Landscape ecology is the science of studying and improving relationships between ecological processes in the environment and particular ecosystems. This is done within a variety of landscape scales, development spatial patterns, and organizational levels of research and policy. Concisely, landscape ecology can be described as the science of "landscape diversity" as the synergetic result of biodiversity and geodiversity.

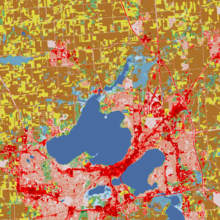

As a highly interdisciplinary field in systems science, landscape ecology integrates biophysical and analytical approaches with humanistic and holistic perspectives across the natural sciences and social sciences. Landscapes are spatially heterogeneous geographic areas characterized by diverse interacting patches or ecosystems, ranging from relatively natural terrestrial and aquatic systems such as forests, grasslands, and lakes to human-dominated environments including agricultural and urban settings.

The most salient characteristics of landscape ecology are its emphasis on the relationship among pattern, process and scale, and its focus on broad-scale ecological and environmental issues. These necessitate the coupling between biophysical and socioeconomic sciences. Key research topics in landscape ecology include ecological flows in landscape mosaics, land use and land cover change, scaling, relating landscape pattern analysis with ecological processes, and landscape conservation and sustainability. Landscape ecology also studies the role of human impacts on landscape diversity in the development and spreading of new human pathogens that could trigger epidemics.

Terminology

The German term Landschaftsökologie–thus landscape ecology–was coined by German geographer Carl Troll in 1939. He developed this terminology and many early concepts of landscape ecology as part of his early work, which consisted of applying aerial photograph interpretation to studies of interactions between environment and vegetation.

Explanation

Heterogeneity is the measure of how parts of a landscape differ from one another. Landscape ecology looks at how this spatial structure affects organism abundance at the landscape level, as well as the behavior and functioning of the landscape as a whole. This includes studying the influence of pattern, or the internal order of a landscape, on process, or the continuous operation of functions of organisms. Landscape ecology also includes geomorphology as applied to the design and architecture of landscapes. Geomorphology is the study of how geological formations are responsible for the structure of a landscape.

History

Evolution of theory

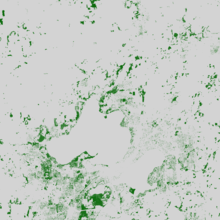

One central landscape ecology theory originated from MacArthur & Wilson's The Theory of Island Biogeography. This work considered the biodiversity on islands as the result of competing forces of colonization from a mainland stock and stochastic extinction. The concepts of island biogeography were generalized from physical islands to abstract patches of habitat by Levins' metapopulation model (which can be applied e.g. to forest islands in the agricultural landscape). This generalization spurred the growth of landscape ecology by providing conservation biologists a new tool to assess how habitat fragmentation affects population viability. Recent growth of landscape ecology owes much to the development of geographic information systems (GIS) and the availability of large-extent habitat data (e.g. remotely sensed datasets).

Development as a discipline

Landscape ecology developed in Europe from historical planning on human-dominated landscapes. Concepts from general ecology theory were integrated in North America. While general ecology theory and its sub-disciplines focused on the study of more homogenous, discrete community units organized in a hierarchical structure (typically as ecosystems, populations, species, and communities), landscape ecology built upon heterogeneity in space and time. It frequently included human-caused landscape changes in theory and application of concepts.

By 1980, landscape ecology was a discrete, established discipline. It was marked by the organization of the International Association for Landscape Ecology (IALE) in 1982. Landmark book publications defined the scope and goals of the discipline, including Naveh and Lieberman and Forman and Godron. Forman wrote that although study of "the ecology of spatial configuration at the human scale" was barely a decade old, there was strong potential for theory development and application of the conceptual framework.

Today, theory and application of landscape ecology continues to develop through a need for innovative applications in a changing landscape and environment. Landscape ecology relies on advanced technologies such as remote sensing, GIS, and models. There has been associated development of powerful quantitative methods to examine the interactions of patterns and processes. An example would be determining the amount of carbon present in the soil based on landform over a landscape, derived from GIS maps, vegetation types, and rainfall data for a region. Remote sensing work has been used to extend landscape ecology to the field of predictive vegetation mapping, for instance by Janet Franklin.

Definitions/conceptions of landscape ecology

Nowadays, at least six different conceptions of landscape ecology can be identified: one group tending toward the more disciplinary concept of ecology (subdiscipline of biology; in conceptions 2, 3, and 4) and another group—characterized by the interdisciplinary study of relations between human societies and their environment—inclined toward the integrated view of geography (in conceptions 1, 5, and 6):

- Interdisciplinary analysis of subjectively defined landscape units (e.g. Neef School): Landscapes are defined in terms of uniformity in land use. Landscape ecology explores the landscape's natural potential in terms of functional utility for human societies. To analyse this potential, it is necessary to draw on several natural sciences.

- Topological ecology at the landscape scale 'Landscape' is defined as a heterogeneous land area composed of a cluster of interacting ecosystems (woods, meadows, marshes, villages, etc.) that is repeated in similar form throughout. It is explicitly stated that landscapes are areas at a kilometres wide human scale of perception, modification, etc. Landscape ecology describes and explains the landscapes' characteristic patterns of ecosystems and investigates the flux of energy, mineral nutrients, and species among their component ecosystems, providing important knowledge for addressing land-use issues.

- Organism-centered, multi-scale topological ecology (e.g. John A. Wiens): Explicitly rejecting views expounded by Troll, Zonneveld, Naveh, Forman & Godron, etc., landscape and landscape ecology are defined independently of human perceptions, interests, and modifications of nature. 'Landscape' is defined – regardless of scale – as the 'template' on which spatial patterns influence ecological processes. Not humans, but rather the respective species being studied is the point of reference for what constitutes a landscape.

- Topological ecology at the landscape level of biological organisation (e.g. Urban et al.): On the basis of ecological hierarchy theory, it is presupposed that nature is working at multiple scales and has different levels of organisation which are part of a rate-structured, nested hierarchy. Specifically, it is claimed that, above the ecosystem level, a landscape level exists which is generated and identifiable by high interaction intensity between ecosystems, a specific interaction frequency and, typically, a corresponding spatial scale. Landscape ecology is defined as ecology that focuses on the influence exerted by spatial and temporal patterns on the organisation of, and interaction among, functionally integrated multispecies ecosystems.

- Analysis of social-ecological systems using the natural and social sciences and humanities (e.g. Leser; Naveh; Zonneveld): Landscape ecology is defined as an interdisciplinary super-science that explores the relationship between human societies and their specific environment, making use of not only various natural sciences, but also social sciences and humanities. This conception is grounded in the assumption that social systems are linked to their specific ambient ecological system in such a way that both systems together form a co-evolutionary, self-organising unity called 'landscape'. Societies' cultural, social and economic dimensions are regarded as an integral part of the global ecological hierarchy, and landscapes are claimed to be the manifest systems of the 'total human ecosystem' (Naveh) which encompasses both the physical ('geospheric') and mental ('noospheric') spheres.

- Ecology guided by cultural meanings of lifeworldly landscapes (frequently pursued in practice but not defined, but see, e.g., Hard; Trepl): Landscape ecology is defined as ecology that is guided by an external aim, namely, to maintain and develop lifeworldly landscapes. It provides the ecological knowledge necessary to achieve these goals. It investigates how to sustain and develop those populations and ecosystems which (i) are the material 'vehicles' of lifeworldly, aesthetic and symbolic landscapes and, at the same time, (ii) meet societies' functional requirements, including provisioning, regulating, and supporting ecosystem services. Thus landscape ecology is concerned mainly with the populations and ecosystems which have resulted from traditional, regionally specific forms of land use.

Relationship to ecological theory

Some research programmes of landscape ecology theory, namely those standing in the European tradition, may be slightly outside of the "classical and preferred domain of scientific disciplines" because of the large, heterogeneous areas of study. However, general ecology theory is central to landscape ecology theory in many aspects. Landscape ecology consists of four main principles: the development and dynamics of spatial heterogeneity, interactions and exchanges across heterogeneous landscapes, influences of spatial heterogeneity on biotic and abiotic processes, and the management of spatial heterogeneity. The main difference from traditional ecological studies, which frequently assume that systems are spatially homogenous, is the consideration of spatial patterns.

Important terms

Landscape ecology not only created new terms, but also incorporated existing ecological terms in new ways. Many of the terms used in landscape ecology are as interconnected and interrelated as the discipline itself.

Landscape

Certainly, 'landscape' is a central concept in landscape ecology. It is, however, defined in quite different ways. For example: Carl Troll conceives of landscape not as a mental construct but as an objectively given 'organic entity', a harmonic individuum of space. Ernst Neef defines landscapes as sections within the uninterrupted earth-wide interconnection of geofactors which are defined as such on the basis of their uniformity in terms of a specific land use, and are thus defined in an anthropocentric and relativistic way. According to Richard Forman and Michel Godron, a landscape is a heterogeneous land area composed of a cluster of interacting ecosystems that is repeated in similar form throughout, whereby they list woods, meadows, marshes and villages as examples of a landscape's ecosystems, and state that a landscape is an area at least a few kilometres wide. John A. Wiens opposes the traditional view expounded by Carl Troll, Isaak S. Zonneveld, Zev Naveh, Richard T. T. Forman/Michel Godron and others that landscapes are arenas in which humans interact with their environments on a kilometre-wide scale; instead, he defines 'landscape'—regardless of scale—as "the template on which spatial patterns influence ecological processes". Some define 'landscape' as an area containing two or more ecosystems in close proximity.

Scale and heterogeneity (incorporating composition, structure, and function)

A main concept in landscape ecology is scale. Scale represents the real world as translated onto a map, relating distance on a map image and the corresponding distance on earth. Scale is also the spatial or temporal measure of an object or a process, or amount of spatial resolution. Components of scale include composition, structure, and function, which are all important ecological concepts. Applied to landscape ecology, composition refers to the number of patch types (see below) represented on a landscape and their relative abundance. For example, the amount of forest or wetland, the length of forest edge, or the density of roads can be aspects of landscape composition. Structure is determined by the composition, the configuration, and the proportion of different patches across the landscape, while function refers to how each element in the landscape interacts based on its life cycle events. Pattern is the term for the contents and internal order of a heterogeneous area of land.

A landscape with structure and pattern implies that it has spatial heterogeneity, or the uneven distribution of objects across the landscape. Heterogeneity is a key element of landscape ecology that separates this discipline from other branches of ecology. Landscape heterogeneity is able to quantify with agent-based methods as well.

Patch and mosaic

Patch, a term fundamental to landscape ecology, is defined as a relatively homogeneous area that differs from its surroundings. Patches are the basic unit of the landscape that change and fluctuate, a process called patch dynamics. Patches have a definite shape and spatial configuration, and can be described compositionally by internal variables such as number of trees, number of tree species, height of trees, or other similar measurements.

Matrix is the "background ecological system" of a landscape with a high degree of connectivity. Connectivity is the measure of how connected or spatially continuous a corridor, network, or matrix is. For example, a forested landscape (matrix) with fewer gaps in forest cover (open patches) will have higher connectivity. Corridors have important functions as strips of a particular type of landscape differing from adjacent land on both sides. A network is an interconnected system of corridors while mosaic describes the pattern of patches, corridors, and matrix that form a landscape in its entirety.

Boundary and edge

Landscape patches have a boundary between them which can be defined or fuzzy. The zone composed of the edges of adjacent ecosystems is the boundary. Edge means the portion of an ecosystem near its perimeter, where influences of the adjacent patches can cause an environmental difference between the interior of the patch and its edge. This edge effect includes a distinctive species composition or abundance. For example, when a landscape is a mosaic of perceptibly different types, such as a forest adjacent to a grassland, the edge is the location where the two types adjoin. In a continuous landscape, such as a forest giving way to open woodland, the exact edge location is fuzzy and is sometimes determined by a local gradient exceeding a threshold, such as the point where the tree cover falls below thirty-five percent.

Ecotones, ecoclines, and ecotopes

A type of boundary is the ecotone, or the transitional zone between two communities. Ecotones can arise naturally, such as a lakeshore, or can be human-created, such as a cleared agricultural field from a forest. The ecotonal community retains characteristics of each bordering community and often contains species not found in the adjacent communities. Classic examples of ecotones include fencerows, forest to marshlands transitions, forest to grassland transitions, or land-water interfaces such as riparian zones in forests. Characteristics of ecotones include vegetational sharpness, physiognomic change, occurrence of a spatial community mosaic, many exotic species, ecotonal species, spatial mass effect, and species richness higher or lower than either side of the ecotone.

An ecocline is another type of landscape boundary, but it is a gradual and continuous change in environmental conditions of an ecosystem or community. Ecoclines help explain the distribution and diversity of organisms within a landscape because certain organisms survive better under certain conditions, which change along the ecocline. They contain heterogeneous communities which are considered more environmentally stable than those of ecotones. An ecotope is a spatial term representing the smallest ecologically distinct unit in mapping and classification of landscapes. Relatively homogeneous, they are spatially explicit landscape units used to stratify landscapes into ecologically distinct features. They are useful for the measurement and mapping of landscape structure, function, and change over time, and to examine the effects of disturbance and fragmentation.

Disturbance and fragmentation

Disturbance is an event that significantly alters the pattern of variation in the structure or function of a system. Fragmentation is the breaking up of a habitat, ecosystem, or land-use type into smaller parcels. Disturbance is generally considered a natural process. Fragmentation causes land transformation, an important process in landscapes as development occurs.

An important consequence of repeated, random clearing (whether by natural disturbance or human activity) is that contiguous cover can break down into isolated patches. This happens when the area cleared exceeds a critical level, which means that landscapes exhibit two phases: connected and disconnected.

Theory

Landscape ecology theory stresses the role of human impacts on landscape structures and functions. It also proposes ways for restoring degraded landscapes. Landscape ecology explicitly includes humans as entities that cause functional changes on the landscape. Landscape ecology theory includes the landscape stability principle, which emphasizes the importance of landscape structural heterogeneity in developing resistance to disturbances, recovery from disturbances, and promoting total system stability. This principle is a major contribution to general ecological theories which highlight the importance of relationships among the various components of the landscape.

Integrity of landscape components helps maintain resistance to external threats, including development and land transformation by human activity. Analysis of land use change has included a strongly geographical approach which has led to the acceptance of the idea of multifunctional properties of landscapes. There are still calls for a more unified theory of landscape ecology due to differences in professional opinion among ecologists and its interdisciplinary approach (Bastian 2001).

An important related theory is hierarchy theory, which refers to how systems of discrete functional elements operate when linked at two or more scales. For example, a forested landscape might be hierarchically composed of drainage basins, which in turn are composed of local ecosystems, which are in turn composed of individual trees and gaps. Recent theoretical developments in landscape ecology have emphasized the relationship between pattern and process, as well as the effect that changes in spatial scale has on the potential to extrapolate information across scales. Several studies suggest that the landscape has critical thresholds at which ecological processes will show dramatic changes, such as the complete transformation of a landscape by an invasive species due to small changes in temperature characteristics which favor the invasive's habitat requirements.

Application

Research directions

Developments in landscape ecology illustrate the important relationships between spatial patterns and ecological processes. These developments incorporate quantitative methods that link spatial patterns and ecological processes at broad spatial and temporal scales. This linkage of time, space, and environmental change can assist managers in applying plans to solve environmental problems. The increased attention in recent years on spatial dynamics has highlighted the need for new quantitative methods that can analyze patterns, determine the importance of spatially explicit processes, and develop reliable models. Multivariate analysis techniques are frequently used to examine landscape level vegetation patterns. Studies use statistical techniques, such as cluster analysis, canonical correspondence analysis (CCA), or detrended correspondence analysis (DCA), for classifying vegetation. Gradient analysis is another way to determine the vegetation structure across a landscape or to help delineate critical wetland habitat for conservation or mitigation purposes (Choesin and Boerner 2002).

Climate change is another major component in structuring current research in landscape ecology. Ecotones, as a basic unit in landscape studies, may have significance for management under climate change scenarios, since change effects are likely to be seen at ecotones first because of the unstable nature of a fringe habitat. Research in northern regions has examined landscape ecological processes, such as the accumulation of snow, melting, freeze-thaw action, percolation, soil moisture variation, and temperature regimes through long-term measurements in Norway. The study analyzes gradients across space and time between ecosystems of the central high mountains to determine relationships between distribution patterns of animals in their environment. Looking at where animals live, and how vegetation shifts over time, may provide insight into changes in snow and ice over long periods of time across the landscape as a whole.

Other landscape-scale studies maintain that human impact is likely the main determinant of landscape pattern over much of the globe. Landscapes may become substitutes for biodiversity measures because plant and animal composition differs between samples taken from sites within different landscape categories. Taxa, or different species, can “leak” from one habitat into another, which has implications for landscape ecology. As human land use practices expand and continue to increase the proportion of edges in landscapes, the effects of this leakage across edges on assemblage integrity may become more significant in conservation. This is because taxa may be conserved across landscape levels, if not at local levels.

Land change modeling

Land change modeling is an application of landscape ecology designed to predict future changes in land use. Land change models are used in urban planning, geography, GIS, and other disciplines to gain a clear understanding of the course of a landscape. In recent years, much of the Earth's land cover has changed rapidly, whether from deforestation or the expansion of urban areas.

Relationship to other disciplines

Landscape ecology has been incorporated into a variety of ecological subdisciplines. For example, it is closely linked to land change science, the interdisciplinary of land use and land cover change and their effects on surrounding ecology. Another recent development has been the more explicit consideration of spatial concepts and principles applied to the study of lakes, streams, and wetlands in the field of landscape limnology. Seascape ecology is a marine and coastal application of landscape ecology. In addition, landscape ecology has important links to application-oriented disciplines such as agriculture and forestry. In agriculture, landscape ecology has introduced new options for the management of environmental threats brought about by the intensification of agricultural practices. Agriculture has always been a strong human impact on ecosystems.

In forestry, from structuring stands for fuelwood and timber to ordering stands across landscapes to enhance aesthetics, consumer needs have affected conservation and use of forested landscapes. Landscape forestry provides methods, concepts, and analytic procedures for landscape forestry. Landscape ecology has been cited as a contributor to the development of fisheries biology as a distinct biological science discipline, and is frequently incorporated in study design for wetland delineation in hydrology. It has helped shape integrated landscape management. Lastly, landscape ecology has been very influential for progressing sustainability science and sustainable development planning. For example, a recent study assessed sustainable urbanization across Europe using evaluation indices, country-landscapes, and landscape ecology tools and methods.

Landscape ecology has also been combined with population genetics to form the field of landscape genetics, which addresses how landscape features influence the population structure and gene flow of plant and animal populations across space and time and on how the quality of intervening landscape, known as "matrix," influences spatial variation. After the term was coined in 2003, the field of landscape genetics had expanded to over 655 studies by 2010, and continues to grow today. As genetic data has become more readily accessible, it is increasingly being used by ecologists to answer novel evolutionary and ecological questions, many with regard to how landscapes effect evolutionary processes, especially in human-modified landscapes, which are experiencing biodiversity loss.