractive factors that may predispose people to sympathize with a foreign culture based on affinity for its products, such as the American entertainment industry, schools and music. A country's soft power can come from three resources: its culture (in places where it is attractive to others), its political values (when it lives up to them at home and abroad), and its foreign policies (when they are seen as legitimate and having moral authority).

City

City diplomacy refers to cities using institutions and processes to engage relations with other actors on an international stage, with the aim of representing themselves and their interests to one another. Especially today, city administrations and networks are increasingly active in the realm of transnationally relevant questions and issues ranging from the climate crisis to migration and the promotion of smart technology. As such, cities and city networks may seek to address and re-shape national and sub-national conflicts, support their peers in the achievement of sustainable development, and achieve certain levels of regional integration and solidarity among each other. Whereas diplomacy pursued by nation-states is often said to be disconnected from the citizenry, city diplomacy fundamentally rests on its proximity to the latter and seeks to leverage these ties “to build international strategies integrating both their values and interests.”

Training

Most countries provide professional training for their diplomats and maintain institutions specifically for that purpose. Private institutions also exist as do establishments associated with organisations like the European Union and the United Nations.