From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Alchemy (from Arabic: al-kīmiyā; from Ancient Greek: khumeía) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first attested in a number of pseudepigraphical texts written in Greco-Roman Egypt during the first few centuries AD.

Alchemists attempted to purify, mature, and perfect certain materials. Common aims were chrysopoeia, the transmutation of "base metals" (e.g., lead) into "noble metals" (particularly gold); the creation of an elixir of immortality; and the creation of panaceas able to cure any disease. The perfection of the human body and soul was thought to result from the alchemical magnum opus ("Great Work"). The concept of creating the philosophers' stone was variously connected with all of these projects.

Islamic and European alchemists developed a basic set of laboratory techniques, theories, and terms, some of which are still in use today. They did not abandon the Ancient Greek philosophical idea that everything is composed of four elements, and they tended to guard their work in secrecy, often making use of cyphers and cryptic symbolism. In Europe, the 12th-century translations of medieval Islamic works on science and the rediscovery of Aristotelian philosophy gave birth to a flourishing tradition of Latin alchemy. This late medieval tradition of alchemy would go on to play a significant role in the development of early modern science (particularly chemistry and medicine).

Modern discussions of alchemy are generally split into an examination of its exoteric practical applications and its esoteric spiritual aspects, despite criticisms by scholars such as Eric J. Holmyard and Marie-Louise von Franz that they should be understood as complementary. The former is pursued by historians of the physical sciences, who examine the subject in terms of early chemistry, medicine, and charlatanism, and the philosophical and religious contexts in which these events occurred. The latter interests historians of esotericism, psychologists, and some philosophers and spiritualists. The subject has also made an ongoing impact on literature and the arts.

Etymology

The word alchemy comes from old French alquemie, alkimie, used in Medieval Latin as alchymia. This name was itself adopted from the Arabic word al-kīmiyā (الكيمياء). The Arabic al-kīmiyā in turn was a borrowing of the Late Greek term khēmeía (χημεία), also spelled khumeia (χυμεία) and khēmía (χημία), with al- being the Arabic definite article 'the'. Together this association can be interpreted as 'the process of transmutation

by which to fuse or reunite with the divine or original form'. Several

etymologies have been proposed for the Greek term. The first was

proposed by Zosimos of Panopolis (3rd–4th centuries), who derived it

from the name of a book, the Khemeu. Hermanm Diels argued in 1914 that it rather derived from χύμα, used to describe metallic objects formed by casting.

Others trace its roots to the Egyptian name kēme (hieroglyphic 𓆎𓅓𓏏𓊖 khmi ), meaning 'black earth', which refers to the fertile and auriferous soil of the Nile valley, as opposed to red desert sand. According to the Egyptologist Wallis Budge, the Arabic word al-kīmiyaʾ actually means "the Egyptian [science]", borrowing from the Coptic word for "Egypt", kēme (or its equivalent in the Mediaeval Bohairic dialect of Coptic, khēme). This Coptic word derives from Demotic kmỉ, itself from ancient Egyptian kmt.

The ancient Egyptian word referred to both the country and the colour

"black" (Egypt was the "black Land", by contrast with the "red Land",

the surrounding desert); so this etymology could also explain the

nickname "Egyptian black arts".

History

Alchemy

encompasses several philosophical traditions spanning some four

millennia and three continents. These traditions' general penchant for

cryptic and symbolic language makes it hard to trace their mutual

influences and "genetic" relationships. One can distinguish at least

three major strands, which appear to be mostly independent, at least in

their earlier stages: Chinese alchemy, centered in China; Indian alchemy, centered on the Indian subcontinent; and Western alchemy, which occurred around the Mediterranean and whose center has shifted over the millennia from Greco-Roman Egypt to the Islamic world, and finally medieval Europe. Chinese alchemy was closely connected to Taoism and Indian alchemy with the Dharmic faiths. In contrast, Western alchemy developed its philosophical system mostly independent of but influenced by various Western religions. It is still an open question whether these three strands share a common origin, or to what extent they influenced each other.

Hellenistic Egypt

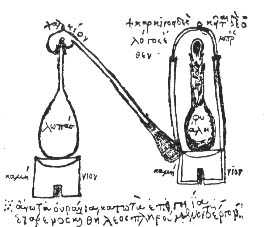

Ambix, cucurbit and retort of

Zosimos, from

Marcelin Berthelot,

Collection des anciens alchimistes grecs (3 vol., Paris, 1887–1888).

The start of Western alchemy may generally be traced to ancient and Hellenistic Egypt, where the city of Alexandria was a center of alchemical knowledge, and retained its pre-eminence through most of the Greek and Roman periods.

Following the work of André-Jean Festugière, modern scholars see

alchemical practice in the Roman Empire as originating from the Egyptian

goldsmith's art, Greek philosophy and different religious traditions. Tracing the origins of the alchemical art in Egypt is complicated by the pseudepigraphic nature of texts from the Greek alchemical corpus. The treatises of Zosimos of Panopolis, the earliest historically attested author (fl. c. 300 CE), can help in situating the other authors. Zosimus based his work on that of older alchemical authors, such as Mary the Jewess, Pseudo-Democritus, and Agathodaimon, but very little is known about any of these authors. The most complete of their works, The Four Books of Pseudo-Democritus, were probably written in the first century AD.

Recent scholarship tends to emphasize the testimony of Zosimus,

who traced the alchemical arts back to Egyptian metallurgical and

ceremonial practices.

It has also been argued that early alchemical writers borrowed the

vocabulary of Greek philosophical schools but did not implement any of

its doctrines in a systematic way. Zosimos of Panopolis wrote in the Final Abstinence (also known as the "Final Count").

Zosimos explains that the ancient practice of "tinctures" (the

technical Greek name for the alchemical arts) had been taken over by

certain "demons" who taught the art only to those who offered them

sacrifices. Since Zosimos also called the demons "the guardians of

places" (οἱ κατὰ τόπον ἔφοροι, hoi katà tópon éphoroi) and those who offered them sacrifices "priests" (ἱερέα, hieréa),

it is fairly clear that he was referring to the gods of Egypt and their

priests. While critical of the kind of alchemy he associated with the

Egyptian priests and their followers, Zosimos nonetheless saw the

tradition's recent past as rooted in the rites of the Egyptian temples.

Mythology – Zosimos of Panopolis asserted that alchemy dated back to Pharaonic Egypt where it was the domain of the priestly class, though there is little to no evidence for his assertion.

Alchemical writers used Classical figures from Greek, Roman, and

Egyptian mythology to illuminate their works and allegorize alchemical

transmutation. These included the pantheon of gods related to the Classical planets, Isis, Osiris, Jason, and many others.

The central figure in the mythology of alchemy is Hermes Trismegistus (or Thrice-Great Hermes). His name is derived from the god Thoth and his Greek counterpart Hermes. Hermes and his caduceus or serpent-staff, were among alchemy's principal symbols. According to Clement of Alexandria, he wrote what were called the "forty-two books of Hermes", covering all fields of knowledge. The Hermetica of Thrice-Great Hermes is generally understood to form the basis for Western alchemical philosophy and practice, called the hermetic philosophy by its early practitioners. These writings were collected in the first centuries of the common era.

Technology – The dawn of Western alchemy is sometimes associated with that of metallurgy, extending back to 3500 BC. Many writings were lost when the Roman emperor Diocletian ordered the burning of alchemical books

after suppressing a revolt in Alexandria (AD 292). Few original

Egyptian documents on alchemy have survived, most notable among them the

Stockholm papyrus and the Leyden papyrus X.

Dating from AD 250–300, they contained recipes for dyeing and making

artificial gemstones, cleaning and fabricating pearls, and manufacturing

of imitation gold and silver. These writings lack the mystical, philosophical elements of alchemy, but do contain the works of Bolus of Mendes (or Pseudo-Democritus), which aligned these recipes with theoretical knowledge of astrology and the classical elements. Between the time of Bolus and Zosimos, the change took place that transformed this metallurgy into a Hermetic art.

Philosophy – Alexandria acted as a melting pot for philosophies of Pythagoreanism, Platonism, Stoicism and Gnosticism which formed the origin of alchemy's character. An important example of alchemy's roots in Greek philosophy, originated by Empedocles and developed by Aristotle, was that all things in the universe were formed from only four elements: earth, air, water, and fire. According to Aristotle, each element had a sphere to which it belonged and to which it would return if left undisturbed.

The four elements of the Greek were mostly qualitative aspects of

matter, not quantitative, as our modern elements are; "...True alchemy

never regarded earth, air, water, and fire as corporeal or chemical

substances in the present-day sense of the word. The four elements are

simply the primary, and most general, qualities by means of which the

amorphous and purely quantitative substance of all bodies first reveals

itself in differentiated form." Later alchemists extensively developed the mystical aspects of this concept.

Alchemy coexisted alongside emerging Christianity. Lactantius believed Hermes Trismegistus had prophesied its birth. St Augustine later affirmed this in the 4th & 5th centuries, but also condemned Trismegistus for idolatry. Examples of Pagan, Christian, and Jewish alchemists can be found during this period.

Most of the Greco-Roman alchemists preceding Zosimos are known only by pseudonyms, such as Moses, Isis, Cleopatra, Democritus, and Ostanes. Others authors such as Komarios, and Chymes,

we only know through fragments of text. After AD 400, Greek alchemical

writers occupied themselves solely in commenting on the works of these

predecessors. By the middle of the 7th century alchemy was almost an entirely mystical discipline. It was at that time that Khalid Ibn Yazid

sparked its migration from Alexandria to the Islamic world,

facilitating the translation and preservation of Greek alchemical texts

in the 8th and 9th centuries.

Byzantium

Greek

alchemy is preserved in medieval Greek (Byzantine) manuscripts, and yet

historians have only relatively recently begun to pay attention to the

study and development of Greek alchemy in the Byzantine period.

India

The 2nd millennium BC text Vedas describe a connection between eternal life and gold. A considerable knowledge of metallurgy has been exhibited in a third-century CE text called Arthashastra

which provides ingredients of explosives (Agniyoga) and salts extracted

from fertile soils and plant remains (Yavakshara) such as saltpetre/nitre, perfume making (different qualities of perfumes are mentioned), granulated (refined) Sugar. Buddhist

texts from the 2nd to 5th centuries mention the transmutation of base

metals to gold. According to some scholars Greek alchemy may have

influenced Indian alchemy but there are no hard evidences to back this

claim.

The 11th-century Persian chemist and physician Abū Rayhān Bīrūnī, who visited Gujarat as part of the court of Mahmud of Ghazni, reported that they

have a science similar to alchemy which is quite peculiar to them, which in Sanskrit is called Rasāyana and in Persian Rasavātam. It means the art of obtaining/manipulating Rasa:

nectar, mercury, and juice. This art was restricted to certain

operations, metals, drugs, compounds, and medicines, many of which have

mercury as their core element. Its principles restored the health of

those who were ill beyond hope and gave back youth to fading old age.

The goals of alchemy in India included the creation of a divine body (Sanskrit divya-deham) and immortality while still embodied (Sanskrit jīvan-mukti).

Sanskrit alchemical texts include much material on the manipulation of

mercury and sulphur, that are homologized with the semen of the god Śiva

and the menstrual blood of the goddess Devī.

Some early alchemical writings seem to have their origins in the Kaula tantric schools associated to the teachings of the personality of Matsyendranath. Other early writings are found in the Jaina medical treatise Kalyāṇakārakam of Ugrāditya, written in South India in the early 9th century.

Two famous early Indian alchemical authors were Nāgārjuna Siddha and Nityanātha Siddha. Nāgārjuna Siddha was a Buddhist monk. His book, Rasendramangalam, is an example of Indian alchemy and medicine. Nityanātha Siddha wrote Rasaratnākara, also a highly influential work. In Sanskrit, rasa translates to "mercury", and Nāgārjuna Siddha was said to have developed a method of converting mercury into gold.

Scholarship on Indian alchemy is in the publication of The Alchemical Body by David Gordon White.

A modern bibliography on Indian alchemical studies has been written by White.

The contents of 39 Sanskrit alchemical treatises have been analysed in detail in G. Jan Meulenbeld's History of Indian Medical Literature.

The discussion of these works in HIML gives a summary of the contents

of each work, their special features, and where possible the evidence

concerning their dating. Chapter 13 of HIML, Various works on rasaśāstra and ratnaśāstra (or Various works on alchemy and gems)

gives brief details of a further 655 (six hundred and fifty-five)

treatises. In some cases Meulenbeld gives notes on the contents and

authorship of these works; in other cases references are made only to

the unpublished manuscripts of these titles.

A great deal remains to be discovered about Indian alchemical

literature. The content of the Sanskrit alchemical corpus has not yet

(2014) been adequately integrated into the wider general history of

alchemy.

Islamic world

15th-century artistic impression of

Jabir ibn Hayyan (Geber), Codici Ashburnhamiani 1166, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence.

After the Fall of the Roman Empire, the focus of alchemical development moved to the Islamic World. Much more is known about Islamic

alchemy because it was better documented: indeed, most of the earlier

writings that have come down through the years were preserved as Arabic

translations. The word alchemy itself was derived from the Arabic word al-kīmiyā (الكيمياء). The early Islamic world was a melting pot for alchemy. Platonic and Aristotelian

thought, which had already been somewhat appropriated into hermetical

science, continued to be assimilated during the late 7th and early 8th

centuries through Syriac translations and scholarship.

In the late ninth and early tenth centuries, the Arabic works attributed to Jābir ibn Hayyān (Latinized as "Geber" or "Geberus") introduced a new approach to alchemy. Paul Kraus, who wrote the standard reference work on Jabir, put it as follows:

To form an idea of the historical

place of Jabir's alchemy and to tackle the problem of its sources, it is

advisable to compare it with what remains to us of the alchemical

literature in the Greek language. One knows in which miserable state this literature reached us. Collected by Byzantine scientists

from the tenth century, the corpus of the Greek alchemists is a cluster

of incoherent fragments, going back to all the times since the third

century until the end of the Middle Ages.

The efforts of Berthelot and Ruelle to put a little order in this

mass of literature led only to poor results, and the later researchers,

among them in particular Mrs. Hammer-Jensen, Tannery, Lagercrantz, von

Lippmann, Reitzenstein, Ruska, Bidez, Festugière and others, could make

clear only few points of detail ....

The study of the Greek alchemists is not very encouraging. An

even surface examination of the Greek texts shows that a very small part

only was organized according to true experiments of laboratory: even

the supposedly technical writings, in the state where we find them

today, are unintelligible nonsense which refuses any interpretation.

It is different with Jabir's alchemy. The relatively clear description

of the processes and the alchemical apparati, the methodical

classification of the substances, mark an experimental spirit which is

extremely far away from the weird and odd esotericism of the Greek

texts. The theory on which Jabir supports his operations is one of

clearness and of an impressive unity. More than with the other Arab

authors, one notes with him a balance between theoretical teaching and

practical teaching, between the 'ilm and the amal. In vain one would seek in the Greek texts a work as systematic as that which is presented, for example, in the Book of Seventy.

Islamic philosophers also made great contributions to alchemical

hermeticism. The most influential author in this regard was arguably

Jabir. Jabir's ultimate goal was Takwin,

the artificial creation of life in the alchemical laboratory, up to,

and including, human life. He analyzed each Aristotelian element in

terms of four basic qualities of hotness, coldness, dryness, and moistness.

According to Jabir, in each metal two of these qualities were interior

and two were exterior. For example, lead was externally cold and dry,

while gold was hot and moist. Thus, Jabir theorized, by rearranging the

qualities of one metal, a different metal would result. By this reasoning, the search for the philosopher's stone was introduced to Western alchemy. Jabir developed an elaborate numerology

whereby the root letters of a substance's name in Arabic, when treated

with various transformations, held correspondences to the element's

physical properties.

The elemental system used in medieval alchemy also originated

with Jabir. His original system consisted of seven elements, which

included the five classical elements (aether, air, earth, fire, and water) in addition to two chemical elements representing the metals: sulphur, "the stone which burns", which characterized the principle of combustibility, and mercury, which contained the idealized principle of metallic properties.

Shortly thereafter, this evolved into eight elements, with the Arabic

concept of the three metallic principles: sulphur giving flammability or

combustion, mercury giving volatility and stability, and salt giving solidity. The atomic theory of corpuscularianism,

where all physical bodies possess an inner and outer layer of minute

particles or corpuscles, also has its origins in the work of Jabir.

From the 9th to 14th centuries, alchemical theories faced criticism from a variety of practical Muslim chemists, including Alkindus, Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī, Avicenna and Ibn Khaldun. In particular, they wrote refutations against the idea of the transmutation of metals.

East Asia

Taoist alchemists often use this alternate version of the

taijitu.

Whereas European alchemy eventually centered on the transmutation of

base metals into noble metals, Chinese alchemy had a more obvious

connection to medicine. The philosopher's stone of European alchemists can be compared to the Grand Elixir of Immortality

sought by Chinese alchemists. In the hermetic view, these two goals

were not unconnected, and the philosopher's stone was often equated with

the universal panacea; therefore, the two traditions may have had more in common than initially appears.

Black powder may have been an important invention of Chinese alchemists. As previously stated above, Chinese alchemy was more related to medicine. It is said that the Chinese invented gunpowder while trying to find a potion for eternal life. Described in 9th-century texts and used in fireworks in China by the 10th century, it was used in cannons by 1290. From China, the use of gunpowder spread to Japan, the Mongols,

the Muslim world, and Europe. Gunpowder was used by the Mongols against

the Hungarians in 1241, and in Europe by the 14th century.

Chinese alchemy was closely connected to Taoist forms of traditional Chinese medicine, such as Acupuncture and Moxibustion. In the early Song dynasty, followers of this Taoist idea (chiefly the elite and upper class) would ingest mercuric sulfide, which, though tolerable in low levels, led many to suicide.

Thinking that this consequential death would lead to freedom and access

to the Taoist heavens, the ensuing deaths encouraged people to eschew

this method of alchemy in favor of external sources (the aforementioned Tai Chi Chuan, mastering of the qi, etc.) Chinese alchemy was introduced to the West by Obed Simon Johnson.

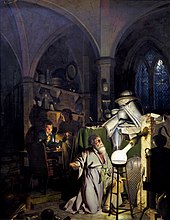

Medieval Europe

"An illuminated page from a book on alchemical processes and receipts", ca. 15th century.

The introduction of alchemy to Latin Europe may be dated to 11 February 1144, with the completion of Robert of Chester's translation of the Arabic Book of the Composition of Alchemy.

Although European craftsmen and technicians pre-existed, Robert notes

in his preface that alchemy (though here still referring to the elixir rather than to the art itself)

was unknown in Latin Europe at the time of his writing. The translation

of Arabic texts concerning numerous disciplines including alchemy

flourished in 12th-century Toledo, Spain, through contributors like Gerard of Cremona and Adelard of Bath. Translations of the time included the Turba Philosophorum, and the works of Avicenna and Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi.

These brought with them many new words to the European vocabulary for

which there was no previous Latin equivalent. Alcohol, carboy, elixir,

and athanor are examples.

Meanwhile, theologian contemporaries of the translators made

strides towards the reconciliation of faith and experimental

rationalism, thereby priming Europe for the influx of alchemical

thought. The 11th-century St Anselm

put forth the opinion that faith and rationalism were compatible and

encouraged rationalism in a Christian context. In the early 12th

century, Peter Abelard

followed Anselm's work, laying down the foundation for acceptance of

Aristotelian thought before the first works of Aristotle had reached the

West. In the early 13th century, Robert Grosseteste

used Abelard's methods of analysis and added the use of observation,

experimentation, and conclusions when conducting scientific

investigations. Grosseteste also did much work to reconcile Platonic and

Aristotelian thinking.

Through much of the 12th and 13th centuries, alchemical knowledge

in Europe remained centered on translations, and new Latin

contributions were not made. The efforts of the translators were

succeeded by that of the encyclopaedists. In the 13th century, Albertus Magnus and Roger Bacon

were the most notable of these, their work summarizing and explaining

the newly imported alchemical knowledge in Aristotelian terms. Albertus Magnus, a Dominican friar, is known to have written works such as the Book of Minerals

where he observed and commented on the operations and theories of

alchemical authorities like Hermes and Democritus and unnamed alchemists

of his time. Albertus critically compared these to the writings of

Aristotle and Avicenna, where they concerned the transmutation of

metals. From the time shortly after his death through to the 15th

century, more than 28 alchemical tracts were misattributed to him, a

common practice giving rise to his reputation as an accomplished

alchemist. Likewise, alchemical texts have been attributed to Albert's student Thomas Aquinas.

Roger Bacon, a Franciscan friar who wrote on a wide variety of topics including optics, comparative linguistics, and medicine, composed his Great Work (Latin: Opus Majus) for Pope Clement IV as part of a project towards rebuilding the medieval university

curriculum to include the new learning of his time. While alchemy was

not more important to him than other sciences and he did not produce

allegorical works on the topic, he did consider it and astrology to be

important parts of both natural philosophy and theology and his

contributions advanced alchemy's connections to soteriology

and Christian theology. Bacon's writings integrated morality,

salvation, alchemy, and the prolongation of life. His correspondence

with Clement highlighted this, noting the importance of alchemy to the

papacy.

Like the Greeks before him, Bacon acknowledged the division of alchemy

into practical and theoretical spheres. He noted that the theoretical

lay outside the scope of Aristotle, the natural philosophers, and all

Latin writers of his time. The practical confirmed the theoretical, and

Bacon advocated its uses in natural science and medicine.

In later European legend, he became an archmage. In particular, along

with Albertus Magnus, he was credited with the forging of a brazen head capable of answering its owner's questions.

Soon after Bacon, the influential work of Pseudo-Geber (sometimes identified as Paul of Taranto) appeared. His Summa Perfectionis

remained a staple summary of alchemical practice and theory through the

medieval and renaissance periods. It was notable for its inclusion of

practical chemical operations alongside sulphur-mercury theory, and the

unusual clarity with which they were described.

By the end of the 13th century, alchemy had developed into a fairly

structured system of belief. Adepts believed in the macrocosm-microcosm

theories of Hermes, that is to say, they believed that processes that

affect minerals and other substances could have an effect on the human

body (for example, if one could learn the secret of purifying gold, one

could use the technique to purify the human soul).

They believed in the four elements and the four qualities as described

above, and they had a strong tradition of cloaking their written ideas

in a labyrinth of coded jargon

set with traps to mislead the uninitiated. Finally, the alchemists

practiced their art: they actively experimented with chemicals and made observations and theories

about how the universe operated. Their entire philosophy revolved

around their belief that man's soul was divided within himself after the

fall of Adam. By purifying the two parts of man's soul, man could be

reunited with God.

In the 14th century, alchemy became more accessible to Europeans

outside the confines of Latin speaking churchmen and scholars.

Alchemical discourse shifted from scholarly philosophical debate to an

exposed social commentary on the alchemists themselves. Dante, Piers Plowman, and Chaucer all painted unflattering pictures of alchemists as thieves and liars. Pope John XXII's 1317 edict, Spondent quas non-exhibent forbade the false promises of transmutation made by pseudo-alchemists.

In 1403, Henry IV of England banned the practice of multiplying metals

(although it was possible to buy a licence to attempt to make gold

alchemically, and a number were granted by Henry VI and Edward IV).

These critiques and regulations centered more around pseudo-alchemical

charlatanism than the actual study of alchemy, which continued with an

increasingly Christian tone. The 14th century saw the Christian imagery

of death and resurrection employed in the alchemical texts of Petrus Bonus, John of Rupescissa, and in works written in the name of Raymond Lull and Arnold of Villanova.

Nicolas Flamel is a well-known alchemist, but a good example of pseudepigraphy,

the practice of giving your works the name of someone else, usually

more famous. Although the historical Flamel existed, the writings and

legends assigned to him only appeared in 1612.

Flamel was not a religious scholar as were many of his predecessors,

and his entire interest in the subject revolved around the pursuit of

the philosopher's stone.

His work spends a great deal of time describing the processes and

reactions, but never actually gives the formula for carrying out the

transmutations. Most of 'his' work was aimed at gathering alchemical

knowledge that had existed before him, especially as regarded the

philosopher's stone. Through the 14th and 15th centuries, alchemists were much like Flamel: they concentrated on looking for the philosophers' stone. Bernard Trevisan and George Ripley made similar contributions. Their cryptic allusions and symbolism led to wide variations in interpretation of the art.

Renaissance and early modern Europe

Page from alchemic treatise of

Ramon Llull, 16th century

The red sun rising over the city, the final illustration of 16th-century alchemical text,

Splendor Solis. The word

rubedo, meaning "redness", was adopted by alchemists and signalled alchemical success, and the end of the great work.

During the Renaissance,

Hermetic and Platonic foundations were restored to European alchemy.

The dawn of medical, pharmaceutical, occult, and entrepreneurial

branches of alchemy followed.

In the late 15th century, Marsilio Ficino translated the Corpus Hermeticum

and the works of Plato into Latin. These were previously unavailable to

Europeans who for the first time had a full picture of the alchemical

theory that Bacon had declared absent. Renaissance Humanism and Renaissance Neoplatonism guided alchemists away from physics to refocus on mankind as the alchemical vessel.

Esoteric systems developed that blended alchemy into a broader

occult Hermeticism, fusing it with magic, astrology, and Christian

cabala. A key figure in this development was German Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (1486–1535), who received his Hermetic education in Italy in the schools of the humanists. In his De Occulta Philosophia, he attempted to merge Kabbalah, Hermeticism, and alchemy. He was instrumental in spreading this new blend of Hermeticism outside the borders of Italy.

Philippus Aureolus Paracelsus,

(Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, 1493–1541) cast alchemy into a

new form, rejecting some of Agrippa's occultism and moving away from chrysopoeia.

Paracelsus pioneered the use of chemicals and minerals in medicine and

wrote, "Many have said of Alchemy, that it is for the making of gold and

silver. For me such is not the aim, but to consider only what virtue

and power may lie in medicines."

His hermetical views were that sickness and health in the body

relied on the harmony of man the microcosm and Nature the macrocosm. He

took an approach different from those before him, using this analogy not

in the manner of soul-purification but in the manner that humans must

have certain balances of minerals in their bodies, and that certain

illnesses of the body had chemical remedies that could cure them. Iatrochemistry refers to the pharmaceutical applications of alchemy championed by Paracelsus.

John Dee

(13 July 1527 – December, 1608) followed Agrippa's occult tradition.

Although better known for angel summoning, divination, and his role as astrologer, cryptographer, and consultant to Queen Elizabeth I, Dee's alchemical Monas Hieroglyphica,

written in 1564 was his most popular and influential work. His writing

portrayed alchemy as a sort of terrestrial astronomy in line with the

Hermetic axiom As above so below.

During the 17th century, a short-lived "supernatural" interpretation of

alchemy became popular, including support by fellows of the Royal Society: Robert Boyle and Elias Ashmole.

Proponents of the supernatural interpretation of alchemy believed that

the philosopher's stone might be used to summon and communicate with

angels.

Entrepreneurial opportunities were common for the alchemists of

Renaissance Europe. Alchemists were contracted by the elite for

practical purposes related to mining, medical services, and the

production of chemicals, medicines, metals, and gemstones. Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor,

in the late 16th century, famously received and sponsored various

alchemists at his court in Prague, including Dee and his associate Edward Kelley. King James IV of Scotland, Julius, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, Henry V, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, Augustus, Elector of Saxony, Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn, and Maurice, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel all contracted alchemists. John's son Arthur Dee worked as a court physician to Michael I of Russia and Charles I of England but also compiled the alchemical book Fasciculus Chemicus.

Although most of these appointments were legitimate, the trend of pseudo-alchemical fraud continued through the Renaissance. Betrüger

would use sleight of hand, or claims of secret knowledge to make money

or secure patronage. Legitimate mystical and medical alchemists such as Michael Maier and Heinrich Khunrath wrote about fraudulent transmutations, distinguishing themselves from the con artists. False alchemists were sometimes prosecuted for fraud.

The terms "chemia" and "alchemia" were used as synonyms in the

early modern period, and the differences between alchemy, chemistry and

small-scale assaying and metallurgy were not as neat as in the present

day. There were important overlaps between practitioners, and trying to

classify them into alchemists, chemists and craftsmen is anachronistic.

For example, Tycho Brahe (1546–1601), an alchemist better known for his astronomical and astrological investigations, had a laboratory built at his Uraniborg observatory/research institute. Michael Sendivogius (Michał Sędziwój, 1566–1636), a Polish alchemist, philosopher, medical doctor and pioneer of chemistry wrote mystical works but is also credited with distilling oxygen in a lab sometime around 1600. Sendivogious taught his technique to Cornelius Drebbel who, in 1621, applied this in a submarine. Isaac Newton devoted considerably more of his writing to the study of alchemy (see Isaac Newton's occult studies) than he did to either optics or physics. Other early modern alchemists who were eminent in their other studies include Robert Boyle, and Jan Baptist van Helmont. Their Hermeticism complemented rather than precluded their practical achievements in medicine and science.

Later modern period

The decline of European alchemy was brought about by the rise of

modern science with its emphasis on rigorous quantitative

experimentation and its disdain for "ancient wisdom". Although the seeds

of these events were planted as early as the 17th century, alchemy

still flourished for some two hundred years, and in fact may have

reached its peak in the 18th century. As late as 1781 James Price

claimed to have produced a powder that could transmute mercury into

silver or gold. Early modern European alchemy continued to exhibit a

diversity of theories, practices, and purposes: "Scholastic and

anti-Aristotelian, Paracelsian and anti-Paracelsian, Hermetic,

Neoplatonic, mechanistic, vitalistic, and more—plus virtually every

combination and compromise thereof."

Robert Boyle

(1627–1691) pioneered the scientific method in chemical investigations.

He assumed nothing in his experiments and compiled every piece of

relevant data. Boyle would note the place in which the experiment was

carried out, the wind characteristics, the position of the Sun and Moon,

and the barometer reading, all just in case they proved to be relevant.

This approach eventually led to the founding of modern chemistry in the

18th and 19th centuries, based on revolutionary discoveries and ideas

of Lavoisier and John Dalton.

Beginning around 1720, a rigid distinction began to be drawn for the first time between "alchemy" and "chemistry".

By the 1740s, "alchemy" was now restricted to the realm of gold making,

leading to the popular belief that alchemists were charlatans, and the

tradition itself nothing more than a fraud. In order to protect the developing science of modern chemistry from the

negative censure to which alchemy was being subjected, academic writers

during the 18th-century scientific Enlightenment attempted, for the

sake of survival, to divorce and separate the "new" chemistry from the

"old" practices of alchemy. This move was mostly successful, and the

consequences of this continued into the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries.

During the occult revival of the early 19th century, alchemy received new attention as an occult science.

The esoteric or occultist school, which arose during the 19th century,

held (and continues to hold) the view that the substances and operations

mentioned in alchemical literature are to be interpreted in a spiritual

sense, and it downplays the role of the alchemy as a practical

tradition or protoscience.

This interpretation further forwarded the view that alchemy is an art

primarily concerned with spiritual enlightenment or illumination, as

opposed to the physical manipulation of apparatus and chemicals, and

claims that the obscure language of the alchemical texts were an

allegorical guise for spiritual, moral or mystical processes.

In the 19th-century revival of alchemy, the two most seminal figures were Mary Anne Atwood and Ethan Allen Hitchcock,

who independently published similar works regarding spiritual alchemy.

Both forwarded a completely esoteric view of alchemy, as Atwood claimed:

"No modern art or chemistry, notwithstanding all its surreptitious

claims, has any thing in common with Alchemy." Atwood's work influenced subsequent authors of the occult revival including Eliphas Levi, Arthur Edward Waite, and Rudolf Steiner. Hitchcock, in his Remarks Upon Alchymists

(1855) attempted to make a case for his spiritual interpretation with

his claim that the alchemists wrote about a spiritual discipline under a

materialistic guise in order to avoid accusations of blasphemy from the

church and state. In 1845, Baron Carl Reichenbach, published his studies on Odic force, a concept with some similarities to alchemy, but his research did not enter the mainstream of scientific discussion.

In 1946, Louis Cattiaux

published the Message Retrouvé, a work that was at once philosophical,

mystical and highly influenced by alchemy. In his lineage, many

researchers, including Emmanuel and Charles d'Hooghvorst, are updating

alchemical studies in France and Belgium.

Women

Several women appear in the earliest history of alchemy. Michael Maier names Mary the Jewess, Cleopatra the Alchemist, Medera, and Taphnutia as the four women who knew how to make the philosopher's stone. Zosimos' sister Theosebia (later known as Euthica the Arab) and Isis the Prophetess also played a role in early alchemical texts.

The first alchemist whose name we know was Mary the Jewess (c. 200 A.D.).

Early sources claim that Mary (or Maria) devised a number of

improvements to alchemical equipment and tools as well as novel

techniques in chemistry.

Her best known advances were in heating and distillation processes. The

laboratory water-bath, known eponymously (especially in France) as the bain-marie, is said to have been invented or at least improved by her.

Essentially a double-boiler, it was (and is) used in chemistry for

processes that require gentle heating. The tribikos (a modified

distillation apparatus) and the kerotakis (a more intricate apparatus

used especially for sublimations) are two other advancements in the

process of distillation that are credited to her. Although we have no writing from Mary herself, she is known from the early-fourth-century writings of Zosimos of Panopolis.

Due to the proliferation of pseudepigrapha

and anonymous works, it is difficult to know which of the alchemists

were actually women. After the Greco-Roman period, women's names appear

less frequently in the alchemical literature. Women vacate the history

of alchemy during the medieval and renaissance periods, aside from the

fictitious account of Perenelle Flamel. Mary Anne Atwood's A Suggestive Inquiry into the Hermetic Mystery (1850) marks their return during the nineteenth-century occult revival.

Modern historical research

The history of alchemy has become a significant and recognized subject of academic study.

As the language of the alchemists is analyzed, historians are becoming

more aware of the intellectual connections between that discipline and

other facets of Western cultural history, such as the evolution of

science and philosophy, the sociology and psychology of the intellectual communities, kabbalism, spiritualism, Rosicrucianism, and other mystic movements. Institutions involved in this research include The Chymistry of Isaac Newton project at Indiana University, the University of Exeter Centre for the Study of Esotericism (EXESESO), the European Society for the Study of Western Esotericism (ESSWE), and the University of Amsterdam's

Sub-department for the History of Hermetic Philosophy and Related

Currents. A large collection of books on alchemy is kept in the Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica

in Amsterdam. A recipe found in a mid-19th-century kabbalah based book

features step by step instructions on turning copper into gold. The

author attributed this recipe to an ancient manuscript he located.

Journals which publish regularly on the topic of Alchemy include 'Ambix', published by the Society for the History of Alchemy and Chemistry, and 'Isis', published by The History of Science Society.

Core concepts

Mandala illustrating common alchemical concepts, symbols, and processes. From Spiegel der Kunst und Natur.

Western alchemical theory corresponds to the worldview of late antiquity in which it was born. Concepts were imported from Neoplatonism and earlier Greek cosmology. As such, the classical elements appear in alchemical writings, as do the seven classical planets and the corresponding seven metals of antiquity.

Similarly, the gods of the Roman pantheon who are associated with these

luminaries are discussed in alchemical literature. The concepts of prima materia and anima mundi are central to the theory of the philosopher's stone.

Magnum opus

The Great Work of Alchemy is often described as a series of four stages represented by colors.

Modernity

Due

to the complexity and obscurity of alchemical literature, and the

18th-century disappearance of remaining alchemical practitioners into

the area of chemistry, the general understanding of alchemy has been

strongly influenced by several distinct and radically different

interpretations. Those focusing on the exoteric, such as historians of science Lawrence M. Principe and William R. Newman,

have interpreted the 'decknamen' (or code words) of alchemy as physical

substances. These scholars have reconstructed physicochemical

experiments that they say are described in medieval and early modern

texts. At the opposite end of the spectrum, focusing on the esoteric, scholars, such as Florin George Călian and Anna Marie Roos,

who question the reading of Principe and Newman, interpret these same

decknamen as spiritual, religious, or psychological concepts.

New interpretations of alchemy are still perpetuated, sometimes merging in concepts from New Age or radical environmentalism movements. Groups like the Rosicrucians and Freemasons

have a continued interest in alchemy and its symbolism. Since the

Victorian revival of alchemy, "occultists reinterpreted alchemy as a

spiritual practice, involving the self-transformation of the

practitioner and only incidentally or not at all the transformation of

laboratory substances", which has contributed to a merger of magic and alchemy in popular thought.

Esoteric interpretations of historical texts

In the eyes of a variety of modern esoteric and Neo-Hermeticist

practitioners, alchemy is fundamentally spiritual. In this

interpretation, transmutation of lead into gold is presented as an

analogy for personal transmutation, purification, and perfection.

According to this view, early alchemists such as Zosimos of Panopolis (c. 300 AD) highlighted the spiritual nature of the alchemical quest, symbolic of a religious regeneration of the human soul.

This approach is held to have continued in the Middle Ages, as

metaphysical aspects, substances, physical states, and material

processes are supposed to have been used as metaphors for spiritual

entities, spiritual states, and, ultimately, transformation. In this

sense, the literal meanings of 'Alchemical Formulas' were like a veil,

hiding their true spiritual philosophy.

In the Neo-Hermeticist interpretation, both the transmutation of common

metals into gold and the universal panacea are held to symbolize

evolution from an imperfect, diseased, corruptible, and ephemeral state

toward a perfect, healthy, incorruptible, and everlasting state, so the

philosopher's stone then represented a mystic key that would make this

evolution possible. Applied to the alchemist, the twin goal symbolized

their evolution from ignorance to enlightenment, and the stone

represented a hidden spiritual truth or power that would lead to that

goal. In texts that are held to have been written according to this

view, the cryptic alchemical symbols,

diagrams, and textual imagery of late alchemical works are supposed to

contain multiple layers of meanings, allegories, and references to other

equally cryptic works; which must be laboriously decoded to discover

their true meaning.

In his 1766 Alchemical Catechism, Théodore Henri de Tschudi denotes that the usage of the metals was merely symbolic:

Q. When the Philosophers speak of gold and silver, from which they

extract their matter, are we to suppose that they refer to the vulgar

gold and silver?

A. By no means; vulgar silver and gold are dead, while those of the Philosophers are full of life.

Psychology

Alchemical

symbolism has been important in analytical psychology and was revived

and popularized from near extinction by the Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung. Jung was initially confounded and at odds with alchemy and its images but after being given a copy of The Secret of the Golden Flower, a Chinese alchemical text translated by his friend Richard Wilhelm,

he discovered a direct correlation or parallel between the symbolic

images in the alchemical drawings and the inner, symbolic images coming

up in the dreams, visions or imaginations of his patients. He observed

these alchemical images occurring during the psychic process of

transformation, a process that Jung called "individuation." Specifically, he regarded the conjuring up of images of gold or Lapis as symbolic expressions of the origin and goal of this "process of individuation." Together with his alchemical mystica soror (mystical sister) Jungian Swiss analyst Marie-Louise von Franz, Jung began collecting old alchemical texts, compiled a lexicon of key phrases with cross-references,

and pored over them. The volumes of work he wrote brought new light

into understanding the art of transubstantiation and renewed alchemy's

popularity as a symbolic process of coming into wholeness as a human

being where opposites are brought into contact and inner and outer,

spirit and matter are reunited in the hieros gamos

or divine marriage. His writings are influential in general psychology

but especially to those who have an interest in understanding the

importance of dreams, symbols, and the unconscious archetypal forces (archetypes) that comprise all psychic life.

Both von Franz and Jung have contributed significantly to the

subject and work of alchemy and its continued presence in psychology as

well as contemporary culture. Among the volumes Jung wrote on alchemy,

his magnum opus is Volume 14 of his Collected Works, Mysterium Coniunctionis.

Literature

Alchemy has had a long-standing relationship with art, seen both in alchemical texts and in mainstream entertainment. Literary alchemy appears throughout the history of English literature from Shakespeare to J. K. Rowling, and also the popular Japanese manga Fullmetal Alchemist.

Here, characters or plot structure follow an alchemical magnum opus. In

the 14th century, Chaucer began a trend of alchemical satire that can

still be seen in recent fantasy works like those of the late Sir Terry Pratchett.

Visual artists had a similar relationship with alchemy. While

some of them used alchemy as a source of satire, others worked with the

alchemists themselves or integrated alchemical thought or symbols in

their work. Music was also present in the works of alchemists and

continues to influence popular performers. In the last hundred years,

alchemists have been portrayed in a magical and spagyric role in fantasy

fiction, film, television, novels, comics and video games.

Science

One goal of alchemy, the transmutation of base substances into gold,

is now known to be impossible by chemical means but possible by physical

means. Although not financially worthwhile, Gold was synthesized in particle accelerators as early as 1941.